©

2004 Jeff Matthews & napoli.com

Fra

Diavolo

It

is not as easy to find information on Fra Diavolo as one might think.

He was a bandit, a brigand—anything from Robin Hood to Al Capone,

depending on the source of your information-- active in the Bourbon

defeat of the Neapolitan Republic in 1799. It

is not as easy to find information on Fra Diavolo as one might think.

He was a bandit, a brigand—anything from Robin Hood to Al Capone,

depending on the source of your information-- active in the Bourbon

defeat of the Neapolitan Republic in 1799.

First,

however, there is much more information available on something called

Shrimp Fra Diavolo. I found a recipe that serves 6. I should use medium-size

(36-to 40-count) shrimp. If I can't find peeled raw shrimp, I can substitute

peeled cooked shrimp. I may try it. Then, again, I may not.

Also, a

bit higher—but not much—on my Fra Diavolo list is the 3-act

opera of that name by the French composer, Daniel François Aubert

(1782-1871). It was composed in 1830. It turns out that Aubert also

composed an opera entitled Masaniello, who was a Neapolitan revolutionary

from the 1600s. (You have probably never heard that one, either, but

if you want to read about Masaniello, click

here.)

And very

high on my list is the great 1933 Laurel and Hardy film, The Devil's

Brother-- or-- Fra Diavolo. I suppose that was my first encounter

with Southern Italian brigandage, although I didn't appreciate that

fact at the time. (My second encounter was getting mugged in the back

streets of Naples, but that is a story for another time.)

The real

Fra Diavolo was born Michele Pezza in the late 1770s in Itri, not far

from Gaeta about 60 miles north of Naples. In 1797 he fled his town

to avoid prosecution for having murdered his employer in a squabble.

He took up the life of the bandit. He was, then, one of the first to

answer King Ferdinand's call for aid from such outlaws to help retake

the kingdom of Naples from the revolutionary government of the Neapolitan

Republic, which had successfully sent the Bourbon monarchy packing

to Sicily in 1799. He went to Sicily where he was well received

by the King and Queen. He was made a Captain in the Bourbon army and

returned north where he landed his force of 400 men near Gaeta. He spent

the next 6 months harassing the Republican forces and the French troops

supporting them. He and his men conducted themselves with such savagery

that Cardinal Ruffo, the leader of the royalist Army of

the Holy Faith, forbade them from entering centers of large population

for fear of the butchery that might ensue.

Fra Diavolo

--"Brother devil"-- was so-called apparently because he had expressed

a wish as a young man to enter the clergy and on a few occasions

disguised himself as a monk. He was instrumental --with other brigands

like him-- in the Bourbon reconquest of the Kingdom of Naples and helped

pursue the retreating French forces back to Rome where that city, too,

eventually fell with the collapse of the so-called "Roman Republic".

Five years

of peace then ensued between France and the Kingdom of Naples. Fra Diavolo

enjoyed the relaxing life of the ex-bandit celebrity, now the newly

declared Duke of Cassano and loyal servant of his king. He would need

the respite, however, for in 1806 Napoleon Bonaparte brought his considerable

military prowess to bear on the Bourbons of Naples. The French invaded

the kingdom and, once again, the Bourbons fled to Sicily, protected

by the British fleet. Queen Caroline's plan was as clear as it was futile:

retake the kingdom again, the same way they had done before. Cardinal

Ruffo was called upon, again, to form another army. He would have no

part of it this time, saying that "a man is good for only one such effort

in a lifetime".

Fra Diavolo,

however, answered the call, as did numerous other ex-outlaws of the

day. It is moot whether they were motivated by money (they were mercenaries),

or by loyalty to their king, or by fear of eventually all being conscripted

into the French army and sent off to fight Bonaparte's wars elsewhere

in Europe. In any event, Napoleon sent his brother, Joseph, to

Naples as the king. At the top of the list of things to do was cleanse

the kingdom of brigandage. Joseph sent out Colonel Hugo (the father

of the author, Victor Hugo) to hunt down the most wanted bandit of them

all, Fra Diavolo.

It was

only a matter of time, but in the autumn of 1806 Fra Diavolo, with a

strong force of 1500 men -- but still outnumbered-- went back into the

mountains to lead a short-lived and ferocious game of hit-and-run warfare

with the regular army. At the end he was reduced to the tactic of every-man-for-himself,

telling his remaining men to meet him in Sicily, where they would regroup.

That was not to be. He was captured alone and exhausted in a tavern

in the village of Baronissi, not far from Salerno. He was taken to Naples

and sentenced to death in spite of an appeal for clemency brought on

his behalf by his nemesis, Colonel Hugo.

The King,

however, had his own orders from his brother, Napoleon. Fra Diavolo

was executed by hanging in Piazza Mercato

in Naples on November 11, 1806. He apparently went stoically to his

death. He wore his Bourbon military uniform.

