©

2004 Jeff Matthews & napoli.com

Dubbing

(film)

This

model of Oliver Hardy is on via S. Gregorio Armeno. The Italian

voice of Ollie was Alberto Sordi. It was a spectacularly successful

example of dubbing.

|

I

was watching a skit with Neapolitan comic Massimo Troisi the other night

on TV. Although I should know better, I was upset that I didn't understand

the uncompromisingly authentic Neapolitan dialect. There were, however,

subtitles to make the dialect intelligible to viewers from elsewhere in

Italy who might be watching. For a long time, I had assumed that foreigners

were the only ones who had such troubles. Not so. Italian dialects can

vary considerably from standard Italian, so it is common to see such films

with subtitles. I

was watching a skit with Neapolitan comic Massimo Troisi the other night

on TV. Although I should know better, I was upset that I didn't understand

the uncompromisingly authentic Neapolitan dialect. There were, however,

subtitles to make the dialect intelligible to viewers from elsewhere in

Italy who might be watching. For a long time, I had assumed that foreigners

were the only ones who had such troubles. Not so. Italian dialects can

vary considerably from standard Italian, so it is common to see such films

with subtitles.

Interestingly,

that is about the only time in Italy that you see subtitles in films.

Foreign films—unlike Italian dialect films—are always dubbed

into Italian. Films are dubbed so well and so consistently in Italy,

that it is common for a single dubber to shadow the career of a foreign

actor for years. For example, with your back turned to the screen, even

if the film is in Italian, you know that Woody Allen is speaking, because

his dubber is always Italian comic Oreste Lionello. If Marlon Brando,

Robert Redford and Paul Newman all sound the same in Italian, it's because

the same dubber, Giuseppe Rinaldi, does all three of the voices.

Emilio Cigoli does both John Wayne and Clark Gable, so you may actually

have to turn around and look at the screen to find out if you're watching

Stagecoach or Gone With the Wind.

Dubbing

a film is much more expensive than simply slapping subtitles at the

bottom of the screen. Dubbing involves a sound studio, hiring voices

for each character and doing take after take in an attempt to get the

original inflecions into a voice, and then making sure that the new

language synchronizes as well as possible with the lip movements on

the screen. Nothing is worse than bad dubbing, where the emotions of

the voice don't fit the action, and where the synchronization is so

out of whack that half the time the actors look like poor souls on street

corners making silent fish-like mouth movements to themselves.

The biggest

reason why Italians choose to dub films rather than subtitle them goes

back to when "talkies" started in the late 1920s. In a nation dealing

with drastic differences in dialects, dubbing was a way to help create

a sense of a single national language. Thus, even Italian actors with

easily identifiable regional accents have been dubbed into more "standard"

Italian. (At the beginning of her career, Sophia Loren was dubbed, apparently

because of her regional accent from Pozzuoli, near Naples.) Interestingly,

after two decades of good dubbing, Italians were so used to standard

Italian in films, that when the wave of post-WW II Italian films known

as "Neo-Realism" came in, with their dialogues recorded live in Sicilian,

Neapolitan and Roman dialects, it came as a shock to many Italians to

realize that they didn't really understand many of their own countrymen.

("Precisely the point," said more than one Neo-Realist director.)

Italian

dubbing is generally so consistent that mimics regularly "do" foreign

actors who have characteristic vocal styles—say, John Wayne or

Jimmy Stewart. Such attention is paid to quality dubbing that Greta

Garbo, for example, upon hearing herself in Italian for the first time,

sat down and wrote a fan letter to her Italian voice, owned by actress

Tina Latenzi. And some dubbing, of course, requires the same unusual

verbal dexterity as the original voice—witness the tongue-twisting

pyrotechnics of Stefano Sibaldi, the Italian voice of Danny Kaye.

Perhaps

the strangest sidelight in this whole matter is that dubbed voices can

become part and parcel of another culture, evoking allusions and inside

jokes just as do the original voices in their own culture. The Italian

voices of Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy are the best example of this.

When talkies came in, Laurel and Hardy had already achieved world-wide

fame on the basis of their short silent movies. There was such a new

demand for them speaking, however, that for a time they actually reshot

their scenes hurriedly in other languages, pronouncing their lines

from scripts written in phonetic English. These scenes would then

be sent abroad to be spliced into the rest of the film, which had been

remade in the target language using local actors. That soon proved impractical,

especially for longer feature films. Consequently, for the Italian market

the decision was made to dub the films of Laurel and Hardy in American

studios using Italian-American actors, who, presumably, thought they

were speaking standard Italian. Their own Italian, however, had been

maimed by at least one generation of nasal semi-vowels, unrolled r's

and Wrigley's Spearmint.

When the

studios in Rome reviewed the first dubbed-in-America Laurel and Hardy

film to see what they had, the American English accented voices were

so hilarious, that someone came up with the idea of redubbing

everyone else into normal Italian, but leaving Stan and Ollie with accents.

There followed a nation-wide contest to find the voices of Laurel and

Hardy in Italian. One winner was the now famous Italian comic, Alberto

Sordi, whose career started as the voice of Oliver Hardy. His anglicized

Italian as 'Ollie' has become so much a part of Italian popular culture

that an Italian, today, can do Oliver Hardy by saying, with a broad

English language accent, "stupido " (accenting the second, instead of

the first, syllable, in imitation of Sordi's version of Oliver Hardy)

and have it recognized as instantly as an English-speaker would recognize,

"Well, here's another fine mess you've gotten me into!" Indeed,

Italian mimics still regularly pay tribute to Laurel and Hardy, imitating

the dubbed voices. (The Italian voice of Stan Laurel was Mauro Zambuto,

who, after WW II, moved to the United States and became a professor

of Electrical Engineering at the New Jersey Institute of Technology.)

So, without

taking anything away from the universal nature of the humor of Laurel

and Hardy, it is fair to say that in Italy, much of their popularity

was—and still is—due to the spectacularly successful way

they are dubbed. There is no Italian comic (not even the great Totò)

who, by voice alone, is as recognizable as are Laurel and Hardy in Italian.

The only competition in recognizability might be the Italian voice of

Donald Duck! Most of the voices in those cartoons are, indeed, dubbed

into relatively normal Italian—except for Donald. He still quacks,

but his Italian dubber is none other than Clarence Nash, the original

English voice of Donald Duck for the Disney studios and who dubbed himself

into many foreign languages—including Japanese. Apparently, Nash

was one of the few persons to have truly mastered the difficult trick

of compressing air in the cheek cavity and producing articulate quacks.

(Phoneticians call this the "buccal voice". To the rest of us, it's

known as "duckspeak".)

Anyway,

gotta run. I hear the sultry, breathless tones of Rosetta Calavetta

on the tube. Marilyn Monroe, to you.

Diplomatic

Relations, US/Naples (1); Hammett, A.

Quite

by accident I came across an item the other day from December, 1996.

It was a press statement from the U.S. State Department commenting on

the anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between

the USA and the Kingdom of Two Sicilies. In part, it said: Quite

by accident I came across an item the other day from December, 1996.

It was a press statement from the U.S. State Department commenting on

the anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between

the USA and the Kingdom of Two Sicilies. In part, it said:

| This

Day in Diplomacy: Establishment of Diplomatic Relations

With the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies on December 16, 1796.

