©

2004 Jeff Matthews & napoli.com

San Carlo

Theater (1)

San Carlo Theater in Naples has always had a reputation

for sounding good. It was built back when the only rule for architects

was, "Imitate the construction of halls that sound good." Not very scientific,

but it worked. Thus, it was with some trepidation that concert-goers

at San Carlo awaited the downbeat of Orff's Carmina Burana

in April 1992 on the occasion of the reopening of the newly renovated

theater. A collective sigh of relief went up (heard quite clearly even

in the back row!): things sounded better than ever, according to Roberto

de Simone, noted Neapolitan musicologist and composer. It is just

one more chapter in the history of Naples' most famous theater. San Carlo Theater in Naples has always had a reputation

for sounding good. It was built back when the only rule for architects

was, "Imitate the construction of halls that sound good." Not very scientific,

but it worked. Thus, it was with some trepidation that concert-goers

at San Carlo awaited the downbeat of Orff's Carmina Burana

in April 1992 on the occasion of the reopening of the newly renovated

theater. A collective sigh of relief went up (heard quite clearly even

in the back row!): things sounded better than ever, according to Roberto

de Simone, noted Neapolitan musicologist and composer. It is just

one more chapter in the history of Naples' most famous theater.

Today,

of course, most people, if asked to name the opera house in Italy,

say La Scala in Milan. That is true, but only because times have changed

dramatically since the mid–1700s when Naples, in general, and

San Carlo, in particular, were jewels in the crown of European culture.

Naples was home to some of the great names in Western music, such as

Alessandro Scarlatti and Giovanni

Battista Pergolesi. The city was also the birthplace of the best-loved

form of operatic entertainment in the 18th century, the Comic

Opera.

San Carlo

was built by the Bourbon king, Charles III,

and takes its name from the fact that it opened on November 4, 1737,

the feast day of the saint the king was named for. The king, of course,

was present on opening night to see and hear Achille in Sciro,

with music by the Neapolitan Domenico Sarro, who is now largely forgotten;

the libretto was by Pietro Metastasio, the great court poet to the Emperor

of Austria and to this day considered a giant among librettists.

The festive

cantata which preceded the first opera at San Carlo sang the praises

of the new theater: "Behold the new, sublime, spacious theater, vaster

than that which Europe hath seen." A few years later, the English music

historian Charles Burney said that San Carlo "as a spectacle surpasses

all that poetry or romance have painted."

Among the

best known Neapolitan composers of the 18th century were Pergolesi

(1710-1736), Domenico Cimarosa (1749-1801)

and Giovanni Paisiello (1740-1816), all

masters of the comic opera, light-hearted fluff which featured

lots of fat old lechers rolling their eyes while they laughed and chased

virgins around the stage. The names of a few of the works let you know

just what you're in for: The Servant Mistress, The Clandestine

Marriage, The Enamoured Monk. Comic operas started out in

the early 1700s as short interludes between the acts of serious works

with Greek names, usually Achilles or Opheus or one of their relatives,

names that show just how seriously composers still took the Renaissance

commitment to revive classical ideals. Much of this music, appropriately

called opera seria, was as dull as cereal; so, enter the rollicking

street farces that were to develop into comic opera. [A separate article

on Monteverdi and the beginnings of opera may be read by

clicking here.]

The

Servant Mistress was the first full-scale comic opera and was first

performed in 1731 at the San Bartolomeo

Theater in Naples, the house that San Carlo replaced. It is still played

today and is one of the very few Neapolitan comic operas still in the

standard repertoire. Hundreds were written and almost none survive.

They were done in by Romanticism. Fluff was fun, but by the late 18th

century, it had given way to more serious things such as Revolution,

Heroism, Love, Courage, Valor and Beethoven. Neapolitan comic operas,

also, it is fair to say, suffer somewhat in comparison to the comic

operas of Mozart. It is also fair to say, however, that most things

suffer somewhat in comparison to Mozart. The

Servant Mistress was the first full-scale comic opera and was first

performed in 1731 at the San Bartolomeo

Theater in Naples, the house that San Carlo replaced. It is still played

today and is one of the very few Neapolitan comic operas still in the

standard repertoire. Hundreds were written and almost none survive.

They were done in by Romanticism. Fluff was fun, but by the late 18th

century, it had given way to more serious things such as Revolution,

Heroism, Love, Courage, Valor and Beethoven. Neapolitan comic operas,

also, it is fair to say, suffer somewhat in comparison to the comic

operas of Mozart. It is also fair to say, however, that most things

suffer somewhat in comparison to Mozart.

Recently,

Naples held a months-long revival of the music of Pergolesi, many of

whose works have not been heard since they were first performed. Like

many of his contemporaries, he was a very versatile composer; his best

known composition, one which is still very much part of the standard

orchestral repertoire today is a serious, sacred work: the Stabat

Mater.

Another

great composer of comic opera was Gioacchino Rossini (1792-1868). He was not Neapolitan,

but is intimately connected with the musical history of the city, in

that he took over the role of "house composer" in 1814. It was

the beginning of the move away from Neapolitan composers, but one that

kept San Carlo in the mainstream of European music, at least for a while

longer. Rossini, Vincenzo Bellini and Gaetano

Donizetti, three of the great names in Italian opera in the first

half of the 19th century, were all connected with the

Naples conservatory and San Carlo. Bellini and Donizetti were the

bridge to the new music of Romanticism, while Rossini was, somewhat

anachronistically, the link to the comic operas of the past. He deserved

better than he got.

Rossini's

greatest work, The Barber of Seville, is arguably the best comic

opera ever composed, Mozart notwithstanding. It was performed

for the first time in Rome and not in Naples. That may have been a good

thing, since there was already a very popular work of the same name

by the Neapolitan, Paisiello, whose hooligan fans went to Rome for the

opening of Rossini's work just to make rude noises. They say that even

members of the cast(!) conspired to make the premiere flop. The conspiracy

worked so well that Rossini got discouraged and didn't go to the second

performance; his friends had to hunt him up and tell him it had been

a hit. History, of course, has since consigned Paisiello's work to the

list of operatic also-rans. Rossini didn't take criticism or failure

lightly. His attempt at something a little more serious and in keeping

with the times, William Tell, was not well received and he subsequently

quit writing opera altogether at the age of 37. He lived another thirty

years.

San Carlo

burned to the ground during a performance of one of Rossini's works

in 1816, but was rebuilt in a few months time. It was even more spectacular

than the original. Stendahl wrote that he felt as if he had been "transported

to the palace of some oriental emperor…my eyes were dazzled, my

soul enraptured. There is nothing in the whole of Europe to compare

with it."

By 1850,

a northern Italian composer had appeared on the scene: Giuseppe Verdi.

In spite of the prestige of the Naples theater, the unfavorable conditions

of censorship in the Kingdom of Naples at least partially contributed

to Verdi's decision to take his operas elsewhere, particularly after

Neapolitan censors objected to the regicidal

theme of Un Ballo in Maschera.

Even after the unification of Italy,

when censorship was no longer a problem in Naples, Italy's greatest

composer still regarded Naples and San Carlo as a provincial backwater.

By the

late 19th century, the emphasis in opera in Italy had for political

and economic reasons shifted to the north. San Carlo was late in introducing

the new music of the day, works by Gounod, Bizet, and Wagner, for example.

Neapolitan composers such as Leoncavallo (I Pagliacci) and Alfano

(most famous for having finished Puccini's last work, Turandot

) went elsewhere to live and work. Arturo Toscanini took over the direction

of La Scala in Milan in 1899 and assured that city's supremacy in the

world of opera.

San Carlo

has since continued to go its own peculiar way. In 1901, a young Neapolitan,

Enrico Caruso, sang the role of Nemorino

in Donizetti's L'elisir d'amore. If you go to Caruso's

house in Naples today and see that it has become something of

a shrine, you might well forget that the voice subsequently judged the

greatest operatic tenor in history didn't go over well with the hometown

crowd. He got a bad review in the papers

and vowed never to sing in Naples again. He kept his promise. He went

to America and became one of the 'tired, poor, and huddled masses,

yearning' —to record for RCA.

