©

2004 Jeff Matthews & napoli.com

Municipio,

Piazza

The importance in Naples of Piazza Municipio—City

Hall Square—goes back to the days of the Angevins, when the Maschio

Angioino, the New Castle, was built. The castle and area around it

thus became the symbol of authority. Besides the castle, a new Angevin

harbor was built on the sea directly in front of the castle. Later, the

Aragonese and then the Spanish expanded the fortifications, such that

at its height, the castle housed the royal armory, foundry and the corps

of the Royal Guards, essentially taking up most of the space of the present-day

square. In the late 1800s, the urban renewal

of Naples started to give shape to the area around the castle and

began to transform it into the Piazza Municipio we see today. (This

photo looks down on Piazza Municipio from the Maschio Angioino. The center

of the square is cluttered with construction equipment for the new subway

station.) The importance in Naples of Piazza Municipio—City

Hall Square—goes back to the days of the Angevins, when the Maschio

Angioino, the New Castle, was built. The castle and area around it

thus became the symbol of authority. Besides the castle, a new Angevin

harbor was built on the sea directly in front of the castle. Later, the

Aragonese and then the Spanish expanded the fortifications, such that

at its height, the castle housed the royal armory, foundry and the corps

of the Royal Guards, essentially taking up most of the space of the present-day

square. In the late 1800s, the urban renewal

of Naples started to give shape to the area around the castle and

began to transform it into the Piazza Municipio we see today. (This

photo looks down on Piazza Municipio from the Maschio Angioino. The center

of the square is cluttered with construction equipment for the new subway

station.)

Much

of the transformation had to do with enlarging the port area and building

new facilities for shipping. The final touch in that transformation

didn’t come until the construction of the new Maritime Passenger

Terminal (photo, right) in 1939. It is of the same monolithic architecture

as the main Post Office, also a product of architecture under Fascism.

Large and imposing, they represent the last great building splurge in

Naples until the very recent investment in skyscraper technology in

the new Civic Center at the extreme east end of town.

The clearing of the area around the port during the 1890s affected Piazza

Municipio and the entire east-west axis along the old port, doing away

with many of the buildings from the 1700s and leaving intact only a

few bits and pieces of the old city wall for reasons of historical interest

(one of which is the nearby Church of the

Incoronata on via Medina). The present day Municipio (City

Hall) (seen, partially hidden, in the center of the top photo) at the

north end of the square is called Palazzo

San Giacomo because it incorporates an ex-monastery

of that name built by the Spanish in the 1500s. (The adjacent church

of the same name still functions as a church.) The Municipio, itself,

dates back only to the early 19th century. It was an example of advanced

architectural technology at the time, utilizing glass for an internal

passageway that connected the square in front with the main street,

via Toledo in the rear. That advantage was undone by the recent construction

of the Bank of Napoli on via Toledo, effectively closing the passage.

Thus, the entire square, from the port to the Municipio is spacious

and grand, and it was from here that the urban renewal of Naples in

the late 1800s started.

Virtually

all of the buildings, including the nearby Galleria Umberto represent the new idea at the turn-of-the-century

of building shop and office space for the middle-class. From Piazza

Municipio, then, the clearing continued to the east down to Piazza

Bovio where the beginning of a new broad avenue, Corso

Umberto, would be built.

The current

(2003) excavation and contruction in the middle of the square is for

the "Municipio" stop of the new underground Metropolitana train line.

It will connect to stops further east at Piazza della Borsa,

then via Duomo, and, finally, the central train station at Piazza

Garibaldi, essentially running parallel to and over the walls of

the ancient Greco-Roman city of Neapolis. What is now Piazza Municipio

was well outside those walls, but, nevertheless, the digging has uncovered

some interesting archaeological finds, including the outer fortifications

of the fortress, erected by the Spaniards in the 1500s.

Evil

eye, luck (good & bad) (3), malocchio

I

came across this interesting item in the on-line version of the 1911

Encyclopaedia Britannica. In the section on Naples, there is

a paragraph about folk-lore and, specifically, how Neapolitans ward

of the "evil eye": I

came across this interesting item in the on-line version of the 1911

Encyclopaedia Britannica. In the section on Naples, there is

a paragraph about folk-lore and, specifically, how Neapolitans ward

of the "evil eye":

| ...charms

against the Evil Eye...were all derived from the survival of ancient

classical legends... These may be divided into three classes:

first, the sprig of rue in silver, with sundry emblems attached

to it, all of which refer to the worship of Diana, whose shrine

at Capua was of considerable importance; secondly, the serpent

charms, which formed part of the worship of Aesculapius, and were

no doubt derived largely from the ancient eastern ophiolatry;

and lastly charms derived from the legends of the Sirens...The

sea-horse and the Siren alone are commonly found as charms... |

I had never

heard any of that. There are a few terms used for "evil eye," "bad luck,"

etc. in Italian, in general, and in southern Italy, in particular. Simple

"bad luck" is sfortuna, which is about the same as "misfortune"

in English; there is no implication of it having been caused. The "evil

eye," however—malocchio, in Italian—is much different.

That is misfortune "cast" on you by a malevolent person with that particular

ability. Indeed, one of the common Neapolitan terms for that kind of

bad luck is jettatura, which comes from the Italian verb "gettare,"

meaning "throw" or "cast". Another common word in both Italian and Neapolitan

for "witchcraft" is fattura, from the root "make," or "do". (Fattura,

fittingly, is also the name for the receipted invoice you have to give

someone if you sell them something, so you can't get out of paying a

tax on your profit. Witchcraft, bad luck, taxes. I rest my case.)

In any

event, the most common way to ward off the Evil Eye, or bad luck caused

by a spell, is by making the "sign of the horns"—le corna—(see here), that is, extending the index and little

fingers of the hand and waggling your hand towards the ground. You can

also buy a lucky charm in the shape of a single curved horn. There are

two explanations for the use of the horns as a good luck charm: one

says that it comes from the defensive posture of animals: head lowered,

horns ready to use; the other—more likely—is that it has

to do with the sexual vigor implied in the symbol of the male animal.

Phallic symbols are also commonly seen throughout the Greek and Roman

world as good luck charms. That explanation seems more likely to me,

since another common way for men in Naples to ward off bad luck is to

touch their genitals. (Touching someone else's genitals, on the other

hand, generally causes more bad luck.) Depending on the threshold of

superstition on a given day in Naples, then, you can get some interesting

body language going on in public and broad daylight on any street in

the city.

I was not

familiar with rue—or any other plant—as a charm against

the Evil Eye. I asked a friend about this and she immediately cited

a verse to me:

"Aglio,

fravaglie, fatture ca nun quaglie...," a dialect verse meaning

"Garlic and animal innards keep away bad luck." Then, all the vampire

books and movies with which I afflicted my childhood came back to me

and I remembered about garlic. There is a whole class of plants that

are used medicinally and—in folklore—to cast spells and

ward them off. Rue (ruta graveolens) is one of them. In some

sources, it is the famous "moly plant" used by Ulysses in The Odyssey

(book 10, lines 304-6) to protect himself and his men from the spell

of the Circe. Yet, I have not seen sprigs of rue for sale on the streets

of Naples in the way that you find little horn amulets.

Serpent

charms and ophiolatry (serpent worship) are equally hard to find in

Naples. It occurs to me that some of the amulets I see in street stalls—charms

that I have always taken to be single horns—are, in fact, curved

and, if not coiled, at least "wiggly". Maybe it was originally meant

to be a snake. The only Naples myth I know about snakes has to do with

how Virgil is said to have used his magical powers to drive away a great

serpent that lived beneath the hill of the city. (See here for a relevant entry.) I am also aware

of the split in our mythology between the benevolent and malevolent

attributes of snakes. Contrasting the evil seducer/serpent in the book

of Genesis, we have in other contexts the benevolent presence of twin

serpents on the caduceus, the symbol of the medical profession, and,

further to the east, in Indian mythology, the cobra that protects Buddha

by spreading its hood over him.

