©

2004 Jeff Matthews & napoli.com

Cilento,

National Park; monasteries (4)

Naples

is the name of the city as well as of the larger administrative unit—the

province—of which it is the capital. The province is, in turn,

part of the yet larger unit—the region—of Campania. The

province of Naples is not the largest in area in the Campania region,

however. That distinction goes to the neighbouring province of Salerno

to the south.

The province of Salerno occupies about 3,000 square

miles. About one-third of that area has been given over since 1991 to

the Cilento and Vallo di Diano National Park, an area of great natural

beauty and extreme historic interest. The park is almost all mountains

and starts just below Battipaglia, running down to Sapri on the coast

at the end of the Campania region. The bulk of the park occupies the

rugged terrain called "Cilento," a bulge on the coast that accommodates

a section of the Apennine mountain range that has wandered over from

the main line to drop off into the Tyrrhenian Sea. The province of Salerno occupies about 3,000 square

miles. About one-third of that area has been given over since 1991 to

the Cilento and Vallo di Diano National Park, an area of great natural

beauty and extreme historic interest. The park is almost all mountains

and starts just below Battipaglia, running down to Sapri on the coast

at the end of the Campania region. The bulk of the park occupies the

rugged terrain called "Cilento," a bulge on the coast that accommodates

a section of the Apennine mountain range that has wandered over from

the main line to drop off into the Tyrrhenian Sea.

That spur

of coast separates the Gulf of Salerno to the north from the Gulf of

Policastro in the south. Although the mountains are not high by the

absolute standards of the Alps (Monte Cervati at 1900 meters—5700

feet—is the highest summit in the Cilento), the relative height

is impressive, especially near the coast, where the immediate change

in altitude is from sea-level to the 1200 meters (3600 feet) of Monte

Bulgheria, a mountain that rises immediately from the coast above

and behind the town of Scario.

It is this section of the Cilento

that provides some fascinating glimpses into the history of Christianity.

If you stand in the little harbor of Scario, you look up at Monte

Bulgheria (photo, right)—an archaic Italian spelling for "Bulgaria"—Bulgarian

Mountain. It is in the middle of southern Italy but is so-called because

the area was settled by refugee monks from the east over 1000 years

ago. The great Iconoclast controversies of the 8th and 9th centuries

drove a number of monks to escape the severe persecutions of Constantinople

(indeed, the most severe of the "icon smashers" aimed to destroy monasticism,

itself). The monasteries founded in the immediate area of Monte Bulgheria

are Santa Maria di Pattano, San Giovanni Battista, San Marcurio di Roccagloriosa,

Santa Maria di Centola, San Nazario di Cuccaro, Santa Maria di Grottaferrata

in Rofrano, Santa Cecilia di Eremiti, San Cono di Camerota and San Pietro

di Licusati. All of them were founded between 750 and 950 a.d. It is this section of the Cilento

that provides some fascinating glimpses into the history of Christianity.

If you stand in the little harbor of Scario, you look up at Monte

Bulgheria (photo, right)—an archaic Italian spelling for "Bulgaria"—Bulgarian

Mountain. It is in the middle of southern Italy but is so-called because

the area was settled by refugee monks from the east over 1000 years

ago. The great Iconoclast controversies of the 8th and 9th centuries

drove a number of monks to escape the severe persecutions of Constantinople

(indeed, the most severe of the "icon smashers" aimed to destroy monasticism,

itself). The monasteries founded in the immediate area of Monte Bulgheria

are Santa Maria di Pattano, San Giovanni Battista, San Marcurio di Roccagloriosa,

Santa Maria di Centola, San Nazario di Cuccaro, Santa Maria di Grottaferrata

in Rofrano, Santa Cecilia di Eremiti, San Cono di Camerota and San Pietro

di Licusati. All of them were founded between 750 and 950 a.d.

The southern

Italian peninsula of the 700s and 800s was not a bad place for people

looking to be left alone. There were long periods when sections of the

south were under only the nominal control of a central authority. The

Lombards had invaded Italy late in the late 500s. In 800, they were

replaced by Charlemagne, the first Holy Roman Emperor, but even that

affected mostly central and northern Italy. In the 800s and 900s the

south stayed Lombard. First, it was the large Duchy of Benevento; then,

that splintered through civil war into smaller units, one of which was

the Duchy of Salerno. All of this was

then gobbled up in the 1000s by the Normans. Important for this brief discussion is

that Lombards, Salernitans, Normans—whatever—were all devout

followers of the western church. Yet, followers of the eastern Greek

church were, to my knowledge, pretty much left alone to worship as they

pleased, even after the schismatic movements from Constantinople, first

by Photius in 867, and, finally, the schism in 1054 that officially

separated Christianity into east and west. There was not then—nor

has there ever been in southern Italy—any particular persecution

of the Greek Orthodox religion by Roman Catholics. It is true, however,

that, little by little over the centuries, these eastern religious orders

in southern Italy became westernised and in many cases were simply absorbed

into the mainstream of the western monastic tradition.

Bruno,

Giordano (1548-1600) Bruno,

Giordano (1548-1600)

| "This

statue of Giordano Bruno stands in the square of that name in

the town of his birth, Nola, near Naples." |

Astronomy

became a modern science in the 16th and 17th centuries, largely through

the efforts of Copernicus and Galileo. It is less remembered than

it should be that the life's work of Nicolas Copernicus, De Revolutionibus

Orbium Coelestium Libri, containing his observations that the

Earth and all the planets revolved around the sun— though formulated

thirty years earlier— was not published until the year of his

death, 1543. Nick had a good head on his shoulders and that is precisely

where he wanted to keep it. Thus, he knew better than to go rip-snorting

through the streets of Unenlightenment Europe advising princes of

The Church that the Earth wasn't the center of the universe. Even

a century later, a very old, tired and beat up Galileo, understandably

afraid of the torture that awaited him unless he knuckled under, recanted

his blasphemous confirmation of Copernican heliocentricity.

Between

Copernicus and Galileo in time, we find the fascinating figure of

Giordano Bruno from Nola, near Naples. Unlike Copernicus, Bruno didn't

believe in soft-pedaling what he believed to be the truth. He was

flamboyant, vain and loud. He was also, most improbably, a monk for

eleven years of his young adulthood at the Franciscan monastery in

Naples before renouncing his vows in order to set off around Europe

as a wandering teacher of philosophy. And unlike Galileo, he not only

didn't fear torture and death, but his last words on the subject—literally

his last words on the subject, (spoken to his tormentors just after

they had sentenced him)—were defiant: "Perhaps you who pronounce

my sentence are in greater fear than I who receive it."

Giordano

Bruno still fascinates us today. (Indeed, even James Joyce used

to puzzle his friends by references to "the Nolan," and on occasion

paid homage to this fellow heretic and believer in the magical power

of words by using the pen-name "Gordon Brown"!) Bruno was caught, so

to speak, between two ages in our civilization. He was a mystic, a devout

man who brought with him from the past a belief in numerology, astrology

and alchemy and even an interest in the revival of ancient Egyptian

magic. He was, however, also a universal and tolerant man—one

who wanted the universe to make sense, and, in that, he was a forerunner

of the Age of Reason. He was, thus, ill at ease with the confining theology

of his day, which proclaimed the Earth the center of all things. He

believed in an infinite universe, a literal interpretation of the biblical

"worlds upon worlds," a universe in which nothing is fixed, not even

the stars, and where everything is relative, including time and motion,

a universe in which we are but a tiny part of the great unknown and

in which God becomes more of a universal mind, a substance inherent

in all things, not a personal, external Prime Mover. Unorthodox views

like this were to put him on a collision course with the Inquisition.

In the

early 1580s Bruno traveled to England where he lectured at Oxford and

met the great men of English letters, perhaps, they say, even Shakespeare.

Then, he left England and returned to France, Germany and back to Italy,

where he thought he would be able to convince the Inquisition that he

was no heretic and that his views were reasonable. He had, after all,

time and again as a monk apologized for his doubts and, now, before

the Inquisition, offered to defend his views. The Inquisition, of course,

was not interested in debate; they wanted penitence, and Bruno would

not give it to them. He spent eight years in prison, being "examined

and questioned". On February 19, 1600, he was burned at the stake

in the Piazza de' Fiori in Rome.