Today

the city of Naples will commemorate the 200th anniversary of

the establishment of diplomatic relations between the United

States and the Bourbon Kingdom of the Two Sicilies of which

Naples was capital. The rapid expansion of American trade in

the Mediterranean basin and a growing regional instability created

by the French revolution and North African piracy required an

expanded diplomatic and military presence in the region by the

fledgling American government. Naples, as the largest

city on the Italian peninsula, was a major port of call for

American merchant vessels. Moreover, the Bourbon regime

still enjoyed in the last years of the 18th century its reputation

as one of the pioneering reform states of the European Enlightenment.

Until

most of Italy was united in 1861 as the Kingdom of Italy, the

United States maintained separate diplomatic and consular representatives

at Naples. Continuous U.S. diplomatic representation at the

court of the Two Sicilies only began in 1831, and then, in keeping

with the cautious regard of American republicanism toward European

monarchies, such representation was almost always a Charge d'Affaires

rather than a full Minister. American commerce, however,

made necessary continuous consular representation at Naples

from 1796. For 52 years, from 1809 until 1861, Alexander Hammett

of Maryland served continuously as American consul at Naples.

During his long tenure, Hammett reported on wars, revolutions,

and the expansion of U.S. trade.

|

I was in

Naples in December 1996, and I'm sure I would recall any large-scale

popular celebrations of the anniversary of the establishment of relations

between the USA and the Kingdom of Two Sicilies (also known as the Kingdom

of Naples). There were none—not even any clandestine humming of

the Bourbon Royal March. No doubt, this has to do with the fact that

said kingdom went out of business in 1860.

Alexander

Hammett sounds like an interesting person, though. He represented the

US in Naples for over half a century. The dates invite further investigation

that I shall have to get around to sooner or later. If he started his

tenure in 1809, that would be in the middle of the short reign of Murat, who ruled for Bonaparte during what is still

called the "The Decade" in Neapolitan history. When Murat was

deposed in 1814, it seems that Hammett simply stayed on as US representative.

That strikes me as unusual.

The first

mention of relations between the new American nation and Naples is in

the National Archives in Naples. A Neapolitan businessman, one Vincenzo

Cutini, made a request on March 12, 1783, to be appointed Consul in

the United States. That date is interesting in that it is before the

Treaty of Versailles officially ended the American Revolution, meaning

there really was no United States of America, yet. The King of

Naples, however, decided that the time was not yet ripe and Cutini's

request was turned down. Over the next two years, Thomas Jefferson,

John Adams and Benjamin Franklin all actively pursued the cause of Neapolitan

recognition of the US. Though diplomatic recognition did not result

from any of this manoeuvring, a somewhat informal period of commerce

ensued. Also, in 1785 the US, concerned about danger to its merchant

fleet in the Mediterranean at the hands of the Barbary pirates, requested

aid, if the need should arise, from the Neapolitan fleet.

By 1796,

the position of the United States had consolidated and it was in that

year that John Mathieu became the first American Consul in Naples. He

was followed in 1806 (the year that Murat took over Naples) by Frederick

Degan, who served until 1809, at which time Alexander Hammett became

Consul and then Charge d'Affaires when full diplomatic relations were

established in 1834. In November 1860, the US diplomatic legation was

closed as the kingdom of Naples was officially annexed to the rest of

Italy. Consular representation in Naples continued, but Hammett was

dischared by the new Lincoln administration. One source I have read

refers to him as "a gifted amateur" and another tells me that he died

in the "almshouse". That would be a sad end. If he left a diary, I wonder

if it is in the National Library downtown. As much as I hate to fight

my way into that place, this one is tempting.

Posillipo

(2); Seiano Grotto (2); Vedius Pollio (villa)

I finally got the opportunity to take a tour through the Seiano Grotto). We started at the Coroglio (Bagnoli)

side and traversed the 700-meter tunnel to come out on the Posillipo

side and then walked up and looked at the Imperial Villa of Pausylipon. I finally got the opportunity to take a tour through the Seiano Grotto). We started at the Coroglio (Bagnoli)

side and traversed the 700-meter tunnel to come out on the Posillipo

side and then walked up and looked at the Imperial Villa of Pausylipon.

The information

in the other entry (linked above) is essentially correct, but needs

some amplification. The name "Seiano" may be a misnomer for this impressive

bit of engineering. The tradition that links the construction of the

tunnel to the will of Lucius Aelius Sejanus, Tiberius' ambitious right-hand

man and would-be successor, is probably wrong. More recent archaeological

thought on the matter connects the gallery to Vedius Pollio, the builder

of the spectacular villa, itself. The tunnel was a private passage for

Pollio so he wouldn't have to take the long way home.

Pollio

was an ex-slave from Benevento known for his industriousness, ambition,

economic wheelings and dealings in North Africa and subsequent great

wealth, and cruelty to his own servants. His villa is mentioned in a

number of classical references as a worthy rival in luxuriousness to

even the fabled villa of Lucullus, a few miles down the coast in what

was Neapolis, itself. It was only after Pollio's death that the premises

passed to Caesar Augustus, apparently in exchange for a promise by the

emperor to honor Pollio's name with a public building in Benevento—a

promise that Augustus reneged on. (Who knows why? Maybe Augustus just

didn't like Pollio. There is one story that says that Pollio was about

to put to death a servant who had just broken a dish. Houseguest Caesar

Augustus was so appalled that he bought the servant and his entire family

from Pollio and took them with him back to Rome—after ordering

that the rest of Pollio's crockery be smashed. (Name a building after

you? I don't think so.)

When Augustus

came into possession of the property, the tunnel then became part of

the public network of roads that connected the important port of Pozzuoli

to Naples, much like its sister tunnel

that joined Fuorigrotta to Naples (near what is today the Mergellina

train station), and only then that the premises became an "imperial"

villa. There are signs that the estate was still an imperial residence

under Hadrian (the early 2nd century) and that the tunnel itself was

in use as late as the fall of the empire, itself—the late 6th

century. After that, it disappears from history until 1840 when the

Bourbons rediscovered the Coroglio entrance to the gallery while doing

some road building of their own. The tunnel was sealed in the 1980s

and then reopened in the 1990s for the restoration that finished just

two years ago.

The imperial

premises start a hundred yards or so from the exit of the tunnel up

a slope toward the cliff, itself. They consisted of a residence, temple,

amphitheater (capacity about 2,000), an odeon (a covered theater), and

a nympheum (a shrine), all spread over a considerable area directly

beneath the height of Cape Posillipo. One view is to that cape and the

bay of Pozzuoli beyond, including the small island of Nisida and the

larger island of Ischia miles away. The western panorama is toward Naples,

Vesuvius, and Capri. "Breathtaking" doesn't begin to cover it.

What one

sees today (photo at top), however, in the way of remnants of imperial

splendor is shabby, indeed— and this is not just due to the ravages

of time. The residence was rediscovered at about the same time as the

tunnel, and, almost immediately, someone built a large private villa

directly above the main amphitheater, using much of the original masonry

for construction material. That villa is now abandoned and totally in

ruins, and the adjacent amphitheater shows the ravages of that original

depredation plus another century and a half of looting. Almost none

of the looted marble and statuary has wound up in proper museums.