I have

seen the sea-horse and siren symbols a lot in Naples, but I didn't know

that they were good luck charms—nor did any of the people I spoke

to. As they say in the ivory towers of academe: more research is needed.

Gesù

Nuovo, church & square; Santa

Chiara, church (1)

Piazza

del Gesù Nuovo may be considered the bridge between the ancient

Greco-Roman city of Neapolis and the city of the Spanish vicerealm that

was to expand to the west in the 1500s under the direction of the Viceroy

Don Pedro di Toledo. Under the earlier Angevin rule, there had been

a western gate to the city at Piazza del Gesù that the

Spanish simply moved over to Largo Mercatello (modern-day Piazza

Dante), when they built the grand avenue now known as via Toledo

(or via Roma).

The square,

Piazza del Gesù Nuovo, contains some remarkable structures.

First, there is the thirteenth-century Gothic church/convent of

Santa Chiara, marked most obviously by the belfry (photo, left) that

stands within the grounds at the end of the square. The convent was

built between 1310 and 1328 at the behest of the wife of King

Robert of Anjou. It still retains the citadel-like walls setting it

apart from the outside world, walls that contained a vast religious

community—and today contain a more modest one—made up of

the Convent of the Poor Clares and, beside it, a monastery of Grey Friars,

both dominated by the stark architecture of the church itself. The complex

was expanded along Baroque lines in the 1700s. It was almost entirely

destroyed by bombing in WW II and was restored to its original Gothic

form, retaining only a few reminders of the Baroque. King’s Robert’s

tomb is within the church, and bears the epitaph by Petrarch: Cernite

Robertum regem virtute refertum, reminding the people to “consider

Robert a King rich in virtue”.

The

lovely monastic courtyard in the rear of the church is the result of

a renovation done by D.A. Vaccaro in the 1730s, apparently at the request

of Maria Amalia di Sassonia, wife of Charles III of Bourbon, King of Naples. The colorful

and delicate majolica tilework is characteristic of the school of Neapolitan

ceramic from that period and was crafted by Donato Massa and his son,

Giuseppe.

The most striking building in the square—other

than the church of Santa Chiara—is the fifteenth century residence

built for Robert Sanseverino, Prince of Salerno. It is now the Church

of Gesù Nuovo (photo, left) and has given its name to the entire

square. (It is one of those churches in Naples that started out as something

else. The word "new" in the name of the church is to distinguish it

from the church of Gesù Vecchio (old) about a half-mile away.)

The unusual façade is called "ashlar" in architectural terminology

and is one of the few examples of this characteristic 15th-century façade

in Naples.The building was finished in 1470 and was somewhat of

a symbol of the baron's increasing power and favor within the court

of Ferrante of Aragon, ruler of the Kingdom of Naples at the time. The

baron died shortly thereafter and the building passed to his son, Antonello. The most striking building in the square—other

than the church of Santa Chiara—is the fifteenth century residence

built for Robert Sanseverino, Prince of Salerno. It is now the Church

of Gesù Nuovo (photo, left) and has given its name to the entire

square. (It is one of those churches in Naples that started out as something

else. The word "new" in the name of the church is to distinguish it

from the church of Gesù Vecchio (old) about a half-mile away.)

The unusual façade is called "ashlar" in architectural terminology

and is one of the few examples of this characteristic 15th-century façade

in Naples.The building was finished in 1470 and was somewhat of

a symbol of the baron's increasing power and favor within the court

of Ferrante of Aragon, ruler of the Kingdom of Naples at the time. The

baron died shortly thereafter and the building passed to his son, Antonello.

Young Tony,

however, quickly became enmeshed in conspiracy against the throne and

was forced to flee the city of Naples and hole up in a fortress near

Salerno. He was captured and exiled to Senigallia (no, not Senegal—it's

a town on the Adriatic). His property was confiscated. He eventually

got the property back from the Spanish throne when they took over the

kingdom. The large residence then passed to his son, Ferrante. In 1547,

Ferrante incurred the wrath of the Spanish viceroy, Don Pedro Alvarez

de Toledo, and fled the kingdom, dying in Avignon, France, in 1568.

His property was put up for sale and the residence was bought by Nicolò

Grimaldi in 1584 who, in turn, sold it to the Jesuit order. It was transformed

into a church, leaving the original façade intact, and was consecrated

in 1601. The church passed to a Fransiscan order when the Jesuits were

expelled from Naples in 1767. The Jesuits got the church back in 1821.

The highly

ornamental interior of the church belies its solemn exterior. The spectacular

frescos on the ceiling of the central nave are by Belisario Corenzio

and Paolo de Matteis. Also, the church has on display The Expulsion

of Heliodorus from the Temple (1725) one of the most noteworthy

works by Francesco Solimena, the great painter of the Neapolitan Baroque.

The building,

because of its checkered history, first as a residence, then as a church—what

with people getting exiled, dying, etc. etc.—used to have somewhat

the reputation of being under an evil spell. Some students of the supernatural

have enjoyed attributing this malevolent presence to the esoteric properties

of the stones in the unusual façade.

Literally "topping off’ the square is the Spire

of the Immaculate Virgin, erected in 1750 with funds collected through

public subscription sponsored by Jesuit Father Francesco Pepe. The spire

replaced an earlier equestrian statue erected in 1705 on the occasion

of a visit to Naples by Philip V of Spain. When the Spanish left the

city and were replaced by the Austrians, that statue was destroyed by

the populace. Literally "topping off’ the square is the Spire

of the Immaculate Virgin, erected in 1750 with funds collected through

public subscription sponsored by Jesuit Father Francesco Pepe. The spire

replaced an earlier equestrian statue erected in 1705 on the occasion

of a visit to Naples by Philip V of Spain. When the Spanish left the

city and were replaced by the Austrians, that statue was destroyed by

the populace.

Some of

the finest sculptors of the 1700s worked on the spire ones sees today:

among others, Francesco Pagani and Matteo Bottiglieri. Depicted on the

spire, among other scenes, are the Presentation of Jesus at the Temple;

The Birth of the Virgin Mary; and The Annunciation. The spire, itself,

represents the presence of the Jesuit Order in the city. Its rich ornamentation

is considered the epitome of Neapolitan Baroque sculpture.

Amalfi (1)—

Amalfi. In 337 a.d., Roman patricians on their way to

Constantinople were shipwrecked along so stunningly beautiful a coast

that they understandably decided to stay marooned and let war and empire

pass them by. Centuries hence, the 19th century Italian writer, Renato

Fucini, would say: "When the inhabitants of Amalfi get to heaven on

Judgment Day, it will be just like any other day for them." Amalfi. In 337 a.d., Roman patricians on their way to

Constantinople were shipwrecked along so stunningly beautiful a coast

that they understandably decided to stay marooned and let war and empire

pass them by. Centuries hence, the 19th century Italian writer, Renato

Fucini, would say: "When the inhabitants of Amalfi get to heaven on

Judgment Day, it will be just like any other day for them."

For centuries

thereafter—in the turmoil following the dissolution of the Western

Roman Empire—Amalfi remained one of the small coastal enclaves

ruled nominally by the Byzantine Empire. Finally, in 839, Amalfi was

conquered by the Duchy of Benevento, itself a Longobard holdout against

Byzantium. Benevento was badly in need of a port, and though there is

little documentation of that period, the fact that Benevento bothered

to take Amalfi at all may mean that the place had already developed

into a port of some importance.

Upon the

death of the Duke, Amalfi freed itself from Benevento and went into

business for itself. In 957, the head of Amalfi took the title of Duke,

putting himself on an equal level with other rulers of the area. Little

by little, the Amalfi fleet expanded and spread throughout the Mediterranean.

