©

2004 Jeff Matthews & napoli.com

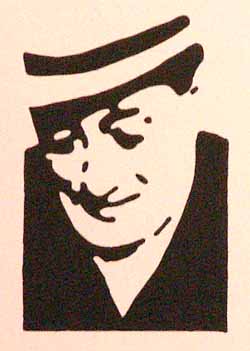

Caruso,

Enrico (1)

| This

small bust of Enrico Caruso stands in Piazza Ottocalli, not far

from the old Hospice for the Poor,

and about 50 yards from a very anonymous-looking building

where the great tenor was born. The house is marked by a plaque. |

If you like

rags-to-riches stories, you will find few as compelling as that of Enrico

Caruso (1873-1921). He was the youngest of twenty-one (!) children,

only three of whom survived infancy. Born into grinding poverty, he

was saved from the life of the scugnizzo

(street urchin) by two things: one, he went to work at the age of ten

in the factory where his father worked in Naples, and, two, even as

a child it was evident he could sing. By the end of his life, he had

become the highest paid singer in the world and was generally acknowledged

to be one of the greatest operatic tenors ever, a judgement that subsequent

history has had little reason to amend.

Even while

working as a lad, Caruso was encouraged by his mother, then his loving

stepmother, and a local parish priest to pursue his singing. He

joined a church choir and by his mid-teens was taking singing lessons

in his spare time and singing at every available opportunity, in cafès,

at weddings, even hiring himself out as a kind of singing Cyrano de

Bergerac, standing off to the side and singing for tone-deaf swains,

who would lip-synch and pretend to be serenading their lady loves.

He sang anything, anywhere and anytime, just to get experience.

Compared

to other singers of his day, Caruso's voice was a strange combination

of tenor and baritone. He had considerable trouble in his early career

with the high tenor register, for example, causing a number of early

teachers to tell him that he would never make it. The winds of cultural

change were blowing in his favor, however. By the 1880s the age of the

light, almost effeminate tenor was over; the new more realistic

operas of verismo (realism) such as I Pagliacci and Cavalleria

Rusticana called for an earthier male voice. In retrospect,

it is now obvious that Caruso's voice was the ideal vehicle for this

new kind of tenor vocalizing. And since Caruso has influenced every

tenor since him, even earlier operas, say by Bellini or Donizetti, undoubtedly

sound huskier today than they did when performed in the 19th century.

He started

his professional career in Caserta in 1895 and for the next few years

sang in the provinces and in various secondary operas in Naples —

but not at San Carlo, which was strictly

for stars. Playing in the Campania outback in those days was rough.

During one performance of Faust, in Caserta, the appearance of

the "devil" on stage so terrified the peasant audience that they shouted

the performance to a close and chased Caruso and the whole company off

the stage and through the streets with sticks and brickbats! Caruso

traveled abroad to Egypt, South America, and even Russia slowly building

his reputation. His "break" in Italy came in 1900 in Milan at La Scala,

by then the opera house in the world. He was a success.

Then Caruso

did something he had always wanted to do: he came back to Naples to

'wow' the hometown crowd at San Carlo. He undoubtedly envisioned coming

home in triumph, and if the public had had their way, maybe he would

have. Caruso, however, had neglected to butter up the right music critics

with invitations and tickets. Add to this the fact that his choice to

go to Milan first and then come south was seen by some as an affront

to Naples, only recently, and reluctantly, part of a unified Italy.

It had all the makings for a hostile reception —and it was, at

least on the part of the critics. So, although the public was generally

receptive to Caruso, the critics in the local papers panned him, saying

his voice was a hybrid of tenor and baritone, and that, dramatically,

he was uncouth. He sang in Naples in the winter of 1901/02 and then

left, bitterly disappointed, saying he would return to Naples only "to

see my mother and eat vermicelli alle vongole." He kept

his word and never sang again in the city of his birth. Whenever he

came home to visit, instead of giving a benefit performance for the

poor, he would simply donate to charity more money than even one

of his performances would have brought in.

(For

more on Caruso's critic and the offending review, see

here .)