There is

no report that he asked for Shrimp Fra Diavolo as a last meal.

earthquakes

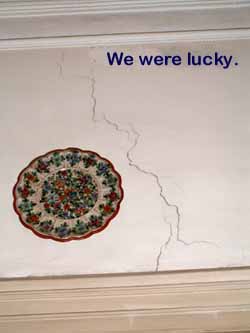

There

was a sharp earthquake near the city of Campobasso yesterday. Naples

is close enough for such a tremor to be felt. I didn't feel it, but

I was out walking around in the city, where the normal rumblings of

passing traffic might make it difficult to tell. Others, however, tell

me they felt the quake quite perceptibly --or, at least, "saw" it in

the form of chandeliers moving slightly. Those working high up in the

skyscrapers of the new Civic Center on the eastern side of the city

really noticed it, however. Offices and schools were evacuated successfully. There

was a sharp earthquake near the city of Campobasso yesterday. Naples

is close enough for such a tremor to be felt. I didn't feel it, but

I was out walking around in the city, where the normal rumblings of

passing traffic might make it difficult to tell. Others, however, tell

me they felt the quake quite perceptibly --or, at least, "saw" it in

the form of chandeliers moving slightly. Those working high up in the

skyscrapers of the new Civic Center on the eastern side of the city

really noticed it, however. Offices and schools were evacuated successfully.

Italians

are more used to the Mercalli scale for measuring quakes. Unlike the

Richter scale, which measures the magnitude of an earthquake in terms

of actual amount of energy released, the Mercalli scale is a description

of perceived effect on the environment. The quake yesterday measured

5.4 on the Richter scale and 8 on the Mercalli scale, some of the parameters

of which are:

| General

fright. Alarm approaches panic. Sand and mud erupts in small amounts.

Damage slight in brick structures built especially to withstand

earthquakes, but considerable in ordinary substantial buildings,

with some partial collapse. Wet ground and steep slopes crack

to some extent. Walls fall. Solid stone walls crack and break

seriously. Chimneys, columns and factory towers twist and fall.

Very heavy furniture moves conspicuously and overturns. |

Indeed,

a school collapsed in the village most directly affected by the quake,

San Giuliano di Puglia, where, as of this morning, 12 have died and

another 15 are still missing -- most of them children.

The only

time I have ever truly and solidly felt a quake here was the big one

in 1980. There was no doubt about that one. The entire building I was

in swayed for many seconds as the intensity built and then gradually

faded. The panic in the neighborhood was almost total. The epicenter

was many miles away from Naples and there the damage and loss of life

was considerable. In the city of Naples, itself, there was little severe

damage. Some people were hurt in the panic by, for example, falling

as they tried to run downstairs to get out of buildings. My mother-in-law

was in a lift and got the scare of her life as the lift shook and banged

against the sides of the shaft.

So, people

around here are getting a little jumpy. What with Etna erupting for

the last few days a few hundred miles to the south on Sicily --and,

then, a sharp quake there during the eruption -- people around here

just stare over at Vesuvius and wonder and wait. They had a practice

evacuation about a year ago in the area that would be immediately affected

by an eruption of Vesuvius. It went very well: about 500 volunteer subjects

were evacuated along designated escape routes. No problems. The difference

between such a drill, however, and the real thing cannot be overstated.

The area near Mt. Vesuvius is the most populated area in Europe. It

is difficult to imagine hundreds of thousands of inhabitants calmly

moving along assigned routes to safety.

--------

(Later: 4. 14 p.m.) Even as I write, there has just been another quake.

I felt this one since I am sitting in my flat on the 4th floor. The

vibrations come up strongly through the building and the height accentuates

the sway. The chandeliers danced around very nervously, as well. The

television broke in with a bulletin that the epicenter is about in the

same place as the one yesterday, meaning the same long-suffering villagers

are getting hammered again. There are no immediate reports as

to victims, but the television now reports that, grotesquely, the quake

struck during a memorial service for the children who died in yesterday's

quake.

(There

is a separate entry about the geology of the Bay of Naples. Click

here.)

Death,

culture of (1)

| A

memento mori stylized skull on the premises

of the Purgatorio del Arco |

Yesterday

was All Souls' Day, when many Roman Catholics remember their departed

loved ones. In Naples, this is an important day and one that many families

spend entirely at the cemetery, placing flowers and, in general, just

"hanging out".