Many places throughout the Mediterranean still have small churches to

Saint Andrew, patron saint of Amalfi—churches built by Amalfi

seafarers centuries ago. They established a strong presence in Antioch,

and especially Constantinople, where they were the single greatest group

of merchants in the commerce between East and West, taking an active

political and economic role in the life of the Byzantine Empire.

In Constantinople in the middle of the tenth century, there was an "Amalfi

Quarter," replete with schools and stores. And in Jerusalem the Amalfitans

founded the Order of the Knights, which later became the famous Order

of Malta.

The height of the Maritime Republic of Amalfi came at about the

turn of the millennium, when Amalfi was a great exporter of wood and

iron, and importer of spices, carpets, silk, and perfumes from the Orient,

goods that found a market in the Papal States to the north and all the

cities in the south of Italy. The cathedral of Amalfi (photo, left)

is from that period. It was built in 1066 and still has the portals

imported from Constantinople (also see here).

Like the other maritime republics, Amalfi even coined its own money,

the Tarì. Also, Amalfi was where the first Maritime Code,

the so-called tavole amalfitane, was formulated, a code that

regulated maritime trade in the Mediterranean from the 1000s to the

1500s and that served as a model for future maritime law. Here,

they say, too, is where Flavio Gioia invented the compass—or at

least improved upon the device borrowed from the Arabs. The height of the Maritime Republic of Amalfi came at about the

turn of the millennium, when Amalfi was a great exporter of wood and

iron, and importer of spices, carpets, silk, and perfumes from the Orient,

goods that found a market in the Papal States to the north and all the

cities in the south of Italy. The cathedral of Amalfi (photo, left)

is from that period. It was built in 1066 and still has the portals

imported from Constantinople (also see here).

Like the other maritime republics, Amalfi even coined its own money,

the Tarì. Also, Amalfi was where the first Maritime Code,

the so-called tavole amalfitane, was formulated, a code that

regulated maritime trade in the Mediterranean from the 1000s to the

1500s and that served as a model for future maritime law. Here,

they say, too, is where Flavio Gioia invented the compass—or at

least improved upon the device borrowed from the Arabs.

The fortune

of Amalfi changed dramatically for the worse in the 1100s. Three things

happened. First, the powerful Normans, who would eventually take over

all of southern Italy to found the Kingdom of Naples, took the city

in 1131. With that, Amalfitan independence ceased. Second, the town

was sacked by the maritime competition, Pisa, in 1135 and again

in 1137. Third, Amalfi failed to participate in the first Crusade, leading

further to its decline, and to the rise of competing maritime republics

in the north of Italy. Somewhat later, in 1343, a powerful earthquake

destroyed the port of Amalfi, administering a belated coup de grace

to the once proud maritime power.

If you

visit Amalfi today, you can still see the ruins of what was the largest

naval shipyard in medieval Europe. As well, you can visit a restored

and functioning paper mill, recalling the days when the Amalfitans took

the art of paper-making from the Arabs and made it their own, turning

out precious paper products for export throughout the Mediterranean.

The tradition of nostalgic paper-making continues to this day, and you

can buy characteristic replicas of historic Amalfi letter paper, cards,

maps, etc. Also, the area—like much of southern Italy—is

marked by the presence of Saracen towers,

built to guard against incursions by the Arabs and, later, the Turks.

Worthy of attention in Amalfi is the Civic Museum, which has the only

remaining copy of the Amalfi Maritime Code, mentioned above.

The current

accessibility of Amalfi by vehicular traffic is due to the road-building

enthusiasm of Ferdinand II of Bourbon,

King of Naples, in the mid-nineteenth century, who opened a road all

along the Sorrentine peninsula and over to the Amalfi coast. (Also see

here.)

Russo,

Vincenzo

It

is not widely known that there was an active Neapolitan offshoot of

the French Enlightenment just as dedicated as mid–18th–century

French intellectuals to discussions of the Rights of Man (and even the

Rights of Woman), the decadence of monarchies, and democracy and republicanism

as societal goals worth striving for—and even worth having a revolution

for. The French Revolution is amply documented. The Neapolitan Revolution

of 1799 is not well documented—at least in English—but there

is some material in these pages: It

is not widely known that there was an active Neapolitan offshoot of

the French Enlightenment just as dedicated as mid–18th–century

French intellectuals to discussions of the Rights of Man (and even the

Rights of Woman), the decadence of monarchies, and democracy and republicanism

as societal goals worth striving for—and even worth having a revolution

for. The French Revolution is amply documented. The Neapolitan Revolution

of 1799 is not well documented—at least in English—but there

is some material in these pages:

The

Bourbons, part 1

Eleonora

Fonseca Pimentel

Cardinal

Ruffo

Two

prominent figures connected with the Neapolitan Enlightenment are discussed

elsewhere on this website: Gaetano Filangieri

and Vincenzo Cuoco . Another such person

worth mentioning is Vincenzo Russo.

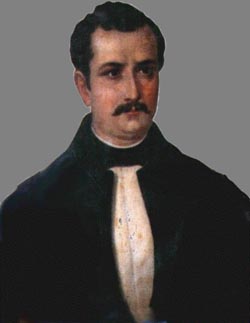

Russo

was born on June 16, 1770 in Palma Campania, a small town about halfway

between Naples and Avellino. His father, Nicola, was a lawyer. His mother

was Mariangela Visciano from San Paolo Belsito. At the age of

eight, he began attending the seminary in Nola, and at 13 he went to

Naples with his brother Joseph to start his studies of the law. There

he became a member of a Masonic lodge and was attracted to the new ideas

of reform and democracy, in particular the ideals that would drive the

French Revolution. He started to attend secret meetings of the "Republican

clubs," so-called in imitation of those in France. These societies in

Naples of that period typically immersed themselves in the works of

their fellow Neapolitans, Gaetano Filangieri

and Mario Pagano* [see note, below], as well as the writings of

the likes of Montesquieu, Rousseau, Voltaire, and Locke.

When

the French fleet came to Naples in 1792 to try to gain diplomatic recognition

from the Bourbons of the French Republic, Russo was one of those who

took part in meetings with admiral Latouche Treville. Yet, with the

Bourbon monarchy running scared before potential French revolutionary

contagion in Naples, Russo was one of a number of local "republicans"

accused of conspiracy against the monarchy in 1792. Some were

actually executed, but he was let off. Later, in 1797, under the similar

circumstances of what was apparently an active Jacobin conspiracy within

the kingdom, he was forced to flee the kingdom.

He

took refuge in Switzerland where he took up the study of medicine. He

moved to Milan and then Rome and was in that city when the Roman Republic

was declared in February of 1798. He wrote for the Monitore di Roma.

He took a radical and anticlerical line. When Ferdinand IV of Naples

decided to march north and liberate the Roman Republic, Russo enlisted

as a doctor in a company of Neapolitan exiles serving in the French

army. The Bourbon army was routed in the field and fled back to Naples,

pursued by the French, which episode eventually led to the flight of

the royal family to Sicily and the proclamation of the Neapolitan Republic

in January 1799. At that point, Russo became active in the government

of the Republic and was appointed elector for the Volturno region. On

Feb. 10, because of his exceptional skill as a speaker, he was put in

charge of the ministry of public instruction for the new republic, charged

with explaining the actions of the government to the average citizen

and with encouraging political discussion.

He

was put in charge of organizing resistance in Calabria to Ruffo's royalist Army of the Holy Faith that eventually

overthrew the Republic, and he was in the front line at the Republic's

"last stand", the battle of the Ponte della Maddalena, just outside

of Naples. The battle and the war went against the Republic, and Russo

was wounded and taken prisoner. He was put on trial with 1000 other

Republicans and charged with being a zealous member of the Republican

government (which he was) and with besmirching the name of his monarch

(certainly true). He was sentenced to death and was hanged on the November

19, 1799 in Piazza Mercato. His last words were: "I die free and for

the Republic."