He was

a generous, highly idiosyncratic, superstitious man. He refused to travel

on certain days of the week, or without consulting his astrologer; he

used home remedies for his vocal cords such as garlic and ether spray,

much to the dismay of his singing coaches; he smoked, drank and ate

to excess; and downed a large glass of whisky before going out on the

stage for his opening number at each performance. One of the strangest

stories about him is that, though caught in the great San Francisco

earthquake of 1906 and terrified like everyone else, he managed to calm

down enough to start singing in the corridors of his hotel. This

free performance by the Great Caruso had a calming influence amidst

all the confusion going on around him.

From 1903

until his death his home was the Metropolitan Opera in New York, during

which time he sang 622 leading roles. (That works out to 37 major

performances each season —phenomenal by today's standards!) His

stamina and vocal powers were legendary. On a few occasions, his natural

baritone register and perhaps his teenage experience as substitute serenader

came to the company's rescue, as Caruso would stand behind a set and

sing a baritone aria while the baritone, himself, with a headcold or

hangover, would move his lips and fake it!

Caruso

is at least partially responsible for the great popularity of the Neapolitan

Song abroad, as he would often include songs such as O sole mio

or Santa Lucia as encores after the opera at the Met. (This

practice of operatic tenors, Italian or otherwise, singing Neapolitan

Songs survives to this day; witness The Three Tenors.) As a Neapolitan

in America, his presence worked magic in the lives of the entire community

of his fellow "immigrants". Here was one who had made it, and through

him their own lives gained that much more hope for the future.

Caruso's

life combined poverty, incredible hard work, determination and,

ultimately, fame and wealth. He was a gifted artist, as well, and enjoyed

drawing caricatures of himself in various operatic poses. Indeed, his

life, itself, was a caricature of The Artist as Fatalist Disdainer of

Caution. He chose, instead, to ride his great talent as fast and as

far as it would take him. He died where he wanted to, at home in the

heart of Santa Lucia by the Bay of Naples. He was forty-eight.

Fortune

Tellers

Susi

stares out at us from the TV screen of a local Naples channel and says,

"Chiamatemi" --call me. She recites the phone number that also scrolls

across the bottom of the screen and then goes back to dealing cards

face-up on the desk in front of her as if she were cheating at solitaire.

Far from it. Suzi is engaged in cartomancy -- the telling of fortunes

from the cards. In the course of an hour or so, she gets a few calls

from people concerned about their love-life, jobs, health, etc. She

talks to them via a speaker-phone in the studio and then consults the

cards and gives advice. She is cheerful and friendly. Susi

stares out at us from the TV screen of a local Naples channel and says,

"Chiamatemi" --call me. She recites the phone number that also scrolls

across the bottom of the screen and then goes back to dealing cards

face-up on the desk in front of her as if she were cheating at solitaire.

Far from it. Suzi is engaged in cartomancy -- the telling of fortunes

from the cards. In the course of an hour or so, she gets a few calls

from people concerned about their love-life, jobs, health, etc. She

talks to them via a speaker-phone in the studio and then consults the

cards and gives advice. She is cheerful and friendly.

Generally,

Susi is what they call a "mago". The Italian term "mago" is a broad

one. Merlin was a mago. So was the stage magician and escape artist

Harry Houdini, and it is the word (cognate of the English term "magi")

for "Wise Men", referring to those who bore gifts to the Christ Child,

for they were said to be Zoroastrian astrologers, magicians from the

East.

Whatever

you call them --wizards, magicians, sorcerers, seers-- there are

still a lot of them around, and they do a land-office business, at least

in Italy. According to a recent article in the paper, there are 1,669

practicing maghi in Italy, and they command the trust and credulousness

of some twelve million Italians. That is, about one out of five Italians

is quite prepared to go to a mago and shell out anywhere from 15 to

100 dollars for a potion, spell, talisman, charm, amulet or incantation

-- anything to hocus-pocus away a problem. (I can't prove this, but

I suspect that the precentage in Naples is even higher. Magicians have

always had a solid place in Naples, going back to Virgil, who is said

to have concealed an egg on the grounds of what is today still called

the "Egg Castle". What happens if the egg breaks? You don't want to

know.) (See here for an entry on Virgil,

the mago's mago!)