It is not

clear whether this Roman estate was built on the site of earlier Greek

structures or not. One interesting item that says "maybe" is the fact

that the rows of seats in the amphitheater are hewn out of the stone

itself—in the manner of Greek amphitheaters—rather than

being freestanding. All of that remains to be determined as restoration

goes forward. The property, itself, is now partially in private hands,

but restoration continues on that part of the property that has reverted

to the cultural offices of the state. The plans are ambitious. So far,

the amphitheater has been cleared of rubble and the small odeon has

been restored such that a small public can enjoy performances of one

sort or another during the summer months overlooking the coast of Posillipo.

Piedigrotta

In a culture that abounds with famous place names such as "Santa

Lucia" and "Vesuvius," "Piedigrotta" still stands out as

one of the best-known names among Neapolitans, themselves. The name,

itself, means "at the foot of the grotto," referring to the nearby Roman tunnel that leads beneath the hill

in back of the church of Santa Maria di Piedigrotta; that grotto connects

the section of Naples known as Mergellina at the west end of the

bay with Fuorigrotta —"beyond the grotto," today a thriving and

large suburb of Naples. The old Roman tunnel was bypassed many decades

ago by a modern traffic tunnel on the right of the church. In a culture that abounds with famous place names such as "Santa

Lucia" and "Vesuvius," "Piedigrotta" still stands out as

one of the best-known names among Neapolitans, themselves. The name,

itself, means "at the foot of the grotto," referring to the nearby Roman tunnel that leads beneath the hill

in back of the church of Santa Maria di Piedigrotta; that grotto connects

the section of Naples known as Mergellina at the west end of the

bay with Fuorigrotta —"beyond the grotto," today a thriving and

large suburb of Naples. The old Roman tunnel was bypassed many decades

ago by a modern traffic tunnel on the right of the church.

[See

here and here for more about

tunnels.]

Newspaper

from 1885 featuring the Festival of Piedigrotta

Piedigrotta

is connected in popular Neapolitan culture with the famous "Festival

of Piedigrotta", a celebration on September 8, a spectacular parade

led by viceroys and Kings, passing along the entire length of

the seaside road, Riviera di Chaia, and winding up at the church, itself.

The parade was a yearly affair in the 1600s under the Spanish (who built

the road leading to the church as they expanded the city to the west)

and in the 1700s under the Bourbons. It was still held during the 19th

century. Piedigrotta

is connected in popular Neapolitan culture with the famous "Festival

of Piedigrotta", a celebration on September 8, a spectacular parade

led by viceroys and Kings, passing along the entire length of

the seaside road, Riviera di Chaia, and winding up at the church, itself.

The parade was a yearly affair in the 1600s under the Spanish (who built

the road leading to the church as they expanded the city to the west)

and in the 1700s under the Bourbons. It was still held during the 19th

century.

Beginning

in the 1830s, the Festival of Piedigrotta held a song-writing contest

for composers of Neapolitan songs and

is responsible for providing us with such songs as "Funicuì-Funiculà" (the winner from

1880) and many others. Much more recently, although there is still a

celebration at the church, the parade is no longer held.

The church

of Santa Maria di Piedigrotta is first mentioned in a document from

1207 and is mentioned prominently by both Boccaccio and Petrach in the

1300s. Over the centuries, the church has been redone and expanded many

times. The current façade of the church is from the 1850s. There

is also an adjacent monastery that now serves as a military hospital.

Also, near the entrance to the grotto (above) and behind the church

is a monument billed as Virgil's Tomb.

Perhaps

the most interesting thing, historically, has to do with the site, rather

than the church. That is, the grotto led to the fabled Phlegrean Fields, the mythological entrance to Hades,

and thus lent itself well to mysterious carryings-on. Pre-Christian

religions almost certainly used the site near the present church as

a place for their rituals. One speculation—by no less than the

great Neapolitan dialect poet, Salvatore Di Giacomo (citing "scholarly sources")—is

that here was the setting of Petronius' Satyricon, that great

bit of pornography from the first century a.d. Di Giacomo starts to

cite the passage about the three young men out for a good time going

into the cave and running into a band of women. Then, he blushes to

continue. As do I.

Caracciolo,

F.

Portrait

of Caracciolo by an unknown artist

"Caracciolo"

is an old and prominent Neapolitan surname. There are at least 50 bearers

of that name in the current Naples phone book. Indeed, the name has divided

into various branches over the centuries—"Caracciolo–of–here"

and "Caracciolo–of–there," resulting in some very impressive

listings in the directory. There is a "Prince Landolfo Amrogio Caracciolo

di Melissano". That is the longest one I see, although, without a title,

Francesco Alberto Caracciolo di Torchiarolo" edges him out by a few letters.

(From the address in the phone book, he is my next-door neighbor, although

I don't know why that should matter to me.) "Caracciolo"

is an old and prominent Neapolitan surname. There are at least 50 bearers

of that name in the current Naples phone book. Indeed, the name has divided

into various branches over the centuries—"Caracciolo–of–here"

and "Caracciolo–of–there," resulting in some very impressive

listings in the directory. There is a "Prince Landolfo Amrogio Caracciolo

di Melissano". That is the longest one I see, although, without a title,

Francesco Alberto Caracciolo di Torchiarolo" edges him out by a few letters.

(From the address in the phone book, he is my next-door neighbor, although

I don't know why that should matter to me.)

There are

even four different streets named via Caracciolo in Naples: Batistella

Caracciolo (renowned painter of the Neapolitan Baroque, contemporary

of Ribera and Caravaggio); Bartolomeo Caracciolo, about whom I know

nothing; T. Caracciolo (the T stands for Tristan, I think); and the

one that all Neapolitans think of when they hear the name "Caracciolo"

—Francesco. The splendid road that runs from Mergellina to Piazza

Vittoria along the sea, fronting the Villa Comunale, thus, is named

for Francesco Caracciolo (1752-1799), the Neapolitan admiral whose named

is dramatically linked in history with the rise and fall of the Neapolitan

Republic of 1799 and with the principal players in that episode: Queen

Caroline, King Ferdinand, Lady Hamilton, and, especially, Horatio Nelson.

(What follows may be read as an adjunct to other entries about that

period: The Bourbons, part 1; Eleonora

Fonseca Pimentel; and Cardinal Ruffo.)

Francesco

Caracciolo was born January 18, 1752 of a noble Neapolitan family. He

entered the navy at a young age and fought with distinction with the

Kingdom of Naples' ally, the British, in the American Revolutionary

War. He also fought the Barbary pirates and against the French at Toulon.

In December of 1798, the Neapolitan monarchy fled the capital in the

face of the insurgent Neapolitan republican forces backed by the French

army at the gates of the city. The King and Queen fled to Sicily on

Nelson's ship, the "Vanguard", escorted by Caracciolo on the Neapolitan

frigate "Sannita".

Caracciolo

returned to Naples in January to take care of private matters and arrived

in the city after the Republic had been declared. His behavior at that

point has remained the subject of speculation. Either he resented being

snubbed by King Ferdinand, who had fled aboard Nelson's vessel and not

Caracciolo's, or he was appalled at the cowardly flight, itself, or

he was truly taken with the newly proclaimed Neapolitan Republic. Whatever

the case, he took command of the naval forces of the new Republic. In

other words, he betrayed his king.

The

church of Santa Maria della Catena, the final resting place of Admiral

Caracciolo.

He led the Republican

navy against royalist Neapolitan and British naval forces for the brief

life of the Republic, his last major engagement being an attack on the

British flagship, the Minerva, inflicting damage on that vessel.