During

Russo's exile in Switzerland, he had started to write Pensieri Politici

(Political Thoughts), the work for which he is remembered. It was eventually

published in 1798 and is an expression of Russo's egalitarian interpretation

of the values of the French Enlightenment. There are 45 short chapters,

each bearing succinct titles such as "Revolution," "The Law," "Religion,"

"Education,"—in short, Russo's view on how society should be constructed.

It is Rousseauvian in that he believed in an ideal and simple human

condition, free from the corruption of wealth and social class. The

ideal society would be egalitarian and populated by educated small farmers

all working for the common good. Private property would not exist and

money would eventually be unnecessary. He affirmed the necessity of

achieving such economic and social transformation through revolution,

revolution being an instrument of education as well as one of social

change.

He

was called a "Neapolitan Saint-Just" by some of his contemporary detractors—this

in reference to Antoine Louis Leon de Richebourg de Saint-Just (1767—1794),

the pitiless and tyrannical "angel of death" of the French Revolution

and friend of Robespierre, who apparently enjoyed sentencing people

to the guillotine. Such a comparison is not warranted in the case of

Vincenzo Russo. Neither he nor the Neapolitan Republic was bloodthirsty.

There were no loppings-off of royalist heads in the six or seven months

of life enjoyed by the Republic. Russo was, however, argumentative and

uncompromising in his dedication to revolutionary ideals such as doing

away with feudal land rights. He no doubt irritated a lot of people.

He was not a hypocrite, and often gave his salary back to the state,

encouraging others who could afford it to do the same. That probably

irritated some people, as well. As noted, he went to the battlefield

when it counted, and, with the likes of Eleonora

Fonseca Pimentel, he was one of the many bright lights of the Republic—collectively,

the flower of Neapolitan culture—executed for their efforts.

[*Mario

Pagano was some 20 years older than Russo and by the time of the French

Revolution already a noted jurist and legal scholar in Naples. He was

a supporter of the Neapolitan Republic in 1799 and was instrumental

in the drafting of the constitution. He had also been an active defender

of those accused of conspiracy against the monarchy in the early 1790s.

He, too, was executed when the Republic fell.]

Easter

Monday (Pasquetta)

| And,

behold, two of them went that same day to a village called Emmaus…and

they talked together of these things which had happened…[and]

Jesus himself drew near and went with them… (Luke 24:13-15) |

The

Monday after Easter is called "Monday of the Angel," in Italian, but,

more commonly, "Pasquetta"—a diminutive of "Pasqua"—Easter.

It commemorates the meeting (recounted in the Bible, above) of the risen

Christ with his disciples in Emmaus, a village near Jerusalem, on the

Monday after the Resurrection. To recall the disciples' walk from Jerusalem

out to the nearby village, it is still customary in many parts of Italy

for people—especially young people—to go on an outing. The

Monday after Easter is called "Monday of the Angel," in Italian, but,

more commonly, "Pasquetta"—a diminutive of "Pasqua"—Easter.

It commemorates the meeting (recounted in the Bible, above) of the risen

Christ with his disciples in Emmaus, a village near Jerusalem, on the

Monday after the Resurrection. To recall the disciples' walk from Jerusalem

out to the nearby village, it is still customary in many parts of Italy

for people—especially young people—to go on an outing.

This custom

easily makes Pasquetta the most hectic, bustling day of the year in

Naples. Last–minute Christmas shopping, Mardi Gras celebrations,

New Year's Eve, rowdy bands of football hooligans—all of that

is nothing compared to the Monday after Easter. Every single teenager

who is upright and breathing puts on a knapsack packed with food and

sets out to go somewhere—anywhere. But not alone. They travel

in packs, herds, swarms, or whatever the appropriate collective noun

is for a carefree mob out for a picnic in celebration of a religious

event they no longer remember anything about.

The

Biblical verses tell us that Emmaus was about "threescore furlongs"

from Jerusalem. If the translators of the King James Bible and I are

using the same single AA-cell-driven calculator, that rounds off to

about 7½ miles. It goes without saying that Neapolitan teenagers

of today are not about to walk 7½ miles to commemorate anything,

but they will take the train. The local narrow-gauge iron horse that

runs from Naples to Sorrento is called the Circumvesuviana. It makes

almost 30 stops on the way out; many of these stations are on the slopes

of Vesuvius in what is the most-densely populated area in Europe. All

of these kids populate densely onto that train on Pasquetta and go somewhere.

I have been on the train on Pasquetta and actually had kids come over

and sit on me! They will also take the boat. I have been on the ferry

to Capri on Pasquetta. We were packed to the gunwales with teenagers,

each of whom carried his or her own weight in obnoxious very loud portable

music toys—and I say that without even knowing where the gunwales

of a ship are located. The

Biblical verses tell us that Emmaus was about "threescore furlongs"

from Jerusalem. If the translators of the King James Bible and I are

using the same single AA-cell-driven calculator, that rounds off to

about 7½ miles. It goes without saying that Neapolitan teenagers

of today are not about to walk 7½ miles to commemorate anything,

but they will take the train. The local narrow-gauge iron horse that

runs from Naples to Sorrento is called the Circumvesuviana. It makes

almost 30 stops on the way out; many of these stations are on the slopes

of Vesuvius in what is the most-densely populated area in Europe. All

of these kids populate densely onto that train on Pasquetta and go somewhere.

I have been on the train on Pasquetta and actually had kids come over

and sit on me! They will also take the boat. I have been on the ferry

to Capri on Pasquetta. We were packed to the gunwales with teenagers,

each of whom carried his or her own weight in obnoxious very loud portable

music toys—and I say that without even knowing where the gunwales

of a ship are located.

All that

may be in keeping with something I've just read about Easter Monday—that

early Christians celebrated the days immediately following Easter by

telling jokes and playing pranks. I had never heard that before, and

I am not sure how much better off I am now that I know it. In any event,

the disciples did not enjoy such modern amenities as portable CD players

and cell-phones beeping in 20 different keys at the same times. One

wonders how they passed the time on their walk. The best thing to do

on Easter Monday in Naples is stay home.

San

Domenico Maggiore, Piazza

One of

the most interesting squares in the city of Naples is Piazza San

Domenico Maggiore. The square is on "Spaccanapoli" (named via

Benedetto Croce at this particular section of its considerable length)

the street that "splits" the historic center of Naples and that was

one of the three main east-west streets of the original Greek city of

Neapolis.

In the

center of the square is an obelisk topped by a statue of San Domenico

di Guzman, founder of the Dominican Order, erected after the plague

of 1656. The original designer of the spire was the great Neapolitan

architect, Cosimo Fanzago, among whose other works is the San Martino

monastery on the hill overlooking the city. Construction on the spire

was started immediately after the plague epidemic of 1656 but was suspended

in 1680 when the spire had reached about half the height one sees today.

It was finished in 1737 under Charles III, the first Bourbon monarch

of Naples.

The most prominent

building on the square is, of course, the Church of San Domenico Maggiore

(photo on left) . The church one sees today incorporates a smaller,

original church built on this site in the tenth century, San Michele

Arcangelo a Morfisa, a Byzantine church that housed the Basilian monastic

order. The original entrance is still visible to the left in the square

at the top of an outside stairway (seen in the next photo, below). After

the Schism between Rome and Constantinople, that church became a Benedictine

monastery in 1116 and then passed to the Dominican order in 1221. Charles

II of Anjou began the extensive rebuilding that produced the Church

of San Domenico Maggiore. The work was done between 1283 and 1324, but

the church has undergone extensive modifications over the centuries,

including one in 1670 that recast the structure in the style of the

Baroque. In the 19th century, however, the church was restored to its

original Gothic design. The most prominent

building on the square is, of course, the Church of San Domenico Maggiore

(photo on left) . The church one sees today incorporates a smaller,

original church built on this site in the tenth century, San Michele

Arcangelo a Morfisa, a Byzantine church that housed the Basilian monastic

order. The original entrance is still visible to the left in the square

at the top of an outside stairway (seen in the next photo, below). After

the Schism between Rome and Constantinople, that church became a Benedictine

monastery in 1116 and then passed to the Dominican order in 1221. Charles

II of Anjou began the extensive rebuilding that produced the Church

of San Domenico Maggiore. The work was done between 1283 and 1324, but

the church has undergone extensive modifications over the centuries,

including one in 1670 that recast the structure in the style of the

Baroque. In the 19th century, however, the church was restored to its

original Gothic design.