My favorite

mago (and I want him to know this and to understand that I am not being

critical of him in any way, shape or form, and that I really think he

is a credit to his profession and species -- hey, my limbs are going

numb!) used to advertise his services on local TV.

My mago

X built his pitch along the lines of one of those South American

soap operas that take up so many valuable electrons in my television

set. It had (1) a beautiful and virtuous heroine, (2) a crisis brought

on by an evil rival, and (3) a resolution, this one effected, obviously,

by my main man, Mago. It had the same shaky home-video qualities as

the soaps and even went

in for the same lighting and those ultra close-ups that let you count

facial hairs choking and poking up through too much make-up like left-over

shrubbery from the mysterious Siberian fireball explosion of 1908. The

whole thing ran about ten minutes.

First we

saw mago in seclusion, perhaps at the sea-side or some mountain retreat,

but definitely a place on a higher plane, hidden from non-esoteric klutzes

like me, a good place with good vibes where you could meditate real

good. He would do that, staring into a campfire. There were plenty of

tight shots of his eyes to highlight their magnetic quality. The camera

was so close that at first you thought you were about to see a documentary

on glaucoma. The background music would start up; there were lots of

drums, letting you know that this guy was in tune with -- maybe even

in the same band as-- some very heavy voodoo hitters.

The plot

started. The heroine was a would-be ballerina. She was lovely, graceful

and kind. Career-wise, however, she was going belly up, for she was

about to be done out of the big lead role by her evil and less talented

rival, an envious wench with two left paws.

Heroine

then sees the very same ad that we are watching -- mago's blurb for

his "positively charged talisman"-- and calls the number

scrolling across the bottom of the screen (although I never could

figure out how she managed to read that number from her side of the

screen). Mago's secretary answers the phone, writes heroine's problem

down and takes it in to the Man. He then reaches in a drawer and pulls

out a talisman. It is unlike your and my talisman. Nothing bulky like

a rabbit's foot, bear paw, mandrake root, horse shoe, pyramid, pendulum,

animal horn or precious stone. This thing looks like a credit-card.

On one side is written "Health, Love, Business", and above that phrase

is the watchful and protecting all-seeing open eye common to much esoteric

tradition (as well as being on the unesoteric US one-dollar bill, right

above the pyramid). Mago then "positively charges" the talisman by pressing

it between his palms and mumbling over it. He sends it to Heroine and

as soon as she takes it out of the envelope and slips it in her purse

--lo and behold!-- the door to her dressing room opens and in comes

the producer of the big show; he has had a change of heart. She gets

the gig!

The story

is not finished, and this is the good part. Even after he sends Heroine

the magic credit card, mago somehow senses that all is not well. The

other dancer, Miss Bigfoot of 1997, is out to ambush our Goody Two-Shoes,

so mago rushes over to the theater, races backstage and --just

in time!-- pulls Heroine away from the path of a very large prop that

Evil Rival has cut loose, intending it to fall on and squash Goody as

flat as a positively charged credit-card-sized talisman.

The End.

Phew! Awesome. This reviewer has seldom seen such a persuasive restatement

of the non-discursive contingencies of the ontological argument, such

breadth of expression, such depth of emotion, such length of body parts.

Besides, how many wizards do you know who make house calls? (Hey, my

limbs are going numb!)

Ranieri,

Massimo

One

of the best- selling CDs in Italy at the moment is Oggi o dimani

by the Neapolitan singer/actor Massimo Ranieri. He started out more

than 30 years ago singing Neapolitan songs for the local market; then,

he won the Italian Song Festival in San Remo in the early 70s and since

has had a very solid career both as a singer and film actor. One

of the best- selling CDs in Italy at the moment is Oggi o dimani

by the Neapolitan singer/actor Massimo Ranieri. He started out more

than 30 years ago singing Neapolitan songs for the local market; then,

he won the Italian Song Festival in San Remo in the early 70s and since

has had a very solid career both as a singer and film actor.

