©

2004 Jeff Matthews & napoli.com

Aqueduct,

Roman—

For

those who are not claustrophobic—nay, for those who absolutely

revel in their claustrophilia—I recommend a visit to the Roman

aqueduct system that supplied Naples. It is one of the most impressive

feats of engineering undertaken in Naples during the reign of Caesar

Augustus. The aqueduct was 170 km long and started at a reservoir fed

by the river Serino. There were two branches: one led to Beneventum

and the other to Neapolis. The one to Naples approached the city

from the slopes of Capodimonte, then went on to Vomero and to Posillipo,

the hill bounding the western end of the city. From Posillipo, a secondary

branch lead through the hill and to Fuorigrotta and beyond, to Puteoli,

modern day Pozzuoli. Parts of the aqueduct were open and others

were tunnels through the rock. For

those who are not claustrophobic—nay, for those who absolutely

revel in their claustrophilia—I recommend a visit to the Roman

aqueduct system that supplied Naples. It is one of the most impressive

feats of engineering undertaken in Naples during the reign of Caesar

Augustus. The aqueduct was 170 km long and started at a reservoir fed

by the river Serino. There were two branches: one led to Beneventum

and the other to Neapolis. The one to Naples approached the city

from the slopes of Capodimonte, then went on to Vomero and to Posillipo,

the hill bounding the western end of the city. From Posillipo, a secondary

branch lead through the hill and to Fuorigrotta and beyond, to Puteoli,

modern day Pozzuoli. Parts of the aqueduct were open and others

were tunnels through the rock.

That Posillipo

aqueduct runs parallel to the Roman tunnel known as the Seiano

Grotto and was apparently built at the same time as the tunnel,

itself. The tunnel is occasionally open for visits. As far as I know,

the aqueduct is not; I know of its existence only because I was led

into it by a crazy archaeologist friend of mine. It was there that I

found out that I don't particularly like to be cooped up in tight spaces

beneath mountains.

In the

city of Naples, itself, the water distribution was by a system of subterranean

conduits leading from the main aqueduct. More recently, during the aerial

bombardment of WW II, the ancient aqueduct was put to use as an air-raid

shelter, the wells and cisterns being enlarged to allow for the passage

of people. There are underground tours available of the section of the

aqueduct directly below the historic center of the city. The aqueduct

is appropriately dark, deep, and scary. Visitors are even issued candles

to light their descent. It is also very, very cold, which makes it the

perfect place to visit in July and August. The entrance is from Piazza

Gaetano near the intersection of via dei Tribunali and via

San Gregorio Armeno. (At #33 on the map of the historic center of

the city. Click here.)

Bourbons

(6); Savoy (4)

Concerning

the visit of the Savoys to Naples, the city of Naples backtracked and

accepted a gift from Victor Emanuel and also turned to flapdoodle the

official line that the Savoys are "just private citizens like anyone

else and we aren't going to baby-sit them". Indeed, the mayor of Naples,

Mrs. Iervolino, and the ex-mayor (now president of the Campania region),

Mr. Bassolino, both showed up to say hello. Concerning

the visit of the Savoys to Naples, the city of Naples backtracked and

accepted a gift from Victor Emanuel and also turned to flapdoodle the

official line that the Savoys are "just private citizens like anyone

else and we aren't going to baby-sit them". Indeed, the mayor of Naples,

Mrs. Iervolino, and the ex-mayor (now president of the Campania region),

Mr. Bassolino, both showed up to say hello.

The ex-Royal

family (photo) of Italy got to sit in the ex-royal box (now the presidential

box) at San Carlo; Victor Emanuel got to visit the building he was born

in (the Royal Palace); and they all went to the Brandi restaurant (which

made the first "Margherita" pizza for Victor's great-grandmother). Young

"prince" Filiberto took in a soccer match at San Paolo and watched home

team Naples struggle to a scoreless tie, thus continuing a nosedive

out of the B League—already a "minor" league—into the very

minor C League.

There were

a few demonstrations, both pro and con. The pros were old-line monarchists

who didn't vote for the Republic in the referendum of 1946. They have

a few modern sympathizers, although it is fair to say that most modern

Italians accept their republic (whatever it faults) as a way of life

and view the Italian monarchy as a relic—which it is.

A recent

copy of the Neo-Bourbon newspaper, Journal of the Two Sicilies.

The

most curious demonstrators were the "antis". Some of them were simply

republicans and against monarchies. Their point was to demonstrate against

any sort of official kow-towing to a Man Who Would Be King—although

that is not going to happen and everyone knows it. What caught the eye

was the strange cult of "neo-Bourbons" that showed up with signs that

read "Assassins!" and "Hyenas!" The

most curious demonstrators were the "antis". Some of them were simply

republicans and against monarchies. Their point was to demonstrate against

any sort of official kow-towing to a Man Who Would Be King—although

that is not going to happen and everyone knows it. What caught the eye

was the strange cult of "neo-Bourbons" that showed up with signs that

read "Assassins!" and "Hyenas!"

It is an

oft-repeated assertion in the south of Italy that all of the problems

of the south started with the union of Italy in 1860 under the Savoy

dynasty. That is when the problem of "Two Italys" started, when unemployment

started, and when massive emigration started to deplete the greatest

resource any nation has—its people.

While it

is true that the north bungled the unity of Italy by failing to deal

with the problems of the south, they didn't invent those problems. To

a large extent they inherited them. The entire course of the 19th century

in Italy is bound up in the risorgimento, the movement to create

a united, modern nation state of Italy out of the geopolitical jigsaw

puzzle that had existed on the peninsula for over a thousand years.

That drive to unity was not a northern invention, either. Many of the

"philosophers of unity" such as the historian, Vincenzo Cuoco, were

from Naples. The Kingdom of Naples was also the home of the "carbonari" in the 1820s, the first agitators

for unity, whose ideals fed into the risorgimento later in the

century.

That movement

towards a united Italy was totally resisted by the Bourbons.

For three decades leading up to Garibaldi's

invasion of the south in 1860 to force union on the Kingdom of Naples,

the Bourbon dynasty of Naples was a despotic, absolute monarchy. It

resisted even granting a basic constitution and parliament to the people,

and it had to rely on Austrian and Swiss mercenaries to prop up the

kingdom because the king no longer even trusted his own officer corps,

many of whom were agitating for a united Italy as a sort of "manifest

destiny". The Bourbon kings remained oblivious to the political reform

movements that were sweeping all of Europe in the middle of the 19th

century. They had their century—the 18th—and they liked

it just fine, thank you very much.

Economically,

the north also inherited a largely agricultural society with a system

of land management based on large holdings worked by a permanently poor

class of farmers, a system that had not changed much since the feudalism

of the Middle Ages. This, after much of northern Italy and Europe had

gone over to metayage—tenant farming, where the people

who worked the land kept a considerable portion of what they produced.