Among the

many artistic points of interest in the basilica is the frescoed ceiling

by Francesco Solimena (1707), one of the most prominent of Neapolitan

Baroque painters. The church also holds the tombs of a number of Aragonese

princes from the fifteenth century. Other prominent figures repose here,

as well: for example, Cardinal Fabrizio Ruffo,

head of the loyalist Army of the Santa Fede, which brought down the

Parthenopean Republic in 1799.

The monastery

annexed to the church has been the home of prominent names in the history

of religion and philosophy. It was the original seat of the University

of Naples, where Thomas Aquinas, a former monk at San Domenico Maggiore,

returned to teach theology in 1272. As well, the philosopher monk, Giordano

Bruno, lived here before setting off on his wanderings as an itinerant

teacher.The side of San Domenico Maggiore on the square is actually

the front of the church, meaning that if you go in that entrance you

come up next to the altar, itself. The main entrance, from the back,

opens onto a courtyard within the monastery, itself, and is generally

not open.

The present-day

form of the square took shape between the 15th and 19th centuries, starting

with work done by the Aragonese, who transformed it into one of the

most important centers in the city. Bounding the square are a number

of prominent buildings in the medieval and, later, Spanish history of

the city.

Next to the stairway on the left as you

face the church is Palazzo Balzo, now called Palazzo Petrucci

(photo on right). Its origins are in the early 14th century as a residence

of nobility connected with the move of the Angevin dynasty from Sicily

to Naples. It passed into the hands of Petrucci in the mid-1400s. Petrucci

enjoyed the favor of Ferrante, the Aragonese ruler of Naples, until

he joined the so-called "Barons' revolt" of 1485. He was executed by

decapitation. The building has changed hands many times since then,

and the only real remnant of the 14th century seems to be the main portal. Next to the stairway on the left as you

face the church is Palazzo Balzo, now called Palazzo Petrucci

(photo on right). Its origins are in the early 14th century as a residence

of nobility connected with the move of the Angevin dynasty from Sicily

to Naples. It passed into the hands of Petrucci in the mid-1400s. Petrucci

enjoyed the favor of Ferrante, the Aragonese ruler of Naples, until

he joined the so-called "Barons' revolt" of 1485. He was executed by

decapitation. The building has changed hands many times since then,

and the only real remnant of the 14th century seems to be the main portal.

On the other side of the square is the Palazzo

Sangro di Sansevero (photo on left), built in the middle of the

16th century. The Palazzo was built in the second half of the 1500s

at the behest of Paolo di Sangro. The simple facade was embellished

in 1621 and is the one we see today. Over the ornate portals is the

crest of the Sangro di Severo family. The most famous of the family

is Raimondo di Sangro, Prince of Sansevero

(1710-71), whose scientific and technological research earned him an

excommunication and reputation for sorcery. On the other side of the square is the Palazzo

Sangro di Sansevero (photo on left), built in the middle of the

16th century. The Palazzo was built in the second half of the 1500s

at the behest of Paolo di Sangro. The simple facade was embellished

in 1621 and is the one we see today. Over the ornate portals is the

crest of the Sangro di Severo family. The most famous of the family

is Raimondo di Sangro, Prince of Sansevero

(1710-71), whose scientific and technological research earned him an

excommunication and reputation for sorcery.

The building

is one of those in Naples said to be haunted! In 1590, prince Carlo

Gesualdo, famous composer of madrigals, killed his wife, Maria d’Avalos,

and her young lover, don Fabrizio Carafa. They say that Gesualdo then

killed his own tiny son because of a resemblance, real or imagined,

to his wife's lover. After the murders, Gesualdo went on to compose

some of the most beautiful and innovative pieces in the madrigal repertoire.

He married a second time and died in Naples in 1614. Tradition says

that the ghost of his murdered wife still walks the halls of the building.

The famous chapel of Sansevero is off the square in back of the

Palazzo, itself, and is more properly named the Chapel of Santa Maria

della Pietà, or Pietatella. It dates back to 1590 when the Sansevero

family had a private chapel built in what were then the gardens of the

nearby family residence, the Palazzo Sansevero. Definitive form was

given to the chapel by Raimondo di Sangro, famous Prince of Sansevero,

whose patronage added the frescos and sculpture, which would turn the

chapel into a harmonious and integral manifestation of religious faith

of the eighteenth century. Unique and world famous, of course, is the

statue of the Veiled Christ (photo on left), sculpted by Giuseppe

Sanmartino in 1753. The famous chapel of Sansevero is off the square in back of the

Palazzo, itself, and is more properly named the Chapel of Santa Maria

della Pietà, or Pietatella. It dates back to 1590 when the Sansevero

family had a private chapel built in what were then the gardens of the

nearby family residence, the Palazzo Sansevero. Definitive form was

given to the chapel by Raimondo di Sangro, famous Prince of Sansevero,

whose patronage added the frescos and sculpture, which would turn the

chapel into a harmonious and integral manifestation of religious faith

of the eighteenth century. Unique and world famous, of course, is the

statue of the Veiled Christ (photo on left), sculpted by Giuseppe

Sanmartino in 1753.

The Palazzo Sangro di Sansevero

is flanked by Palazzo Corigliano (photo on right), the building

on the corner of Spaccanapoli. Palazzo Corigliano got its name

in the 1700s from its most famous tenant, Duke Augustino di Corigliano,

but is much older than that. Construction started on Palazzo Corigliano

in 1506,at the very beginning of the Spanish viceroyship in Naples.

Sources from the 1600s and 1700s refer to it as one of the first truly

modern buildings in the city. Originally, the building had two stories,

but a third was added in the 1700s by the owner, Agostino Saluzzo. Almost

all of the sculpture and decorative murals within Palazzo Corigliano

stem from the 1730s. Spectacular and representative as they are of the

period, they are considered virtually in a class by themselves in Naples.

Quite recently, after extensive renovation, Palazzo Coriglno

has served to house some departments of the Orientale University of

Naples. The Palazzo Sangro di Sansevero

is flanked by Palazzo Corigliano (photo on right), the building

on the corner of Spaccanapoli. Palazzo Corigliano got its name

in the 1700s from its most famous tenant, Duke Augustino di Corigliano,

but is much older than that. Construction started on Palazzo Corigliano

in 1506,at the very beginning of the Spanish viceroyship in Naples.

Sources from the 1600s and 1700s refer to it as one of the first truly

modern buildings in the city. Originally, the building had two stories,

but a third was added in the 1700s by the owner, Agostino Saluzzo. Almost

all of the sculpture and decorative murals within Palazzo Corigliano

stem from the 1730s. Spectacular and representative as they are of the

period, they are considered virtually in a class by themselves in Naples.

Quite recently, after extensive renovation, Palazzo Coriglno

has served to house some departments of the Orientale University of

Naples.

The square

is closed on the south side by the Palazzo Casacalenda, an 18th century

building erected on the site of an ancient Greek temple, remnants of

which can be seen within the courtyard.