The Republic, however, was doomed by the withdrawal of French forces

from Naples and by the arrival of the royalist Army of the Holy Faith

under Cardinal Ruffo. Caracciolo was captured. His trial is a matter

of record and takes place against the whole backdrop of deceit by which

the Royalist forces actually retook the city. The agreed to an armistice,

promised safe passage to Republican defenders (presumably including

Caracciolo), and then put the Republicans on trial, anyway. He led the Republican

navy against royalist Neapolitan and British naval forces for the brief

life of the Republic, his last major engagement being an attack on the

British flagship, the Minerva, inflicting damage on that vessel.

The Republic, however, was doomed by the withdrawal of French forces

from Naples and by the arrival of the royalist Army of the Holy Faith

under Cardinal Ruffo. Caracciolo was captured. His trial is a matter

of record and takes place against the whole backdrop of deceit by which

the Royalist forces actually retook the city. The agreed to an armistice,

promised safe passage to Republican defenders (presumably including

Caracciolo), and then put the Republicans on trial, anyway.

There was

never any doubt as to Caracciolo's fate. Queen Caroline had relayed

to Nelson her wish that Caracciolo should hang, no matter what. Caracciolo

was tried aboard a British ship, the Foudroyant, by Neapolitan

royalist officers and charged with high treason. He was not permitted

to call witnesses in his defence. He was condemned to death by three

votes to two. He was not given the customary twenty-four hours for personal

matters of the spirit. His request to be shot was denied and he was

hanged from the yardarm of the Minerva on the morning of June

30, 1799. His body was weighted and thrown into the sea.

One of

the mainstays of modern Neapolitan mythology is that the body refused

to sink, floating to the surface and eerily bobbing its way towards

shore. Indeed, there is even a painting showing King Ferdinand aboard

his ship, aghast at the sight of the admiral's corpse floating alongside.

Whatever the case, Caracciolo's body was retrieved from the sea and

his remains now rest in the small church of Santa Maria della Catena

in the Santa Lucia section of Naples.

Cucceius

Auctus, Lucius

There

was an interesting documentary on television last night about the underwater

remains of Portus Iulius, the port for the Roman Western Fleet. The

coastline and sea-level have changed in two-thousand years and much

of the original port is now underwater in the bay of Pozzuoli. I have

been scuba diving in that area and recall some of the submerged bits

and pieces of what was once the most important port for the greatest

fleet in the world. Then, I head a name: "Lucio Cocceio," the architect,

the builder. I had heard that name before. There

was an interesting documentary on television last night about the underwater

remains of Portus Iulius, the port for the Roman Western Fleet. The

coastline and sea-level have changed in two-thousand years and much

of the original port is now underwater in the bay of Pozzuoli. I have

been scuba diving in that area and recall some of the submerged bits

and pieces of what was once the most important port for the greatest

fleet in the world. Then, I head a name: "Lucio Cocceio," the architect,

the builder. I had heard that name before.

Indeed,

Lucius Cucceius Auctus was apparently the architect, designer,

and builder under Caesar Augustus. By his accomplishments, he is hardly

to be matched in history. He built the original Pantheon in Rome in

27 b.c. He built four major tunnels in the area of Naples: the so-called

"Neapolitan Crypt," the tunnel that connected the port of Pozzuoli and

the adjacent area of the Phlegrean Fields with the city of Neapolis;

the "Gallery of Peace," which joined Lake Averno to fleet facilities

at Cuma; a tunnel that joined Lake Averno to nearby Lake Lucrino; and

the ("Seiano Grotta")—all this in addition to the

entire Portus Iulius, itself. Also, I

was wandering around the recently excavated old city of Pozzuoli. The

cathedral of Pozzuoli burned in 1964 and, lo and behold, they found

that it had been built over the "Temple of Augustus" (photo). The temple

was built at the behest of a rich merchant, one Lucius Calpurnius, during

the age of the August One—and built by Lucius Cucceius Auctus.

I am sure

that there were other prominent feats of engineering and construction

performed by Cucceius, except I don't know what they are. I was sort

of hoping to find an exhaustive—or even an exhausted—biography.

So far, no luck.

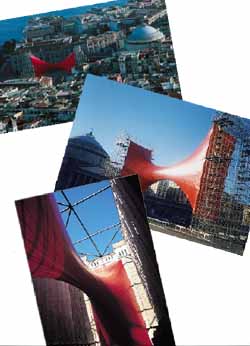

Art,

modern; Kapoor, Anish

The

city of Naples—in its never-ending quest to bring art to the masses

and especially to the masses who ride the subway to work—is not

just going to spruce up the soon-to-be-finished university station at

Monte Sant'Angelo with a few paintings or statues or even bronzed old

jalopies disguised as installation art. They have hired British/Indian

artist Anish Kapoor to turn the entire station, itself, into a work

of art. The station will be among the deepest in Italy (about 40 meters)

and—well, the area is in the Phlegrean Fields, not far from the

mythological descent into Hades— so, says Kapoor: "We want to

create the impression of a Dantean descent into the underworld." No

one seems to know exactly what that means, and few are in a hurry to

find out. It's hell getting to work, anyway. The

city of Naples—in its never-ending quest to bring art to the masses

and especially to the masses who ride the subway to work—is not

just going to spruce up the soon-to-be-finished university station at

Monte Sant'Angelo with a few paintings or statues or even bronzed old

jalopies disguised as installation art. They have hired British/Indian

artist Anish Kapoor to turn the entire station, itself, into a work

of art. The station will be among the deepest in Italy (about 40 meters)

and—well, the area is in the Phlegrean Fields, not far from the

mythological descent into Hades— so, says Kapoor: "We want to

create the impression of a Dantean descent into the underworld." No

one seems to know exactly what that means, and few are in a hurry to

find out. It's hell getting to work, anyway.

Neapolitans

are most familiar with Kapoor from his gigantic site sculpture, Taratantara,

originally created for the new Gateshead's Baltic Centre for Contemporary

Arts in England in 1999, but then set up in Piazza Plebiscito (photo)

in Naples in December of 2000 as that year's contribution to the annual

exposition of installation art of one sort or another (see

here). The title is meant to be echoic of the sound made by a trumpet

fanfare, as in Roman poet Quintus Ennius' line, "At tuba terribili

sonitu taratantara dixit" — ("But the trumpet sounded with

its terrible taratantara", the onomatopoeia usually left untranslated).

Indeed, the sculpture suggests two funnel-like trumpet bells joined

and flaring out to both ends, something like those strange geometric

figures that scientists use to describe what sort of transdimensional

hyperspace thing (a technical term) we shall have to traverse if we

ever hope to reach the stars. Taratantara was made of a shiny

red membrane, glittered in the sun, was about 50 meters long, 20 high

and anchored in Piazza Plebiscito by steel columns at each end. While

it was up, the columns were scaled by demonstrators. They weren't out

to damage the sculpture—and didn't—but the offices of the

Naples Prefecture bounds the north side of the square and that's always

a good place to have a demonstration.