The "neo–Bourbons"

fail to mention that as Garibaldi marched north from Sicily towards

Naples in the summer of 1860, he was seen largely as a liberator by

the long-suffering peasantry. He then spent almost a year as "Dictator

of Naples" making Karl Marx seem like a cautious reformer. Garibaldi

expropriated land barons and gave the land to farmers. He set up free

schools as a cure for illiteracy, which was endemic in the south. If

the Savoys are guilty of a historical crime, it is that they undid those

reforms the minute they put Garibaldi out to pasture.

But bring

back the Bourbons? They must be kidding.

Cars (2)

I

'm not sure what kind of foreign car is the most popular in Naples.

You see a lot of the official car of Lilliput nowadays, the Smart,

a two–seater (photo). It is made by Mercedes and Swatch (from

Swiss Watch, the gnomes who make those screwy–looking transparent

wristwatches where you can actually see the springs and cogs of the

works. The Smart is not cheap, in spite of its diminutive size, but

it is easy to park, which I suppose is an advantage. I did know one

of the nouveaux riches in Naples who had the ostentatiously bad

taste to get himself a Rolls Royce. I have no idea if he ever took it

out of the garage. I have no idea even where the garage was; it was

probably some sort of a secret cavern where he could enwomb himself

in his expensive toy in solitude, fondle the steering wheel and feel

completed in life. There are a few Mercedes around—the real ones:

somber, well designed, solidly built, wall-to-wall airbags and even—as

an optional—a cigar-smoking industrialist in the back seat. There

are some Volvos and Saabs, too. Having a new high–tech German

or Swedish set of wheels around here, though, is asking for trouble.

There is a big market for them, and they say that if you park one in

the wrong part of town, some sheikh will be driving your car around

downtown Riyadh a few days from now. I

'm not sure what kind of foreign car is the most popular in Naples.

You see a lot of the official car of Lilliput nowadays, the Smart,

a two–seater (photo). It is made by Mercedes and Swatch (from

Swiss Watch, the gnomes who make those screwy–looking transparent

wristwatches where you can actually see the springs and cogs of the

works. The Smart is not cheap, in spite of its diminutive size, but

it is easy to park, which I suppose is an advantage. I did know one

of the nouveaux riches in Naples who had the ostentatiously bad

taste to get himself a Rolls Royce. I have no idea if he ever took it

out of the garage. I have no idea even where the garage was; it was

probably some sort of a secret cavern where he could enwomb himself

in his expensive toy in solitude, fondle the steering wheel and feel

completed in life. There are a few Mercedes around—the real ones:

somber, well designed, solidly built, wall-to-wall airbags and even—as

an optional—a cigar-smoking industrialist in the back seat. There

are some Volvos and Saabs, too. Having a new high–tech German

or Swedish set of wheels around here, though, is asking for trouble.

There is a big market for them, and they say that if you park one in

the wrong part of town, some sheikh will be driving your car around

downtown Riyadh a few days from now.

I may have

been the only person in Naples with an American Motors Corp. Concord,

a fine machine from 1979. It used to draw stares, "oohs" and "aahs"

when I brought it up out of my own Bat Cave for my nightly patrols through

the by-ways of Naples. It wasn't what Europeans disparagingly term an

"American battleship". They are remembering way back when—the

1950s—when American drivers were shameless love–slaves of

the Godzillamobile, a gaudy behemoth with tail-fins aerodynamically

honed to create intense low pressure vortices in their wake, vacuuming

up little old ladies from curbside and blowing them down the streets

like geriatric Dorothys on their way to Oz. One turn signal, alone,

pulled more juice than it took to reanimate Boris Karloff in The Return

of Frankenstein, and in fossil–fuel consumption, those cars barely

got two miles to the dinosaur. My Concord wan't any of that—it

just wasn't a "European-looking" car.

Still way

back when, my parents indeed bought a European-looking car. It looked

that way because it was a European car—a small Citroen 2CV. We

made a trip from Los Angeles to New York and back. The 2CV made it,

suffering no more than an occasional hayseed jibe about us having to

scrounge spare parts from boxes of Cracker Jacks. It was a good car,

not fragile—in spite of the salesman's warning not to kick the

tires.

It made

that trip fine, just the way I made it fine in my last big trip in the

Concord--way up to Switzerland, even motoring up over the Alps instead

of through the long, dreadful Gotthard tunnel. On the way back down

south, I strayed from the autostrada near Naples onto a road that even

the world's greatest optimist might call "What Road?!"—

a trail ludicrously overrated on my map as a vague tracing of broken

squiggles. I wound up in a village where children fled from my path

and wide-eyed peasants threw sprigs of wolfbane at my car. (Or maybe

it's "cloves" of wolfbane, or some metric unit like "kilobushes".)

I pulled

up in front of City Hut to ask directions, and a village elder appeared.

He eyed my car suspiciously since it had just been seen to move without

benefit of harnessed brute. Helpfully, he set the townsfolk to sharpening

stakes and gathering firewood until I explained with my map that it

had been all downhill from Switzerland. He was impressed, too, that

Switzerland was a mere eleven inches from his village. He seemed fully

conversant with the technology of the wheel since he tried to converse

with my tires. When they wouldn't answer, he stared kicking them, shaking

his head and "tsk–tsking" as he went. I turned down his offer

of a trade–in for a fine, slightly used mule. He even kicked the

poor animal in the shins a few times just to show me what a good, solid

beast it was. In any event, they let me go and I drove off back to Naples,

but only after letting every adult in the village sit in the front seat

of my Concord, fondle the steering wheel and feel completed in life.

| I

am beginning to see that agriculture will not be perfect in a people

until those who farm the land are the same ones who own the land. |

When

I read that, I immediately think of revolutionaries and reformers from

the middle of the 19th century. Yet, the words were written a bit earlier

than that, and they come from a source that, perhaps, many non–Italians

have not heard of: Vincenzo Cuoco, a Neapolitan historian who lived

from 1770 to 1823. When

I read that, I immediately think of revolutionaries and reformers from

the middle of the 19th century. Yet, the words were written a bit earlier

than that, and they come from a source that, perhaps, many non–Italians

have not heard of: Vincenzo Cuoco, a Neapolitan historian who lived

from 1770 to 1823.

Cuoco was

caught up in the spirit and times of late 18th–century Europe:

Enlightenment and Revolution. He was part of the Neapolitan Enlightenment

and part of the revolution that gave birth to the Neapolitan Republic

of 1799. The Bourbons overthrew the Republic after a few short months

and punished Cuoco by confiscating his property and sentencing him to

20 years of exile. Then, when the French took over the Kingdom of Naples

in 1806, he returned home and took an active part in the 10-year French

rule in Naples. At the second return of the Bourbons in 1815, he was

permitted to stay in Naples, where he died in 1823, clouded by mental

illness. At least, the Bourbons had spared Cuoco's life in 1799, and

he lived to write the works he is remembered for.