Wine

We

had a bottle of good wine some time ago right down on the water's edge

of Lake Averno, the place of the fabled

descent into the Inferno (from the name "Averno," by the way). Our host

told us that his vineyard and a few others down along the slopes of

the lake and in a few other places in Italy produced unusual wine for

this day and age in Europe; this is because they enjoy the same soil

characteristics (having to do with nearby volcanoes and other subterranean

goings-on). We

had a bottle of good wine some time ago right down on the water's edge

of Lake Averno, the place of the fabled

descent into the Inferno (from the name "Averno," by the way). Our host

told us that his vineyard and a few others down along the slopes of

the lake and in a few other places in Italy produced unusual wine for

this day and age in Europe; this is because they enjoy the same soil

characteristics (having to do with nearby volcanoes and other subterranean

goings-on).

Such locations

remained immune to the devastating winepest that spread though European

vineyards in the late 1800s. The disease was the result of the Phylloxera

aphid, which wiped out many European vineyards. As it turned out,

the roots of American vines were immune to Phylloxera, so European

wine makers grafted their vines onto American roots to make them less

vulnerable to the disease. That saved the European wine industry. But

down on Lake Averno, we had some good grape that had never had to be

revived. The gentleman showed us a vine that he claims is 250 years

old. It is a solid, almost tree-trunk-like affair as it comes out of

the ground and is the mother vine for the entire vineyard. I don't know

if "mother vine" is legitimate terminology. The Italian word is vitigno,

which they distinguish from the smaller, secondary vine—vite—that

runs through the vineyard and actually sprouts grapes. There seem to

be two words for "vineyard," as well: vigna and vigneto.

I don't think there is a difference.

I had not

set out to learn anything about Phylloxera. I started out looking

for strange names of wines, and, as usual, wandered away into a thicket

of miscellany. The most unusual name for a wine that I have ever heard

actually belongs to a German wine. It is called Croever Nacktarsch,

which is usually translated euphemistically as "bare bottom," but the

term in German is as vulgar as anyone who can read English might imagine

it to be. Croev is a town on the Middle Moselle between Zell and Traben

Trarbach in Germany. The label of the wine shows a small boy being spanked

on his bare behind by the inn-keeper, who has just caught the lad down

in the cellar doing some pre-pubescent wine tasting.

My

vote for the most amusing name for an Italian wine goes to Est! Est!

Est! —Latin for "This is it! This is it! This is it!" It seems

that in the year 1111, Henry V of England was on his way to Rome to

be crowned by the Pope. In his entourage was one Giovanni Deuc, a lover

of fine wine. Near Montefiascone (not far from Lake Bolsena, near Orvieto,

in central Italy), Giovanni sent his servant, Martin, ahead to scout

the potential for bibbing. The instructions were, "When you find the

good stuff, scrawl 'Est!' on the door of the tavern, so I know where

to stop." Marty was so impressed with one vintage that he waxed redundantly

enthusiastic and emblazoned "Est! Est! Est!" on the door. Giovanni

apparently drank himself to death right on the spot. He left money to

the town of Montefiascone to commemorate his fatal binge: every year,

a bottle of Est! Est! Est! is poured on his tomb, where there

is still the legible inscription: "From too much Est!, here lies

my lord, Giovanni Deuc." I hope that's a true story; anyone who would

make that up must have been drinking. My

vote for the most amusing name for an Italian wine goes to Est! Est!

Est! —Latin for "This is it! This is it! This is it!" It seems

that in the year 1111, Henry V of England was on his way to Rome to

be crowned by the Pope. In his entourage was one Giovanni Deuc, a lover

of fine wine. Near Montefiascone (not far from Lake Bolsena, near Orvieto,

in central Italy), Giovanni sent his servant, Martin, ahead to scout

the potential for bibbing. The instructions were, "When you find the

good stuff, scrawl 'Est!' on the door of the tavern, so I know where

to stop." Marty was so impressed with one vintage that he waxed redundantly

enthusiastic and emblazoned "Est! Est! Est!" on the door. Giovanni

apparently drank himself to death right on the spot. He left money to

the town of Montefiascone to commemorate his fatal binge: every year,

a bottle of Est! Est! Est! is poured on his tomb, where there

is still the legible inscription: "From too much Est!, here lies

my lord, Giovanni Deuc." I hope that's a true story; anyone who would

make that up must have been drinking.

In the

Naples area, the most interesting name for a wine is Lachryma Christi

(Tears of Christ). It is produced on the fertile slopes of Vesuvius,

and the wine is so named because it is here, they say, that Lucifer

was cast out of heaven, causing Christ to weep. The funniest name for

a local wine comes from Ischia, where they drink Pere 'e palummo,

dialect for "Foot of the dove," so called because the ruby-red color

of the stems of the vine recalls the coloring of that particular bird's

foot. A likely story? Maybe.

Dante, Piazza

Piazza Dante is a bit of welcome wide-open space in a city notoriously

lacking in elbow room. It was closed for a few years while they built

the new Metropolitana underground train station. Now that that is finished,

it was well worth the wait for two reasons: one, it's a place to sit

down or stroll around a bit in the middle of a busy city, and, two,

the square is now conveniently connected to the Vomero section of town

a few miles away and 600 feet higher in elevation. Piazza Dante is a bit of welcome wide-open space in a city notoriously

lacking in elbow room. It was closed for a few years while they built

the new Metropolitana underground train station. Now that that is finished,

it was well worth the wait for two reasons: one, it's a place to sit

down or stroll around a bit in the middle of a busy city, and, two,

the square is now conveniently connected to the Vomero section of town

a few miles away and 600 feet higher in elevation.

This square,

named for one of the greatest names in world literature, is dominated

by a 19th-century statue of the poet, sculpted by Tito Angelini. Long

ago the square was called Largo del Mercatello—simply,

Market Square—and, then, in 1765 was rechristened "Foro Carolina,"

after the wife of the King of Naples. At that time, the original square

was greatly modified by Luigi Vanvitelli. The ornate semicircular arrangement

of columns and statues was originally intended to depict the virtues

of Charles III, the first Bourbon king of Naples; the niche in the center

was to have been dedicated to the monarch. It now, however, marks the

entrance to a boarding-school named for Victor Emanuel II. Piazza Dante

was the site of the Cafe Diodato, a gathering place of actors at the

end of the 19th century, who, during the summer months would perform

on a stage set up amid the tables.

Facing

the great semicircular building, one sees Port'Alba on the left.

Port'Alba was an old city gate, moved in the 17th century by

the Spanish viceroy Duke d'Alba Antonio Alvarez de Toledo, and incorporated

into the restructured Foro Carolina. On the right is the Church of San

Michele, and across from the square is the Church of San Domenico Soriano

with its adjacent convent, now housing the municipal registry office.

Poor Dante

was moved 100 meters away in order to accommodate the construction of

the new station, but now he is back center-stage and sand-blasted clean

as a whistle.

Geology

(2), volcanoes (2)

Somehow I admire people who live in volcanoes or at

least on the slopes of volcanoes, even when they're extinct (the volcanoes,

not the people). Yesterday we had lunch in a delightful restaurant on

the inside slope of a crater, out in Baia, just past the bay of Pozzuoli.

It is at the end of the Campi Flegrei—the "Fiery Fields"—in

parts, a still active and bubbling collection of thermal baths and sulfur

fumaroles, but for the most part a welter of extinct craters some millions

of years old. (The famous Pozzuoli caldera, however, is only 35,000

years old, and the nearby "Monte Nuovo"—New

Mountain—really is new, as mountains go; it surfaced in the 1500s. Somehow I admire people who live in volcanoes or at

least on the slopes of volcanoes, even when they're extinct (the volcanoes,

not the people). Yesterday we had lunch in a delightful restaurant on

the inside slope of a crater, out in Baia, just past the bay of Pozzuoli.

It is at the end of the Campi Flegrei—the "Fiery Fields"—in

parts, a still active and bubbling collection of thermal baths and sulfur

fumaroles, but for the most part a welter of extinct craters some millions

of years old. (The famous Pozzuoli caldera, however, is only 35,000

years old, and the nearby "Monte Nuovo"—New

Mountain—really is new, as mountains go; it surfaced in the 1500s.