I am reminded

of a clipping I read once in the paper:

| An

English art student's work was thrown out, literally, after an

official at a Birmingham art center mistook it for trash from

the opening day party. Ceri Davie's "Piece de Resistance"

involved red jellies displayed on plates and was intended as a

metaphor of decay. ‘Months of hard work had just gone to

waste,’ the artist said. "I was quite horrified. |

Very few

of us realize the tough row that artists have to hoe in dealing with

Philistines such as that art center official. This is probably because

practical hoes weren’t even invented until the Middle Ages. As

far as we know, the Philistines just got down on all fours and grubbed

their rows into shape with their hands.

Many years

before the Decadent Red Jelly affair referred to above, one of the artist’s

earlier works, Empty Paper Picnic Plate—which consisted

of an empty paper picnic plate— was not all well received by critics,

who found the title too hard to say five times real fast and who also

mistook "empty paper" as a metaphor of life instead of a Minimalist

description of paper picnics, the plate itself being just a secondary,

but sardonic, appliquè —which is just as well, since

it too was given the old heave-ho. Fortunately (maybe), it was saved,

since the art center official who tossed it, threw it into what he thought

was a trash bin, but which, in fact, was also past of the art show.

And then

there was the artist’s Hamburger, those little pointillist

nibbles of semi-conceptualist cholesterol-laden ground Bœuf,

a yummy but still youthful version of her later, futuristic, Quarter-Pounder

With Cheese, in which patrons of the art show were required to flip

burgers in the kitchen, then ask themselves in the drive-through microphone

if they “would like fries with that?” and then—ah,

the stochastic power of it all!—eat or not eat the work of art!

How was the artist to know that they had scheduled the exhibit in the

same hall as a dog show? It was to her credit as a resourceful master

of Performance Art that she retitled the whole thing, Gone to the

Dogs, A Metaphor. (Or Maybe It’s a Simile).

Davies

is not the only artist who has had this trouble. Fortunately, I am in

the possession of a section of the diary of Michelangelo (the National

Library knows nothing about this):

| January

8, 1504. Dear diary. I’m ruined. After years of work in

chipping away the pieces, I have finally figured out where

beauty is, and it’s not in chubby women with smiling faces.

I busted my hump on this one, too! (Alas, even in a society where

males with humps are considered good omens, there is not much

use for a sculptor with a busted one, I’m afraid.)

I

spent three years on this! A veritable mountain of chips, shards,

bits, detritus, little stone chunks lying where they fell, all

at different odd angles, each one with a special metaphor to

it, deconstructing, as it were, the sordid and complex

confusion of our times. And in stone! —in Carrara marble

as eternal as the plots, counter-plots and intrigues that surround

us. I was going to call it something like Plots, Counter-Plots

and Intrigues. (Ok, I hadn’t given it that much thought,

yet.) I figured it was about time someone put it all into permanent

artistic form. Why paint anymore?! The colors will just fade

and then someone will come along and invent cartoonists and

hire one of them to touch up my Sistine Chapel with paint-by-the-numbers

Day-Glo!

So

I finish it and leave it outside. Where else am I going

to keep it, in my living room? This morning it’s gone.

Those morons took the waste rock and put it on display! ‘It

looks just like a boy with a slingshot. Cool!’ they said.

And my work of art? ‘Oh, that crap? We threw it away,’

they said.

I

was talking about this with Leonardo From Vinci (man, what a

one-horse burg that dump is!). He has strung an invention of

his, a ‘talk gizmo’ between his house and mine —two

ceramic cups and a very long thread. It works all right, except

that since our houses are many miles apart, communication kind

of breaks down when Tuscan peasant women somewhere in between

start hanging laundry on the line. He says he’s

working on a very long thread on a spool, which would actually

let you converse as you walk around the street. Like I’m

going to hold my breath waiting for that one. He asked me what

I was doing wasting my time with rocks, anyway, when I could

building things he called ‘aeroplanes’. He told

me he was undecided about what to paint on the part he called

the ‘fuselage’ — an eagle carrying lightning

bolts in its talons or a chubby women with a smiling face. I

suggested a smiling woman holding lightning bolts. He was not

amused. A weird man, Leo. Frankly, I don’t think

the old geezer is playing with a round boccie ball,

anymore. But time will tell.

|

I'll see

your metafour and raise you five.

Risorgimento

Garibaldi's

triumphant entry into Naples

|

I had lunch

today with a 95-year-old gentleman named Franco. He told me that his

father passed away in the 1950s, also at a ripe old age. We did some

quick figuring and determined that his father was born in 1867. That

was the year that Marx published Das Kapital, the year in which

The Beautiful Blue Danube was played for the first time, and

the year in which the British North American Act created the Dominion

of Canada. The typewriter was invented in 1867 and it was the year that

Czar Alexander II sold Alaska to the United States. Rome was not yet

the capital of a united Italy. I was one generation removed from all

that. (Somehow, all that makes me feel very young rather than very old.

That seems strange.)

I am in

the midst of a "pump the elderly for information" campaign about the

situation in southern Italy following the unification of Italy—that

is, in the decade following the unification in 1861, the year in which

Piedmont, Lombardy, Parma, Modena, Lucca, Romagna, Tuscany, and the

former Kingdom of the Two Sicilies (of which Naples was the capital)

were united under Piedmont's Victor Emmanuel II to form the modern nation

state of Italy. (Rome would become the capital in 1870).

The reason

for my campaign is the few enquiries I have received about northern

mistreatment of the south following unification—or—to use

the terminology of those southerners who express themselves vehemently

about that period, the "rape of the south". There certainly is no shortage

of material in Naples on the subject. I have even seen a book about

"the Savoy concentration camps," in which the title uses the Nazi term

"Lager" (from Konzentrationslager) just so you don't miss

the point. I am looking now at a book entitled They Were the Real

Bandits, those Brothers of Italy. The title contains an allusion

to the first line of the Italian national anthem, known as The Hymn

of Mameli (after the author of the text, Goffredo Mameli, 1827-49).

The line starts, "Fratelli d'Italia…" (Brothers of

Italy), that phrase being the alternate title of the anthem, itself.

The music is by Michele Novaro (1818-85). This particular book is a

condemnation of all the figures popularly connected with the Risorgimento,

the movement to unify Italy; that is, Garibaldi is little more than

a thug in charge of a band of mercenaries, all in the hire of northern

hyenas such as Cavour and Victor Emmanuel II. The defeat of the Kingdom

of the Two Naples (The Kingdom of Naples) by the forces of Garibaldi

and Victor Emmanuel was the beginning of mass unemployment and general

misery for the south and the beginning of immigration away from the

former Kingdom of Naples, thus depleting its greatest resource, people

who want to work. And so on and so forth.

I didn't

get much from Franco, except something I already knew—the Risorgimento

is sacrosanct in modern Italian history. You may take issue with the

way it was done—that is, you may say something like "The unity

of Italy (Risorgimento) was inevitable, but perhaps the invasion

and conquest of the south was not. Maybe it could have been handled

in another way."—but you can't argue with the premise that Italy

was to be one. The term, itself—Risorgimento—rebirth,

resurgence, resurrection (all that)—is the name that Cavour gave

to the newspaper he founded in 1849. In the opening paragraph of the

first issue, he spoke of the need for a "political and economic risorgimento".

The name stuck and became the name of the movement, itself, to unify

Italy.