The best

known one is Saggio Storico sulla Rivoluzione Napoletana nel 1799

(History of the Neapolitan Revolution of 1799). He published it anonymously

in 1801 and under his own name in 1806; it is the seminal work for those

interested in that episode of history and, though his view is not the

only one on why the revolution failed, Cuoco is the first to deal with

that question:

Since

our revolution was a passive one, the only way for it to be successful

would have been to gain the opinion of the people. But the view

of the patriots was not the same as that of the people; they had

different ideas, different customs, and even two different languages.

The very same admiration for things foreign, which held back our

culture as a kingdom, formed the basis for our republic and was

the greatest obstacle to the establishment of liberty. The Neapolitan

nation was split in two, separated over two centuries into two

very different kinds of people. The educated classes were formed

on foreign models and possessed a culture quite different from

one that the nation needed, one that could come about only through

the development of our own faculties. Some had become French,

and some English; and those that stayed Neapolitan—most

of the people—stayed uneducated.

[From Saggio Storico sulla Rivoluzione Napoletana nel 1799.

The translation is mine.] |

A lesser–known

work—and the one the quote at the beginning of this log entry

is taken from—is Platone in Italia (Plato in Italy), a

bit of historical fiction in which Cuoco claims to be merely translating

a manuscript written by Plato, himself. Of course, no one believed that,

and Cuoco knew that no one believed that, but it gave him a vehicle

for his ideas on just what was wrong with society and how it could be

remedied.

Platone

in Italia is a series of dialogues between Plato and his disciples

set in Italy during Plato's lifetime—that is, approximately 400

b.c. Cuoco—speaking as Plato—reveals his fascination with

the ancient pre-Roman peoples of Italy, especially the Etruscans and

the Samnites, two cultures older than Greece and which—much more

so than Greece—should serve as a model for modern Italy. Italy

really had nothing to thank the Greeks for, since the Italic cultures

were older than that of Classical Greece. Modern Italians (meaning in

the early 19th century, when Cuoco was writing) had nothing to fear

from the ideas of confederation (like the Etruscans) or a non-feudal

system of land management—small farms owned and worked by the

citizenry (like the Samnites). After all, none of this, says Plato/Cuoco,

is new and revolutionary; it goes way back to our own Italic roots.

The book

is actually amusing in that it has Plato sounding off on various occasions

about how backwards "we Greeks" really are compared to the older and

wiser peoples of Italy. Cuoco, of course, is throwing this in the face

of the cliché that Italy (meaning the Romans) became educated

only after they had conquered Greece and absorbed some wisdom. Platone

in Italia did very well for a number of years—perhaps in the

afterglow of the French Revolution—but it then drifted into obscurity.

I was reminded of all this when I passed the Vincenzo Cuoco Liceo the

other day. He might be happy to know that two centuries later, there

is a high school in Naples named for him.

"Little

King," the ("Reuccio")

Affectionately

called the Il Reuccio"—the "little king" —by

Neapolitans, Charles II (1661-1700), King of Spain, was the last

ruler of the once mighty Spanish empire and, thus, is the last

in the line of Spanish monarchs to rule Naples. He died without an heir

and designated as his successor Phillip of Bourbon , Duke of Anjou,

and nephew of the king of France. This effectively turned France and

Spain into allies, a union potentially so strong that England, Holland,

and the Holy Roman Empire of Leopold I formed a Grand Alliance to fight

it. This set off the Wars of the Spanish Succession, which raged

across Europe until 1713. The statue in the photo is at Piazza Monteoliveto,

one block up from the main post office on Via Monteoliveto. Affectionately

called the Il Reuccio"—the "little king" —by

Neapolitans, Charles II (1661-1700), King of Spain, was the last

ruler of the once mighty Spanish empire and, thus, is the last

in the line of Spanish monarchs to rule Naples. He died without an heir

and designated as his successor Phillip of Bourbon , Duke of Anjou,

and nephew of the king of France. This effectively turned France and

Spain into allies, a union potentially so strong that England, Holland,

and the Holy Roman Empire of Leopold I formed a Grand Alliance to fight

it. This set off the Wars of the Spanish Succession, which raged

across Europe until 1713. The statue in the photo is at Piazza Monteoliveto,

one block up from the main post office on Via Monteoliveto.

The building seen

behind the statue in the photo is of extreme interest. It is part of

what was once one of the largest monasteries in Italy and is, perhaps,

the least written about of all such religious structures in Naples.

Construction started in 1411 and over the centuries devopled into a

mini-city inhabited by members of the Monteolivetan order. The complex

was largely broken up in the wake of the suppression of monasteries

in Napoleonic Europe in the early 1800s and has undergone

subsequent subdivision. The part in view behind the statue in

the photo is currently a large barracks for the Carabinieri, the uniformed

Italian national police force. (The dark building attached to the left

of the barracks is the Church of Monteoliveto --still a church.) The

entire complex stretched further downhill to the south for 150 yards

to the main cloister of the monastery. That part of the complex is closed

but was left intact and actually incorporated into the main Naples post

office when that building was put up in the 1930s (photo at right).

In effect, the entire modern city block surrounds the old monastery. The building seen

behind the statue in the photo is of extreme interest. It is part of

what was once one of the largest monasteries in Italy and is, perhaps,

the least written about of all such religious structures in Naples.

Construction started in 1411 and over the centuries devopled into a

mini-city inhabited by members of the Monteolivetan order. The complex

was largely broken up in the wake of the suppression of monasteries

in Napoleonic Europe in the early 1800s and has undergone

subsequent subdivision. The part in view behind the statue in

the photo is currently a large barracks for the Carabinieri, the uniformed

Italian national police force. (The dark building attached to the left

of the barracks is the Church of Monteoliveto --still a church.) The

entire complex stretched further downhill to the south for 150 yards

to the main cloister of the monastery. That part of the complex is closed

but was left intact and actually incorporated into the main Naples post

office when that building was put up in the 1930s (photo at right).

In effect, the entire modern city block surrounds the old monastery.

[Also

see here for an item on the modern use

of old monasteries.

Parthenope,

Ulysses

| When

we had got within earshot of the land, and the ship was going

at a good rate, the Sirens saw that we were getting in shore and

began with their singing.'Come here,' they sang, 'renowned Ulysses,

honour to the Achaean name, and listen to our two voices. No one

ever sailed past us without staying to hear the enchanting sweetness

of our song—and he who listens will go on his way not only

charmed, but wiser, for we know all the ills that the gods laid

upon the Argives and Trojans before Troy, and can tell you everything

that is going to happen over the whole world.'

They

sang these words most musically, and as I longed to hear them

further I made by frowning to my men that they should set me

free; but they quickened their stroke, and Eurylochus and Perimedes

bound me with still stronger bonds till we had got out of hearing

of the Sirens' voices. Then my men took the wax from their ears

and unbound me.