Though

it is not necessarily a melancholy occasion, it does reflect the somewhat

obsessive relationship that Neapolitans have with this last great rite

of passage. There is no pretense at all --as there is, elsewhere-- of

being a "death-defying" culture, one in which public markers of grief

such as black armbands and graveside visits are avoided. Such reminders

are unselfconsciously everywhere. And one has only to walk into some

of the older churches in town to find ornate examples of the so-called

"memento mori" (Latin for "remember that you must

die); typically, these are stylized carvings of human skulls. The Museum

of San Martino (an ex-monastery) has a courtyard lined with them, and

the Church of Purgatorio del Arco features them prominently on

the façade. If carvings are not enough, there are crypts and

catacombs where you can see the real thing. (The photo, below, is of

a hypogeum, an undergound altar

or vault, in the cellar of the Church of Purgatorio del Arco.

It is bizzarely draped rather with an eclectic, almost vodoo-like array

of items.)

Yet, in spite

of this commitment to the traditional and totally serious view of death,

there is some bizarre competition never far below the surface. At least

that is my impression when I read in the local papers of two undertakers

getting into a fist-fight on the street over which one of them is going

to take custody of the deceased. The two them are waiting outside the

church for the funeral service to end, each one apparently under the

impression that he has the exclusive right to take the coffin to the

cemetery. Then, they start to haggle and push and shove each other in

an attempt to wrest the Dearly Departed into their respective hearses

--all this in the presence of mourners, who actually take time out from

their grief to get their licks in on one side or the other. Yet, in spite

of this commitment to the traditional and totally serious view of death,

there is some bizarre competition never far below the surface. At least

that is my impression when I read in the local papers of two undertakers

getting into a fist-fight on the street over which one of them is going

to take custody of the deceased. The two them are waiting outside the

church for the funeral service to end, each one apparently under the

impression that he has the exclusive right to take the coffin to the

cemetery. Then, they start to haggle and push and shove each other in

an attempt to wrest the Dearly Departed into their respective hearses

--all this in the presence of mourners, who actually take time out from

their grief to get their licks in on one side or the other.

In Naples

it is still possible to see large coach/hearses --huge glass and gold

affairs from another century-- drawn by as many as eight horses. Some

people save their money so they can blow it all on going out in style,

keeping the "bella figura" --a strange phrase meaning anything from

"looking good" to "keeping up a front"-- keeping that "bella figura"

right to the end --indeed, well past the end. I once saw one of these

coaches trying to turn into a small side street of the Spanish Quarter

off the main thoroughfare, via Toledo, downtown. These side streets

are narrow, generally congested and not amenable to passage by anything

less maneuverable than an anorexic bicycle; yet, the coachman turned

in, on his way to a church where a service was being held, so he could

give that last big important ride to someone who had saved up a small

fortune over many years just for this special occasion. As the horses

ably swung into their tight turn, one of the extravagant gilt curlicues

sticking out from the coach snagged on the roof of a small, prefabricated

newsstand. The vendor had set it up without too much regard for whether

or not he might be a bit too close to the corner of the sidestreet.

The coach tore the roof of the newsstand off and the noise startled

the horses, which then bolted up the alley, dragging half of this poor

man's business behind them all the way to the church.

The large

main cemetery in Naples is worth a visit if only to see the bizarre

ends which some people go to in order to cement themselves in place

for posterity --enormous tombs, pharoahonically silly ones, encrusted

with enough kitsch ornamentation to land you in whatever part of the

afterlife is reserved for good people with bad taste.

The strangest

thing I have seen so far at the cemetery is the "flower people". They

earn a pretty good living by prowling around the crypts waiting for

funeral processions to arrive. Generally, at around the same time, a

flower truck will roll up and unload onto the ground near the burial

site or tomb all the flowers that people have ordered for the service.

A good funeral will wind up with dozens of floral wreaths and displays,

representing a considerable amount of money. If, however, you want to

grab the flowers that you ordered and place them where you want at the

service, you must be there the second the flowers are unloaded, or you

will never get them. The minute the flowers hit the ground, they are

overrun by the "flower people". They will make off with everything in

a matter of seconds --and even get in some heated discussions of the

"Hey, I saw those first" type. No fisticuffs, however; you don't want

to damage the flowers. The flower people take their booty, all still

fresh and beautiful, back outside the cemetery to the main gate and

sell them to mourners who are on their way in.

Their view

is, I suppose, "So what's the big deal? It's only death." And it's even

good for a laugh, sometimes. Maybe that's not so bad.

Neapolitan

Song (2)

Some

years ago, the mayor of Venice, in a fit of high doge dudgeon, officially

declared that the gondoliers plying the city's watery by-ways should

stop serenading the tourists with Neapolitan Songs! Two questions may

occur to you. One: Why should he care? Two: What are Venetian boatsmen

doing singing 'O sole mio, in the first place? Well, one: He

cares for reasons of authenticity. Uninformed tourists may feel that

it is completely natural to go punting along the Grand Canal while their

chauffeur croons about returning to Sorrento, but the mayor knows better.