San Carlo

has recently undergone an overhaul like none in its history. There

are new electrical systems, new public lifts and stage elevators, extensive

fireproof reupholstering and smoke detectors with spray extinguishers.

Thus, new life has been granted to a venerable institution. It is not

common, you know, to find places of culture, such as San Carlo, in continuous

operation for two-and-a-half centuries, anymore than it is common to

find large centers of population, such as Naples, continuously inhabited

for two-and-a-half millennia. Perhaps it is fitting that one is home

to the other.

[More

on San Carlo click here.]

Mergellina;

Sannazzaro, J.; Ravaschieri di Satriano (palazzo)

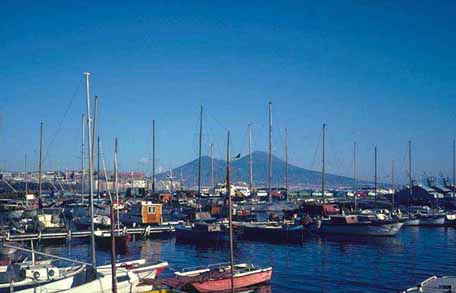

Mergellina is the "other" port in Naples. It is at the

west end of via Caracciolo before the coast starts its long curve

out to Posillipo. Once, Mergellina was a quaint fishing village and

the subject of folksong and myth. Today, it has developed as an important

harbor for pleasure and tourist boats, including those that make runs

to Capri and, indeed, to all of the small secondary

ports in the Campania region, from Bacoli at the extreme top end of

the Bay of Naples to Sapri, many hours to the south. It is, however,

still a working port for fishermen. Mergellina is the "other" port in Naples. It is at the

west end of via Caracciolo before the coast starts its long curve

out to Posillipo. Once, Mergellina was a quaint fishing village and

the subject of folksong and myth. Today, it has developed as an important

harbor for pleasure and tourist boats, including those that make runs

to Capri and, indeed, to all of the small secondary

ports in the Campania region, from Bacoli at the extreme top end of

the Bay of Naples to Sapri, many hours to the south. It is, however,

still a working port for fishermen.

It is not

immediately evident from studying the modern lay-out of the coast between

the Castel dell'Ovo and the harbor of

Mergellina just how isolated Mergellina was from the rest of Naples

through a long history that stretches from the days of the Greeks to

the present. It is true that the city of Naples, itself—the historic center and the immediate surroundings—is

the oldest continuously inhabited center of large population in Europe.

It is, however, equally true that many of the names that one associates

with Naples, such as Mergellina (and even Santa Lucia, much closer in

towards the city than Mergellina) were, until the 1500s, "quaint fishing

villages on the outskirts of Naples" (and I copied that phrase from

an early tour-guide to the area, which so described Santa Lucia, the

area around the Castel dell'Ovo).

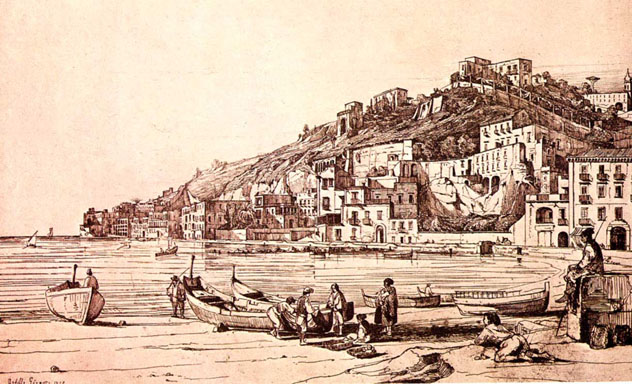

Mergellina

is yet another mile to the west along the waterfront. Today, Santa Lucia

and Mergellina are connected by via Caracciolo, a road from the late

1800s. (See here for an item on the urban

renewal of Naples at that time.) If, in the mind's eye, you strip that

road away, you have the modern Public Gardens, the Villa Comunale, which

can still be said to connect the two ends of the long stretch of waterfront

between Santa Lucia and Mergellina. Those gardens were built in the

1780s. Before that park was put in place on reclaimed land, the whole

stretch was a beachfront with water rolling up approximately to where

the road, Riviera di Chiaia, now runs along the inside of the

gardens, 100 yards from the modern seafront.

And that road, Riviera di Chiaia, was

laid in the1600s to accommodate the new and exclusive Spanish mansions

that were wending their way ever to the west towards Mergellina.

The first villa—at the east end of the Villa Comunale,

still a mile from Mergellina—was the Palazzo Ravaschieri di

Satriano, a building from 1605 (photo, left). It was prime beachfront

property 400 years ago. (Much later, Goethe mentions the building with

fondness in his Italian Journeys. He speaks of a lovely and enigmatic

woman. He discreetly avoids detailing his notorious womanizing but he

is probably talking about donna Teresa Filangieri, the wife of Filippo

Ravaschieri, owner of the villa at the time. In this photo—on

the hill in the background—Castel Sant'Elmo

is seen on the left and the museum of San

Martino on the right.) Drawings of the area from the 1680s show

a lovely coast-line with a long string of villas starting at this mansion

and a single long road, Riviera di Chiaia, lined with trees. That was

how one got to Mergellina from Naples in the 1600s. And that road, Riviera di Chiaia, was

laid in the1600s to accommodate the new and exclusive Spanish mansions

that were wending their way ever to the west towards Mergellina.

The first villa—at the east end of the Villa Comunale,

still a mile from Mergellina—was the Palazzo Ravaschieri di

Satriano, a building from 1605 (photo, left). It was prime beachfront

property 400 years ago. (Much later, Goethe mentions the building with

fondness in his Italian Journeys. He speaks of a lovely and enigmatic

woman. He discreetly avoids detailing his notorious womanizing but he

is probably talking about donna Teresa Filangieri, the wife of Filippo

Ravaschieri, owner of the villa at the time. In this photo—on

the hill in the background—Castel Sant'Elmo

is seen on the left and the museum of San

Martino on the right.) Drawings of the area from the 1680s show

a lovely coast-line with a long string of villas starting at this mansion

and a single long road, Riviera di Chiaia, lined with trees. That was

how one got to Mergellina from Naples in the 1600s.

Mergellina, itself—before

that date—was pretty much isolated, except by sea and a single

road leading down from the Posillipo height directly above, a twisting

and steep affair called the Rampe di San Antonio. That road comes out near the

modern Mergellina train station. In the days before trains, all you

saw when you got to the bottom was the Roman tunnel (still in use in

those days) called the "Neapolitan Crypt", in the area called Piedigrotta,

the homonymous church being one of the most famous in Neapolitan tradition.

The modern road, via Posillipo, that leads from Mergellina west

to the very end of the Posillipo hill was not completed until the French

rule of Naples under Murat, although the

Spanish did build a short stretch in that direction to get from Mergellina

to Villa Donn'Anna. Mergellina, itself—before

that date—was pretty much isolated, except by sea and a single

road leading down from the Posillipo height directly above, a twisting

and steep affair called the Rampe di San Antonio. That road comes out near the

modern Mergellina train station. In the days before trains, all you

saw when you got to the bottom was the Roman tunnel (still in use in

those days) called the "Neapolitan Crypt", in the area called Piedigrotta,

the homonymous church being one of the most famous in Neapolitan tradition.

The modern road, via Posillipo, that leads from Mergellina west

to the very end of the Posillipo hill was not completed until the French

rule of Naples under Murat, although the

Spanish did build a short stretch in that direction to get from Mergellina

to Villa Donn'Anna.

The

Spanish, then, are the ones who started the development that would eventually

incorporate Mergellina into "greater Naples". That development was continued

under the short, but productive, period of the Austrian

vicerealm and then, of course, the Bourbons. The

Spanish, then, are the ones who started the development that would eventually

incorporate Mergellina into "greater Naples". That development was continued

under the short, but productive, period of the Austrian

vicerealm and then, of course, the Bourbons.