—The

Odyssey (trans. Samuel Butler)

|

Like

most of my generation, I got my classical education from the venerable

Classic Comics. I grew up thinking that most of that ancient Greek stuff

happened—well, over in Greece somewhere. Little did I know that

the episode of the Sirens took place in these waters. There are tiny

rocks sticking up out of the water on the Amalfi side of the Sorrentine

peninsla named for those very Sirens that tempted Ulysses. One of the

Sirens, Parthenope, threw herself into the sea out of despair over what

she believed to be her lack of allure, and her body washed up on the

coast a few miles away at the spot where mythology says the city

of Neapolis (Naples) was founded. Actually, that would be the city of

Parthenope, which then became Neapolis; indeed, modern Neaplotans still

refer to themselves commonly as "Parthenopeans". Like

most of my generation, I got my classical education from the venerable

Classic Comics. I grew up thinking that most of that ancient Greek stuff

happened—well, over in Greece somewhere. Little did I know that

the episode of the Sirens took place in these waters. There are tiny

rocks sticking up out of the water on the Amalfi side of the Sorrentine

peninsla named for those very Sirens that tempted Ulysses. One of the

Sirens, Parthenope, threw herself into the sea out of despair over what

she believed to be her lack of allure, and her body washed up on the

coast a few miles away at the spot where mythology says the city

of Neapolis (Naples) was founded. Actually, that would be the city of

Parthenope, which then became Neapolis; indeed, modern Neaplotans still

refer to themselves commonly as "Parthenopeans".

I have

found what I understand is the only piece of ancient sculpture in Naples

depicting the siren, Parthenope. It is a small bust, and is located

on the premises of the Municipio, the City Hall. It was recovered from

the site of the original Greek acropolis of the city of Neapolis, on

the height across from today's Piazza Cavour. That location is not currently

an active archaeological site, and it has been covered with centuries

of construction, most recently various departments of the University

of Naples Medical School. On the historic map of the city (click here) you would start at #37 and walk up the hill

(towards the top of the map).

Maintenance

and upkeep, Mostra d'Oltremare, Piazzale Tecchio

My

theological qualifications are ridiculously peccable, so when I say

I couldn't find a Patron Saint for those who perform Maintenance and

Upkeep, I may, indeed, have missed him or her. There is Expeditus (also

known as Elpidus), the saint against procrastination and for expeditious

or prompt solutions. Also, Saint Barbara and Saint Thomas the Apostle

(better remembered as "doubting") are both listed as saints for construction

workers. All of these are close to what I am looking for…but… My

theological qualifications are ridiculously peccable, so when I say

I couldn't find a Patron Saint for those who perform Maintenance and

Upkeep, I may, indeed, have missed him or her. There is Expeditus (also

known as Elpidus), the saint against procrastination and for expeditious

or prompt solutions. Also, Saint Barbara and Saint Thomas the Apostle

(better remembered as "doubting") are both listed as saints for construction

workers. All of these are close to what I am looking for…but…

One of

the most maddening things about Naples is that they build beautiful

things and then let them fall apart. Some years ago, they city decided

to redo the square in front of the San Paolo soccer stadium, Piazzale

Tecchio. They turned it from a squalid clot of traffic and noise into

a vast pedestrian zone, replete with banks of brick bleacher-type seats

for students from the adjacent university buildings and a large area

surfaced with natural, rough-hewn wooden planks. All that plus the new

trees gave the students and passers–by a pleasant place to sit

outside in a busy city and enjoy their lunch and maybe a fine day.

I passed

by that spot yesterday and the wooden surface is rotted and warped,

and there are weeds growing up between the cracks (photo). Years of

weathering and no maintenance will do that. As a result, the entire

area is closed and cordoned off by that orange plastic web fencing that

they string around construction sites to keep lollygaggers away. That,

too, has been pushed down and trampled underfoot in places by pedestrians

trying get across the square along the narrow walkway that has been

left open. Bare, rusted spikes that held the fence in place stick up

along the route. It's a pit.

The stadium

is adjacent, also, to the east end of the mammoth Mostra d'Oltremare—the

Overseas Fair Grounds—an area about one mile long by several hundred

yards wide. It was opened in the late 1930s and was part of the Fascist-era

splurge of construction in Naples. It had thousands of Mediterranean

pine trees, a zoo, buildings for expositions, and—the crown jewel—the

arena flegrea, an outdoor theater, the backdrop of which was

a colourful mosaic. The wings led from both sides to access paths around

to the production area where props were stored. Through the 1950s, summer

productions of Aida were an annual event. The most spectacular

feature at the Mostra was a suspension cable-car that led from the fair

grounds up and over the trees to a point on the Posillipo ridge hundreds

of yards distant and 300 feet above sea-level to overlook the entire

bay of Pozzuoli to the west.

The zoo

is still there, as are many of the trees, but the fountain has not fountained

in years, nor has the theater been used in decades. Many of the buildings

have fallen to ruin, and if you wander into the still ample wooded sections,

you can see what is left of buildings jutting out or toppled over. In

many cases, newer and very ugly buildings have been put up over the

years in that formless quick–and–dirty prefabricated slab

style of the 50s and 60s. The grounds are still used to host yearly

events such as book and computer fairs, and some university buildings

are also on the premises. The cable lift to Posillipo has, of course,

not run since the 1950s.

There are

two possibilities, both of which have to do with my search for the right

saint: one, either the saint does not exist and, thus, those people

charged with keeping things looking spiffy and fine have no need to

curry favor with the gods; or, two, the saint does exist and those same

people figure they don't have to worry about it because the saint has

it covered. This is a Thomistic dilemma, indeed, and I tremble before

it.

Seiano

Grotte (1)

As early as the Republic of Rome and then during the first centuries

of Empire, the coastal area of the Bay of Naples was the site of a number

of aristocratic residences. One of the best-loved places to put your

aristocratic villa in those days was on the seaside slope of the great

hill of Posillipo at the western end of the bay. The name Posillipo

—Greek for "the place where unhappiness ends" expresses the

sense of serenity which Imperial Romans must have derived from this

lovely promontory. Recent excavations along the seaside in the area

of the small island of Gaiola and the nearby coastal area of Marechiaro

have uncovered numerous traces of Roman habitation, including the ruins

of a theatre built to accommodate some 2,000 spectators, and an odeion,

a theater for musical performances. As early as the Republic of Rome and then during the first centuries

of Empire, the coastal area of the Bay of Naples was the site of a number

of aristocratic residences. One of the best-loved places to put your

aristocratic villa in those days was on the seaside slope of the great

hill of Posillipo at the western end of the bay. The name Posillipo

—Greek for "the place where unhappiness ends" expresses the

sense of serenity which Imperial Romans must have derived from this

lovely promontory. Recent excavations along the seaside in the area

of the small island of Gaiola and the nearby coastal area of Marechiaro

have uncovered numerous traces of Roman habitation, including the ruins

of a theatre built to accommodate some 2,000 spectators, and an odeion,

a theater for musical performances.