This recent

CD takes advantage of the typically oriental flavor of much Neapolitan

music, a sound due to that erratic Middle-Eastern "quiver" in

the voice that almost all Neapolitan singers use -- a sound traceable

to the Spanish and, hence, Moorish influence in southern Italy. As well,

much Neapolitan music employs chromatic elements of Middle Eastern

scales. In addition to all that, Ranieri chose to record the numbers

using a background of Greek and Middle-Eastern instruments, including

the mandolin-like bouzuki, and a variety of North African percussion

instruments. Indeed, one number features another singer doing a verse

in his own North-African native language. Thus, a century after they

were written, these songs --often with texts by great Neapolitan dialect

poets such as Salvatore di Giacomo ("Napulitanata" and "Marechiare")

have taken on a refreshingly "new" sound -- but one that actually

works quite well.

Jewish

community, language/s (1), Yiddish (1)

There

is such an exotic abundance of languages on the busses in Naples these

days that you feel as if you have wandered into a workshop run by the

Summer Institute of Linguistics, those busy language beavers of bible

translation who tell us (at www.sil.org),

for example, that there are 8 languages spoken in Sri Lanka, 8 in the

Ukraine, 9 in Tunisia, 82 in Ethiopia, and 470 in Nigeria. There

is such an exotic abundance of languages on the busses in Naples these

days that you feel as if you have wandered into a workshop run by the

Summer Institute of Linguistics, those busy language beavers of bible

translation who tell us (at www.sil.org),

for example, that there are 8 languages spoken in Sri Lanka, 8 in the

Ukraine, 9 in Tunisia, 82 in Ethiopia, and 470 in Nigeria.

I hear

some of them, I'm sure, on the busses, depending on the time of day.

In the mornings there are loads of immigrant woman from Sri Lanka on

their way to work as maids and cooks (termed COLF in Italian, for "collaboratrici

familiari" -- family helpers). Many of them are from the Ukraine

and Sri Lanka. Later in the day, young African men toting huge sports

bags jammed with sundry leather goods such as purses and belts are seen

making their way to the bustling pedestrian malls downtown to peddle

their goods.

Interestingly,

of the 33 languages listed for Italy, I generally hear only two of those

on the busses: one is standard Italian; the other is Neapolitan dialect

(all 5,000,000 speakers of which live on my street and try to park their

cars in my space!). There is even a language I had never heard of,

much less actually heard:

| Judeo-Italian.

A tiny number speak it fluently; perhaps 4,000 occasionally use

elements of it in their speech (1/10th of Italy's 40,000 Jews).

Linguistic affiliation: Indo-European, Italic, Romance, Italo-Western,

Italo-Romance. More commonly spoken two generations ago. Used

in Passover song. Jewish. Nearly extinct. |

(The

Jewish synagogue in Naples is hidden off of a small courtyard near

Piazza dei Martiri [photo])

I

don't think anyone in the small (around 300-400) Naples Jewish community

speaks it, but I'll have to ask Aldo, a friend of ours. He is approaching

90 years of age and ten years ago became the second oldest university

graduate in the history of the Italian state. He was a young man when

the Fascists were in power and, because he was a Jew, was denied entrance

to a university. He bided his time and years later, at the age of 80,

wrote his university dissertation on The Influence of Napoleon on

the Liberation of European Jewry. He says he had difficulty even

finding a so-called "graduate advisor" for his thesis, that is, some

professor who knew enough about the subject to judge what he wrote.

They did a short spot on him on national television, where they showed

him getting his degree. He sported an elegant blue suit and an enormous

smile. I

don't think anyone in the small (around 300-400) Naples Jewish community

speaks it, but I'll have to ask Aldo, a friend of ours. He is approaching

90 years of age and ten years ago became the second oldest university

graduate in the history of the Italian state. He was a young man when

the Fascists were in power and, because he was a Jew, was denied entrance

to a university. He bided his time and years later, at the age of 80,

wrote his university dissertation on The Influence of Napoleon on

the Liberation of European Jewry. He says he had difficulty even

finding a so-called "graduate advisor" for his thesis, that is, some

professor who knew enough about the subject to judge what he wrote.