It would,

however, be a mistake to view that movement strictly as the idea of

northerners such as Garibaldi, Cavour, and Mazzini. Indeed, much of

the philosophy underlying Italian unity comes from the south, from the

members of the so-called Neapolitan Enlightenment such as Vincenzo Cuoco. Indeed, the first secret societies

agitating for unity were the "carbonari", a southern invention. Thus, the drive

to unity was broadbased. Could it have been achieved in any other way

than by an invasion of the south? (The what-if school of history is

always fun!) It turns out that on a least two occasions, Victor Emmanuel

proposed an alliance with the Kingdom of Naples. He and the Neapolitans

would divvy up the peninsula. Since this would entail taking over the

Papal States (except for the city of Rome, itself), the King of Naples

turned down the proposal as blasphemous. And, thus, Garibaldi did what

he did—invaded Sicily and then

the Italian mainland. He disobeyed Victor Emmanuel, by the way. "Don't

invade the mainland," was the order. Garibaldi wrote a nice note, asking

for permission to "disobey". It is not clear that he waited for the

return mail.

Thus—according

to these books I am looking at—began a ten-year period of intense

suffering for the south: looted treasury, industrial plants carried

off, unjust imprisonment and even execution of Neapolitan citizens,

etc. As I say, Franco was no help, other than to tell me that his grandfather—born

in the 1840s—was a proud member of the Bourbon army of the Kingdom

of Naples. I have one more gentleman on my list of those to be pumped.

He is 105 years old. He is in good health, but now says he is feeling

tired. Lunch next week—I hope—but I have the feeling that

I may have to find a real historian.

Miseno

The woman next to me was complaining that "the ruins we saw in Libya

are much better preserved than these." We were standing in what

amounts to ruins of ruins of ruins at Miseno, at the extreme western

end of the Gulf of Naples, in the middle of what used to be Portus Iulius, the home port for the western Imperial

fleet under Caesar Augustus. She was right, of course, but then antiquity

holds up pretty well in the desert air. Libya, too, is about six times

larger than all of Italy and has fewer people in it than I can see from

my balcony in Naples. The woman next to me was complaining that "the ruins we saw in Libya

are much better preserved than these." We were standing in what

amounts to ruins of ruins of ruins at Miseno, at the extreme western

end of the Gulf of Naples, in the middle of what used to be Portus Iulius, the home port for the western Imperial

fleet under Caesar Augustus. She was right, of course, but then antiquity

holds up pretty well in the desert air. Libya, too, is about six times

larger than all of Italy and has fewer people in it than I can see from

my balcony in Naples.

The specific

ruins she was groaning about are a theater, at one time an amphitheater

with the spectator seats—row upon row—set in the side of

the cliff overlooking the outer harbor of the port—now called

"Lake Miseno," such that the spectators had their backs to the hillside

and, beyond the cliff, the water. Of course, we couldn't see any of

that because the concave recess that was once the amphitheatre is full

of modern houses, some of which actually incorporate Roman masonry.

We were actually in the manmade cavern beneath the theater, a passageway

running the perimeter of the semicircular structure above and—two-thousand

years ago—allowing entrance from the waterfront, itself. In order

to get in there, we walked through someone's front yard and down some

stairs by the driveway and garage. (Presumably a concession the owner

has to make to the Ministry of Culture for being permitted to have his

bathroom take up aisle IV, seats XII through XXVI.)

Part of

the problem—no, all of the problem—is that very little of

this was discovered until the 1960s, when overbuilding went absolutely

wild, what with everyone wanting to ride the Italian economic miracle

to the outskirts and live high up overlooking the bay where, yea, brave

Ulysses sailed, and only a few hundred yards from where some of the

juiciest parts in The Aeneid are supposed to have played

out.

Archaeologists

have discovered and excavated what is left of a sacello (a small

shrine, see photo, above) built to Caesar Augustus, but any appreciation

of that, as well, has to contend with adjacent apartments. Certainly,

in an area of Italy with abundant and open displays of ancient Rome,

such as Pompeii and Herculaneum, and even ancient Greece, such as Cuma

and Paestum, it is strange to prop yourself up against a bus-stop so

you can try to shoot around the rubbish bin for a good shot of a shrine

to the emperor.

Relatively

unspoiled, however, and high at the top of the cliff over the bay is

the Cento Camarelle -the One Hundred Little Rooms (photo, left)-

a group of cisterns arranged on two levels oriented at right-angles

to each other. Whether or not there are really one-hundred chambers,

I don't know, but the entire labyrinth is impressive and cut out of

the tuff of the cliff. The passageways between the individual cisterns

are narrow and none of the entire affair is for the claustrophobic.

The walls are still plastered with the waterproof plaster called

cocciopesto and there are graffiti on those walls from those

who have visited before you. One I saw was from "1737". Besides the

two accessible levels, there is evidence of another one even deeper.

The great Neapolitan archaeologist, Amedeo Maiuri, suggested that much

of the structure was originally a basement of sorts for a private villa,

possibly that of the orator Quintus Hortensius Ortalus (114–50

b.c), public-speaking rival of Cicero, himself. That is speculative,

of course, but, in any event, that would place any private villa on

the spot well before the time at which the premises were eventually

given over to the service of the later imperial port under Augustus. Relatively

unspoiled, however, and high at the top of the cliff over the bay is

the Cento Camarelle -the One Hundred Little Rooms (photo, left)-

a group of cisterns arranged on two levels oriented at right-angles

to each other. Whether or not there are really one-hundred chambers,

I don't know, but the entire labyrinth is impressive and cut out of

the tuff of the cliff. The passageways between the individual cisterns

are narrow and none of the entire affair is for the claustrophobic.

The walls are still plastered with the waterproof plaster called

cocciopesto and there are graffiti on those walls from those

who have visited before you. One I saw was from "1737". Besides the

two accessible levels, there is evidence of another one even deeper.

The great Neapolitan archaeologist, Amedeo Maiuri, suggested that much

of the structure was originally a basement of sorts for a private villa,

possibly that of the orator Quintus Hortensius Ortalus (114–50

b.c), public-speaking rival of Cicero, himself. That is speculative,

of course, but, in any event, that would place any private villa on

the spot well before the time at which the premises were eventually

given over to the service of the later imperial port under Augustus.

Aragonese Naples—

The

white section between the towers is called

the Aragonese Victory Arch

"I

wonder how they got in! " people would say. It had worked for

the Greeks against the Trojans and it had even come off once before

in this very city of Naples back in the 6th century when

the Byzantine general Belisarius sneaked his men past the city walls

through an aqueduct. Now it was going to work again; Alfonso's cohorts

within the city opened the passage and let the invaders in. And just

as under Belisarius, the subsequent sacking and pillaging was atrocious,

but Naples was now rejoined to Sicily, unifying the Kingdom of Two Siciles

for the first time in two hundred years. Afterwards, Alfonso went back

outside so he could enter the city officially on 26 February 1443

in a golden chariot and sheltered by a canopy held by 30 disgruntled

Neapolitan noblemen. That entry is memorialized in the Aragonese victory

arch over the entrance to the Maschio Angioino , the Angevin Fortress (photo, left).