He knows that's as authentic as a Cockney waxing elegiac about the Bonnie

Banks of Loch Lomond or a Mississippi Delta blues singer belting out

a New England sea chantey. Two: The gondoliers sing these songs because

that's what the tourists want to hear. To them, Funiculì Funiculà,

Santa Lucia and other examples of la canzone napoletana,

the Neapolitan Song, are Italy. But they're not, really. They're Naples. Some

years ago, the mayor of Venice, in a fit of high doge dudgeon, officially

declared that the gondoliers plying the city's watery by-ways should

stop serenading the tourists with Neapolitan Songs! Two questions may

occur to you. One: Why should he care? Two: What are Venetian boatsmen

doing singing 'O sole mio, in the first place? Well, one: He

cares for reasons of authenticity. Uninformed tourists may feel that

it is completely natural to go punting along the Grand Canal while their

chauffeur croons about returning to Sorrento, but the mayor knows better.

He knows that's as authentic as a Cockney waxing elegiac about the Bonnie

Banks of Loch Lomond or a Mississippi Delta blues singer belting out

a New England sea chantey. Two: The gondoliers sing these songs because

that's what the tourists want to hear. To them, Funiculì Funiculà,

Santa Lucia and other examples of la canzone napoletana,

the Neapolitan Song, are Italy. But they're not, really. They're Naples.

Strictly

speaking, the Neapolitan Song is not folk-music, if by that term you

mean the result of countless ancient improvisations and reworkings handed

down from generation to generation of nameless troubadour. It is folk-music—in

spite of being formally composed and published—if you mean that

therein reflected is the ebullience, melancholy, joy, fatalism and thousand

emotions that Neapolitan character is heir to.

There are,

indeed, fragments of popular motifs which can be traced back half a

millennium, but the popular canzone napoletana, the sound which

conjures up "Italy" in the minds of millions the world over, dates back,

as a genre, to the first Festival of Piedigrotta,

held in 1835 and more or less regularly until shortly after WW II. Each

year, an official song of the festival was chosen and the winning song

from that very first year, Te voglio bene assaje, is still enormously

popular. It's about love, as you might imagine, but it is well worth

noting that the real passion in the Neapolitan Song is generally reserved

for celebrating the city, the sun and the sea-- or lamenting life's

greatest tragedy: not death, but, rather, being far from home. (The

meoldy to Te voglio bene assaje is usually attributed to Gaetano Donizetti.)

The Golden

Age of la canzone napoletana was around the turn of the century

and many of the best-loved songs found their way abroad on the lips

of the millions of emigrants who left their home. Many of them were

from Naples, which explains—along with the infectious charm of

the music, itself—why it was this music that became synonymous

with Italy all over the world. The great Italian tenor, Enrico

Caruso, was from Naples, and in America, besides his normal operatic

repertoire, he recorded many of these songs for RCA and even sang them

frequently as encores after a performance at the Metropolitan Opera

in New York.

But, whether

you're singing an exuberant tarantella or bewailing your lost homeland

in the immigrant tear-jerker, Lacreme napulitane, you have to

sing correctly--that is, in the Neapolitan

dialect. This means that "Napoli" becomes "Napule"

and "Sorrento""Surriento". And don't forget the retroflex "l"

and reduced final vowels. Even another great Italian tenor, Luciano

Pavarotti, evokes a good-natured wince or two down in these parts when

he wraps his Northern vowel sounds around 'O sole mio.

There are

a few bizarre sidelights to this phenomenon of the Neapolitan Song:

the pseudo-Neapolitan Song generated abroad, for example. Some years

ago, one Dino Crocetti (aka Dean Martin) unleashed a monstrosity called

That's Amore. Don't fail to miss that immortal first line: "When

the moon hits your eye like a big pizza pie, that's amore." Another

line contains perhaps the most execrable rhyme ever penned: "drool /fasule

" (Neapolitan for fagioli—beans). True to the prediction

implicit in H.L. Mencken's jibe that no one ever went broke underestimating

the taste of the American public, Dino had a smash hit on his hands.

Oh, well. Another "oh, well" for Elvis Presley and the lyric, "It's

now or never," sung to the melody of 'O sole mio. It is

not clear whether this version confused or amused the ultimate arbiters

of the canzone napoletana, the Neapolitans, themselves. Who knows?

One of them, Eduardo di Capua (1864-1917), the composer of 'O sole

mio, might even have been delighted, just as he undoubtedly is when

he looks down and sees men rowing legions of Americans, British, Japanese

and Germans along the lagoon beneath the cold and grey skies of Venice

and praising to them the glorious sun of Naples -- for, yes, the mayor

of Venice finally had to give in. Ha!

(Also see

here for another note on "That's Amore". In spite of my utterly

snobbish disdain for the song, I have to admit that Neapolitans love

it. Since there are no Italian or Neapolitan lyrics, they get a

kick out of singing it in the English version and trying to reproduce

a typical American accent. It's fun, or so they tell me.)