A most

singular bit of construction, however, is the spectacular Seiano Grotte,

an 800-meter tunnel through the Posillipo hill itself, from the western

area of modern Bagnoli through to the sea. It was apparently a private

tunnel and allowed easy access to the spectacular clifftop estate of

Vedius Pollio. The tunnel was probably

built by Lucius Cocceus Auctus, the same engineer responsible for the

Gallery of Peace, a tunnel and important part of the fortifications

of the Roman Imperial Port in Baia.) Auctus also built the

major tunnel that the Romans used to get to Naples from the West. (Today,

that tunnel parallels and is between the two modern

traffic tunnels that go from Mergellina through the hill to Fuorigrotta.

It was in common use until the completion of the two recent tunnels,

one in the 1880s and the other in the 1920s.) The Seiano Grotto is high

and spacious; it was ventilated by three air ducts opening on the sea.

It fell into disuse over the centuries, but was later reopened by the

Bourbons in 1841. Bourbon restoration was extensive and provides

interesting comparison to the original Roman masonry evident in many

places. The Bagnoli entrance (shown in the photo) has recently been

restored and, on occasion, the tunnel and grounds of the Vedius Pollio

estate may be visited.

(Also,

see this entry on Posillipo.)

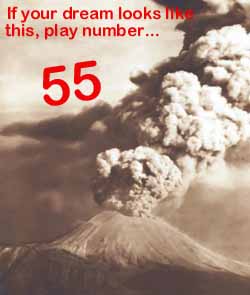

Smorfia

(2), dreams (2)

Looking

at the entry for the smorfia, I am still not quite sure what numbers to

play in the lottery this week. I had an ominous dream the other night

and when I try to get some help from the neigborhood stable of oneirocritics

in my morning coffee-bar as to what numbers my dream adds up to—that

is, what symbols (such as "Vesuvius") correspond to what numbers in

the Neapolitan bible for such things, la smorfia—they

get nervous and touch certain parts of the body, which action is said

to ward off bad luck, the evil eye, and all the rest. Looking

at the entry for the smorfia, I am still not quite sure what numbers to

play in the lottery this week. I had an ominous dream the other night

and when I try to get some help from the neigborhood stable of oneirocritics

in my morning coffee-bar as to what numbers my dream adds up to—that

is, what symbols (such as "Vesuvius") correspond to what numbers in

the Neapolitan bible for such things, la smorfia—they

get nervous and touch certain parts of the body, which action is said

to ward off bad luck, the evil eye, and all the rest.

I dreamt

that Vesuvius erupted. Now, I have had the normal run-of-the-mill dreams

of interest to headshrinkers, I suppose, but I have never had any prophetic

dreams. I have read about them, of course, and put them in that part

of my brain-closet where I keep crop circles, aliens, and Atlantis.

Yet, it

was vivid. I had missed a bus for some reason and was running towards

home. I looked up and the volcano was off in the distance, the profile

very clear—more or less as I would see it from where I

live, both cones, Somma and Vesuvius, with the saddle-like depression

between them. Then, Vesuvius, the one on the right, started smoking.

Someone said, "Vesuvius is erupting!" and then the main eruption started—not

a slow, effusive eruption, but a cataclysmic explosion just like the

films I have seen of Mount St. Helens and Pinatubo, where the entire

top of the mountain explodes and then disappears behind the smoke.

I mentioned

the dream to a couple of acquaintances and they were reluctant to comment.

I think I may have trod on some unspoken rule that forbids talking about

such things. You never can tell. I am not sure if there is a time-limit

on the dream-lottery connection. This may take some research.

America's Cup (1)—

I

remember the town of Bagnoli as the degraded site of a steel mill, a

blight on the potentially beautiful Bay of Pozzuoli. The industrial

plant, of course, was ugly and dirty, and whatever recreational use

the waters might have served was rendered academic by the presence of

a huge industrial pier. I

remember the town of Bagnoli as the degraded site of a steel mill, a

blight on the potentially beautiful Bay of Pozzuoli. The industrial

plant, of course, was ugly and dirty, and whatever recreational use

the waters might have served was rendered academic by the presence of

a huge industrial pier.

As I have

noted in the log entry for Bagnoli, there is underway an enormously ambitious

project to revive the area. The steel mill is already gone, and an impressive

Science City exposition ground is, at least partially, already open

on the premises. The latest wrinkle in bringing Bagnoli back to life

is more ambitious than I could have ever imagined: The America's Cup!

—the boat race. (Not knowing anything about boats and sailing

except what I remember from Captain Blood, I am not even sure

if "race" is the proper term. I should be keelhauled, I know. Avast.

Belay that.)

The Swiss

team, Alinghi, won the recent 31st edition of the America's Cup in New

Zealand and is now searching around the Mediterranean for a site to

hold the 32nd competition in 2007, when they will be called upon to

defend the Cup. There are two Alinghi representatives now in Naples

to scout Bagnoli as a possible site, and there is intense politicking

going on at City Hall to get the race.

Palma di

Mallorca is also mentioned as a candidate. The Neapolitan papers, as

might be expected, tout all the advantages of Bagnoli, from wind conditions

to water depth to the availability of a vast tract of "virgin area"

to develop into facilities to accommodate the 18 craft that will participate.

I have seen the area, and—while there is nothing "virgin" about

it (I shall spare you the lame jokes about "restorative surgery")—much

of it is again available to be redeveloped. If selected, could they

do it four years? I don't think so.

(More

here and here.)

Castel

dell'Ovo (Egg Castle) (1)

The Castel dell'Ovo (the Egg Castle) is what you

first notice as you stroll along the seaside Villa

Comunale, the Communal Gardens, in Naples. It is a fortress built

on the small island of Megaride, just off the Santa Lucia section of

the city. Here, legend has it, is where the siren Parthenope

washed ashore after throwing herself into the sea when her song failed

to bewitch Ulysses.

Less mythologically,

here is where the Greeks from Cuma to the north first settled the bay of Naples

in the fifth century bc. Centuries later, the island became the home

of the last Roman emperor, exiled here in 476 A.D. after the empire

was overrun by the Goths.

[Various

sources say that the young, last emperor, Romulus Augustulus, was banished

to the "castle of Lucullus" in Campania by Odoacer, whom Gibbon, in

The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, called "...that successful

barbarian..." . Gibbon also says, however, that " When the Vandals became

formidable to the seacoast, the Lucullan villa, on the promontory of

Misenum, gradually assumed the strength and appellation of a strong

castle, the obscure retreat of the last emperor of the West." That is

almost certainly a mistake. There were imperial villas on the promontory

of Misenum, but the great villa of Lucullus (from which we derive the

expression, "To live in Lucullan splendor") was indeed on the island

of Megaride, where the Castel dell'Ovo now stands. The ex-last-emperor

was then apparently instrumental in founding a monastery on the island.