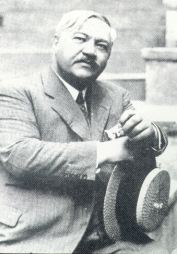

Mergellina's

favorite son is, no doubt, the poet Jacopo Sannazaro (1458-1539) (painting,

left), whose verses in Italian are part of the body of literature that

helped form that language in the Middle Ages. His Latin works, primarily

De partu Virginis, though little read today, earned him the nick-name

of "the Christian Virgil". A main square, one block from the harbor,

is named for him.

Filangieri,

Gaetano (1752—1788)

The man who wrote the US Constitution?

It

is certainly an overstatement that the Constitution of the United States

of America was written in a beautiful old building—still

called "the castle"—in Vico Equense, a small town on the

Bay of Naples about halfway out the Sorrentine peninsula, but that's

what citizens of that hamlet delight in telling visitors. Viewed charitably,

it's a good story—a very human one with just that kernel

of historical fact that piques one's interest. It also provides a small

introduction to the person of Gaetano Filangieri, a leading figure of

the Neapolitan Enlightenment, a philosophical movement that thrived

in the mid-and late 18th century.

Filangieri

was born in Naples in 1752. He gained early favor at the court of the

Bourbon monarch, Charles III, King of Naples,

by virtue of his Political Reflections, in which he defended

the king's enlightened reforms of the legal system. He is best remembered

today, however, for his La Scienza della legislazione (The Science

of Legislation) a work he started in 1780 and planned as seven volumes

but which remained unfinished in the middle of the fifth volume upon

his death in 1788.

The

Science of Legislation was, in short, a recipe for creating a just

society based on reason. It ranged from rules on how laws should

be formulated to economics to education and societal ethics. This remarkable

work was an outgrowth of the French enlightenment and was inspired by

the principle that reason should be at the core of a just legal system,

and that the measure of the just society was how well it dealt with

the social and economic realities of that society. It pinpointed the

societal split between the landed few who had much and the landless

many who had nothing—a potentially ruinous situation for modern

nations, which had to face increasing population, inefficient agricultural

output and the beginnings of industry.

Filangieri

may not have been the John the Baptist of class warfare that later Marxists

like to claim, but he was a formidable advocate of reform, calling for

a large class of small property owners, universal public education and

equality before the law. He wanted unlimited free trade and the abolition

of medieval institutions, which impeded production and national

well-being. He called for freedom of the press and toleration in juridical

and social matters, ideas that would later mark the age of post-absolutist

Europe. These ideas certainly had their philosophical origin in the

French Enlightenment but they remained in that lofty arena of philosophical

debate until Filangieri wrote down the specifics—how they

laws themselves would actually look on paper. The Science of

Legislation was a masterpiece of the Italian Enlightenment—and

in 1784 also put on the Index, the Roman Catholic Church's list

of banned books.

The

Science of Legislation enjoyed an immediate success and was translated

into other European languages almost immediately. Though the tone of

the entire work was one of reasoned reform and not violent revolution,

it was on the must-read list of the Jacobins as they prepared the French

Revolution of 1789; also, it was an inspiration to the later Neapolitan Revolution of 1799.

Filangieri's

view of events in the New World, specifically, the American Revolution,

underwent some interesting changes. Like many Europeans, he saw America

from a colonizer's point of view. In The Science of Legislation he

frequently refers to the entire western hemisphere—all

of the Americas—as "Europe's farm". His main concern for

social equality and justice in the Americas seems to have been a pragmatic

one; this is, if Europe abused her colonies in the New World, they might

rebel, fall away and become independent, depriving Europe of a great

resource. Thus, good government was good for everyone—fair

to the governed and profitable to those who govern.

He expressed

those views in 1780 when the first part of The Science of Legislation

was published and General Washington's forces had not yet spent their

rough winter at Valley Forge. Yet, one year later, the American revolution

was over and Filangieri—like many other children of the French

Enlightenment—fell under the spell of the "American myth,"

a place where "Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness" had just

swept the day. The French historian, J.J. Godechot, has written:

| The

American revolution had immense repercussions in Europe. First

of all, it gave to Europeans the impression that they were living

in an age that was on the verge of prodigious change. They

saw that the philosophical destinies they had been discussing

were not utopian, but might even be fulfilled immediately. That

revolution created for Europe the 'American Myth', the image of

a new society close to the one described by Rousseau.

[J.J.

Godechot, Les révolutions (1770-1799), Paris,

1963. Cited in Andreatta, below. English translation, here,

is mine.]

|

Filangieri

initiated an exchange of letters with Benjamin Franklin, sending him

a copy of the finished portions of The Science of Legislation,

at which point Franklin ordered copies of the remaining volumes as they

would be published. Filangieri also mentioned to Franklin the idea of

emigrating to the new nation and, specifically, to that enlightened

center of the new nation, Philadelphia. From his letter of December

2, 1782, to Franklin:

| Even

as a child, my eyes were drawn to Philadelphia. I have become

so used to viewing it as the only place where I might be happy,

that I can no longer get that idea out of my head. ... But how

can I leave my country? ... Might not my own works on the law

lead you to consider inviting me to help draw up the new legal

code you are preparing for the United Provinces of America? ...

Once I got to America, who could ever convince me to return to

Europe! How could I ever then leave that haven of virtue, that

land of heroes and city of brothers, all to return to a nation

corrupted by vice and degraded by servitude? ... Having known

a society of citizens, could I ever again desire the company of

courtesans and slaves?

[Cited

in both Andreatta and Pace, below. English translation, here,

is mine.]

|

The extent

of the exchange of letters between Filangieri and Franklin is documented

in Antonio Pace's authoritative Benjamin Franklin and Italy (see

bibliography, below.) Because some of that correspondence has not survived,

it is impossible to be precise about all the details. Yet, in the words

of Pace, "...[what has survived] allows us to piece together almost

completely... [the nature of the correspondence]...".

This

1805 engraving of Franklin is by J. Thompson,

after a painting by J.A. Duplessis.

Filangieri

and Franklin exchanged letters from 1782 to 1787. On the one hand, Franklin

was the American Rousseau—scientist, philosopher, elder statesman,

charmer and absolute toast of Paris during his term as US ambassador

to France. On the other hand, Filangieri was the young, enthusiastic

social reformer, eager to flaunt his considerable knowledge and, as

well, just as eager to reap praise from the American, whom he quite

obviously worshipped. Filangieri

and Franklin exchanged letters from 1782 to 1787. On the one hand, Franklin

was the American Rousseau—scientist, philosopher, elder statesman,

charmer and absolute toast of Paris during his term as US ambassador

to France. On the other hand, Filangieri was the young, enthusiastic

social reformer, eager to flaunt his considerable knowledge and, as

well, just as eager to reap praise from the American, whom he quite

obviously worshipped.

After an

exchange of gifts (including copies of The Science of Legislation

for Franklin) and after Filangieri had semi-invited himself to America,

Franklin cautiously discouraged Filangieri from jumping into such a

risky venture without really knowing what he might be getting into.

To that end, Franklin suggested that the young man jockey for position

in whatever diplomatic or economic relations might be about to

open up between the new United States of America and Filangieri's Kingdom

of Naples. Filangieri saw the wisdom of that suggestion and agreed to

look into it. Franklin then sent Filangieri some French translations

of the various constitutions of the individual states in the US. Filangieri

thanked him, commenting that they seemed too restrictive in terms of

allowing the will of the people to flourish!

Filangieri

died of tuberculosis in 1788 at the ridiculously young age of 35. That

was, however, long enough to see the inadequate Articles of Confederation

fail to regulate the new "haven of virtue and land of heroes". And it

was long enough to see his pen-pal, Benjamin Franklin—in

spite of great age and infirmity—head the Pennsylvania

delegation to the hopeful Constitutional Convention of 1787. Franklin

sent Filangieri a copy of a draft of the new Constitution, appending

the note, "...it may be a matter of some curiosity to you, to know what

is doing in this part of the world respecting legislation." It is not

clear whether Filangieri received and read that before his death. After

Filangieri died, his wife sent Franklin a poignant note, relating that

her husband had left her nothing but the "memory of his virtues". Here,

again, we don't know that Franklin got the note before he, himself,

passed away.