Bruno was

no Copernicus or Galileo in the scientific sense. His vision of the

cosmos was not based on puzzling over the apparent retrograde orbit

of planets or on observations through telescopes. His was more of a

philosophical, aesthetic stance. In order to make sense, the universe

had to be greater, infinitely greater, than his contemporaries imagined.

Or, in his own words (from De la Causa, principio et uno):

| This

entire globe, this star, not being subject to death, and dissolution

and annihilation being impossible anywhere in Nature, from time

to time renews itself by changing and altering all its parts.

There is no absolute up or down, as Aristotle taught; no absolute

position in space; but the position of a body is relative to that

of other bodies. Everywhere there is incessant relative change

in position throughout the universe, and the observer is always

at the center of things. |

Murat,

Gioacchino

(1767-1815)

The

shortest-lived dynasty to rule the Kingdom of Naples in its long history

was the one installed by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1806. It was the second

time in less than a decade that the French had "liberated" Naples

from the Bourbons. Earlier, in 1799, the forces of the revolutionary

French Republic had set up and shored up the Pathenopean Republic

in Naples; however, this sister republic to the south lasted a mere

six months before the Bourbon rulers returned from Sicilian exile

to restore their monarchy. The

shortest-lived dynasty to rule the Kingdom of Naples in its long history

was the one installed by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1806. It was the second

time in less than a decade that the French had "liberated" Naples

from the Bourbons. Earlier, in 1799, the forces of the revolutionary

French Republic had set up and shored up the Pathenopean Republic

in Naples; however, this sister republic to the south lasted a mere

six months before the Bourbon rulers returned from Sicilian exile

to restore their monarchy.

In 1806,

however, France was firmly in the hands of Napoleon, who, this time

around, was taking no chances. He chased the King and Queen of Naples

back to Sicily and installed his own brother, Joseph, as King of Naples.

Two years later he moved Joseph over to the throne of Spain and installed

as King of Naples his sister Carolina's husband, Joachim (Gioacchino,

in Italian) Murat, a trusted military aide. Murat already had a reputation

as a daring cavalry leader, having distinguished himself in support

of the French Republic and, later, Napoleon's meteoric rise to power.

Murat's role in the Egyptian campaign (1798-99) and then in the battles

of Austerliz and Jena was heroic. His rule in Naples would last until

1815 and would produce sweeping political and social changes way out

of proportion to the few brief years involved.

The changes

that took place in Naples under Murat more or less paralleled the changes

in the rest of Europe brought about through the imposition of the so-called

"Napoleonic Code," a legal system as monumental in human history as

the codes of Hammurabi and Justinian, or the Magna Carta. In the Kigdom

of Naples, the Napoleonic Code dismantled the 1000-year-old social structure

of feudalism. It also instituted a civil service based on merit, one

through which even modest citizens of the kingdom could advance. Those

two items mark the beginning of an economic middle class—truly

the end of one age and the beginning of another. (It is important to

remember that in spite of Napoleon's ultimate defeat, these changes

helped shape subsequent European history.)

Murat also

revamped the former Bourbon military academy, the Nunziatella, so as to make the military less alienated

from the people. He encouraged citizens to avail themselves of military

careers and rise through the ranks. He, the king, himself, was the prime

example, having started life as the son of an inn-keeper. University

reform and the beginnings of scientific facilities such as the observatory

and the Botanical Gardens are all part of the innovations in Naples

under Murat. Physically, the city acquired broad new roads such as via

Posillipo and the boulevard leading from the National

Museum out to Capodimonte. (The original name of that splendid thoroughfare

was, fittingly, Corso Napoleone.) Additionally, the mammoth structure

in what is now Piazza Plebescito, the Church

of San Francesco di Paola, was begun under Murat. It was planned

to be but the beginning of an enormous civic center, a forum.

What most

fascinates about Murat, however, is not the social change he wrought

in Naples, substantial though that may be. It was his political ambition.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century the main actors in what is

termed the Risorgimento—the movement to unify Italy—Mazzini,

Cavour, Garibaldi, were still a generation

in the future. The first rumblings of the Risorgimento were already

being heard, however. The famous patriotic phrase of Italian patriots

in the 19th century, "We shall not be free until we are one,"

was borrowed from Vincenzo Cuoco, a Neapolitan

writer and social philosopher very active during Murat's reign. Additionally,

secret societies such as the Carbonari

first took hold in Italy in the south at the time of Murat;

their avowed aim was constitutional government and eventual unification

of Italy. Interestingly, Murat encouraged these groups, for he saw himself

as the fulfillment of their vision—he would be the unifier

and King of Italy!

Portrait

of Murat and his queen, Carolina (Royal Palace, anon.)

As grandiose

as such ambitions were, they were piddling next to those of his brother-in-law's,

who was worried about continents and not mere nations. Thus, Murat found

himself back at Napoleon's side, serving as valiantly as ever in the

Russian campaign of 1812. Concerned about his own Kingdom in Naples,

however, Murat returned in early 1813 and in spite of Napoleon's crumbling

foretunes—or maybe because of them—decided

to make his own move for posterity. He publicly distanced himself from

the Emperor and moved north in Italy, taking over the Papal States and

Tuscany, unifying a large portion of the peninsula on his own. All this

required signing a treaty with Austria, Napoleon's archenemy, a deed

which earned him the label of "betrayer" from the man who had put him

in power in the first place. As grandiose

as such ambitions were, they were piddling next to those of his brother-in-law's,

who was worried about continents and not mere nations. Thus, Murat found

himself back at Napoleon's side, serving as valiantly as ever in the

Russian campaign of 1812. Concerned about his own Kingdom in Naples,

however, Murat returned in early 1813 and in spite of Napoleon's crumbling

foretunes—or maybe because of them—decided

to make his own move for posterity. He publicly distanced himself from

the Emperor and moved north in Italy, taking over the Papal States and

Tuscany, unifying a large portion of the peninsula on his own. All this

required signing a treaty with Austria, Napoleon's archenemy, a deed

which earned him the label of "betrayer" from the man who had put him

in power in the first place.

Murat's

move was premature. Napoleon's defeat and exile to Elba meant the restoration

of the old European monarchies, and Murat was forced to cede his newly

acquired territory. He was not done, however. Napoleon's bold return

from exile gave Murat another chance. In March of 1815 he allied himself

once again with Bonaparte, agreeing to march north and hold a defensive

line against the Austrians to keep them from attacking France through

northern Italy. There is no way of knowing how Napoleon might have fared

if Murat had simply followed orders. Instead, he attacked the Austrians

and lost a major battle at Tolentino.

In the

six weeks between his own defeat on the battlefield and Napoleon's ultimate

defeat at Waterloo, Murat left the Kingdom of Naples in the face of

advancing Austrian troops. Murat's last proclamation to the people of

the Kingdom of Naples appears in the Giornale delle Due Sicilie (Journal

of the Two Sicilies) on May 18, 1815. He writes from San Leucio, near

Caserta. He warns against fearmongers and says, "The enemy is still

distant...but I shall never expose you to the terrors of warfare within

our capital [the city of Naples]." Then, in what amounts to a farewell,

says, "If destiny must strike, let it strike only me." With that, he

was gone. The newspaper appears a few days later on May 23, 1815. The

lead article is a proclamation from Ferdinand IV, welcoming himself

back to his kingdom and promising love and benevolence. It is

written from Palermo, Sicily, where he had weathered, for the second

time in 10 years, the storm of exile. He assumed the title of Ferdinand

I, King of the Two Sicilies (as opposed to Ferdinand IV, King of Naples).

His wife, Queen Caroline, had died in Austria in 1814. Ferdinand married again. He died in 1825, having ruled Naples—with

a few interruptions—since 1759.

Murat went

to Paris where Napoleon refused to see him. After Waterloo, Murat's

fate was sealed. His kingdom was back in the hands of the Bourbons and

there was nothing he could do about it. Yet, he still wasn't through.