There are no reliable accounts of his last years or even of when he

died.]

The

fortress that you now see dates back "only" about a thousand years and

is essentially the result of Norman

and Angevin construction done in the Middle Ages.It was then that the

strange legend arose that a thousand years earlier, the poet

Virgil had hidden an egg in the castle, the fate of which would

parallel the fate of Naples, itself. As long as the egg remained intact,

the city would be spared destruction. Thus the unusual name, the Castel

dell'Ovo, or "Egg Castle". The

fortress that you now see dates back "only" about a thousand years and

is essentially the result of Norman

and Angevin construction done in the Middle Ages.It was then that the

strange legend arose that a thousand years earlier, the poet

Virgil had hidden an egg in the castle, the fate of which would

parallel the fate of Naples, itself. As long as the egg remained intact,

the city would be spared destruction. Thus the unusual name, the Castel

dell'Ovo, or "Egg Castle".

The egg,

of course, is in many contexts --from pre-Christian ones to Augustine's

commentary on Luke to Bosch's "The Garden of Earthly Delights" and even

to the popular use of the "Easter egg"-- a symbol of life, resurrection

and hope. Thus, the broken egg stands for spiritual death, and, thus,

at least once in the Middle Ages, a Neapolitan monarch had to go out

and assure the people that the egg had not broken. It was intact --and

Naples was safe.

(For a

more personal view of the Egg Castle, click here.) (Also see here.)

Bellini

(Piazza) (1)

Piazza Bellini is on via Costantinopoli, appropriately

a few yards from the music conservatory,

San Pietro a Maiella. The square is a point where many historical threads

of the city come together as they do in so many places in Naples. Bellini was one of the founders of Italian lyric

opera. He was born in Sicily in 1801, but came to study and compose

in Naples in 1819. The statue, the work of Alfonso Bazzico, shows the

composer above allegorical representations of Norma, Giulietta,

Amina and Elvira, four heroines of his operas. (At least those

smaller pieces of sculpture used to be there. Recently the city

decided to remove them, possibly to protect them from vandalism. There

is no word as to when, if ever, they are to be returned.) Piazza Bellini is on via Costantinopoli, appropriately

a few yards from the music conservatory,

San Pietro a Maiella. The square is a point where many historical threads

of the city come together as they do in so many places in Naples. Bellini was one of the founders of Italian lyric

opera. He was born in Sicily in 1801, but came to study and compose

in Naples in 1819. The statue, the work of Alfonso Bazzico, shows the

composer above allegorical representations of Norma, Giulietta,

Amina and Elvira, four heroines of his operas. (At least those

smaller pieces of sculpture used to be there. Recently the city

decided to remove them, possibly to protect them from vandalism. There

is no word as to when, if ever, they are to be returned.)

The square

is adjacent to a section (photo on right, below) of the original west

wall of the Greek city of Neapolis, the massive blocks still lying where

they were put in place four centuries before Christ. The wall ran the

length of what is now via Costantinopoli, and, presumably, if

you could tear up that street and tear down all the nearby buildings

and dig down a few meters, you would find the whole wall, portals and

all —in addition to making modern residents very unhappy.

The square

is also at the point along via Costantinopoli where the Spanish chose

to breach the original walls of the city in the first “modern”

expansion of Naples, in the fifteenth century, putting in place the

gate right across the street that now leads to Port’Alba and Piazza

Dante. There are two prominent buildings in Piazza Bellini. The first

is Palazzo Conca, on the composer’s left (not shown here), built

in 1488 and long considered one of Naples’ major repositories

of period furnishings and works of art, belonging, as it did during

its long history, to two of the city’s most important families,

the Concas and, later, the Orsinis.

Directly

across from the composer is the Palazzo Firrao (photo on left),

also known as Palazzo Bisignano, built in the 1500s. The Baroque

façade of the building is due to the facelift given the building

in the 1600s by the greatest Neapolitan architect of the age, Cosimo

Fanzago, whose other works in the city include the arched courtyard

within the monastery of San Martino and the chapel in the Royal Palace.

The façade

is ornamental in the extreme and is listed in a 1718 catalogue as one

of the "most conspicuous" in the city. Among other things, the façade

presents an array of statues of seven kings of Spain, ranging from the

15th century to Charles II (1661-1700).

Today,

the square is a gathering place and watering hole for whatever passes

as a ‘Bohemian’ element these days. It is, as noted, right

next door to the music conservatory—and

right down the street from the Royal Art Academy on via Costantinopoli.

Music shops, coffee houses and art galleries abound, and there is an

open-air antique fair on Sundays. (Also, see

here.)

Trains

(1), metropolitana (5)

I

had been holed up at the Piazza Garibaldi stop beneath the main

railway station in Naples waiting for the Metropolitana for quite

some time. Still no train. The passengers—or, better, the ticketholders

who aspired to passengerhood—reacted variously. Some shuffled

helplessly like bored cattle. Others looked like zombies playing hopscotch,

stiffly lumbering up and down the platform, their eyes vacantly reflecting

the long dark perspective of the empty tunnels. Many of them looked

used to this ritual. They looked tough. They looked like Donner Party

Survivors. I moved away from them, down to the farthest end of the platform.

If The Night of the Living Dead Metro Riders broke out, I would

escape into the tunnel itself. (I made a mental note to avoid the fate

of those poor souls who had perished in the Great Late Train Riots of

The Week Before when they had become enmeshed in the cobwebs that crisscrossed

the tracks.) I

had been holed up at the Piazza Garibaldi stop beneath the main

railway station in Naples waiting for the Metropolitana for quite

some time. Still no train. The passengers—or, better, the ticketholders

who aspired to passengerhood—reacted variously. Some shuffled

helplessly like bored cattle. Others looked like zombies playing hopscotch,

stiffly lumbering up and down the platform, their eyes vacantly reflecting

the long dark perspective of the empty tunnels. Many of them looked

used to this ritual. They looked tough. They looked like Donner Party

Survivors. I moved away from them, down to the farthest end of the platform.

If The Night of the Living Dead Metro Riders broke out, I would

escape into the tunnel itself. (I made a mental note to avoid the fate

of those poor souls who had perished in the Great Late Train Riots of

The Week Before when they had become enmeshed in the cobwebs that crisscrossed

the tracks.)

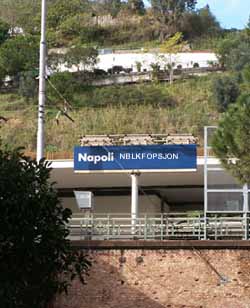

I saw that

I had moved right below the mechanical notice board. It had letters

that flip into place to indicate the destination of the next train.