They did a short spot on him on national television, where they showed

him getting his degree. He sported an elegant blue suit and an enormous

smile.

Aldo speaks

only Italian, and it is my impression that almost no Italian Jews speak

Yiddish, for example. Once, an elderly Jewish gentleman from New York

whom I met in Naples asked if there was a synagogue in Naples. Indeed,

there was, and I took him down there. He spoke no Italian, but he did

speak Yiddish, a disappearing language even among American Jews. He

managed to communicate at the Naples synagogue in Yiddish with one old

gentleman, a resident of Naples but originally from Eastern Europe.

They spoke while the younger generation of Neapolitan Jewry stood around

and listened, absolutely transfixed as they listened to the historic

language of the Diaspora.

Bourbons

(8), royalty (1); Savoy (1)

Charles

and Camilla of Bourbon

I

think the heraldic mumbo-jumbo for a monarchy that is "out of work,"

so to speak, is that it is "in abeyance". The deposed Savoys of Italy,

for example -- for those who would like the Italian monarchy to return--

have been "in abeyance" since 1946 when Italy, by referendum, chose

a republican form of government. I

think the heraldic mumbo-jumbo for a monarchy that is "out of work,"

so to speak, is that it is "in abeyance". The deposed Savoys of Italy,

for example -- for those who would like the Italian monarchy to return--

have been "in abeyance" since 1946 when Italy, by referendum, chose

a republican form of government.

The Bourbons

of Naples are a different matter. They never ruled Italy, but, rather,

The Kingdom of Naples (also known as The Kingdom of The Two Sicilies)

until they were deposed by force in 1860 and said kingdom was incorporated

into another state --The Kingdom of Italy. Thus, you cannot say that

the Bourbons of Naples are "in abeyance" because there is no longer

a Kingdom of Naples. They are just plain out-of-work, left-over nobility

who travel around, being quaint.

Prince

Charles of Bourbon --who would be the King of Naples, today, if the

19th century had never happened-- was in Fondi (near Gaeta, north of

Naples) yesterday, being quaint. He presided over a ceremony that unveiled

the new uniforms of the Fondi traffic police, uniforms identical

to those made official by royal decree for the National Guard of the

Kingdom of Naples in 1848. "We are not trying to raise a Bourbon army,"

said Charles. "We just want people to be interested in their history."

The two policemen and one policewoman interviewed on TV with the prince

cut a dashing figure and seemed amusedly content in their new garb.

(The fact that 1848 was a year of widespread anti-monarchical turmoil

in Naples and elsewhere in Europe went uncommented upon.)

Monaciello;

spirits (good & evil) (1);

There

is a small lizard guarding our house; at least, I hope that is what

it is doing. I realize that there are other evolutionary scenarios that

call for the lizard to grow to the size of a komodo dragon and eat us,

but I'd rather not dwell on that possibility. There

is a small lizard guarding our house; at least, I hope that is what

it is doing. I realize that there are other evolutionary scenarios that

call for the lizard to grow to the size of a komodo dragon and eat us,

but I'd rather not dwell on that possibility.

My wife's

and my own current thinking is that the lizard represents a manifestation

of the "monaciello" ("little monk"), a kind of Neapolitan leprechaun,

a usually benevolent figure that protects you and, just maybe, might

show you where treasure is hidden. He is one of the many such mischievous

Pucks, imps and sprites that show up in various cultures around

the world. Monaciello --as the name would indicate-- normally looks

like an itsy-bitsy monk and is said to live in the wine cellar. We have

no wine cellar. I am puzzled by that theological contradiction, but

I have read that "monaciello" can also assume the shape of a cat or

a serpent; a lizard is a serpent, of sorts, so maybe, just maybe...

So far,

he (henceforth "he", since a "little monk", in whatever incarnation,

is, by definition, a male) simply scurries across the room, stops and

stares at us for a while, does that thing with his tongue, and

then goes away. My wife claims he is getting bigger. I, hopefully, suggest

that that comes from all the bugs he has been eating. (Indeed, our abode

is remarkably free of insects.) He has also replaced a previous,

smaller lizard we found in the dearly-departed, shrivelled-up state

some months ago. This is either (1) a good sign, in that there is, apparently,

an entire cadre of good spirits dedicated to our well-being, or (2)

ominous, in that maybe lizard number 2 killed lizard number 1 and is

now just biding his time (see "other evolutionary scenarios" in par.