This quixotic would–be king of a united Italy refused benevolent

offers to be put out to pasture and live out his days in peace. Instead,

he took a handful of men and landed at Pizzo on the coast of Calibria,

no doubt imagining himself rallying the local military forces and then

marching north to retake his kingdom. Instead, he was imprisoned and

sentenced to death. His appeals to Ferdinand, the restored King of Naples,

that you just didn't shoot fellow kings, fell on deaf ears.

On October

18, 1815, Gioacchino Murat, in a last typical display of bravado, refused

the blindfold and commanded his own execution. A second-hand account

of the episode is found in the The Nooks and By-Ways of Italyby

Craufurd Tait Ramage, which went through a single edition in 1868. (There

exists a scholarly edition, published in 1965 and 1987 as Ramage

in South Italy and edited by Edith Clay, Academy Chicago Publishers,

Chicago.)

[ Click here to read an excerpt from that source.]

A statue

of Murat was erected in the 1880s as one of the eight that line the

west facade of the Royal Palace in Naples.

Rossini,

Gioacchino

Biddy-bump,

biddy-bump, biddy-bump-bump-bump!

| Rossini's

residence in Naples was in the Barbaja villa (photo, below), across

from the main cable-car station on via Toledo (via Roma).

Domenico Barbaja (1778-1841), the owner of the building, was the

foremost impresario in the Naples of the day. He got Rossini to

come to Naples in the first place and also managed the rebuilding

of San Carlo after it burned in 1816. |

If

you saw that awkwardly-rendered musical pun at the top of this entry

and said, "Hey, I know that...," then you are living proof of the omnipresence

of Gioacchino Rossini’s music, even in the lives of those who

wouldn’t know an overture if one bit them on the bassoon. It is

strange, indeed, that we should be surrounded by the music of one whom

we have never quite taken seriously. If

you saw that awkwardly-rendered musical pun at the top of this entry

and said, "Hey, I know that...," then you are living proof of the omnipresence

of Gioacchino Rossini’s music, even in the lives of those who

wouldn’t know an overture if one bit them on the bassoon. It is

strange, indeed, that we should be surrounded by the music of one whom

we have never quite taken seriously.

I recall

a list of the world’s most popular classical composers, rated

by number of performances in concert halls around the world over the

last century. As might be expected, Beethoven is in first place. No

one is in second place and fading fast. Beethoven deserves it, of course.

If you take Michelangelo, Shakespeare and Einstein, and roll them all

up into one very very large musician, you get Beethoven. It is impossible,

for example, to play Beethoven’s 5th Symphony to death —although

many have tried. That’s how good it is.

On the

other hand, one notch or so down the list, at the level of mere mortal

composers who are only great, Rossini, too, gets a good workout,

especially if you count all the bits and fragments of stray Rossini

that wind up as background music on radio, TV and film sound tracks.

He wrote mostly operas, but concert-goers generally get

their Rossini in orchestral format, since overtures to operas

are often played as stand-alone symphonic works. Even total musical

morons can get theirs if they’re not careful, just by watching,

say, that magnificent Bugs Bunny cartoon where our wascally fwiend conducts

a fine, if somewhat truncated, version of the opening aria —the

silliest piece of great music ever written— of Rossini’s

opera, The Barber of Seville, (the lyrics read, approximately,

"Figaro, Figaro, Figaro, Figaro") until the Hollywood Bowl collapses.

And if you have really and truly never heard Biddy-bump, biddy-bump,

biddy-bump-bump-bump!— from the overture to the opera William

Tell—you should check your birth certificate; it’s a

fake—you don’t exist.

Rossini

was born in Pesaro in central Italy in 1792, the year Mozart died. It would thus be poetic justice if he

were remembered as some sort of a link between the perfect classicism

of Mozart and the passionate Romanticism of the early 1800s —in

short, if he had been Beethoven. That would have been difficult, however,

because Beethoven was already Beethoven at the time. Rossini comes down

to us, then, as a composer born a few decades too late. He said of himself

that he ‘was born to write Comic Opera,’ referring to the

school of Neapolitan farce that was the rage of Europe from 1750 to

1800. He, himself, is remembered as the last in the line of such composers,

the one who wrote the greatest of all such works, The Barber

of Seville. It was unfortunate for Rossini that he wrote at a time

when Europe was no longer interested in musical comedy. People wanted

passion and thunder—volcanoes of music. That was something Rossini

could not give them. Beethoven, of course, could and did. Rossini

was born in Pesaro in central Italy in 1792, the year Mozart died. It would thus be poetic justice if he

were remembered as some sort of a link between the perfect classicism

of Mozart and the passionate Romanticism of the early 1800s —in

short, if he had been Beethoven. That would have been difficult, however,

because Beethoven was already Beethoven at the time. Rossini comes down

to us, then, as a composer born a few decades too late. He said of himself

that he ‘was born to write Comic Opera,’ referring to the

school of Neapolitan farce that was the rage of Europe from 1750 to

1800. He, himself, is remembered as the last in the line of such composers,

the one who wrote the greatest of all such works, The Barber

of Seville. It was unfortunate for Rossini that he wrote at a time

when Europe was no longer interested in musical comedy. People wanted

passion and thunder—volcanoes of music. That was something Rossini

could not give them. Beethoven, of course, could and did.

Yet, Rossini

is one of the five composers who have defined Italian opera over the

last 200 years in terms of quality and quantity of their work, their

popularity and their critical acclaim. Working backwards chronologically,

these composers are: Puccini, Verdi, Donizetti, Bellini and Rossini.

Puccini is the undisputed master of the late Romantic Italian opera,

a composer with an uncanny flair for couching tragedy in beautiful

melody. Then, Verdi’s career overarches almost the entire history

of 19th-century Italian nationalism, and his music is inextricably bound

up with the struggle to create a unified nation during that period;

he was a patriot as well as a musician. Donizetti

and Bellini, contemporaries, mark the beginnings

of Italian lyric romanticism in music: love, passion, heroism, all to

the sounds of beautiful melody—now the trademark of Italian opera.

Then comes Rossini, the last great Italian composer of the 1700s—

which is strange to say, since he lived until 1867. Indeed, he was called

the "grand old man of Italian music" by Verdi, whom everyone else called

the "grand old man of Italian music."

Rossini

was a child prodigy, performing at the age of 12 as a pianist and soprano

singer. In 1815, at the age of 23, he was appointed "house composer"

and musical director of the San Carlo theater

in Naples. He served in Naples for seven years, during which time he

composed some of his best–remembered works. One of these was The

Barber of Seville. The scandal surrounding the opening of that work

is well-known. An opera by that name already existed in the repertoire

of Neapolitan comic opera, and it was extremely popular. Rossini decided

to write another one, thus incurring the wrath of Neapolitan fans of

Giovanni Paisiello, the composer of the original.

Said boors showed up at the premiere in Rome and disrupted the performance;

they say that even members of the cast conspired to make the premiere

a flop, which it was—an utter and total flop, getting catcalls

and walk-outs all evening and leaving Rossini almost suicidally depressed

by evening’s end.

A caricature

of the day has fun with the exuberance of Rossini's music.