[You

may read the texts of some Neapolitan songs in the original Neapolitan

dialect by clicking here. Also, there are separate items

in the Naples Web Log on Funiculì-Funiculà

and 'o sole mio .]

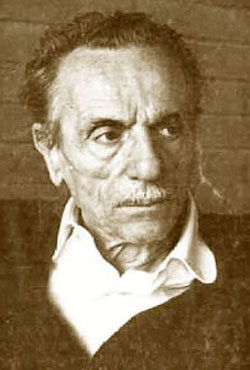

De Filippo,

Eduardo (1900-84) (1)

It happened

to me again the other day: another Eduardo-type situation. I

was sitting in my car, double-parked at the Naples airport. I was in

a line of about 25 cars, equally double-parked and each one of us equally

guilty of impeding traffic as it ploughed its dharma-like furrows of

turn and return past the entrance, out to the parking lot and back around

to the entrance. A traffic cop walked over to me and the following conversation

ensued: It happened

to me again the other day: another Eduardo-type situation. I

was sitting in my car, double-parked at the Naples airport. I was in

a line of about 25 cars, equally double-parked and each one of us equally

guilty of impeding traffic as it ploughed its dharma-like furrows of

turn and return past the entrance, out to the parking lot and back around

to the entrance. A traffic cop walked over to me and the following conversation

ensued:

"Hey,

you'll have to move your car, You're blocki—"

"You

know, of all these double-parked cars —and you'll notice that

traffic is still managing to squeeze by us— I am the only…"

"Look,

this is my job. People double-park, I tell them to move."

"…only

person who has stayed in his car while waiting, so I can move it to

let cars on the inside get out if they have to."

"OK.

Have it your way." (Exit traffic gendarme.)

Authority,

Confrontation, Understanding, Resolution, and even a good-natured

Victory of sorts on behalf of the downtrodden, all in quick succession!

If this were the stage, I don't know if it would be Absurd or Realist

or What. How does one describe this Naples and its citizens? —

a hodge-podge of humour and despair, ordinary persons besieged by life,

thwarted, vexed, stepped on, yet maintaining the all-important "figura"

of self-respect and dignity, like Laurels and Hardys struggling through

Thoreau's "lives of quiet desperation"!

Eduardo

De Filippo does describe it, however, and it is why he is one

of the best-loved and best-known Italian playwrights of the century.

"Eduardo" (Italians, affectionately, are on a first-name basis with

their great artists), can be as bewildering as the Absurd, yet as political

and 'socially relevant' as Shaw or Brecht.

He started

as an actor with Neapolitan troupes in the 1920s, then with other members

of his family founded the "Compagnia del teatro Umoristico

i De Filippo," which he reformed as his own "Il Teatro di Eduardo"

in 1944. Many of his works are in the rich Neapolitan dialect and share

a number of recognizable 'Eduardian' themes, such as the struggle of

the down-and-out to retain dignity; the preservation of traditional

family values; moral deterioration in the face of poverty; and the injustice

of being forced to live beyond the law. Later in his career, he turned

somewhat away from dialect in a search to express themes which, though

they may be eternal, have become more evidently so in the twentieth

century —the need for illusion, for example. In this, his works

recall those of another great Italian playwright of our times, Luigi

Pirandello.

His works

are widely translated and a few have been made into films. Anyone who

has seen Marriage, Italian Style, starring Sofia Loren and Marcello

Mastroiani, has seen the film version of Eduardo's play Filumena

Marturano, the story of an ingenious ex-prostitute who gets her

common-law husband to marry her by revealing to him that he is the father

of one of her three sons. To ensure that he treats all three equally,

she refuses to tell him which one it is. The audience never finds out,

either, and to the end of his life, Eduardo good-naturedly complained

about all the letters he received from people begging to know which

one was the real son! Of course, they missed the point.

Eduardo

is still acknowledged to be the greatest interpreter of Eduard. Since

his death, Neapolitans have had to adjust to others playing all those

roles that he created for himself and that still seem to 'belong' to

him.

In the

long, long history of Naples, Eduardo, obviously, is very recent. Yet,

he so sums up this city that if a science-fiction device could present

his plays to past generations of Neapolitans, it is a sure bet that

they would nod their heads in assent, then sigh and wonder how they

had ever got along without him.

(I am

indebted to Michael Campo of Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut,

for conversations and information about Eduardo de Filippo.)