1, above) waiting for the return of the Age of Reptiles.

Indeed,

my Neapolitan mother-in-law was convinced that ‘spirits’

(possibly a "monaciello" prankster) played tricks on her by moving things

around the house. Once they moved her house-keys and before that

they nabbed her sweater. I put quotes around ‘spirits’ because

that’s what she called them. I suggested ‘hobgoblins', ‘demons’,

or ‘howling hunks of ectoplasm’. One does not joke about

such things, however.

“I

put them right there, and now they’re gone, mister young punk

rationalist know-nothing unbeliever. How do you explain that?”

“Easy,

mother-in-law. You must have put them somewhere else.”

“Ha!

If I had put them somewhere else, then that’s where they would

be, right? But they’re not there, either! So where are they, if

you know so much? Besides, the things always turn up eventually, which

proves they were gone in the first place.”

Touché.

Now, I

know that the supernatural exists or does not exist quite independently

of whether or not I believe in it. Logical Positivists among you may

argue with that statement, but then you brainoids have never tangled

with lizards, so I suggest you get with the program.

Construction,

urbanology (1)

A

cabdriver complained to me the other day about all the construction

sites in the city. "I can't get people where they're going, and they

all think I'm trying to run up the fare on them by driving through the

Panama canal just to get them home. There are 50 open construction sites

in town!" A

cabdriver complained to me the other day about all the construction

sites in the city. "I can't get people where they're going, and they

all think I'm trying to run up the fare on them by driving through the

Panama canal just to get them home. There are 50 open construction sites

in town!"

The paper this morning more or less confirmed what he said as

well as what I can see from my own window. Near my house, there is a

street that has been torn up for five weeks and shows no signs of being

ready for traffic in the near future.

The paper

today ran a map showing the locations of 35 sites that traffic

simply has to avoid or try to go around somehow. They range from the

complicated and eternal construction for the new Naples metropolitana

-- the subway-- to simple ditches along the streets for fiber optic

lines and assorted plumbing --all of which, however, close the road.

"Eternal"

brings to mind the great Italian expression, "La fabbrica di San Pietro!"

used as a metaphor of things that take too long to build, referring

to the great length of time it took to finish St. Peter's cathedral

in Rome. You hear that figure of speech a lot these days.

Totò

(1898-1967) (1)

It is proverbial that there is something 'universal'

about humour, yet, nothing translates with more difficulty from one

culture to another than film comedy. Great exceptions, such as Chaplin

and Laurel & Hardy, though they may have wound up making talkies,

more or less depended on their genius for visual humour, and slapstick

developed in an age when humour was silent. Once films started to speak,

the rules changed, which is why highly verbal comics such as Groucho

Marx are so difficult to render into another language. A pie in the

face, a prat fall, or a piano falling downstairs cross cultural and

language barriers much easier than trying to translate, "Bernstein is

out in the corridor waxing wroth!" "Yeah? Well, tell him to get in here

and let Roth wax himself for a while!" It is proverbial that there is something 'universal'

about humour, yet, nothing translates with more difficulty from one

culture to another than film comedy. Great exceptions, such as Chaplin

and Laurel & Hardy, though they may have wound up making talkies,

more or less depended on their genius for visual humour, and slapstick

developed in an age when humour was silent. Once films started to speak,

the rules changed, which is why highly verbal comics such as Groucho

Marx are so difficult to render into another language. A pie in the

face, a prat fall, or a piano falling downstairs cross cultural and

language barriers much easier than trying to translate, "Bernstein is

out in the corridor waxing wroth!" "Yeah? Well, tell him to get in here

and let Roth wax himself for a while!"

The Neapolitan

comic Antonio De Curtis, known as Totò, is another example of

humour that can be appreciated across cultures. True, he is often full

of the verbal dexterity that only native speakers of Italian can appreciate,

yet his flights of outrageous language are so often combined with pure

visual humour that he is easily one of the most accessible of all film

comics, language and culture notwithstanding.