The

fact that Rossini did not take failure lightly may have been at the

heart of his decision at the ripe old age of 37 in 1829 to stop composing

opera altogether. His last opera, William Tell, starts with the

overture that "everyone remembers". It is perhaps the most overplayed

piece of music in the entire classical repertoire. Indeed, at least

in the United States, where the overture was for years the theme music

of the popular radio and TV western series, The Lone Ranger,

it is said that the only ones who can hear the music and not think of

horses and Cheerios (the sponsor) are intellectuals —and

they're lying. Yet, in spite of that, it remains a magnificently

stirring piece of music and still has the power to move. Rossini wrote

William Tell as somewhat of an answer to critics who told him

that the age of the comic opera was over and that he should start generating

a little true fire. William Tell is, thus, Rossini at his most

passionate. It was the most Romantic, stirring, and deliberately 19th-century

piece of music he could wring out of his 18th-century soul. It didn’t

flop, but it wasn’t a smash hit, either. The

fact that Rossini did not take failure lightly may have been at the

heart of his decision at the ripe old age of 37 in 1829 to stop composing

opera altogether. His last opera, William Tell, starts with the

overture that "everyone remembers". It is perhaps the most overplayed

piece of music in the entire classical repertoire. Indeed, at least

in the United States, where the overture was for years the theme music

of the popular radio and TV western series, The Lone Ranger,

it is said that the only ones who can hear the music and not think of

horses and Cheerios (the sponsor) are intellectuals —and

they're lying. Yet, in spite of that, it remains a magnificently

stirring piece of music and still has the power to move. Rossini wrote

William Tell as somewhat of an answer to critics who told him

that the age of the comic opera was over and that he should start generating

a little true fire. William Tell is, thus, Rossini at his most

passionate. It was the most Romantic, stirring, and deliberately 19th-century

piece of music he could wring out of his 18th-century soul. It didn’t

flop, but it wasn’t a smash hit, either.

Rossini

lived the last half of his life in France and never wrote another opera.

He composed some sacred music, most prominent of which is the Stabat

Mater. He lived far into the 19th century, yet was viewed as a composer

firmly rooted in the music of the distant past. He did not have the

mysterious and revolutionary passions of Beethoven, or even the simple

flair for a beautiful melody, like his countrymen Bellini or Donizetti.

By the calendar, he was a contemporary of the two giants of 19th century

Romantic opera, Verdi and Wagner; yet, compared to them musically, he

was truly a time traveler—and if he could not get back to the

past, he did the next best thing: he quit composing opera and let the

world of music go forward without him.

Rossini,

however—this person "born to write Comic Opera," and whose music

seems so light-weight to our ears—was esteemed by his contemporaries.

Verdi’s famous Requiem was originally conceived by Verdi

to be a joint effort by himself and other Italian composers to honor

Rossini on his death in 1867. The work went unfinished at the

time and was reworked by Verdi and ultimately performed as a requiem

mass for the author Alessandro Manzoni in 1875. Rossini, thus, never

got the honor which he was due. In a sense, he is still waiting.

De

Crescenzo, Luciano

Without

calling up a lot of publishers to make sure, I'm guessing, but I'd say

that the most popular living Neapolitan author is Luciano De Crescenzo.

He was born in 1928 in Naples, got a degree in engineering and went

to work for IBM in Rome. Just shy of his 50th birthday, he decided to

write a book about Naples, Così Parlò Bellavista—accurately

rendered in the English translation ten years later (since it is a pun

on Nietzsche's Also sprach Zarathustra) as Thus Spake Bellavista.

The introduction contains a one-sentence summary of De Crescenzo's

philosophy: "Naples isn't simply a city; it is a part of the human spirit

that I know I can find in everyone, whether or not they are Neapolitan".

On the dust-jacket of one of his books—where the editor

tells you about the author—De Crescenzo sneaks in a few

lines in the third person: "He didn't do well at IBM because he was

always late...Those who don't like him call him a 'humorist'." Without

calling up a lot of publishers to make sure, I'm guessing, but I'd say

that the most popular living Neapolitan author is Luciano De Crescenzo.

He was born in 1928 in Naples, got a degree in engineering and went

to work for IBM in Rome. Just shy of his 50th birthday, he decided to

write a book about Naples, Così Parlò Bellavista—accurately

rendered in the English translation ten years later (since it is a pun

on Nietzsche's Also sprach Zarathustra) as Thus Spake Bellavista.

The introduction contains a one-sentence summary of De Crescenzo's

philosophy: "Naples isn't simply a city; it is a part of the human spirit

that I know I can find in everyone, whether or not they are Neapolitan".

On the dust-jacket of one of his books—where the editor

tells you about the author—De Crescenzo sneaks in a few

lines in the third person: "He didn't do well at IBM because he was

always late...Those who don't like him call him a 'humorist'."

When that

first book came out in 1977, he appeared as a guest on a popular Italian

talk-show. He was (and is) eminently likeable and unassuming, and his

new career took off. Since then he has written about 20 more books.

He has sold almost 20 million books in 25 different countries and 19

languages. Almost all of them are light-hearted looks at the human

condition, including "histories" or "stories" (the Italian word is the

same) of Greek philosophy, in the course of which he tells us that the

famous "Seven Sages" consisted of 22 different people. He tacks on his

friend, Peppino Russo, at the end of the list. De Crecenzo's style

is readable in a way that most Italian writing—even modern

popular Italian literature—is not. It is entirely conversational

in the same way that, say, Mark Twain is. In other words, you get the

impression that you are listening to a very intelligent person

talking about some serious matters that would have interested you all

along if they hadn't been styled in concrete all these years by other

writers. "Who are we?" he asks. "Where do we come from? Where are we

going?" and then, "And what have we gained or lost by being born one

sex and not the other?" (This from his book, Women Are Different.)

De Crescenzo,

besides writing books, has now collaborated on screenplays and appeared

in films, himself—where he is a total natural. I saw him

the other night in Lina Wertmueller's brilliant 1990 film version of

Eduardo De Filippo's 1959 play, Sabato,

Domenica, Lunedì. The film stars Sophia Loren as Rosa Priore,

the family matriarch who sets out on Saturday to buy the makings for

the ritual ragù—her magic ragout known

in all Pozzuoli—the big Sunday stew for the entire family.

That opening scene is hilarious. Loren orders her usual ingredients

in a machine-gun monologue that attracts first the attention of the

other 10 women in the butcher shop, then their friendly advice on how

to make a real ragù, and then, through a Laurel-and-Hardy-type

escalation, come the know-it-all suggestions, more suggestions to "mind

your own business," general verbal abuse, and, finally, physical violence.

This is all watched by two cops on the sidewalk, one of whom sums up

the situation: "They're making ragù."

The rest

of the play centers on the misplaced jealousy on the part of husband,

Peppino, played by Eduardo's son, Luca. This jealousy is directed at

the supposed alienator of his wife's affections, professor Ianniello,

played by De Crescenzo. Peppino vents his false accusations at the Sunday

dinner table, devasting eveyone, especially his wife. Monday is taken

up with resolution and reconciliation.

It is Eduardo's

fusing of Checkov and Strindberg: the failure to communicate plus the

battle of the sexes. Since the film is an adaptation of the play, there

is liberty with the dialogue, including the professor's (De Crescenzo's)

good-hearted shrugging off of the accusation, explaining to the husband

how we all get caught sometimes at either the "Apollonian or Dionysian

extreme"—the realm of calm intelligence or that of raging

emotion. Peppino just got caught at the Dionysian end, that's all. That's

the way Neapolitans are. That's the way everyone is. That sentiment

is 100% De Crescenzo: "Naples isn't simply a city; it is a part of the

human spirit that I know I can find in everyone, whether or not they

are Neapolitan."

Astronomy

(2), Mars

Sea-level astronomy is hampered by general atmospheric

haze and—especially in or near a big city such as Naples—light

pollution. Having said that, I am still tempted to run up to the new

store on Vomero, where they sell digital cameras, computers, digital

cameras, computers, and digital cameras and computers. I think I saw

a small telescope on a shelf a few weeks ago. I can't miss this chance

to see Mars as it—in the words of the great astronomer,

Percival Lowell—"blazes forth against the dark background

of space with a splendor that outshines Sirius and rivals the giant

Jupiter himself." Mars is at "perihelic opposition" and has not been

this close to Earth for 50,000 years. I recall working on a particularly

good drawing of a bison for the Lascaux Municipal Museum at the time. Sea-level astronomy is hampered by general atmospheric

haze and—especially in or near a big city such as Naples—light

pollution. Having said that, I am still tempted to run up to the new

store on Vomero, where they sell digital cameras, computers, digital

cameras, computers, and digital cameras and computers. I think I saw

a small telescope on a shelf a few weeks ago. I can't miss this chance

to see Mars as it—in the words of the great astronomer,

Percival Lowell—"blazes forth against the dark background

of space with a splendor that outshines Sirius and rivals the giant

Jupiter himself." Mars is at "perihelic opposition" and has not been

this close to Earth for 50,000 years. I recall working on a particularly

good drawing of a bison for the Lascaux Municipal Museum at the time.