The restaurant

was a three-level affair clinging to the slope (photo), making up in

vertical space what it lacked in horizontal. From the terrace, you could

look across and see other optimists clinging to their bit of slope across

the way. You could look down and see a farmhouse at the bottom. It was

set in a nice stand of trees, and there was a small vineyard down there,

as well.

The residents

are not in any actual danger because the craters really are extinct.

On the other hand, on the eastern side of the city of Naples, Mt. Vesuvius

last erupted in 1944 and is now described as "quiescent". I think that

term describes a condition somewhat more threatening than "dormant".

I know that the Vesuvius Observatory updates their webpage on a daily

basis, reminding you of the number of "seismic events yesterday," for

example. Most of the "events" are not noticed by human senses, but sensors

indicate a significant amount of activity. They say there is a "plug"

building up about 6 miles below the crater. The real optimists are the

ones who built on that slope right after the eruption half a century ago and who continue to

build and lead their lives with complete, fatalistic disdain for what

the future might hold. Last year, the collective communities around

Vesuvius considered it important to have a practice evacuation of the

area. They chose, as I recall, 500 volunteers and said "Go!". The make-believe

refugees from a make-believe eruption then followed the planned evacuation

routes to safety. It went well. Evacuating almost a million people in

the real thing would be a different matter, I'm afraid. Perhaps the

only point for true optimism is that Vesuvius is one of the best monitored

volcanoes in the world. It is unlikely that there would be no warning

at all of an impending eruption.

[Click

here for a separate item on the "Geology of the Bay of Naples".]

Monuments

in May

This

weekend will mark the beginning of the "Monuments in May" festivities

in Naples. It's a month-long bath of culture, an attempt to open everything

in the city that can be opened—all the museums, churches, and

archaeological sites. The larger ones are usually open all year round,

but in May the city makes an extra effort to put the city's considerable

cultural wealth on display for tourists. This

weekend will mark the beginning of the "Monuments in May" festivities

in Naples. It's a month-long bath of culture, an attempt to open everything

in the city that can be opened—all the museums, churches, and

archaeological sites. The larger ones are usually open all year round,

but in May the city makes an extra effort to put the city's considerable

cultural wealth on display for tourists.

Many of

the sites are separated into "itineraries," broken down by centuries,

with maps and markers indicating that this or that church is part of

the "17th–century route," for example. The ancient archaeological

sites outside the city, such as Herculaneum and Pompeii, of course,

need no introduction; lesser known ones, such as Oplontis

(near Pompeii) and the excavated Roman market below the church of San Lorenzo at the crossroads of the historic center

of the Naples, itself, can expect tourist traffic much heavier than

usual. Unusual sites—the Bourbon Poorhouse, for example—what was to

be a self-contained and self-sustaining institution for the indigent

in the 17th and 18th centuries, and is today a five-story, 300-meter-long

white elephant dozing in the sun at Piazza Carlo III—will also

be open. This is the month you can get in to walk through the ancient

Seiano tunnel beneath Posillipo from

the Bagnoli entrance all the way through and up onto some wealthy gentleman's

private property on the Posillipo side, which features the ruins of

a Greek amphitheater that, 2,000 years ago, belonged to Vedius Pollio,

a wealthy Roman gentleman in his own right.

The papers

are already complaining about the confusion. A reporter from Il Mattino

claims he stood in beautiful wide-open Piazza Plebiscito in front of the Royal Palace for

one hour and counted 119 motor-scooters racing across and around the

square, nominally a pedestrian zone. The front page featured a photo

of one young thug, reared up on the back wheel of his bike and doing

a "wheelie" across the square. Not a cop in sight, said the paper. Piano

wire stretched at neck level might help make up for the city's lack

of commitment to make Naples more visitable. The reporter didn't say

that; that's just a friendly suggestion.

Pulcinella

On a wall in the Cave

of Les Trois Ariège in France there is a stone-age drawing of

a sorcerer wearing a mask. From his time to ours, from him to our own

children modestly disguised for Halloween, or revelers made up for carnevale,

there is an unbroken chain of masks. Made of every and anything from

mud to gold, they have served to frighten, delight, beg, accompany the

dead, cast out demons, and conceal lovers and executioners. From Greek

drama to Balinese trance-dancers to modern psychodrama in which actors

wear masks of their own faces, in every culture and in all of history,

there have been masks. On a wall in the Cave

of Les Trois Ariège in France there is a stone-age drawing of

a sorcerer wearing a mask. From his time to ours, from him to our own

children modestly disguised for Halloween, or revelers made up for carnevale,

there is an unbroken chain of masks. Made of every and anything from

mud to gold, they have served to frighten, delight, beg, accompany the

dead, cast out demons, and conceal lovers and executioners. From Greek

drama to Balinese trance-dancers to modern psychodrama in which actors

wear masks of their own faces, in every culture and in all of history,

there have been masks.

The mask

took on new meaning at the end of the 16th century in Italy, when there

arose a form of theatre known as the Commedia dell'Arte. The

actors were skilled in the representation of well-defined characters,

characters who appeared and reappeared, bearing the same name, wearing

the same mask and costume, speaking the same language and, thus, establishing

themselves as distinct character types, stereotypes of various regions

througout Italy. For example, the stereotypical mask of Bologna is the

pseudo-intellectual windbag, Dr. Balanzone, and Venice gives us the

greedy and conniving underling, Arlecchino.

One of

the best-known Italian masks is the one that represents Naples, Pulcinella.

He is generally presented as a hunchback (remember that male hunchbacks

are considered lucky in Naples!); he is dressed in a large, white smock

and soft white hat, and wears a black half-mask characterized by a hook-nose.

His character type is that of the jolly bungler, always poor and hungry,

yet always able to get by, singing songs and playing the mandolin.

In his stereotypical ineptness, however, there always remains the touch

of the true court jester, the "fool," who delights in snubbing his nose

at the powers that be, without their ever really catching on to how

much wisdom is hidden behind the mask.

It is that

anti–establishment part of Pulcinella's personality, the total

disrespect of authority that seems to be not so hidden in much modern-day

Neapolitan behavior. That's the reason—say some—that Neapolitans

drive they way they do. The state put that traffic light on the corner,

telling you when to go and when to stop. A free citizen is almost honor–bound

to ignore it.

San

Martino, Sant'Elmo

Seen

from the sea, the most visible structures in Naples are the museum of

San Martino and the fortress of Sant' Elmo, located on the Vomero hill

at the highest point in the city. The museum used to be a monastery

that was finished and inaugurated under the rule of Queen Giovanna I

in 1368. It was dedicated to St. Martin, bishop of Tours. During

the first half of the sixteenth century, propelled by the energies of

the Counterreformation, it was expanded. Later, in 1623, it was further

expanded and became, under the direction of architect Cosimo Fanzago,

the quintessentially Baroque structure one sees today. Fanzago was responsible

also for the small cemetery in the courtyard; a cemetery ornamented

by rows of skulls, a typical Counterreformation memento

mori—a reminder of mortality. Seen

from the sea, the most visible structures in Naples are the museum of

San Martino and the fortress of Sant' Elmo, located on the Vomero hill

at the highest point in the city. The museum used to be a monastery

that was finished and inaugurated under the rule of Queen Giovanna I

in 1368. It was dedicated to St. Martin, bishop of Tours. During

the first half of the sixteenth century, propelled by the energies of

the Counterreformation, it was expanded. Later, in 1623, it was further

expanded and became, under the direction of architect Cosimo Fanzago,

the quintessentially Baroque structure one sees today. Fanzago was responsible

also for the small cemetery in the courtyard; a cemetery ornamented

by rows of skulls, a typical Counterreformation memento

mori—a reminder of mortality.