Filangieri

did not see the adoption of the Constitution of the United States in

1789. He also missed the cataclysmic French Revolution of

the same year as well as the brief excursion into republicanism

in his own Kingdom of Naples in 1799; thus, whatever his opinions might

or might not have been on these events is speculation. Missing the short-lived

republican overthrow of the Bourbons in 1799 was probably just as well.

He most certainly would have joined the Republic and wound up on the

gallows. More than one Bourbon judge at the royalist trials of the Neapolitan

rebels lamented that Filangieri was no longer around to get what he

deserved.

Well, he

does deserve his reputation as an enlightened reformer.

Did he really have anything to do with the substance of the US Constitution?

I don't know—and that puts me in pretty good company. It

is true that Franklin ordered a lot of copies of everything that Filangieri

wrote, so he was obviously doing something with them besides reading

them, himself—perhaps handing them around to his friends

as they beat themselves up over how to formulate a workable document

that would govern a new nation. (There was no integral English translation

of the Science of Legislation until 1806, but bits and pieces

of it are bound to have been in circulation well before that.) So, if

my friends in Vico Equense want to believe that Gaetano Filangieri burned

the midnight oil in "the castle" turning out drafts of the US Constitution

to pass on to Franklin who then informed the Convention—then,

who am I meddle with a good story?

Worth

reading:

Andreatta,

Alberto. Le Americhe di Gaetano Filangieri. Edizioni Scientifiche

Italiane. Naples. 1995.

Pace,

Antonio. Benjamin Franklin and Italy. Philadelphia, 1958.

San

Gregorio Armeno (1)

via

S. Gregorio Armeno

The

church/monastery of San Gregorio Armeno is in the heart of the historic

center of Naples and has given its name to the street on which it

is situated. In common parlance, that street is referred to as the street

of the figurari, in reference to those who craft the popular

figures and sets used in the typical Neapolitan Christmas manger scene,

the presepe. The street is marked by

the tower of the church belfry that actually spans the street, itself

(see photo). It is from the 1700s and was built onto an earlier walkway

above the street. The

church/monastery of San Gregorio Armeno is in the heart of the historic

center of Naples and has given its name to the street on which it

is situated. In common parlance, that street is referred to as the street

of the figurari, in reference to those who craft the popular

figures and sets used in the typical Neapolitan Christmas manger scene,

the presepe. The street is marked by

the tower of the church belfry that actually spans the street, itself

(see photo). It is from the 1700s and was built onto an earlier walkway

above the street.

The church

was founded shortly after the iconoclast decrees of the eighth century

caused a number of religious orders to flee the Byzantine empire and

seek refuge elsewhere. Those dedicated to Gregory, bishop of Armenia

(257-332), founded their place of worship in Naples on the site of an

older Roman temple of Ceres. In 1025 it was joined with two other

adjacent chapels into a single complex as a Benedectine monastic order.

[For a separate item on early Christian churches in Naples, click

here.]

The

courtyard of San Gregorio Armeno

The monastery

still functions as such, retaining its high walls and maintaining a

spectacular inner courtyard characterized by a central fountain

with a sculpture of Christ and the Samaritan by Matteo

Bottigliero from 1733.

Jesuits

in Naples

I

have read any number of times that the "Jesuits were expelled from Naples

in 1773" and have even referred to that episode in some of the items

I write. It recently occurred to me that I knew nothing about the affair.

So, with apologies to any Jesuit historians who may be reading this…(please

don't hunt me down to "correct" me). I

have read any number of times that the "Jesuits were expelled from Naples

in 1773" and have even referred to that episode in some of the items

I write. It recently occurred to me that I knew nothing about the affair.

So, with apologies to any Jesuit historians who may be reading this…(please

don't hunt me down to "correct" me).

"Jesuits"

are, properly termed, members of "The Society of Jesus"; the name

"Jesuit" was apparently coined by the Protestant, Calvin, although it

is commonly used even today by Roman Catholics. The Society was founded

by a Spanish soldier, Ignatius of Loyola in 1539. He originally called

his order "The Company of Jesus," an indicator, no doubt, of the militant,

aggressive spirit that imbued the organization. Although the Company

was not founded expressly to combat Protestantism (Martin Luther put

his 95 Theses up on the castle church door in Wittenberg in 1517), it

was in the forefront of the movement of Catholic revival commonly called

the "Counter-Reformation," the official origins of which were at the

Council of Trent in 1545. The Jesuits were (and are) extremely active

in missionary activity throughout the word and are known, as well, for

their charitable work and emphasis on education.

From the

very beginning, the order of Jesuits was marked by—I think it

is fair to say—a supranational sense of mission. Their ultimate

religious allegiance was, of course, to the Pope, but they also swore

allegiance to the head of their order, the General, an office that became

so strong in the course of the centuries that its holder was often termed—unofficially,

of course—"The Black Pope". That kind of situation breeds a sense

of, at least, semi-autonomy—guaranteed not to sit well with an

earthly monarch.

In a way,

obedience to God before King made some sense in the Middle Ages, especially

the early Middle Ages, before there were European nation states. There

certainly was a time when you were, first of all, a Christian before

you were Spanish or French or German. Yet, by the 1500s—and certainly

the 1600s—that sense of overarching obedience to the princes of

the Church over the princes of the Earth was an anachronism and was

one of the factors that contributed to the conflict between the Jesuits

and the rulers of Europe, a conflict that led to the eventual suppression

of the order.

By the

mid-1700s, Jesuit activities in the mission field, in commerce, trade

and banking (in order to have money for their missions)—their

behind-the-scene intrigues (according to their critics)—created

such ill feeling between them and, primarily, the Bourbon monarchs of

Europe (France, Naples, Spain) that there was wholesale call from those

nations to the Pope to abolish the order.

Some nations

didn't wait. Portugal took the matter into its own hands in 1760 and

kicked the Jesuits out of the country. France did the same in 1762.

Spain expelled the Jesuits in 1767, marching 6000 of them to the coast

and expelling them to the Papal States. It is clear that the general

spirit of the times also had something to do with all this. The Humanism

of the French Enlightenment was bound to be on a collision course with

a dogmatic religious order. France and the Kingdom of Naples were home

to many influential philosophers who were natural enemies of such soldiers

of the faith as the Jesuits.

Clement

XIII, a friend of the Jesuits, was elected Pope in 1758. When he died

in February 1769, a conclave to elect his successor assembled in Rome.

Those charged with electing the new Pope were beset by a powerful coalition

of anti-Jesuits from Spain, France and Naples whose single purpose was

to get someone elected who would abolish the Jesuit order. Representatives

from those nations were—at least, so they said—prepared

to wage economic, military, and even religious war (that is, they threatened

schism) against the Papal States unless they got what they wanted. Such

intrigues are beyond me, but, interestingly, the choice for Pope went

to one who had been educated by the Jesuits—Cardinal Ganganelli,

who took the papal name of Clement XIV.

Medallion

with a likeness of Clement XIV

The

Pope was reluctant to suppress the Jesuits. He still had some political

backing from the Hapsburgs in Austria, who, obviously, were against

anything the Bourbons were for. That support faded when empress Maria-Theresa

married off one of her children, Marie Antoinette, to the Bourbon king

of France. Part of the agreement was that Habsburg royalty stop defending

the nefarious Jesuits. The

Pope was reluctant to suppress the Jesuits. He still had some political

backing from the Hapsburgs in Austria, who, obviously, were against

anything the Bourbons were for. That support faded when empress Maria-Theresa

married off one of her children, Marie Antoinette, to the Bourbon king

of France. Part of the agreement was that Habsburg royalty stop defending

the nefarious Jesuits.