I thought

I might be able to get something Neapolitan out of Mars—Marte,

in Italian. Maybe a good Neapolitan noodle—say, martellini.

("Man, that's some fine plate of martellini! Think I might get

the recipe?") If only…if only. Alas, martellino means "little

hammer". It is also a regional name of the bird called, scientifically,

the cisticola juncidis, the Fan-tailed Warbler. At least, I think

that's the English name, and if you had a fan-tail, wouldn't you

warble? I rest my case. I thought, too, that perhaps Giovanni Schiaparelli

(1835-1910) the astronomer who started us looking for "canals" on Mars,

might have been from Naples, but, no, he had to come from Savigliano,

not far from Cuneo, a town way up there west of Genoa. Cuneo has a folk-reputation

for turning out slow-witted people, of whom Schiaparelli was definitely

not one.

In any

event, most serious star-gazing in these parts operates out of the observatory

in the Apennines near Castelgrande, well east of Salerno. It is one

of the most important observatories in Europe and is run by the Naples

observatory. The Naples observatory, itself, is located on the Capodimonte

hill and has its roots in the—if not infinite, at least

benevolently despotic—wisdom of Charles

III of Bourbon; he endowed a Chair of Navigation and Astronomy at

the University of Naples in 1735. Actual construction of an observatory,

however, had to wait a while. During the French decade in Naples, Murat

approved the plan, and construction was started in 1812. The observatory

was completed after the Bourbon restoration and conducted its first

measurements in 1820.

The Naples

observatory has a 40 cm main telescope that, on occasion, is open to

the public. There is also a good library and museum of astronomical

artifacts. I see that on September 2 they will have a "Mars Party."

They will have missed the close encounter by a few days. (Gods of War

may come and Gods of War may go, but August vacation runs through the

31st.) Nevertheless, it will still be a good glance through the telescope.

The Naples

obervatory has a website at

http://oacosf.na.astro.it/

Ruffo,

Fabrizio; Pathenopean Republic (2)

Almost

totally unnoticed amid the clutter of modern buildings near the

port, this cross was set in place in 1799 to commemorate the reconquest

of the Kingdom of Naples by Ruffo's Army of the Holy Faith.

|

Cardinal

Fabrizio Ruffo (1744—1827) figures prominently in the history

surrounding the short-lived Neapolitan (or Parthenopean) Republic of

1799; he was the one who formed and led the loyalist Army of the Holy

Faith in its campaign to retake the kingdom of Naples from the forces

of the Revolution. Cardinal

Fabrizio Ruffo (1744—1827) figures prominently in the history

surrounding the short-lived Neapolitan (or Parthenopean) Republic of

1799; he was the one who formed and led the loyalist Army of the Holy

Faith in its campaign to retake the kingdom of Naples from the forces

of the Revolution.

He was

born at San Lucido in Calabria in 1744, son of Litterio Ruffo, duke

of Baranello. He was educated by his uncle, the cardinal Thomas Ruffo,

as a result of which he gained the favor of Giovanni Angelo Braschi

di Cesera, who in 1775 became Pope Pius VI. Ruffo became a member of

the papal civil and financial service and was created a cardinal in

1791, though he had never been a priest. He then went to Naples

where he was named administrator of the royal domain of Caserta. When

the French troops advanced on Naples in in December 1798, Ruffo fled

to Palermo with the royal family.

He was

chosen to head a royalist movement in Calabria with the goal of advancing

north on Naples and overthrowing the revolutionary government. He landed

at La Cortona on February 8, 1799 and began to raise the "Army of the

Holy Faith," organizing for his cause the aid of well-known Calabrian

bandits such as Fra Diavolo and Nicola

Gualtieri, known as "Panedigrano". It is impossible to find an impartial

statement about the conduct of Ruffo's army as it marched north. On

the one hand, he is described as somewhat of a Robin Hood, out to free

his kingdom from the French. On the other hand, he is said to have done

very little to prevent his bandit army from killing and pillaging as

they went. Supporters point to Republican atrocities, as well.

Perhaps all that can be said is that neither side was particularly interested

in taking prisoners. Whatever the case, by June, Ruffo's army had advanced

to the city of Naples. When the French army occupying the city in support

of the Republic withdrew to the north, the revolution was doomed.

Ruffo helped

broker the surrender of the city to his forces, guaranteeing safe passage

to those members of the Republican government who wanted to sail for

France. He was more interested in reconciliation than revenge. In a

letter to Admiral Nelson, dated April 30, 1799, he wrote:

| "If

we show that we want only to put on trial and to punish ... we

close the path to conciliation... Is clemency perhaps a fault?

No, some will say—but it is dangerous. I don't believe that,

and with some caution I believe it preferable to punishment."

Quoted

in Il Risorgimento Napoletano (1799-1860) Pironti, Lucio.

Collana Ricciardiana II. Libreria Lucio Pironto. Naples. 1993.]

|

Clemency

was not to be, and Ruffo was then genuinely outraged when his guarantee

was violated by the King of Naples, Ferdinand (certainly at the behest

of Queen Caroline), who had the refugees removed from ships in the harbor,

returned to prison, and put on trial. Ruffo, himself, was part of the

tribunal that was now to sit in judgment on the revolutionaries. He

was so inclined to be forgiving and lenient that the King removed him

from the tribunal.

[You

may read more about the Neapolitan Republic and events surrounding its

demise by clicking on

Eleonora Fonseca Pimentel; and

on The Bourbons (1).]

The French,

under Napoleon, retook the Kingdom of Naples in 1806 and stayed until

Napoleon's ultimate defeat almost 10 years later. Interestingly, Ruffo

stayed in Naples during the French decade. He apparently lived calmly

and undisturbed by the French, who might have had reason to act otherwise

toward their former enemy. When the Bourbons were again restored to

the throne of Naples, Ruffo took a ministerial post in the government

and again became a confidante of the same King, Ferdinand IV (now known

as Ferdinand I) whom he had aided so many years earlier. Ruffo

died in 1827 in Naples.

Giordano,

Luca (and the church of Santa Brigida)

The

church of Santa Brigida started out in the early 1600s to be a home,

a shelter for young women (called a "conservatory" in those days). It

evolved into a church named for the Swedish Saint, Brigida, said to

have visited Naples in the days of Joan I (the mid-1300s). The

church of Santa Brigida started out in the early 1600s to be a home,

a shelter for young women (called a "conservatory" in those days). It

evolved into a church named for the Swedish Saint, Brigida, said to

have visited Naples in the days of Joan I (the mid-1300s).

There are

two remarkable things about the church. The first is that it is still

standing. It is on via Santa Brigida, the rest of the length

of which constitutes the entire east flank of the mammoth Galleria Umberto. A number of buildings were razed

in the late 1880s when the Gallery was put up, but Santa Brigida was

spared. They simply built the new gallery around and over the smaller

church, causing some damage to it but essentially managing to save a

piece of history. History and art, that is—for the

art in the church is the second remarkable thing about Santa Brigida

and, no doubt, what saved it from the wrecking crews. The church contains

a number of works by—and also the tomb of—Luca Giordano

(1632—1705), the great painter of the Neapolitan Baroque.

Giordano

was, by most accounts, a child prodigy pushed along by his father, also

a painter. Giordano spent his formative years acquiring a reputation

for great speed and the uncanny abilty to copy the works of masters

such as Raphael and Michelangelo. As a result, he picked up amusing

nicknames such as "Hurry-up Luca", "Lightning" and "Proteus". He worked

throughout Italy for commission, including anonymous ones that had him

painting those ornate borders of mirrors and pieces of crystal. In 1687

he was invited to Spain by Charles II of

Spain (known as "The Little King" in Neapolitan lore), the last king

of the once mighty Spanish Empire. In 1687, of course, Naples was part

of that empire and was ruled from Madrid by a viceroy.