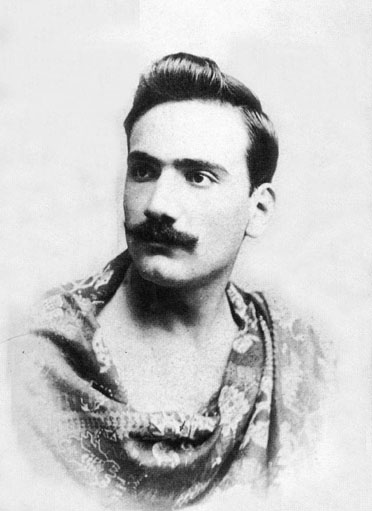

Caruso,

Enrico (2)

| Caruso

had a knack for sketching caricature. This is one he drew of himself.

|

I've

been reading a bit about Saverio Procida. He was a well-known Neapolitan

journalist and critic who passed away in 1940 after a 50-year career

dedicated primarily to literature and music. He was in the forefront

of those who welcomed to Italy the new and difficult music of Richard

Wagner; he also stood up for the obscure theater of Luigi Pirandello

well before it was fashionable to do so. All in all, Procida seems to

have been a reasonable critic. Unfortunately, he is primarily thought

of today as the one who drove Enrico Caruso away from Naples. He reviewed

Caruso's debut at San Carlo in the tenor role of Nemorino in Donizetti's

L'elisir d'amore, performed on the evening of 30th December 1901. I've

been reading a bit about Saverio Procida. He was a well-known Neapolitan

journalist and critic who passed away in 1940 after a 50-year career

dedicated primarily to literature and music. He was in the forefront

of those who welcomed to Italy the new and difficult music of Richard

Wagner; he also stood up for the obscure theater of Luigi Pirandello

well before it was fashionable to do so. All in all, Procida seems to

have been a reasonable critic. Unfortunately, he is primarily thought

of today as the one who drove Enrico Caruso away from Naples. He reviewed

Caruso's debut at San Carlo in the tenor role of Nemorino in Donizetti's

L'elisir d'amore, performed on the evening of 30th December 1901.

I decided

to read the actual review and found it duly tucked away in the December

31, 1901, edition of il Pungolo (The Goad, an appropriately

provocative name for a newspaper). I had read that the review was "scathing".

Well, it isn't very kind --true-- and may, in fact, have been enough

to "goad" Caruso -- a temperamental fellow, anyway, by all accounts--

into leaving his native city.

Caruso

was not totally unknown in Naples before his debut at San Carlo, as

some think. The critic welcomes Caruso back to the city where he performed

at the Mercadante theater 5 years earlier. The review also acknowledges

Caruso's growing reputation and his recent success at La Scala in Milano

in the same role in L'elisir d'amore. The critic then starts

with some deft left-handed compliments (warming up for the strong rights

to come). Caruso has a "fine, baritone voice..." Caruso was a tenor,

so this, in itself, is a sharp left jab. (On the other hand, it is the

normal reaction of anyone who has ever heard a recording of Caruso.

He was, in fact, a natural baritone who developed a tenor register.)

The singer's voice has "good volume... it is even and broad... energetic...

displays rare power.. with a silver-like quality." So far --to continue

chasing a metaphor clearly much faster than I am-- if the critic were

a boxer, he is still sticking and moving ... sticking and moving.

Then, however:

| ...but

even given the natural quality of a gifted voice, it doesn't seem

to me that he has the technical skills that might add some discipline

to his natural gift, might put some more substance in his voice,

improve his sense of how melody should move, add the agility one

needs for light music such as that of Donizetti, straighten out

his uncertain intonation (perhaps --I hope-- this was just opening-night

nervousness). In short, I do not yet discern Caruso as living

up to the reputation provided him by his remarkably gifted natural

ability... |

The

next paragraph is a recipe, the critic's overbearing --even obnoxious--

prescription for Caruso: what music Caruso should sing and what music

he should avoid until his voice can handle it. In the latter category

are difficult roles, such as Tosca and all modern music.

After all, says the critic, bringing down the house (as Carusuo did)

with "Una furtiva lacrima" in L'elisir d'amore is not

really that difficult. An encore of that aria is a given, anyway. In

short, an untamed voice with potential. The critic hopes that "Caruso

will not be offended by my affectionate frankness". Ho-ho. Caruso was.

Caruso left after the seventh performance. (For more on Caruso,

see here.) The

next paragraph is a recipe, the critic's overbearing --even obnoxious--

prescription for Caruso: what music Caruso should sing and what music

he should avoid until his voice can handle it. In the latter category

are difficult roles, such as Tosca and all modern music.

After all, says the critic, bringing down the house (as Carusuo did)

with "Una furtiva lacrima" in L'elisir d'amore is not

really that difficult. An encore of that aria is a given, anyway. In

short, an untamed voice with potential. The critic hopes that "Caruso

will not be offended by my affectionate frankness". Ho-ho. Caruso was.

Caruso left after the seventh performance. (For more on Caruso,

see here.)