In any

case, the Pope caved in to the anti-Jesuits and issued a decree of suppression,

the Dominus ac Redemptor, in June 1773. It wasn't a particularly

strong edict. The general line was that orders had been abolished in

the past and since the presence of the Jesuits seemed to be such a source

of conflict, it was better for the peace of the church if the society

was abolished. The strongest language was probably,

| …the

Society from its earliest days bore the germs of dissensions and

jealousies which tore its own members asunder, led them to rise

against other religious orders, against the secular clergy and

the universities, nay even against the sovereigns who had received

them in their states… |

Although

some regimes in northern and eastern Europe refused to implement the

ban, elsewhere the results were immediate. In Naples, Jesuit property

was seized, and their churches closed. (In some cases, they were given

to other orders (the Church of San Ferdinando,

for example), and the Jesuit brothers themselves were expelled from

the Kingdom. Similar to the Spanish experience, Neapolitan Jesuits were

marched north to the border with the Papal States and expelled under

threat of death if they returned.

A

common thread in the expulsion of the Jesuits in Spain and then Naples

is that Charles III of Bourbon was the

King of Spain when the Jesuits were forced to leave that nation, and

his son, Ferdinand IV was the king of Naples when the same thing happened

there. (Charles, of course, had ruled Naples before abdicating to return

to Spain.) Influential in the lives of both monarchs was Bernardo Tanucci

(painting, left), the astute Foreign Minister under Charles III and

then the regent of Charles' child-king son. Tanucci was one of the prime

movers among anti-Jesuits in Naples. His influence faded after that,

and he was edged out of the picture by Ferdinand's ambitious wife, Caroline. A

common thread in the expulsion of the Jesuits in Spain and then Naples

is that Charles III of Bourbon was the

King of Spain when the Jesuits were forced to leave that nation, and

his son, Ferdinand IV was the king of Naples when the same thing happened

there. (Charles, of course, had ruled Naples before abdicating to return

to Spain.) Influential in the lives of both monarchs was Bernardo Tanucci

(painting, left), the astute Foreign Minister under Charles III and

then the regent of Charles' child-king son. Tanucci was one of the prime

movers among anti-Jesuits in Naples. His influence faded after that,

and he was edged out of the picture by Ferdinand's ambitious wife, Caroline.

The Jesuits

didn't return to the Kingdom of Naples until 1827—well after the

initial wave of anti-Jesuit feeling and well after the ultimate anti-cleric,

Napoleon (acting through his puppet-king, Murat),

had caused all monastic orders in Naples to be abolished. The Restoration

of 1815 had its way and the order eventually came back to Naples. In

1860, they were again dispersed as part of the general wave of anti-clericalism

in the new united Italy. In Naples, the Jesuits have again had premises

since 1898, and they run a respected university, the "Pontificia

Facoltà Teologica dell'Italia Meridionale, San Luigi," located

on via Petrarca in the Posillipo section of the city (photo,

top).

Gestures, hand (2)

I

have a couple of young Neapolitan friends who are fans of American professional

sports, especially basketball and football. They enjoy NBA games on

TV and are fans of the local Naples pro basketball team. At the appropriate

time of the year, they turn out to practice with a local semi-pro Naples

football team sponsored by a local clothing store called "Original Marines".

That's the real name of the store, and that's the name the team have

emblazoned on their football jerseys when they play. It's strange to

see the bunch of them all decked out in football helmets, shoulder pads

and assorted body armor running around a field where people normally

play soccer. They endure a lot of good-natured ribbing from passers-by,

but it's all in fun. I

have a couple of young Neapolitan friends who are fans of American professional

sports, especially basketball and football. They enjoy NBA games on

TV and are fans of the local Naples pro basketball team. At the appropriate

time of the year, they turn out to practice with a local semi-pro Naples

football team sponsored by a local clothing store called "Original Marines".

That's the real name of the store, and that's the name the team have

emblazoned on their football jerseys when they play. It's strange to

see the bunch of them all decked out in football helmets, shoulder pads

and assorted body armor running around a field where people normally

play soccer. They endure a lot of good-natured ribbing from passers-by,

but it's all in fun.

One of

the things that most intrigues them about American sports is the way

US referees signal numbers with their fingers. I must say that it intrigues

me, as well. Times have changed. Number "one" (the raised index finger)

has stayed the same, but we used to make "two" with a simple "V" of

index and middle finger. I see referees now making "two" with the raised

index and little finger. In Naples and most anywhere in the Latin world,

that particular configuration of fingers is exclusively the sign of

the cuckold --the betrayed husband-- and the rudest hand gesture you

can make. It is enough to start fights --even, in certain circumstances,

fights to the death. It amuses my friends no end to see an American

referee giving 80,000 fans in the stadium—and who knows how many

more at home!—that sign from the middle of the field when it's

second down.

The number

3 is tricky. It was always hard, anyway. You had to use your thumb to

hold down the pinkie way over on the other side of your palm in order

for the three fingers in the middle to pop up. The new American “3”

is made by thumbing down the index finder and extending the middle,

ring, and little fingers. Some people find that an improvement, I know,

but these are the same people who have trouble with the Vulcan sign

for “Live Long and Prosper”. Four and five were, and remain,

easy.

Neapolitan

refs are torn between the two systems, I notice. They generally make

the sign for "one"—say, on first down—with the index finger,

although that number is usually signed elsewhere—maybe in a bar

to order one of anything—by a thumbs-up sign. "Two" is—again,

in a restaurant—a thumb and index finger, kind of like shooting

off an imaginary pistol toward the ceiling. Naples football refs are

unsure of this one and there is some talk of an ecumenical conference

to decide the issue; they use either the thumb/index finger version

or the "V" sign, but under no circumstances the new and improved cuckold

sign. "Three" in a restaurant and on the field is the extended thumb

and "V" sign—none of this prestidigitatious contortionism of having

to grapple with your own pinkie. Very few of my students at the university

of Naples can easily make either one of the American signs for 3 without

giggling as they struggle with it. Four and five are the same in both

Naples and the US: thumb down and all others up for "4" and everything

up for "5".

The only

trouble I ever had with "5" was in Greece, when I was made aware of

the fact that showing someone your outstretched palm in the manner we

would use to show "5" is the same as "giving the finger" to someone

in the US. I don't think they play American football in Greece.

Croce,

Benedetto (3), Filomarino (Palazzo)

Palazzo Filomarino della Rocca is most recently

well-known for having been the residence of the great Neapolitan historian

and philosopher, Benedetto Croce. The original structure was built

in the 1300s and was rebuilt and enlarged in the first decade of the

1500s. Subsequent modifications were added by the renowned architect

Ferdinando Sanfelice in the 1700s when the building passed into the

hands of Tommaso Filomarino della Rocca. He was responsible for the

addition of a fine library, as well, keeping with the intellectual

tradition of the premises, which had in the past hosted no less a philosopher

than Giovan Battista Vico. That tradition

still survives, as the building currently houses the Italian Institute

for Historical Studies founded by Croce. The building is on a long street

popularly known as "Spaccanapoli" (Naples-Splitter) in the historic

center of the city (see number 5 on the map of the historic center of Naples.). The section of

the street where the building stands is, today, named via Benedetto

Croce. Palazzo Filomarino della Rocca is most recently

well-known for having been the residence of the great Neapolitan historian

and philosopher, Benedetto Croce. The original structure was built

in the 1300s and was rebuilt and enlarged in the first decade of the

1500s. Subsequent modifications were added by the renowned architect

Ferdinando Sanfelice in the 1700s when the building passed into the

hands of Tommaso Filomarino della Rocca. He was responsible for the

addition of a fine library, as well, keeping with the intellectual

tradition of the premises, which had in the past hosted no less a philosopher

than Giovan Battista Vico. That tradition

still survives, as the building currently houses the Italian Institute

for Historical Studies founded by Croce. The building is on a long street

popularly known as "Spaccanapoli" (Naples-Splitter) in the historic

center of the city (see number 5 on the map of the historic center of Naples.). The section of

the street where the building stands is, today, named via Benedetto

Croce.

(Also see

here for a wartime episode in the life

of Croce.)