I watched as the letters for my direction clicked over and spelled out,

'P–O–Z–Z–U–O–L–I'. That was

where I was going, so, in spite of whatever other character defects

it may have had, this was a good sign, though perhaps a mite optimistic,

for time continued to pass, time during which, I feel sure, the Great

Red Spot on Jupiter made significant progress across the surface of

that kingly sphere, but also a period during which our Metro station

remained as unsullied and pristine, as gloriously trainless as the Garden

of Eden.

My central

nervous system was now so bored that it threatened to start answering

weird ads in personal columns on its own just for a little action, so

I shifted over a bit and casually, unsuspectingly, looked up at the

other side of the board, the side that would indicate the destination

of trains going the opposite way. It, too, had tiny individual slots

for letters, but they were rightfully blank, since there was only one

more stop in that direction to the end of the line, Gianturco, which

was, however, closed for repairs. A strange thing then happened, something

that made my skin crawl. The sight of my skin slithering towards them

from the far end of the platform was so repulsive to the other passengers

that now they moved further away from me. Above me on the board, concealed

from them, but clear to me, the blank letter spaces had whirred to life

and where there should have been nothing, no destination at all, letters

had slowly flip–flopped into place and now read: 'NBLKFOPSJON'.

It was

only there for a few seconds and I was the only one to see it, but I

am now convinced that Someone or Something somewhere, for reasons that

may never be known, had given me a brief glimpse into The Other Side.

For those few short seconds, I, alone, on this planet knew the answer

to The Question: Where the Hell is My Damned Train?! It was in NBLKFOPSJON.

Everyone's unarrived train is in NBLKFOPSJON! Now it is clear—that

is the only place they could ever be! Surely you don't think there is

room for all the missing trains in Naples to be hiding out down at the

end of the line, maybe catching a quick beer and a smoke or listening

to the ball scores, while you cool your heels. They are clearly somewhere

else. NBLKFOPSJON is a—call it a 'station,' if you will, since

our language has no real term for places like this—that lies beyond

the end of the line. Perhaps it is a station in a universe parallel

to our own, or maybe—I haven't quite got all the details worked

out, yet—it is out near those isles of gloom, at the mere mention

of which even the bravest mariners in Viking sagas tremble and reach

for the glühwein—abodes with names like Fyrlswørth,

Llygymmkin, and, yes, Nblkfopsjon.

I'm not

sure what good this knowledge does me. It is almost masonically arcane—indeed,

there must be others out there who "know," and it has occured to me

that maybe we should have some way of making ourselves known to one

another—secret handclasps or something. Occasionally I test this

out by quite audibly ordering a metro ticket for "Nblkfopsjon" and then

quickly checking around me in the line for reactions. I thought I saw

a gleam of "knowledge" in the eyes of a young woman the other evening,

but when I ran over and tried what I thought was a pretty good secret

handclasp on her, she hit me in the nose. So, what have I learned? Maybe

this: don't fall asleep on the train.

Museum,

National Archaeological

The

National Archaeological Museum is located at the corner of via

Foria and via Costantinopoli. That point was also the northwest

corner of the original Greek wall of the city of Neapolis, remains of

which can be seen further down via Costantinopoli at Piazza

Bellini. It is a fitting site for one of the most complete collections

of Greek and Roman antiquities in the world, and one of the few places

where they can be viewed side by side just a few yards from precisiely

that outside world where they, indeed, existed side by side for centuries. The

National Archaeological Museum is located at the corner of via

Foria and via Costantinopoli. That point was also the northwest

corner of the original Greek wall of the city of Neapolis, remains of

which can be seen further down via Costantinopoli at Piazza

Bellini. It is a fitting site for one of the most complete collections

of Greek and Roman antiquities in the world, and one of the few places

where they can be viewed side by side just a few yards from precisiely

that outside world where they, indeed, existed side by side for centuries.

Charles

III of Bourbon founded the museum in the 1750s. He used a

building erected in 1585, one that had served as a cavalry barracks

and later, from 1616 to 1777, as the seat of the University of Naples. Expansion of the premises continued

in the latter half of the eighteenth century under the supervision of

Ferdinando Fuga and Pompeo Schianterelli. A final project drawn up in

1790 to complete the structure was never completed.

The museum

houses impressive collections from Pompei and Herculaneum; there are

exhibits from other archaeological sites throughout southern Italy,

including some from early non-Roman Italic peoples

of the area, such as the Samnites. More

recent additions include the Farnese collection and the Borgia collection

of Egyptian antiquities, this latter giving the visitor the bonus of

studying the very real commercial and social ties that the ancient

Greek city had with its own forerunner, Egypt.

Other collections contain items that in many other museums would be

considered much more than 'miscellaneous', such as the 'Tazza Farnese,'

one of the largest cameos in the world, crafted in Alexandria in 150

BC and that came into the possession of Lorenzo the Magnificent a millennium-and-a-half

later.

Capri

(3)

Looking

towards the "other end" of Capri-- Monte Solaro and Anacapri.

|

Like

the game that children and poets play, called "What do you see in that

cloud?" there's an experiment in visual perception in which you look at

an apparently random jumble of light and shadow, and try to pick out a

figure—perhaps a human face or an animal—"hidden" in the picture.

You can examine it for hours in vain, then the next day glance at it casually

and have it spring out at you like a jack-in-the-box. Then, you might

blink your eyes, look again—and it's gone. Like

the game that children and poets play, called "What do you see in that

cloud?" there's an experiment in visual perception in which you look at

an apparently random jumble of light and shadow, and try to pick out a

figure—perhaps a human face or an animal—"hidden" in the picture.

You can examine it for hours in vain, then the next day glance at it casually

and have it spring out at you like a jack-in-the-box. Then, you might

blink your eyes, look again—and it's gone.

Capri is like that. I have been looking at her profile daily for many

years from across the bay in Naples. "Her," because many claim to see

the head of a woman in the profile of Monte Solaro. Her hair

is flowing down to rest on the waters and her face is raised heavenward

as she stares off into space, perhaps playing her own games with the

clouds drifting overhead. Sometimes I see her, sometimes I don't. Perhaps

it is good that she is not always there at my beck and call.

But, whether

or not I manage to catch that glimpse of her, whenever I need a long

walk and peace and quiet, she—the island—is always there.

Strange, you say, to think of Capri in terms of solitude? Is this not

the Isle of Pleasure, boasting centuries of tales and descriptions of

lurid Hedonism? And even if you aren't a sinner, is there not an almost

obligatory hustle and bustle forced upon the visitor? How do you find

the peace and quiet.