As a small

point of order, as I noted, Caruso was not entirely unknown in Naples

before that. I have in my possession an invitation to the wedding of

Di Marzo and Capozzi, the latter being my mother-in-law's aunt (kinship

anthropologists among you are free to invent your own name for that

-- grand-aunt-in-law?). The wedding was on August 26, 1896. There was

music of Wagner, Bizet, Gounod, and Faure. There was a 6-piece orchestra,

two of whom were singers. The tenor was 21-year-old Enrico Caruso. Ominously,

the program also tells us that the harmonium player and conductor was

Vincenzo Lombardi. The band-leader was Vince Lombardi! (And they thought

Toscanini was tough.)

--(at halftime)--

"Congratulations,

laay-deeez! You've just turned a wedding into a funeral! Johnson,

a 12-measure rest doesn't mean you get to sleep for the rest of the

piece, understand? Hey, Caruso, is that supposed to be vibrato?

If these people wanted to hear someone yodel, they'd get married in

Switzerland! And did you get another sandwich stuck in that golden

gorge of yours? You lay off the snacks. Them's for the guests, and you're

a singer -- or at least that's what the sign says. My grandmother croaked

17 years ago and she still has a better high B-flat than that. So, if

I may now remind you girls that those funny little marks in front of

some of the notes are called 'sharps' and 'flats', maybe we can go back

out there and not totally embarrass ourselves. Now get back out there

and play! --Caruso! Put down the cannoli!"

Metropolitana

(1)

It's

fun to watch them work on the new metropolitana subway station at Piazza

della Borsa in downtown Naples. Actually, you watch a lot of men in

hard-hats stand around leaning on their shovels waiting for a lonely

archaeologist to finish sorting these bits into one box and those pieces

into another box. The station is at sea-level and right on top

of part of the ancient Roman southern wall of the city. That wall apparently

incorporates even older segments of the original Greek wall of Neapolis;

thus, it is a treasure trove for archaeologists -- but a stumbling block

for those whose main concern is a huge urban population without adequate

rapid transit. Some of the unearthed segments of the wall, however,

have now been reinforced and cemented in place; thus, maybe the rumor

is true: they are planning to make it all a sort of combination museum/train

station. It's

fun to watch them work on the new metropolitana subway station at Piazza

della Borsa in downtown Naples. Actually, you watch a lot of men in

hard-hats stand around leaning on their shovels waiting for a lonely

archaeologist to finish sorting these bits into one box and those pieces

into another box. The station is at sea-level and right on top

of part of the ancient Roman southern wall of the city. That wall apparently

incorporates even older segments of the original Greek wall of Neapolis;

thus, it is a treasure trove for archaeologists -- but a stumbling block

for those whose main concern is a huge urban population without adequate

rapid transit. Some of the unearthed segments of the wall, however,

have now been reinforced and cemented in place; thus, maybe the rumor

is true: they are planning to make it all a sort of combination museum/train

station.

That is

happening at a number of the new subway stations. The one adjacent to

the archaeological museum has --encased in plexiglass over the entrance!--

the original, splendid bronze horse's head

presented by Lorenzo the Magnificent (1449-92) to Diomede Carafa, the

representative of the Aragonese court in Naples in the late 15th century.

It had been on display in the museum, itself; now it's in a subway station.

This approach to "art for the masses" has left some people delighted,

and others less so.

Counterfeits

One

of the most interesting collections in the National Museum is Naples

is the one dedicated to counterfeit coins from the 18th century. At

the time, the archaeological digs had recently opened at Pompeii and

Herculaneum, both buried by the massive eruption of Vesuvius almost

two millennia earlier. With interest in Roman artifacts running high

at the Bourbon court of Naples, enterprising locals started turning

out "genuine" Roman coins. After more than two centuries, these coins

have, themselves, now acquired a decent numismatic value. One

of the most interesting collections in the National Museum is Naples

is the one dedicated to counterfeit coins from the 18th century. At

the time, the archaeological digs had recently opened at Pompeii and

Herculaneum, both buried by the massive eruption of Vesuvius almost

two millennia earlier. With interest in Roman artifacts running high

at the Bourbon court of Naples, enterprising locals started turning

out "genuine" Roman coins. After more than two centuries, these coins

have, themselves, now acquired a decent numismatic value.

Naples

has always had a reputation as a hub of counterfeit goods. It is no

problem at all to walk into some stores in town and buy brand name clothes,

handbags and shoes that look like the real thing and that may even be

well made. Whether or not what you buy really is the real thing,

however, depends on the luck of the draw. The counterfeits should cost

less.

Currently

there is an epidemic of counterfeit watches. In the past, if I was approached

on the street and offered a "genuine Rolex," and I looked at the watch

and saw "R-O-L-L-E-K-S," then even I had enough street savvy to demur

politely. ("I already own a K-A-R-T-I-E-R.") The problem with the new

counterfeits is that they are so good that even an expert from Rolex

or Cartier has to take a second (and third) glance at them. The watches

have turned up in reputable stores where at least one prominent merchant

claims he bought them legitimately from a company in Milan that had

imported them. Everyone concerned claims to have paid the appropriate

import duties and other taxes.