It was a task they did not like, for a king they did not like, at the

beginning of a dynasty they would not like. Shortly thereafter, Alfonso

left his Spanish holdings to his brother and dedicated himself full-time

to his own Aragonese dynasty in Italy. "I

wonder how they got in! " people would say. It had worked for

the Greeks against the Trojans and it had even come off once before

in this very city of Naples back in the 6th century when

the Byzantine general Belisarius sneaked his men past the city walls

through an aqueduct. Now it was going to work again; Alfonso's cohorts

within the city opened the passage and let the invaders in. And just

as under Belisarius, the subsequent sacking and pillaging was atrocious,

but Naples was now rejoined to Sicily, unifying the Kingdom of Two Siciles

for the first time in two hundred years. Afterwards, Alfonso went back

outside so he could enter the city officially on 26 February 1443

in a golden chariot and sheltered by a canopy held by 30 disgruntled

Neapolitan noblemen. That entry is memorialized in the Aragonese victory

arch over the entrance to the Maschio Angioino , the Angevin Fortress (photo, left).

It was a task they did not like, for a king they did not like, at the

beginning of a dynasty they would not like. Shortly thereafter, Alfonso

left his Spanish holdings to his brother and dedicated himself full-time

to his own Aragonese dynasty in Italy.

Neapolitans

always considered Alfonso a foreigner, particularly because of his habit

of surrounding himself with only his own countrymen and giving them

the choice positions at court. Apparently, towards the end of his life

he changed his mind about this and passed on to his son a few

bits of advice: avoid the Spanish, lower the taxes and keep on good

terms with the princes in Italy, especially the Popes. Alfonso was regarded

as a cultured person; he founded an excellent library, and artists,

poets, philosophers and scholars were an integral part of his court.

In the field with his troops, he lived the same life as his men and

exposed himself to danger in battle with no regard for his own

personal safety. They say he also went among the common people incognito

to find out how things were going. He liked to listen rather than

talk and claimed to be a simple person, once saying he would have been

a hermit if he had had his choice in life.

Alfonso

of Aragon

Because

of his patronage of the arts he became known as Alfonso the Magnanimous.

He also started the total rebuilding of the Angevin Fortress, fallen

into ruin since its completion in the late 1200s; he paved the

streets of the city, cleaned out the swamps and greatly enlarged the

wool industry that had been introduced by the Angevins. In spite of

his pretensions to simplicity, however, he was addicted to splendor.

At a Neapolitan reception for Frederick III of Germany, the order of

the day to all the artisans in the Kingdom was to give Frederick's men

whatever they wanted and send Alfonso the bill. Then they all went hunting

in the great crater known as the Astroni in the Phlegrean

Fields and had a banquet at which wine flowed down the slopes and

into the fountains for the guests. Parties, however, did not prevent

Alfonso, by the time of his death in 1458, from also having developed

the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies into the foremost naval power in the

western Mediterranean. Because

of his patronage of the arts he became known as Alfonso the Magnanimous.

He also started the total rebuilding of the Angevin Fortress, fallen

into ruin since its completion in the late 1200s; he paved the

streets of the city, cleaned out the swamps and greatly enlarged the

wool industry that had been introduced by the Angevins. In spite of

his pretensions to simplicity, however, he was addicted to splendor.

At a Neapolitan reception for Frederick III of Germany, the order of

the day to all the artisans in the Kingdom was to give Frederick's men

whatever they wanted and send Alfonso the bill. Then they all went hunting

in the great crater known as the Astroni in the Phlegrean

Fields and had a banquet at which wine flowed down the slopes and

into the fountains for the guests. Parties, however, did not prevent

Alfonso, by the time of his death in 1458, from also having developed

the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies into the foremost naval power in the

western Mediterranean.

Alfonso's

illegitimate son, Ferrante, succeeded him, and in spite of extreme hostility

on the part of the feudal lords in the kingdom, succeeded in strengthening

the monarchy at their expense. He also drove the Angevin fleet from

Ischia, their last stronghold in the area. Ferrante countered baronial

hostility most violently. To show the barons that feudalism was truly

dead he made a lot of them dead, by doing things such as inviting

them to weddings and then arresting, jailing and executing a number

of them. They say that some were fed to a crocodile that prowled the

dungeon. (A skeleton of one such reptile hung over the arch in the Castle

until quite recently.) He even mummified some of his late enemies and

kept them on display in the dungeon of the Castelnuovo (the alternate

name for the Maschio Angioino, meaning, simply "New Castle",

thus distinguishing it from the older Castel

dell'Ovo, the Egg Castle).

A sigh

of relief went up from the landholding class when Ferrante died in 1494

after 28 years on the throne. It had been a time of intrigue that included

on-again / off-again relations with the Church and even a short-lived

treaty with the feared Turks who were raiding up and down the Italian

coasts. The point of the treaty had been to warn the rest of Italy to

the north not to take the Kingdom of Naples for granted. (The Ottoman

Turks had just overrun the Byzantine Empire and were threatening Rome,

itself.)

Charles

VIII

The French

reappeared with designs on the throne of Naples. Under Ferrante's

successor, Neapolitan resistance to the French was utterly ineffective

and the French, under Charles VIII, took the city virtually unopposed;

indeed, they were welcomed by most of the nobility, who sensed

a chance to recoup their losses. Their toadying didn't work. The French

pillaged the city, anyway, and dispossessed a number of the nobles.

Charles, however, suddenly found himself cut off: The Papal State, Milano,

and Venice —which had just let Charles pass through unhindered

on the way to Naples— suddenly formed an alliance behind and against

him. Charles had to fight his way back home, attempting along the way,

and failing, to bribe the Pope into crowning him King of Naples. The

jibe by historians is that the French brought two things back from their

Italian campaign: the Renaissance and syphilis, one of which history

has dubbed morbus gallicus in their honor. The French

reappeared with designs on the throne of Naples. Under Ferrante's

successor, Neapolitan resistance to the French was utterly ineffective

and the French, under Charles VIII, took the city virtually unopposed;

indeed, they were welcomed by most of the nobility, who sensed

a chance to recoup their losses. Their toadying didn't work. The French

pillaged the city, anyway, and dispossessed a number of the nobles.

Charles, however, suddenly found himself cut off: The Papal State, Milano,

and Venice —which had just let Charles pass through unhindered

on the way to Naples— suddenly formed an alliance behind and against

him. Charles had to fight his way back home, attempting along the way,

and failing, to bribe the Pope into crowning him King of Naples. The

jibe by historians is that the French brought two things back from their

Italian campaign: the Renaissance and syphilis, one of which history

has dubbed morbus gallicus in their honor.

France

then tried something else: the proposal of an Alliance to Ferdinand

of Spain against Spain's own Aragonese relatives in Naples, by virtue

of which the Kingdom of Two Sicilies would cease to exist and be divided

between Ferdinand and Charles. This would effectively give them both

one less rival realm in the area, as well as squelch the heresy that

it wasn't nice to carve up one's own cousins. Ferdinand went for it

and even Machiavelli, himself, later said that Ferdinand had certainly

needed no lessons from anyone in ruthless princemanship. The pact

of Granada was signed on November 11, 1500; the Kingdom was to be divided,

with the capital, Naples, going to France. The French reentered Naples

in July 1501. It now seemed, however, that both France and Spain

had had their fingers crossed at the signing of the original treaty,

so they had a war over it and Spain won. In May 1504, Spanish troops

evicted the French and entered Naples, ending the Aragonese dynasty,

and the Kingdom, intact, became a colony of Spain.