Giordano

returned to Naples in 1700, having become a very popular and very wealthy

painter in Spain. He spent the last five years of life helping struggling

artists in Naples. He was well liked and, artistically, he is still

highly regarded. He left many works throughout Italy and in Spain, but

a great number are in Naples. Besides the ones in Santa Brigida, his

Christ Expelling the Money Changers from the Temple is in the

church of the Girolamini (across the

street from the Naples cathedral) and the monastery (now museum) of

San Martino has some frescoes, including The Triumph of Judith.

Botanical

Garden

The Botanical Garden of Naples is another of the "green

lungs" in the city—those welcome, large patches of vegetation

that help the city breathe in the midst of asphalt and traffic. (Others

are the Villa Comunale, the Floridiana,

and the Vineyard of San Martino. ) The

Garden in Naples takes up about 30 acres and is located on via Foria,

adjacent to the gigantic old Albergo dei

Poveri, the poorhouse, and is part of the University of Naples

Department of Natural Science. It is one of the many scientific and

educational facilities instituted under French rule in Naples (1806-15).

(Another was the observatory.) The Garden opened in 1810 and had a

single director for the next 50 years. The Botanical Garden of Naples is another of the "green

lungs" in the city—those welcome, large patches of vegetation

that help the city breathe in the midst of asphalt and traffic. (Others

are the Villa Comunale, the Floridiana,

and the Vineyard of San Martino. ) The

Garden in Naples takes up about 30 acres and is located on via Foria,

adjacent to the gigantic old Albergo dei

Poveri, the poorhouse, and is part of the University of Naples

Department of Natural Science. It is one of the many scientific and

educational facilities instituted under French rule in Naples (1806-15).

(Another was the observatory.) The Garden opened in 1810 and had a

single director for the next 50 years.

At present

the Garden displays on the premises around 25,000 samples of vegetation,

covering about 10,000 plant species. Although open to the public, the

Orto Botanico is not, strictly speaking, a public park. It is

really an educational facility for the university and local high schools

and is separate from the agricultural department of the University of

Naples (on the grounds of the old Royal Palace

in Portici). The Garden is also actively engaged in the preservation

of some endangered plant species. There is also an ethnobotany section

of the Garden where plants are studied that are potentially useful,

medicinally, to humans. Besides smaller structures on the premises,

there are two larger ones: the 17th-century "castle," recently restored,

and the 5.000 sq. meter Merola Greenhouse. The castle contains lecture

and display rooms, and houses the ethnobotany section as well as the

fascinating section on paleobotany, displaying the evolution of plant

life throughout the history of our planet.

Matera

The Sassi

of Matera

Palimpsests were medieval documents that—in order

to conserve precious paper—were erased and then reused a number

of times. The erasures were not perfect and the older writings often

showed through, building up, layer by layer, a kind of ghostly record

of all that had gone before. Palimpsests were medieval documents that—in order

to conserve precious paper—were erased and then reused a number

of times. The erasures were not perfect and the older writings often

showed through, building up, layer by layer, a kind of ghostly record

of all that had gone before.

In a sense,

most of Southern Italy could be called an archaeological palimpsest.

The region of Basilicata (or Lucania) is a case in point. There are

still remnants of the ditch villages of pre-European peoples from 8,000

years ago. On top of this there are signs of early

Indo-European peoples such as the Oenotrians and the early Greeks

of Magna Grecia who displaced them in

the 8th century, b.c. This is mixed with signs of Italic tribes such

as the Lucanians, Oscans, and Samnites —all absorbed by the civilization

which was ultimately to leave its own indelible imprint across three

continents: the Romans. Then came the Lombards, Byzantine Greeks,

the Normans, the Angevin French, the

great Spanish realm of Charles V, (on whose empire "the sun never set"),

and so forth down to our own day when the area was taken up into a united

Italy.

Matera

is one of the two provinces of Basilicata; the capital city of the province

is also named Matera. The old part of this city of 50,000 inhabitants

is known the world over for its ancient urban complex, the Sassi.

Of all the kinds of dwellings we humans have built over the ages—our

huts, shanties, castles, hovels—nothing quite arrests the attention

as the sassi of Matera. Built on—into, really—both

sides of a gigantic limestone outcropping overlooking a deep ravine,

the sassi (meaning, simply, "stones") are a labyrinth of

cave–dwellings. The caves, themselves, were lived in without interruption

from the Neolithic (about 10 thousand years ago) until the 1960s and

are thus likely to be the oldest continually inhabited human settlement

in Italy.

The sassi

came into their own between the 8th and 13th centuries, a.d., when the

caves became a refuge for groups of monks persecuted in the Iconoclast

controversy that shook the Byzantine Empire. In Matera, these refugees

were isolated and safe in a no-man's land between waning Byzantine power

further south and unstable Lombard influence to the north. The monks

moved into the caves and built halls, sanctuaries and chapels. Later,

many of the cave dwellings were taken over by peasants as homes for

themselves and quarters for their animals. Over the last millennium,

houses have organically grown out of the original fissures and

caves (photo, above); steps, roofs and balconies have been added and

everything is arrayed in an irregular jumble, layer upon jagged layer,

roof to wall, balcony to doorstep, all so helter-skelter that the overall

impression is that of a beehive built by bees who don't like following

orders.

On a more

sombre note, writer Carlo Levi, upon seeing the sassi for the

first time, said he was reminded of his childhood visions of what Dante's

Inferno must have looked like: the descending layers spiralling

down into darkness and who knows what awful perdition—and when

the sassi were still inhabited, the thousands of candles glimmering

in the small windows at night might indeed have looked like fires burning

in hell. Levi's infernal vision notwithstanding, others have seen quite

the opposite in Matera. The strange combination of age and agelessness

about Matera lends it a Biblical quality, and here is where, in 1964,

director Pier Paolo Pasolini filmed his life of Christ, The Gospel

According to Matthew (and where, more recently, Mel Gibson filmed

The Passion of the Christ.)

The

entire complex is perhaps the most outstanding example anywhere in the

world of spontaneous rural architecture, yet the problems of great numbers

of people living at such close quarters were enormous. There have been

utopian claims that the 20,000 inhabitants living in the sassi

at mid–20th–century were a unique example of peasants, landowners,

shepherds, craftsmen, merchants and laborers living in social harmony.

The modern Italian state did not see things quite that way. It saw

an infant mortality rate of 43% (!) and a medieval folk magic that treated

ills by sprinkling the blood of a freshly slaughtered chicken on the

victim. The

entire complex is perhaps the most outstanding example anywhere in the

world of spontaneous rural architecture, yet the problems of great numbers

of people living at such close quarters were enormous. There have been

utopian claims that the 20,000 inhabitants living in the sassi

at mid–20th–century were a unique example of peasants, landowners,

shepherds, craftsmen, merchants and laborers living in social harmony.

The modern Italian state did not see things quite that way. It saw

an infant mortality rate of 43% (!) and a medieval folk magic that treated

ills by sprinkling the blood of a freshly slaughtered chicken on the

victim.

Laws were

passed during the 1950s to alleviate the overcrowded and unhygienic

living conditions. This meant moving most of the people out. New quarters

were built in the town of Matera, itself, and the sassi have

now essentially become empty shells, except for a small and strictly

limited number of inhabitants. The area has become—as well it

should—an object of tourist interest, and this has led to an ongoing

project to keep the houses, churches, villas, the small squares and

long flights of stairs of the sassi from deteriorating. Indeed,

the sassi have recently been added to the United Nations World

Heritage list of cultural artifacts worth preserving at all cost.

Aside from

the houses, themselves, there are in the area a great number of ancient

cave churches displaying Orthodox as well as Catholic ornamentation

within. Time and vandals have ravaged them to a certain extent, but

some original Greek icons on cave walls are still clearly visible

and venerable. Even traces of prehistoric habitation can be found within

some of the caves.

If you

want to actually buy one of the sassi dwellings and restore it, you

can do that, too, and get a 50% subsidy from the state! On the other

hand, if you just want to visit for a day, it's only a few hours south

of Naples on a fast autostrada.