The

Imperial Port of Baia The

Imperial Port of Baia

Not

long ago, a piece of an oar was dredged up from the mud of Lake Lucrino,

the small body of water near Baia in the bay of Naples. Well, you

say, the Mediterranean is brimming with such bits of antiquity. What's

so special about this one? This one, it seems, was from a Roman ship,

a fighting vessel that was part of a fleet built nearby and that trained

here for its subsequent role in one of the most important naval engagements

in history. There are three such bodies of water in the area that

were crucial in Roman naval history and subsequently in the rise of

the Roman Empire: namely, Lake Lucrino, Lake Averno and the harbor

of Miseno.

Roman history

in the first century before Christ was marked by civil warand unrest.

The tumult came to a head with the assassination of Julius Caesar in

44 BC, an event that set the stage for the struggle to determine who

would rule Rome. That struggle was between Octavian, a great-nephew

of Julius Caesar, and Marc Antony. The latter was in league with Egypt

(and very in league with Cleopatra!), so the struggle could be said

to be between the forces of Rome and those of Egypt. The struggle was

decided in 31 BC at the Battle of Actium, a small dot on the Balkan

coast in northern Greece opposite the heel of the boot of Italy.

To fight

effectively at sea, the Romans had to change their traditional thinking.

For centuries, during the Punic Wars, the Macedonian Wars and endless

adventures against piracy in the Mediterranean, Rome had been content

not even to have her own real navy. Instead, she relied on using --renting--

small squadrons of vessels from her maritime allies, such as the Greek

city-states on the Italian mainland and on Sicily. It was a policy that

had worked but one that had more than once almost proved disastrous,

such as when Sextus attempted to cut off all supply routes in 40 BC,

almost succeeding in blockading Rome into submission.

Octavian,

thus, chose to build a fleet from scratch, and he chose his very able

deputy, Agrippa, to build and command it. Four-hundred ships were built

from the wooded areas near Naples and they trained on Lake Lucrino, a few miles north of Naples. (The lake

at the time of the Romans was much larger than the pond you see today.

The violent seismic activity in the 16th century that formed the hill

of Montenuovo right next to it also emptied most of the water.) Agrippa

joined Lake Lucrino to the adjacent Lake Averno and to the gulf of Cuma

by canals in order to form a single large naval base, portus Iulius.

(A chariot tunnel from Averno to Cuma was built at the same time and

has partially survived the ravages of time.)

The Roman

vessels were somewhat smaller than those of Marc Antony. The

Roman fleet that trained at Lucrino and Averno was made up of small,

fast triremes (sailing ships with three banks of oarsmen) as well as

"fives" and "sevens" (here, the number refers to the number of rowers

on each oar). The Romans specialized in speeding into close quarters

and boarding by grapnel to let their superb infantry swarm onto enemy

vessels. Antony's fleet, on the other hand, was the last great one in

history built along lines pioneered by the Greeks. Some of the ships

were monsters, virtual sea-going cities with boarding towers, artillery

and large infantry forces on board. They were propelled through the

water by sail and as many as ten rowers on a single oar.

The two

fleets, each of 400-500 vessels, met off of Actium. The Roman fleet

had been in battle a few years earlier. Marc Antony's fleet was green.

The battle, itself, was somewhat of an anticlimax. The Romans succeeded

in bottling up the Egyptians along the coast and picking them off little

by little until Queen Cleopatra decided to make a run for it. She got

away --and her fleet commander and lover, Marc Antony, sailed right

after her, deserting his men and ships! The disheartened Egyptian fleet

surrendered to the forces of Octavian, effectively ending the dispute

about who was going to rule Rome. Antony and Cleopatra did the Liebestod

thing, Octavian changed his name to Caesar Augustus, and all was right

with the world.

The third

important small body of water in the area (after Lucrino and Averno)

was Miseno, the natural harbor sheltered

by Cape Miseno near Cuma. Misenum actually referred to the pair of harbors

behind the cape: inner and outer, to the west and east, respectively.

They had been used for centuries by the Greek city-state of Cuma just

beyond the gulf. Caesar Augustus formed his first imperial fleet shortly

after the Battle of Actium. He had two main bases built in Italy: one

at Ravenna at the mouth of the Po river, and the other at Miseno. To

make Misenum suitable for its new role as an Imperial home port, the

Romans built new breakwaters and a freshwater reservoir of unparalleled

size. The outer harbor served the active vessels of the Roman navy and

provided room for training exercises, while its inner counterpart (to

which it was connected by a canal crossed by a wooden bridge) was designed

for the reserve fleet and for repairs, and as a refuge from storms.

The complex remained connected by canal and tunnel with Averno and Lucrino.

Because

of its location, Misenum controlled the entire Italian west coast, the

islands and the Straits of Messina. The Misenum fleet had a number of

secondary ports along the Tyrrhenian coast, probably at Ostia, Centumcellai

(modern Civitavecchia) and Calaris (Cagliari) in Sardinia. Eventually,

the Roman Empire would extend its Imperial fleets, with 'home ports'

at Alexandria, in Syria and Britain, as well as a river fleet in Germany.

The Misenum fleet, however, being one of the two Imperial fleets of

the Italian homeland, is referred to—as is the Ravenna

fleet—in Roman records as classes praetoriae, a

prestigious term, indeed, putting them on a par with the Imperial Guard,

the Praetorians. The importance of the Misenum fleet waned with the

integrity of the Roman Empire, itself. The fleet survived the periods

of unrest in the third century and was reorganized, but later proved

ineffective in keeping Constantine's ships from seizing Italian ports

in the struggles that led to the ultimate division of the Roman Empire

into two parts, east and west.

Gerolamini

Directly across from the Cathedral of Naples on via

Duomo is the large complex of the church and monastery of the Girolamini.

It is on the site of an earlier building, Palazzo Seripando,

which was donated to the disciples of San Filippo Neri in 1586. The

original building was demolished and construction started on the new

complex in 1592 on plans by the architect Giovanni Antonio Dosio. The

church is in the style of the Florentine Renaissance: a Latin cross

with three naves and lateral chapels. The entrance is on Piazzetta

Gerolamini around the corner on via dei Tribunali. Directly across from the Cathedral of Naples on via

Duomo is the large complex of the church and monastery of the Girolamini.

It is on the site of an earlier building, Palazzo Seripando,

which was donated to the disciples of San Filippo Neri in 1586. The

original building was demolished and construction started on the new

complex in 1592 on plans by the architect Giovanni Antonio Dosio. The

church is in the style of the Florentine Renaissance: a Latin cross

with three naves and lateral chapels. The entrance is on Piazzetta

Gerolamini around the corner on via dei Tribunali.

Members

of the order were called Girolamini because the premises were

the first site of the church of San Girolamo della Carità.

Much of the premises, including the impressive library and archives,

has been recently restored. Like many buildings from the period of the

Spanish viceroyship (1500-1700), this one, too, was “touched up”

by the great architects of the later Bourbon

period. In this case it was Ferdinando Fuga who redid the façade

in 1780.

Near the

entrance is the building where the philosopher Giambattista Vico lived for 20 years and that until

the middle of the 1700s, housed the Conservatory of the Poor of Jesus

Christ, an orphanage that trained children to be church musicians. It

is in Naples that this use of ‘Conservatory’ (a place where children

were ‘conserved’— hence, an orphanage) was, thus,

extended to mean a music school. The renovated premises house an impressive

art gallery and are the site of a number of exhibits throughout the

year.

Acton—

If

you read a little about Naples—or just walk around it a bit—sooner

or later you come across the name "Acton". Indeed, it is difficult to

keep your Actons straight. This, then, may help. If

you read a little about Naples—or just walk around it a bit—sooner

or later you come across the name "Acton". Indeed, it is difficult to

keep your Actons straight. This, then, may help.