I didn't

notice it at first, but a few days after I bought a new pair of eye-glasses,

I had occasion to examine the frames more closely. "Giorgio Armani"

is inscribed on them. I flattered myself into thinking that I was wearing

a fashionable set of specs. I know he makes clothing -- but frames for

glasses? I don't know.

names

My

wife's friend goes to a cardiologist here whose name is Adolfo Tedesco.

That surname is not uncommon in this part of Italy. It means "German".

Geographic surnames -- indicating family origin back in the middle ages--

are common in Italy. The most striking one I know of in Naples is "Ostrogoto"

--Ostrogoth-- a name presumably traceable to the Germanic invasions

of Italy at the fall of the Roman Empire. My

wife's friend goes to a cardiologist here whose name is Adolfo Tedesco.

That surname is not uncommon in this part of Italy. It means "German".

Geographic surnames -- indicating family origin back in the middle ages--

are common in Italy. The most striking one I know of in Naples is "Ostrogoto"

--Ostrogoth-- a name presumably traceable to the Germanic invasions

of Italy at the fall of the Roman Empire.

Back to

Adolfo Tedesco. Adolf German. This was a very good name to have in Italy

between 1933 and 1943. You can be certain that the doctor was born during

those years. No doubt, he has had to put up with good-- or maybe not

so good-natured ribbing since then, however.

A cursory

stroll through the Naples telephone book reveals surnames from the slightly

unorthodox Fava (Lima bean),

Bavoso (slobbering) and Mezzatesta

(half head) to sublime if unoriginal combinations of first and

surname, such as Pasquale Pasquale

(Easter Easter) and Domenico di Domenico

(Sunday of Sunday). In between are surnames such as Moccio (Snot), Malavita (Organized Crime), Quattrocchi (Four Eyes), Violino (Violin), Mangiaterra (Earth-eater) and Malato

(Sick). For no particular reason, I like the first/last name

combinations of Armando Uomo

(Man), Antonio Sesso (Sex),

Fortunato Capodanno (Fortunate

New Year) Sergio del Bufalo,

Baldasare Della Confusione,

Bianca Barba (White Beard),

Felice Popolo (Happy People),

Nello Albero (In The Tree)

and one that must be challenging to live up to — Salvatore

Delle Donne (Saviour of Women). Also, the building next to mine

was built by an engineer with the unusual though not unique surname

Della Morte (Of Death). Then his parents christened him Angelo. His name was Angel of Death. ("Uh,

dear, what's your young gentleman's name? That's nice. Well, run along,

but be back before the moon rises, won't you?")

The absolute

worst, the utmost in baneful and pernicious handles to have attached

to your person if you are Italian is the surname "Bocchino". Besides

being the proper word for 'cigarette holder' or 'mouthpiece of

a musical instrument', it is the vulgar slang term for 'fellatio'. There

are seventeen of them in the Naples phone book, and an entire segment

of a recent TV program was dedicated to the problems of a gentleman

with that surname whose parents had seen fit to give him the first name

of "Generoso". There are also a number of entries in the local

phone book for "Zoccola". It means, precisely, 'slut', and a newspaper

article on this subject speculated that even if a man were perfect in

all else, he might have difficulty getting a woman to marry him, because

no woman wants to be introduced in society as "Mrs. Slut".

A victim

of a slightly different sort is Paolo Porcellini, whose surname means

'little pigs' and who has two brothers. It so happens that

the Italian version of the famous Disney jingle 'Who's Afraid of the

Big Bad Wolf' starts 'Siam tre piccoli porcellini…' ('We

are three little pigs'), rousing choruses of which, sung by mean-spirited

classmates, inevitably awaited the Piglet Brothers on many a school

day. Finally, other disconcerting Italian surnames are Piscione

and Cacace, which evoke

the acts of excretion; Schifone,

which means 'most disgusting'; Cazzato,

Cazzola, or Cazzoli, all of which recall the most

common slang term for 'penis'; and Finocchio,

the vegetable 'fennel, but also the common disparaging term for

'homosexual'.

Why not,

then, simply change your name? In Italy, there is an awesome battle

of documents to be fought. In large Italian cities, about 6 or 7 people

a year apply to modify their surname, 50 a year to change their surname

completely, and 100 a year their first name. Even after the change,

creating a new identity for yourself is so overwhelming, that most simply

forget about it. There are new driving licenses to get, insurance, bankbooks,

tax forms, a new phone listing—in short, every shred of official

paper with your name on it has to be amended. Worse, you have to

deal with the infamous Hall of Records 'Bureausaurus' (as they

are so aptly nicknamed in Italy), someone who explains to you patiently

that you can't get a document attesting to your new name unless you

first present a document attesting to your new name.

|