I have

recently (April, 2004) had a kind letter from Elizabeth Jennings of

Matera, who tells me that "...A goodly portion of the Sassi are now restored

and the area is a beehive of activity, particularly in summer. Restaurants,

bars, pizzerie, salsa clubs...the streets hum with the sound of foot

traffic and voices...concerts and

plays...and a plan to convert a huge grotto into the Casa Grotta, a big cultural center. The human

overlay is very modern and young."

Sceneggiata

Operetta,

musicals, musical comedy, light opera, comedy opera—all of these

terms have been used at times in English since the early 1800s to describe

a form of musical theater in which there is spoken dialogue as well

as music; this, as opposed to simply "opera", in which even lines of

dialogue are sung, or at least talk–sung as recitativo.

This type of musical theater, mixing music and spoken dialogue, is also

generally shorter than, say, traditional Italian Classical and Romantic

opera and generally felt to be less serious and less ambitious, dramatically.

Many of the names associated with this mixed form of entertainment are

well known: Offenbach, Johann Strauss, Gilbert and Sullivan, Franz Lehar,

Victor Herbert, Rodgers and Hammerstein. Sometimes we remember only

the name of the person who composed the music, and sometimes we remember

both, even though we may not be sure who wrote what. It is conventional,

too, to group this music into "national schools"; thus, we speak of

the French opéra comique, Viennese operetta, English operetta,

American musical comedy, and Spanish Zarzuela. Operetta,

musicals, musical comedy, light opera, comedy opera—all of these

terms have been used at times in English since the early 1800s to describe

a form of musical theater in which there is spoken dialogue as well

as music; this, as opposed to simply "opera", in which even lines of

dialogue are sung, or at least talk–sung as recitativo.

This type of musical theater, mixing music and spoken dialogue, is also

generally shorter than, say, traditional Italian Classical and Romantic

opera and generally felt to be less serious and less ambitious, dramatically.

Many of the names associated with this mixed form of entertainment are

well known: Offenbach, Johann Strauss, Gilbert and Sullivan, Franz Lehar,

Victor Herbert, Rodgers and Hammerstein. Sometimes we remember only

the name of the person who composed the music, and sometimes we remember

both, even though we may not be sure who wrote what. It is conventional,

too, to group this music into "national schools"; thus, we speak of

the French opéra comique, Viennese operetta, English operetta,

American musical comedy, and Spanish Zarzuela.

There are

many local, regional versions of this kind of musical theater. In Naples,

it is called the sceneggiata. It is always sung and spoken in

Neapolitan dialect and generally revolves around domestic grief, the

agony of leaving home, personal deceit and treachery, betrayal in love,

and life in the world of petty crime. (If you get all of that in one

piece, then you may understand why I don't like it very much. I am allergic

to musical theater in which men bite their knuckles when they find out

they've been cuckolded, then stab the other man, disfigure the woman

involved, and break into song.)

The sceneggiata

started shortly after WWI, was extremely popular in the 1920s, faded,

but has been enjoying somewhat of a comeback with newer generations

of performers since the 1960s. It is, today, extremely popular in small

theaters and on local television.

What is

interesting about the sceneggiata is that besides the one focus

of popularity, Naples, the other main one is (or, at least, was) that

area of New York City known as Little Italy. That is not surprising,

given, one, the large Neapolitan and Sicilian population in the New

York of the early 20th-century and, two, the drama and trauma that naturally

spin off from the theme of immigration. (Indeed, one of the most popular

of all "Neapolitan Songs" comes from the tradition of the sceneggiata:

Lacreme Napuletane, composed in 1925 by Libero Bovio (lyrics) amd

Francesco Buongiovanni (music). It is the ultimate immigrant tearjerker

written in the form of a letter home to mamma in Naples at Christmas.

The writer is the immigrant son in America, who bewails being far from

home; the famous refrain begins, "How many tears America has cost us".

When one

says—as I did—that the song "comes from" the tradition of

the sceneggiata, that ties in with another interesting point about this

kind of musical theater: the relationship between an individual song

in the piece and the entire piece, itself. Most people who have seen,

say, American musical comedy, are used to the idea that songs are written

for a musical. That is, the story first exists in some form or

another and then a tunesmith and lyricist (on occasion, one person does

both) get together and knock out 7 or 8 songs for the production. (It

is also the case, however, that the plots are often weak; thus, the

musical will be forgotten while some of the songs become independently

famous. (Quick, what musical does "Someone to Watch Over Me," come from?

See?) In the sceneggiata, the opposite obtains: a song is written

and the theme is so potentially dramatic that writers then decide to

weave a plot around the song—basically, something for actors to

do until the main song comes along. The result is perhaps the same:

the individual song tends to outlive the larger dramatic framework.

In the

days when small neighborhood theaters were the main form of entertainment,

and when audiences were less sophisticated (or maybe just less jaded),

the sceneggiata evoked real passion among onlookers. I have some

friends who, even today, talk to the television, offering advice such

as "Watch out!" so I have no problem at all in believing that in the

1920s, fistfights used to break out in the audience during one sceneggiata

or another as people chose up sides in support of either the betrayed

husband or the unfaithful wife. (Even in straight Italian opera, Enrico

Caruso and company—in the tenor's very early career—were

once chased from the stage and through the streets of a small town near

Naples because the audience was scared out of its wits by the apparition

of the Devil in a production of Gounod's Faust.)

The most

popular sceneggiata ever written is probably Zappatore, (meaning,

exactly, "clodbuster," one who works the land and breaks up the soil

for farming) written as a song in 1929 by Bovio and Albano. It was then

spun out into a full-fledged stage production and even made into a film

on various occasions, the first actually from a film company in Little

Italy in New York. The most recent film version is the 1980 version

starring Mario Merola, easily the most popular performer of the Neapolitan

sceneggiata in the last 40 years and one whose considerable talents

have no doubt contributed to the staying power of the sceneggiata

in an age when it might have otherwise become passé.

The plot is typical: Hardworking Father—the Zappatore—sacrifices

to give Son an education. Said son promptly forgets his family and is

even embarrassed by their peasant presence. Etc. etc.

If you

think you have never seen a sceneggiata, you have seen at least

a small bit of one if you have ever seen The Godfather, part II.

There is a scene in which the young Vito Corleone (played by Robert

De Niro) is watching just such a production in a small theater in Littly

Italy. In the scene, a young woman bursts onto the stage and says "Una

lettera per te!" (A letter for you). The male lead then reads that

his mother in Naples has died, pulls out a pistol, and is about to shoot

himself. That is when the main plot in The Godfather, part II

moves on to something else, so we never find out what happened. I suspect

that the young man did not, in fact, blow his brains out, but simply

broke into song.

Virgil

in Naples (1)

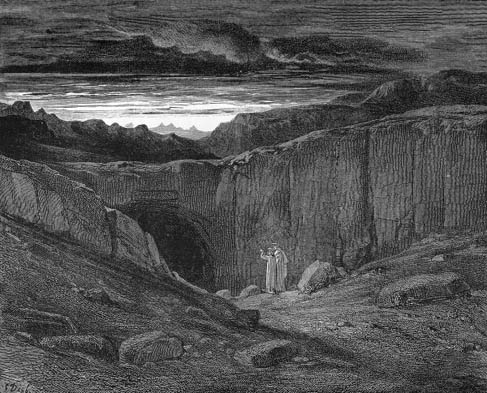

| One

of Gastave Dore's illustrations for the Divine

Comedy shows Vergil guiding Dante into the Inferno at

Lake Averno. |

Publius

Vergilius Maro (70-19 bc), one of the great names in Western literature,

is still connected in some slightly bizarre ways to modern-day Naples.

For example, if you drive past the Castel

dell'Ovo—the Egg Castle off of Santa Lucia and ask yourself

why it's called the "egg" castle, the answer is that about a thousand

years ago the rumor started that Virgil, a thousand years earlier,

had placed an egg in a small container on the premises. If the egg

was ever broken, disaster would befall the city. Indeed, egg shells

on the castle grounds were enough to cause small-scale disorder among

the population of Naples in the Middle Ages! Publius

Vergilius Maro (70-19 bc), one of the great names in Western literature,

is still connected in some slightly bizarre ways to modern-day Naples.