The most

recent Acton relevant to Naples is Sir Harold Mario Mitchell Acton (1904-1994),

author of an authoritative 2-volume history of the kingdom of Naples

under the Bourbons, The Bourbons of Naples (1957) and The

Last Bourbons of Naples (1961). Harold Acton was one of the bright,

young intellectual lights of British university life of the 1920s and

such a supporter of new poetry that he once read Eliot's The Wasteland

through a megaphone at a garden party at Oxford. Acton was apparently

the inspiration behind Evelyn Waugh's fictional character, Anthony

Blanche, in Brideshead Revisited, who pulled the same stunt in

the novel.

Harold

Acton was born at Villa la Pietra, his family's estate near Florence.

He passed away there, as well, bequeathing his $500,000,000 estate,

including his Italian Renaissance villa and art collections to New York

University. A bizarre episode connected with the bequeathal is that

it was contested by five Italians who claim they are entitled to the

estate because their mother was the illegitimate daughter of Acton's

father, Arthur Mario Acton, making her Harold Acton's half-sister, whose

children would be entitled to the estate since Harold died without heirs.

The bizarre part is that earlier this year, an Italian court gave permission

to exhume Harold's earthly remains for DNA testing: I don't know if

that has been done.

The Acton

name in Naples goes back to Sir John Francis Edward Acton (1736-1811)

(anonymous portrait, above), an Englishman who served with such valor

in the service of the joint Spanish and Tuscan naval expedition against

Algiers in 1775 that he came to the attention of Queen Caroline of Naples

who acquired his services to reorganize the Neapolitan navy. He became

the commander of the navy, then the minister of finance, and then the

prime minister. He was also—according to most sources—the

Queen's lover. On the occasions of both flights of the royal family

to Sicily, first to escape the Neapolitan Republicans in 1799 and then the French

invasion of 1806, Acton accompanied them and returned with them.

Most notably, John Acton was responsible for the construction of the

new Royal Naval Shipyards at Castellammare di Stabia.

Vincenzo Cuoco, in his Saggio Storico sulla Rivoluzione

di Napoli, remarks that Acton was an astute judge of character and

the first one on the scene to really understand something that later

became evident to all—in Naples, the king, Ferdinand, was an absolute

dud; Queen Caroline ran the show. As an ally of the English and avowed

enemy of the new French Republic, he is seen as at least partially responsible

for provoking the French invasion of southern Italy that helped establish

the Neapolitan—or Parthenopean—Republic in 1799.

John Acton's

brother was General Joseph Edward Acton, who was also in the service

of the kingdom of Naples. Presumably, Joseph had children. I know nothing

about them, except that they will confuse any attempt at genealogical

straight-thinking on my part. Anyway, John got a papal dispensation

to marry his brother's 13-year-old (!) daughter. They had two children,

one of whom was Charles Januarius Edward (1803-1847), who eventually

became a cardinal in the Roman Catholic church and protector of the

English College at Rome. John's other son was Richard Acton, whose only

son was John Emerich Edward Dalberg Acton (1834-1902), the historian

and one of the great intellects of Victorian England. He is remembered

for writing The History of Freedom in Antiquity and The History

of Freedom in Christianity and for being the prime mover behind

the great Cambridge Modern History.

So, you

say (if you are still awake), all this is how the street, via Acton—the

road along the main port of Naples in front of the Maschio Angioino;got its name, right? No, that street

is named for another Acton—Ferdinand. Oh, there are two of them.

The first is Sir Ferdinando Acton (1801-1837), the gentleman who, in

1826, acquired the property for—and had built on that property—the

magnificent Villa Pignatelli, a building that still graces

the Riviera di Chiaia. I am not sure where Ferdinand came from—presumably

from another Acton, possibly John's brother, Charles (above).

Via

Acton, however, is named for the other Ferdinand Acton (1832-1891),

an officer in the Neapolitan navy and then, following the unification

of Italy, an admiral in the Italian navy and then Minister of the Navy.

Sources tell me that his father's name was Charles, so that might make

him the grandson or great-grandson of Charles, John's brother.

Or maybe

not.

Pozzuoli

The

Rione Terra, the old part of Pozzuoli

If

you are a city aiming at immortality, you could do worse than preserve

yourself in volcanic ash. That is, after all, what gave Pompeii and

Herculaneum their eerie foreverness— and gives us the pleasure

of being able to stroll their ancient streets, peeping into living rooms. If

you are a city aiming at immortality, you could do worse than preserve

yourself in volcanic ash. That is, after all, what gave Pompeii and

Herculaneum their eerie foreverness— and gives us the pleasure

of being able to stroll their ancient streets, peeping into living rooms.

Quite another

case is nearby Pozzuoli, just north of Naples. It is so worn down by

2,500 years, so overlaid with bits and pieces of successive civilizations,

that it is virtually impossible for the casual observer to recognize

it as the important city of the ancient world that it was. Excavations

are now going on and, ultimately, plans call for a museum, guided tours,

and the wherewithal to help you appreciate ancient Pozzuoli, just as

you do its Vesuvian cousins to the south. The project entails excavating

and restoring a 200 x 240 meter area of the Rione Terra, the

old city. Indeed an ambitious project.

The city

was founded in the middle of the sixth century b.c. by settlers from

Greece. Like those who founded nearby Cuma and

Parthenope (Naples) in those days along the same coast, these settlers

also chose a strategic promontory for their city. They named their new

home Dicaearchia ("Just Government"), a poetic name, presumably

making a point about the place they had fled, the island of Samos, ruled

by the tyrant Polycrates. As yet, archaeology has uncovered only the

most fragmentary physical evidence of this ancient Greek city. Dicaearchia

probably went into decline as its powerful neighbour, Cuma, became more

and more powerful. This idea is supported by the Greek historian Strabo,

who, in the first century before Christ, referred to the city (renamed

Putèoli by the Romans) as a "fortress raised on a cliff"

and as a "port of Cuma".

Around

the year 300 b.c. much of the Campania area, including Pozzuoli, came

under the domination of the Samnites,

the mortal enemies of the Romans, who ruled south-central Italy. The

Romans prevailed against Samnium and later against the Carthaginian,

Hannibal, who lay siege to Pozzuoli in 215. Putèoli became a

Roman colony in 194 b.c.

It is under

the Romans that Putèoli comes into its own. (Putèoli

was Latin for "little wells," referring to the many sulfur fumaroles

in the area. It has given modern Italian the term pozzilli, the

diminutive of "wells" and the name Pozzuoli for the city. The

popular idea that the name of the city comes from a similar Latin word,

puteo, meaning "smell," is cute, but wrong.) Cicero calls Putèoli

"little Rome", and Seneca tells us that it was a world port, receiving

fleets from around the Mediterranean, and, in turn, acting as a channel

for Campanian exports such as wrought iron, marble, mosaics and blown

glass. On his way to Rome, the Apostle Paul, himself, landed at Putèoli,

where he was welcomed by the Jewish community.

Adjacent, as it was,

to the mighty port for the Western imperial fleet at Miseno, built

by Caesar Augustus, Putèoli was a leading commercial center

and cosmopolitan city of the Roman world. Even before recent excavations

within the Rione Terra, Putèoli's importance was evident from

the ruins of the third largest amphitheater in Italy (photo, left).

It was begun under Nero and finished by Vepasian (69-79 a.d.). The

main and transverse axes measure 149 and 116 meters, respectively.

The structure could accomodate 20,000 spectators. The spaces beneath

the floor of the arena are still well-preserved and here it is possible

to see what complicated mechanisms were required to put on Roman spectacles

of the period, including the means to hoist wild beasts up to be released

into the open arena. Adjacent, as it was,

to the mighty port for the Western imperial fleet at Miseno, built

by Caesar Augustus, Putèoli was a leading commercial center

and cosmopolitan city of the Roman world. Even before recent excavations

within the Rione Terra, Putèoli's importance was evident from

the ruins of the third largest amphitheater in Italy (photo, left).

It was begun under Nero and finished by Vepasian (69-79 a.d.). The

main and transverse axes measure 149 and 116 meters, respectively.

The structure could accomodate 20,000 spectators. The spaces beneath

the floor of the arena are still well-preserved and here it is possible

to see what complicated mechanisms were required to put on Roman spectacles

of the period, including the means to hoist wild beasts up to be released

into the open arena.