The

"Natural Arch" on Capri

Walk. It's

amazing how long it took me to realize that. I was staring at Capri

from a short distance offshore and I remember seeing for the hundredth

and yet the first time the houses that dot the isle. I then realized

that I had no idea how all the people who live in those houses get about

when, except on a few principle roads, there is virtually no motorized

traffic at all. I set off to find out, and I discovered an extensive

network of trails, spun like a web over the island. Walk. It's

amazing how long it took me to realize that. I was staring at Capri

from a short distance offshore and I remember seeing for the hundredth

and yet the first time the houses that dot the isle. I then realized

that I had no idea how all the people who live in those houses get about

when, except on a few principle roads, there is virtually no motorized

traffic at all. I set off to find out, and I discovered an extensive

network of trails, spun like a web over the island.

I have

walked up from the Marina Grande to the top of Monte Solaro

in the midst of the tourist season and had the entire trail

to myself. I've hiked up to the Saracen Tower on Mount Barbarossa and

practiced the trombone, much to the amusement of the wildlife. I've

wandered down from the top of Monte Solaro to the small observatory

and to the church that commands the heights overlooking the town of

Capri, itself. I've hiked down the steps from Villa Fersen to

the sea and had a secluded bath in the sea, again at the height of summer

with not a soul in sight. Up to the villa of infamous Tiberius, down

to the Natural Arch, over to the red bunker that Malaparte called "home,"

down the via Krupp, and simply nowhere in particular along the

trails around Anacapri—the variations are endless.

Oplontis

Greek historian and geographer,

Strabo (63 BC – 24 AD), wrote that the stretch of Italian coast

from Cape Miseno to Sorrento—the Gulf of Naples—seemed a

single city, so strewn was it with luxurious villas and suburbs of the

main city of Naples. The eastern end of the bay, before the land swings

out to form the Sorrentine peninsula, is of course known today as the

site of two towns that met their doom in the great eruption of Vesuvius

in 79 a.d., Pompeii and Heculaneum. Greek historian and geographer,

Strabo (63 BC – 24 AD), wrote that the stretch of Italian coast

from Cape Miseno to Sorrento—the Gulf of Naples—seemed a

single city, so strewn was it with luxurious villas and suburbs of the

main city of Naples. The eastern end of the bay, before the land swings

out to form the Sorrentine peninsula, is of course known today as the

site of two towns that met their doom in the great eruption of Vesuvius

in 79 a.d., Pompeii and Heculaneum.

There is

a third, lesser–known, and little–excavated town: Oplontis.

It lies beneath the modern–day town of Torre Annunziata, such

a short distance from Pompeii that it was almost certainly a suburb

of that larger town and—according to recent archaeological thinking—probably

the port for Pompeii, so close is it to the sea.

The only

large, significant excavation at Oplontis is the "Villa of Poppaea,"

referring to Poppaea Sabina, Nero's second wife. That is at least a

possible conclusion from an amphora fragment bearing the name "Secundus,"

one of Poppaea's servants. In any event, it was almost certainly an

imperial residence, opulently equipped as it was with a 60 x 15-meter

swimming pool, a large number of rooms, intervening gardens and courtyards,

and murals on the walls that are still splendid. Some of the extant

murals are beautiful examples of the so-called "second Pompeian style,"

depicting artificial architecture on the walls—painted windows

opened onto painted sea or landscape or ontopainted rows of columns

that fade away from the viewer through the use of perspective, all to

give the illusion of space. It was, no doubt, one of the villas that

impressed Strabo so much.

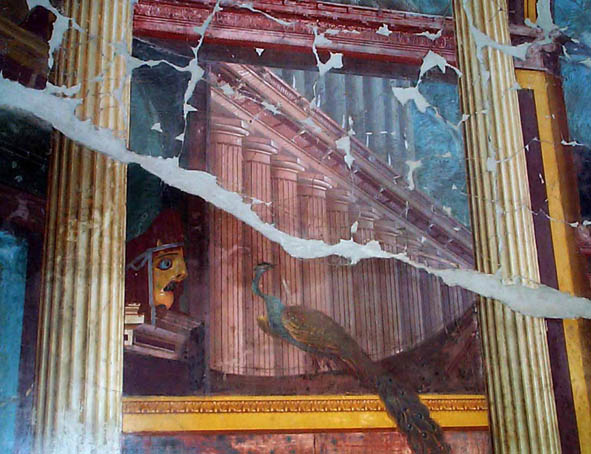

The

"peacock mural" from Oplontis. It is remarkable for the use of pseudo-perspective

in the columns and the trompe-l'oeil

effect of the bird's tail.

|

The

existence of such a regal residence is, in fact, noted in the Tabula

Peuteringiana, a medieval copy of a Roman road map. The villa and

whatever other structures made up the small town of Oplontis were buried

in the great eruption, however, and it wasn't until the 1500s that the

Spanish rulers of the Kingdom of Naples came across the ruins of the

villa while building an aqueduct. And it was not until the mid-1700s

that further excavation was undertaken in the same wave of archaeological

interest that spurred Charles III and then his son, Ferdinand IV, to

lay bare such antiquities as Pompeii and Herculaneum. Yet, Oplontis

remained—and remains—relatively unknown; the swimming pool

wasn't uncovered until the 1970s and the site, itself, was not open

to public visits until the early 1980s. The excavation is not complete

and never will be, since Oplontis, like Herculaneum, sits beneath a

modern town. To get into the site, you walk down a ramp until you are

at ground level, 79 a.d. (about 30 feet below the modern streets and

buildings that surround Oplontis). The

existence of such a regal residence is, in fact, noted in the Tabula

Peuteringiana, a medieval copy of a Roman road map. The villa and

whatever other structures made up the small town of Oplontis were buried

in the great eruption, however, and it wasn't until the 1500s that the

Spanish rulers of the Kingdom of Naples came across the ruins of the

villa while building an aqueduct. And it was not until the mid-1700s

that further excavation was undertaken in the same wave of archaeological

interest that spurred Charles III and then his son, Ferdinand IV, to

lay bare such antiquities as Pompeii and Herculaneum. Yet, Oplontis

remained—and remains—relatively unknown; the swimming pool

wasn't uncovered until the 1970s and the site, itself, was not open

to public visits until the early 1980s. The excavation is not complete

and never will be, since Oplontis, like Herculaneum, sits beneath a

modern town. To get into the site, you walk down a ramp until you are

at ground level, 79 a.d. (about 30 feet below the modern streets and

buildings that surround Oplontis).

By far

the most striking thing about Oplontis is what you don't find—human

remains. And there are no lava molds of people huddled together in death,

as there are at Pompeii. The Villa Poppaea was deserted when Vesuvius

erupted. In the wake of an earthquake that damaged the town and villa

severely in the decade before the great eruption, people had moved away

so reconstruction could take place. Presumably, the residents were elsewhere,

making typical complaints about how it took the Egyptians less time

to build the pyramids than it does for us Romans to put a few bricks

back in place, when real disaster struck.

|