For example, if you drive past the Castel

dell'Ovo—the Egg Castle off of Santa Lucia and ask yourself

why it's called the "egg" castle, the answer is that about a thousand

years ago the rumor started that Virgil, a thousand years earlier,

had placed an egg in a small container on the premises. If the egg

was ever broken, disaster would befall the city. Indeed, egg shells

on the castle grounds were enough to cause small-scale disorder among

the population of Naples in the Middle Ages!

Another

one: if you drive through the Mergellina tunnel on your way to Fuorigrotta, you

pass within a stone's throw of a Roman tunnel. It was one of a few such

tunnels—all major feats of engineering at the time—that

the Romans built to get in and out of Naples. Legend has it that Virgil

conjured this one tunnel into existence by his powers of sorcery. The

Mergellina entrance to the tunnel is now on the premises of an historical

site called "Virgil's Tomb". And, three,

if you wander down to the seaside near Cape Posillipo, you can see the

paltry remains of what, over the centuries, has been called, The Sorcerer's

House—meaning Virgil.

Sorcerer,

you say? Isn't this the person who wrote The Aeneid? The

Bucolics? The Georgics? Indeed, it is, and he would probably

be amused at his putative powers of legerdemain —all due, by the

way, to the medieval Italian love of attributing magical ability

to the Greats of Antiquity. But when Virgil was alive, he wasn't yet

Antiquity; he was just great. No magic in great writing— just

hard work.

Virgil

was born near Mantua. His father was a prosperous farmer who sent his

son off to Rome to study. Virgil returned home to study Greek philosophy

and poetry on his own and began to write poetry that came to the notice

of Gaius Cilnius Maecenus, a friend and advisor to the young Octavius

(later to become "Augustus Caesar"). Maecenas' name has come down to

us as a metaphor of "patron of the arts". That reputation has largely

to do with his support of Virgil and the other great poet of the age

of Augustus, Horace.

Under the

patronage of Maecnas, Virgil published a collection of eclogues, idyllic

poetry, called Bucolica —"The Bucolics," in English. As

the title implies, they were filled with a spirit of nostalgia, a longing

for a simpler time. This was understandable when you consider that Virgil

was a young man when Julius Caesar was assassinated, an event that almost

tore Italy apart. That episode, itself, came on the heels of great unrest

during the previous 50 years in Italy. Rome was not yet the Roman Empire,

and events seemed to be coursing out of control. Perhaps, indeed, a

sensitive young poet might have thought—in different words,

perhaps, than it occurred to Yeats 2,000 years later—that "the

center cannot hold".

There are

ten pastoral poems in the Bucolica, one of which contains the

secret as to why Virgil was held in such high, magical esteem by Italians

in the Middle Ages. It is Eclogue number four, the so-called Messianic

Eclogue, in which Virgil predicts a new age of peace for the world,

ushered in by the birth of a child:

"Come

soon, dear child of the gods, Jupiter's great viceroy!

Come soon—the time is near—to begin your life illustrious!"

Medieval

Christian scholars saw this as a prediction of the birth of Christ and,

thus, held the poet to have been a "pagan Christian", if you will—one

in a position of privilege regarding the divine course of things. No

doubt, this is the reason Dante chose Virgil to be his guide through

Hell and Purgatory in la Divina Commedia—and no

doubt why, among all pagan authors, Virgil did not share their fate

of centuries of benign and even malign neglect by Christian scholars.

In any

event, Octavius prevailed, the empire geared up, and Virgil moved to

the Campania, to Nola, near Naples. Here Virgil wrote the Georgics

-- a hymn of praise to the farmer, another bit of nostalgia

about a simpler, happier time, full of hope that the new emperor, Augustus,

would be the beginning of a great reign of peace. The Georgics

are marked by an extraordinary upbeat ending, one of regeneration and

resurrection, told in the form of an optimistic allegory of new swarms

of honey-bees issuing forth from the carcasses of sacrificed cattle.

Here, at the end of the last Georgic, is where Virgil makes a

famous reference to Naples:

"This

was the time when I, Virgil, nurtured in sweetest

Parthenope, did follow unknown to fame the pursuits

of peace..."

Parthenope

was the siren in Greek mythology who gave her name to the first Greek

settlement in the Bay of Naples-to-be. Indeed, Neapolitans commonly

refer to themselves, even today, as "Parthenopeans".

Virgil

then set about immortalizing Augustus. Drawing on the form of

the Greek epic, he sang of Aeneas:

"...his

fate had made him fugitive; he was the first

to journey from the coasts of Troy as far

as Italy...

...until he brought a city into being...

from this have come the Latin race, the lords

of Alba, and the ramparts of high Rome..."

For Romans

of the day, the Aeneid was the epic summing up of their history

and a statement of their aspirations —this was to be The Roman

Empire. As with the Bucolica and the Georgics, Virgil

chose an earlier Greek model for his work: the Homeric epic form. Here,

it is interesting to note that all later epic poetry in the Middle Ages,

and even something as late as Paradise Lost (1667), owes more

to Virgil than to Homer. Until our own Renaissance had rediscovered

the Greeks, knowledge of the works of Homer was sketchy and anecdotal.

No one in Italy could even read classical Greek in, say, 1400, even

if they had had a Greek copy of the Odyssey, which they didn't.

Those Greek

originals (or, at least, copies of copies) would not be available for

another century and, thus, Latin translations of Homer were not completed

until the mid-1500s; so, the "epic" tradition, as originally Greek as

it might have been, passed into and through our Middle Ages and into

modern times as "Virgilian" rather than "Homeric". When Dante sat around

with his friends in 1300 talking about Homer —as he must have

done— he knew about Homer and mythical Troy only through references

in Roman writers, primarily Virgil, and through the veil of mythology,

one much more impenetrable to him than it is to us today. Homer and

Classical Greece must have seemed to Dante as, perhaps, tales

of Atlantis do to us, today. But Virgil? The entire Middle Ages knew

Virgil —he was on the bookshelf. They quoted his language; indeed,

they still wrote in Virgil's language, Latin, though, ironically,

it would be Dante, himself, to desert that language for the vernacular

form later to become known as "Italian".

Important

sections of the Aeneid play out in the area around Naples. It

is no problem at all, today, to walk up to the height of Posillipo where

Virgil must have stood. It was called Posillipo even then, so named

by Greeks centuries earlier —Pavsillipon, the "place where

unhappiness ends". From there you can look west across the Bay of Pozzuoli,

as Virgil must have looked as he struggled to put into poetry the mythology

and events that were ancient even to him. You see a point of land that

closes the bay at the other end. This is where Aeneas' comrade, Misenus,

master of the sea-horn—the conch-shell—made "the waves ring"

with his music and challenged the sea-god Triton to musical battle.

For his troubles, he was dashed into the sea and killed by "jealous

Triton". Then

"...Pious

Aeneas

sets up a mighty tomb above Misenus

bearing his arms, a trumpet, and an oar;

it stands beneath a lofty promontory,

now known as Cape Misenus after him:

it keeps a name that lasts through all the ages."

"All the

ages" is a long time, but at least 2,000 years later, it is still Cape

Miseno.

Right past

Miseno and the end of the bay, Aeneas and his men "glide to the Euboean

coast of Cuma"—"Euboean" from the Greek isle of "Evvoia", purported

home of those who had founded the city. Here

"...

you reach the town of Cumae

the sacred lakes, the loud wood of Avernus,

there you will see the frenzied prophetess

deep in her cave of rocks she charts the fates

... She will unfold for you...

the wars that are to come and in what way

you are to face or flee each crisis..."

This, of

course, is where Aeneas has come to get the answer he seeks —where

and whether the wandering Trojans will be able to rest. Here is the

cave of the prophetess, the Sibyl of Cuma:

"The

giant flank of that Euboean crag

has been dug out into a cave; a hundred

broad ways lead to that place, a hundred gates;

as many voices rush from these..."