Under the

French, the monastery was closed in 1806

and was abandoned by the religious order. Today, the museum houses a

museum with a fine display of Spanish and Bourbon

era artifacts, as well as a recently restored presepe, or Nativity

scene, a display made up of thousands of finely wrought eighteenth-century

Christmas figures. It is the finest display of its kind in the world.

(Click here for more about the presepe.)

Sant’

Elmo is the name of both the hill and the fortress adjacent to the museum.

The name is from an old church, Sant’ Erasmo, that name being

shortened to "Ermo" and, finally, "Elmo".* The fortress was first started

in 1329 under Robert of Anjou and completed in 1343, the year of his

death. The strategic importance of the fortress was clear, and

the Spanish viceroy, Don Pedro de Toledo, had it rebuilt between 1537

and 1546. It was partially destroyed in 1587 when a lightning strike

caused the ammuntion dump to explode, killing 150 men in the process.

During the revolution of 1647, so-called “Masaniello’s

Revolt,” the Spanish viceroy took refuge in the fortress to

escape the revolutionaries. The people stormed the fortress but failed

to take it.

Sant’Elmo

was a dramatic symbol of the short, turbulent period of the Parthenopean

Republic, the local version of the French Republic. The fortress was

taken by the populace in 1799 and the Republic was proclaimed. A few

months later, the revolutionaries were forced to capitulate to Royalist

forces under Cardinal Ruffo. For a short

period, Sant’Elmo had been a bastion of freedom against Bourbon

absolutism; now it proved to be the prison and place of execution for

a number of the Republic’s supporters.

[*I

gratefully acknowledge some etymological information I have received

from Libero Scinicariello of Cleveland, Ohio: "... just a few miles

up the road in Gaeta, Erasmo is the patron saint and the namesake for

the Duomo. In local dialect, Erasmo evolved into Raimo, and the

church is referred to as Santu Raimo."]

Customs,

new & old; San Gennaro (3), Mark Twain

In The

Innocents Abroad, Mark Twain ridicules the miracle of San Gennaro

(click here to read the entire

excerpt) —that is, the miraculous liquefaction of the blood of

San Gennaro—as "…one of the wretchedest

of all the religious impostures one can find in Italy". One of the two

days on which that miracle is believed to occur is coming up: the first

Sunday in May. I don't pass judgment on miracles or others' belief in

such. If I did, I would find a real job somewhere as a Miracle Judgment

Passer or something like that.

Twain also

mentions another, rather curious, custom that I have enquired about

but been unable to shed any light on. He says:

| And

here, also, they used to have a grand procession, of priests,

citizens, soldiers, sailors, and the high dignitaries of the City

Government, once a year, to shave the head of a made up Madonna

– a stuffed and painted image, like a milliner’s dummy—whose

hair miraculously grew and restored itself every twelve months.

They still kept up this shaving procession as late as four or

five years ago. |

That would

make it about 1865. I have asked, and no one seems to know anything

about it. Maybe they made up the story to feed his cynicism. Customs

come and go, so I suppose it is quite possible that that one really

did exist and simply fell by the wayside. There are also recent customs

that probably seem ancient to young children, but the origins of which

are within living memory. Another

entry mentions the "Wishing Tree," a Christmas tree set up in the

center of the Galleria Umberto in December; you scrawl your wish for

the coming year on a slip of paper and stick it on one of the branches.

The custom of Christmas trees didn't find its way into this part of

Italy until after WW2, so that would be an example of a recent custom.

It is also an interesting example of combining something new—the

tree—with something old—the votive slips of paper, which

can show up at almost any religious shrine in Naples and even on some

non-Christian statuary, such as the statue of the Nile God in the historic center of

the city.

This morning

I noticed that someone is trying to invent a new custom. I was down

at the Gambrinus Café off of Piazza Plebiscito, and I

noticed a picture of Mt. Vesuvius on the wall. So far, nothing out of

the ordinary. Below the picture, however, was a written invitation to

"make your wish to Vesuvius" and to deposit the slip in the box provided

on the table next to the picture. Making a wish to Vesuvius? That is

unheard of, I believe, until invented by the proprietor of the café

as some sort of a commercial gimmick. I have never heard of any custom

that involves invoking the great god of the volcano (or some such Polynesia-like

deity) in Naples. As far as I know, they don't sacrifice goats or virgins

up there, either, both of which are in short supply in the area, anyway.

Maybe in a few years, it will be a custom. Like old proverbs—someone

has to come up with these things.

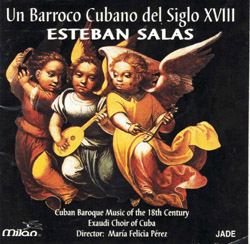

Salas,

Esteban; music (5)

One

of the most unusual references to Neapolitan music that I have ever

come across was in a music catalogue; there was a short blurb

for a CD of music by Esteban Salas, "a composer of the Cuban-Neapolitan

Baroque". That, of course, piqued my interest. Who could have ever imagined

such a thing as a Cuban-Neapolitan Baroque connection? (Actually, with

a bit of reflection, it isn't at all bizarre: Cuba and Naples were both

part of the same Spanish Empire.) I sent away for the item and am very

happy that I did so. It is called Esteban Salas, Cuban Baroque Music

of the XVIII Century and is a recording from 1995, a collection

of the composer's Christmas carols performed by the Exaudi Choir of

Cuba. The music is beautiful—so delightful and effortlessly innocent

that it just seems to sing itself. It is one of the unfortunate quirks

of history that Salas is obscure today. One

of the most unusual references to Neapolitan music that I have ever

come across was in a music catalogue; there was a short blurb

for a CD of music by Esteban Salas, "a composer of the Cuban-Neapolitan

Baroque". That, of course, piqued my interest. Who could have ever imagined

such a thing as a Cuban-Neapolitan Baroque connection? (Actually, with

a bit of reflection, it isn't at all bizarre: Cuba and Naples were both

part of the same Spanish Empire.) I sent away for the item and am very

happy that I did so. It is called Esteban Salas, Cuban Baroque Music

of the XVIII Century and is a recording from 1995, a collection

of the composer's Christmas carols performed by the Exaudi Choir of

Cuba. The music is beautiful—so delightful and effortlessly innocent

that it just seems to sing itself. It is one of the unfortunate quirks

of history that Salas is obscure today.

Esteban

Salas y Castro was born in Havana on Christmas Day in 1725 and died

in Santiago de Cuba in 1803. He parents were natives of the Canary Islands

and, thus, musicologists list Salas as one of the first important native

composers of the New World. He started the study of music at age 11

and by the end of his long career had composed hundreds of liturgical

pieces. He also taught philosophy and theology.

The Neapolitan

connection, mentioned above, comes from the fact that Cuba—the

"Pearl Beyond the Sea"—and the Kingdom of Naples were both part

of the Spanish Empire. The Spanish ruled Naples as a vicerealm from

1500 to 1700 and are responsible for establishing the important music conservatories in Naples in the mid-1500s. It

is logical that the Spanish exported their culture to the rest of the

empire, as well—a music school in Havana, for example. (Now that

I pursue this line of thought, perhaps they established such schools

even in the Philippines. That is something I shall have to find out).

This, then,

from the liner notes of the CD:

| …We know nothing of his masters, nor

how he acquired

all the refinements of his art. It is possible that a certain Cayetano

Pagueras of Barcelona, a seafarer but also a good musician and singer,

had passed on to Salas the astonishing technique apparent throughout

his

compositions. In 1750 he had sailed from Spain to Cuba…He may have

furnished

Salas with scores…accessible to musicians in Spain at that period:

those

by Porpora, Paisiello, Alessandro Scarlatti and other 18th century

Neapolitan

masters (for Naples then belonged to Spain), notably those by Francesco

Durante, the harmonies and styles of which are present in those of

Salas… |

|