There are also remnants of baths, a vast necropolis,

and columns from the ancient Temple of Augustus (originally a temple

for the worship of Jupiter and later incorporated into the Cathedral

of San Procolo). Near the harbor, also, there stands what is still erroneously

called the "Temple of Serapis," photo, left). Apparently, it was really

a market place. Now on dry land, the bases of the columns were underwater

until the 1980s, when significant seismic activity shifted the ground

level. (This is discussed in detail in a section of the entry on geology

that you may read by clicking here.) There are also remnants of baths, a vast necropolis,

and columns from the ancient Temple of Augustus (originally a temple

for the worship of Jupiter and later incorporated into the Cathedral

of San Procolo). Near the harbor, also, there stands what is still erroneously

called the "Temple of Serapis," photo, left). Apparently, it was really

a market place. Now on dry land, the bases of the columns were underwater

until the 1980s, when significant seismic activity shifted the ground

level. (This is discussed in detail in a section of the entry on geology

that you may read by clicking here.)

The fortunes

of Putèoli declined, of course, with those of the Roman Empire.

Before the arrival of the Normans at

the turn of the millennium and the subsequent foundation of the Kingdom

of Naples, Pozzuoli was part of the little known Duchy of Naples. Its

physical fortunes eroded further over the centuries: shifting

coastlines and constant earth tremors care nothing for the hard times

they may be preparing for future archaeologists. Severe seismic activity

had so weakened the ancient buildings of the Rione Terra that

the area was almost entirely evacuated in 1970.

The goal of present excavations (photo,

right) is to unearth the Roman city of Putèoli, including, of

course, the main street, the decumanus maximus, and the area

around the remnant columns of the Temple of Augustus. The digs are snaking

their way back from the entrance of the exhibit through a honeycomb

of Roman ruins, only a small portion of which are, as yet, part of the

display. Although no new physical bits of Decaearchia have been found,

plenty of Putèoli has. Fragments, for example, in a totally burned-out

section near ground level have been dated to the first century a.d.;

archaeologists speculate that a disastrous fire may have been caused

by the very seismic upheaval that presaged the eruption of Vesuvius

that buried Pompeii. The goal of present excavations (photo,

right) is to unearth the Roman city of Putèoli, including, of

course, the main street, the decumanus maximus, and the area

around the remnant columns of the Temple of Augustus. The digs are snaking

their way back from the entrance of the exhibit through a honeycomb

of Roman ruins, only a small portion of which are, as yet, part of the

display. Although no new physical bits of Decaearchia have been found,

plenty of Putèoli has. Fragments, for example, in a totally burned-out

section near ground level have been dated to the first century a.d.;

archaeologists speculate that a disastrous fire may have been caused

by the very seismic upheaval that presaged the eruption of Vesuvius

that buried Pompeii.

Recent

exhibits have been in the Palazzo di Fraja, in a section of the

building that once actually incorporated a Roman taberna, a shop,

into its own structure, thus hiding it for centuries. It has been partially

cleared and restored and is one of two such tabernae uncovered

since the present excavations began. The taberna is situated

near what is now believed to be the intersection of the main cross-roads

of the old center of Roman Putèoli. The exhibit displays approximately

200 items, ranging from ceramic items to statuary.

The Rione

Terra of Pozzuoli looks somewhat like a ghost town these days, due

to the evacuation and, now, the burrowing and scraping away going on.

Yet, this inconvenience to modern residents is a blessing for archaeologists,

since they are now free to probe in and under Strabo's "fortress raised

on a cliff" in their attempts to peel away the centuries.

Pergolesi,

Giovanni Battista (1710-36)

I

have it on good authority from an enthusiastic student at the Naples

Conservatory that the library in that institution is now totally

on-line, properly catalogued and up to date. It is no longer the case,

he assures me, "that there are shoe boxes in the basement with undiscovered

manuscripts of Pergolesi". I

have it on good authority from an enthusiastic student at the Naples

Conservatory that the library in that institution is now totally

on-line, properly catalogued and up to date. It is no longer the case,

he assures me, "that there are shoe boxes in the basement with undiscovered

manuscripts of Pergolesi". "Not that

there ever were," he adds.

I certainly

hope not. Pergolesi is in the forefront of important European musicians

of the early 1700s, and his influence on the development of subsequent

musical form in that century is far beyond what one might have expected

from a scant 26 years of life. He was born in Jesi, a small town not

far from Ancona in central Italy. He received early musical training

at home and then was sent to the Conservatorio dei Poveri di Gesù

Cristo in Naples, one of the four such institutions in the city

before they were consolidated into a single conservatory early in the

19th century. His teachers at the conservatory wrote of his great skill,

particularly as a violinist.

History

remembers Pergolesi largely for his contribution to what would become

the most popular form of entertainment in 18th century Europe, the opera

buffa -- the comic opera. His first

effort was Lo frate ’nnamorato (“The Enamoured

Monk”), performed at the Teatro dei Fiorentini in Naples on September

27, 1732. It was successful and is one of the few such works from

that period still performed. It was not, however, the one that "started

the ball rolling," so to speak. That honor goes to La serva padrona

(“The Maid Mistress”), composed as an intermezzo

within a larger work of his, Il prigioniero superbo (“The—[here,

superbo means “haughty,” “arrogant”]—Prisioner”),

performed for the first time in September 1733. La serva padrona

was quickly picked up in the repertoire of touring companies, and it

was one such performance in 1752 in Paris that drew the praise of Rousseau

and set off the so-called "War of the Buffoons," pitting the supporters

of traditional French opera against those of the newer opera buffa.

By general consensus, the opera buffa came out on top and defined "musical

comedy" as a discipline worthy of serious musical consideration—as

Mozart and Rossini would later confirm.

Pergolesi

wrote sacred music extensively; his Stabat Mater is still

performed, and, indeed, even crops up unexpectedly as background music

in film scores (In 2001, Space Odyssey, the large space ship

creeps slowly towards Jupiter accompanied by the delicate opening three-voice

soprano pyramid of the Stabat Mater.) Pergolesi was in Naples

when the Bourbon prince, Charles III,

moved in to reestablish the Kingdom of Naples as an independent state

after a few decades as an Austrian vice-realm, and Pergolesi's music

was among that chosen to celebrate the event at various masses held

throughout the city. He spent the last few months of his life in a Franciscan

monastery in Pozzuoli and died there of tuberculosis in 1736. Today,

a plaque on the church commemorates him.

Young,

Lamont (1); urbanology (6)

Lamont

Young and Utopian Naples

An

interesting tribute to the visionary, Lamont Young: a mural of his

1883 plan for an urban rail line for Naples adorns the walls of

a modern metro station.

|

Imagine

yourself in a gondola, gliding along a delicate waterway, now and again

passing beneath a quaint wooden bridge. Trees line and shade the footpaths

on either side of the canal, and gentlemen and gentleladies are out

strolling along the banks. Gracious villas are set back from the water's

edge, and the faint melodies of late summer are in the air. Your spirit

quickens a bit as the narrow waterway makes a final gentle bend and

opens onto the majestic Grand Canal, lined by stately façades

and crossed by picturesque bridges as it carries pleasure craft out—to

the Bay of Naples! Imagine

yourself in a gondola, gliding along a delicate waterway, now and again

passing beneath a quaint wooden bridge. Trees line and shade the footpaths

on either side of the canal, and gentlemen and gentleladies are out

strolling along the banks. Gracious villas are set back from the water's

edge, and the faint melodies of late summer are in the air. Your spirit

quickens a bit as the narrow waterway makes a final gentle bend and

opens onto the majestic Grand Canal, lined by stately façades

and crossed by picturesque bridges as it carries pleasure craft out—to

the Bay of Naples!

Grand Canal?

Bay of Naples? But, surely, we are in Venice. Not exactly. We're in

the Venice Quarter of Naples, part of an unfulfilled utopian scheme

to change the city in the years before the turn of the century.

Change