Nothing

will start a marathon session of tale-swapping quicker than Neapolitans

sitting around recalling scenes from their favorite Totò films.

If you want one where the pompous get their come-uppance, there's

the train scene where he offers to help a windbag senator with his luggage,

taking each piece and carefully passing it out the window of the moving

train, and for sheer pantomimic grace, only Chaplin at his best can

compare with Totò's version of a marionette puppet dancing his

way across the stage to the strains of the Parade of the Wooden Soldiers.

His

early career started after WW I in vaudeville and expanded into films.

He made 85 of them in all. Some of them, of course, are silly potboilers,

fun but forgettable. Others are "art," the kind you wind up admiring,

but still puzzling over and studying in History of Cinema classes, such

as his brilliant work in Uccellacci ed uccellini, produced by

another genius, Pier Paolo Pasolini. Others, the most memorable ones,

have him in the role of the true clown, the little man down on his luck,

just trying to make it through another day. There is this poignancy

in Guardie e Ladri (Cops and Robbers). Totò, as a thief,

spends much of the film making a good-natured overweight policeman

chase after him. They become friends and though Totò has to go

off to jail, the policeman winds up promising to send postcards to his

family from different places around Italy so they'll think Totò

is just off on a business trip. Then, there is some of Everyman's would-be

defiance of Authority in a film called Due Marascialli, when

a high-ranking Nazi officer in WW II Italy screams at Totò: "I

can do what I want. I have a blank check!" "A blank check?" answers

Totò, in a retort now proverbial in Italian, "Well, you can wipe

you a* * with it!" His

early career started after WW I in vaudeville and expanded into films.

He made 85 of them in all. Some of them, of course, are silly potboilers,

fun but forgettable. Others are "art," the kind you wind up admiring,

but still puzzling over and studying in History of Cinema classes, such

as his brilliant work in Uccellacci ed uccellini, produced by

another genius, Pier Paolo Pasolini. Others, the most memorable ones,

have him in the role of the true clown, the little man down on his luck,

just trying to make it through another day. There is this poignancy

in Guardie e Ladri (Cops and Robbers). Totò, as a thief,

spends much of the film making a good-natured overweight policeman

chase after him. They become friends and though Totò has to go

off to jail, the policeman winds up promising to send postcards to his

family from different places around Italy so they'll think Totò

is just off on a business trip. Then, there is some of Everyman's would-be

defiance of Authority in a film called Due Marascialli, when

a high-ranking Nazi officer in WW II Italy screams at Totò: "I

can do what I want. I have a blank check!" "A blank check?" answers

Totò, in a retort now proverbial in Italian, "Well, you can wipe

you a* * with it!"

A number

of other Totòisms have found their way into the language. "Siamo

uomini o caporali?!" ("Are we men or corporals?") and the immortal,

but untranslatable line (because it contains a grammatical error which

contradicts the spirit of the sentence): "Signore si nasce ed io

lo nacqui!" (Maybe something like, "Gentlemen are born, not made,

and I is one!") He was also the author of a number of well-loved poems

and songs in Neapolitan dialect, most memorable of which are A' livella

(a poem about death as the great equalizer) and "Malafemmina,"

a love song.

Like many

comics, Totò did not become appreciated as a "true clown" until

after his death. But most Italians knew right from the start what it

took critics decades to figure out, and now through the pleasant little

time-machine known as television, we can all see why.

Castellammare,

shipbuilding

| Jakob

Hackert's painting of the launching of a ship at Castellammare in

the late 18th century. |

The

Castellammare shipyard near Naples seems to be bustling and in fine shape.

The 56,000 ton Grande Francia has been finished and will be christened

and launched shortly. It is one of the so-called "Car Trak Carrier" fleet

of the Grimaldi Group of Naples and is the first of five such ships to

be built. They will all have the capacity to transport 2500 cars, 850

containers and have a "linear capacity" of 2500 meters for additional

heavy vehicles. Another of the five, Grande Amburgo, will be built

in Castellammare starting in the new year. Yards in Palermo and Ancona

will take over the construction of the other three. A new cruise ship,

the Ferryn Athara, for the Tirrenia lines, will also start construction

in Castellammare in 2003. The

Castellammare shipyard near Naples seems to be bustling and in fine shape.

The 56,000 ton Grande Francia has been finished and will be christened

and launched shortly. It is one of the so-called "Car Trak Carrier" fleet

of the Grimaldi Group of Naples and is the first of five such ships to

be built. They will all have the capacity to transport 2500 cars, 850

containers and have a "linear capacity" of 2500 meters for additional

heavy vehicles. Another of the five, Grande Amburgo, will be built

in Castellammare starting in the new year. Yards in Palermo and Ancona

will take over the construction of the other three. A new cruise ship,

the Ferryn Athara, for the Tirrenia lines, will also start construction

in Castellammare in 2003.

Castellammare

has a long history as a shipyard. Neapolitans learned shipbuilding from

the Phonecians and the Greeks, then became the principal shipwrights

for the Romans, contributing to the Empire's domination of the Mediterranean.

Neapolitan shipwrights continued their activity even during the Middle

Ages, thanks to extensive merchant and cultural trading between Europe

and the Middle East. The Normans, Swabians,

Angevins and Aragonese carried on maritime

commerce, and Naples was of primary importance in the southern Tyrrhenian

sea. In 1571, Neapolitan yards contributed greatly to the successful

outcome of the Battle of Lepanto by furnishing a number of ships in

the victorious fleet.

In 1734

with the ascension of the Bourbons to

the throne, Neapolitan shipwrights began building naval ships for the

protection of the newly independent kingdom. In 1739 the first

completely Bourbon frigate was launched, the S. Carlo e Partenope.

In the same year in Naples, the Accademia di Marina was opened;

it was the first academy in Italy for the training of naval officers.

In 1780 Ferdinand IV established a Ministry of the Royal Navy and opened

a shipyard at Castellammare di Stabia to build ships for the kingdom's

fleets. Ferdinand chose Castellammare as the site of the royal shipyards

because of the inhabitants' reputation as master craftsmen. The kingdom,

itself, was unstable at times, but the Bourbons, nevertheless, developed

the facility at Castellammare into one of the most impressive in the

Mediterranean.

In 1818

at Vigliena, the first steamship in Italy was launched, the Ferdinand

I. By the time of Italian unification, the yards at Castellammare

had built fifty ships of medium tonnage for the navy, as well as countless

smaller merchant vessels. On January 18, 1859, Francesco II witnessed

the launching of what turned out to be the last ship built for the navy

of Naples, the frigate Borbone.

| Mt.

Vesuvius seen from the port of Castellammare. |

The

last years of the kingdom of Naples saw a general restructuring of port

facilities. In addition to the shipyards, the Kingdom of Naples had

other considerable industrial and manufacturing activity, particularly

in metallurgy, an industry which drew widebased financial support from

English, French and Swiss entrepreneurs. The

last years of the kingdom of Naples saw a general restructuring of port

facilities. In addition to the shipyards, the Kingdom of Naples had

other considerable industrial and manufacturing activity, particularly

in metallurgy, an industry which drew widebased financial support from

English, French and Swiss entrepreneurs.

With the

unification of Italy came a reevaluation of the shipyards of the ex-Kingdom

of Naples. The question of Castellammare was, of course, but one part

of the much larger question of just how much industry should be assigned

to the southern half of a unified nation.

Since unification,

Castellammare has had to contend with numerous proposals to close the

shipyards altogether. Also, it has had to battle competition from other

shipyards throughout Italy. Nevertheless, between 1861 and 1918

the yards launched 83 naval vessels, many of which proved to be among

the finest in the nation's fleets. From 1918 to the early 1980s, 170

more ships were built at Castellammare, some of more than 50,000 tons

capacity. Two ships, well-known to all, have come from the Castellammare

yards: the naval training ship, Amerigo Vespucci (1931) and the

bathyscaph Triest (1953) which took Auguste Piccard down to 3,150

metres in the waters off Ponza.

|