Naples

was now no longer the capital of its own realm. In a few year's time,

with Charles V of Spain crowned Holy Roman Emperor, heir to the Caesers

and Charlemagne, it would be part of an empire, as it had been

more than a thousand years earlier. True, the East had fallen and

what was left of Christian Empire was all in the West; but after 1492,

"West" meant something monumentally different in human history. The

Empire had shifted, spreading from Europe to the Americas

and on to the Pacific. The age of Empires on which "the sun never sets"

had arrived.

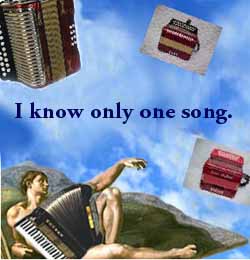

Gypsies

(1)

I

gave a few cents to a gypsy kid who was playing the accordion on the

subway this evening. He wasn't all that bad. He looked to be about 15

or 16 and played a good, competent version of a Russian folk song, the

name of which I don't remember. He smiled as he played and was not oppressively

obnoxious about trying to wheedle money out of you. I

gave a few cents to a gypsy kid who was playing the accordion on the

subway this evening. He wasn't all that bad. He looked to be about 15

or 16 and played a good, competent version of a Russian folk song, the

name of which I don't remember. He smiled as he played and was not oppressively

obnoxious about trying to wheedle money out of you.

There didn't

used to be any accordion players in Naples. Now they are a major import

item and seem to be in all the trains. The real reason I gave the kid

some money was to reward him for being the first gypsy squeeze-boxer

I have heard who has not played that annoying "Anniversary Waltz". It

seems to be the only song they know, and most of them never get past

the first 16 measures— "Oh, how we danced on the night we were

wed/ We vowed our true love, though a word wasn't said…" Then

they diddle around, lose the rhythm, play some wrong notes and start

again.

I wonder

if they are real gypsies from Romania. That song is known as The

Anniversary Waltz (or Song) to English-speaking audiences

and bears the names of Al Jolsen and Saul Chaplin on the music. Jolsen

recorded it in 1946. It is, however, "borrowed" from the music of Josef

Ivanovici, a Romanian composer (1845-1906); it is part of his Waves

of the Danube waltz suite.

Cops,

undercover

Today

was the beginning of Operation "High Impact". There were so many "Forces

of Order" (as Italian so wishful-thinkingly dubs the various branches

of law enforcement)—also known as "cops" for purposes of this

brief discussion—on the streets of downtown Naples this morning

that at least a few bad guys were scared off and most tourists thought

they had wandered onto the set of Rambo XII. Today

was the beginning of Operation "High Impact". There were so many "Forces

of Order" (as Italian so wishful-thinkingly dubs the various branches

of law enforcement)—also known as "cops" for purposes of this

brief discussion—on the streets of downtown Naples this morning

that at least a few bad guys were scared off and most tourists thought

they had wandered onto the set of Rambo XII.

These weren't

delicate traffic cops handing out tickets. They wore flak jackets and

carried automatic weapons. The pulled over suspicious looking cars,

and the word is that they confiscated all sorts of contraband by so

doing; also, they turned up a lot people without driving licenses or

documents and a few out driving around who should apparently have been

at home since they were under house arrest for some reason. I did see

one bored and heavily-armed cop stop an attractive young woman on a

motorcycle because she wasn't wearing a helmet. The gist of the conversation

was that he would really hate to see something terrible happen to her

beautiful head just because she forgot her helmet. All smiles and friendly

words. No ticket, though maybe a phone number was passed.

The best

part is the "Hawks"—undercover cops. They wear civvies, always

travel in pairs and are always mounted on ridiculously overpowered motorcycles.

If you are a punk purse-snatcher on a 100 cc Vespa, lots of luck. Just

one "Hawk" looks like two longshoremen; they are unshaven; they scowl

a lot; and in the warmest weather, they wear some sort of jacket or

maybe a bush vest with lots of pockets all the better to conceal the

heat they are packing. Tough customers. Tourists move away from them

because they look like criminals and criminals move away from them because

they look like undercover good guys. They are about as undercover as

a cat-burglar in black leotards and a ski-mask.

Nisida

(1); Poerio, Carlo

Quite by accident, I discovered a connection between two unrelated

items (or so I thought) in Naples today. The tiny island off the tip

of Cape Posillipo is named Nisida. The original Greek settlers of the

area called this small island Nesis. The Romans called it Nisida.

It is here that Brutus plotted the assassination of Julius Caesar, and

it is here that Cicero says apud illum multas horas in Néside—that

he had a long talk with Brutus after the assassination to discuss the

future of Rome. In the 1800s Nisida was the site of a Bourbon prison,

then an Italian state penitentiary, and, now, a reformatory for juvenile

offenders. Quite by accident, I discovered a connection between two unrelated

items (or so I thought) in Naples today. The tiny island off the tip

of Cape Posillipo is named Nisida. The original Greek settlers of the

area called this small island Nesis. The Romans called it Nisida.

It is here that Brutus plotted the assassination of Julius Caesar, and

it is here that Cicero says apud illum multas horas in Néside—that

he had a long talk with Brutus after the assassination to discuss the

future of Rome. In the 1800s Nisida was the site of a Bourbon prison,

then an Italian state penitentiary, and, now, a reformatory for juvenile

offenders.

Statue

of Carlo Poerio in Piazza S. Pasquale

In the early

1900s Nisida suffered two indignities: one, it was joined to the mainland

by a causeway, and, two, it was encroached upon by the unsightly steel

industry in Bagnoli. That patch of industrial blight is (as of 2002)

a thing of the past, as the Campania region and the city of Naples pursue

plans to rejuvenate the entire Bagnoli area. Most of the physical plant

of the ex-steel mill has already been torn down, and there is already

a thriving "Science City" fair ground on the premises in Bagnoli. Currently,

part of the island of Nisida is also home to the administrative headquarters

of NAVSOUTH, the naval forces for NATO's Southern Command. Also, there

is currently some hope of luring the next America's Cup to the area.

That would require major investment in port facilities. At present,

there is a small port for pleasure craft, and that is where I found

myself this morning, helping my friend, Bill, get his splendid sailboat,

Down East, into the water and noticing how uneasy I am with such

phrases as "Avast!" "Belay that!" and "Batten down the hatches!" ("Stand

by to repel boarders!" did give me a thrill just to pronounce, though.

I think it even shivered my timbers.) In the early

1900s Nisida suffered two indignities: one, it was joined to the mainland

by a causeway, and, two, it was encroached upon by the unsightly steel

industry in Bagnoli. That patch of industrial blight is (as of 2002)

a thing of the past, as the Campania region and the city of Naples pursue

plans to rejuvenate the entire Bagnoli area. Most of the physical plant

of the ex-steel mill has already been torn down, and there is already

a thriving "Science City" fair ground on the premises in Bagnoli. Currently,

part of the island of Nisida is also home to the administrative headquarters

of NAVSOUTH, the naval forces for NATO's Southern Command. Also, there

is currently some hope of luring the next America's Cup to the area.

That would require major investment in port facilities. At present,

there is a small port for pleasure craft, and that is where I found

myself this morning, helping my friend, Bill, get his splendid sailboat,

Down East, into the water and noticing how uneasy I am with such

phrases as "Avast!" "Belay that!" and "Batten down the hatches!" ("Stand

by to repel boarders!" did give me a thrill just to pronounce, though.

I think it even shivered my timbers.)

Later in

the day, I was looking for an address on via Poerio in Naples.

Now, just as you can get lost in Naples by going to the wrong via

Caracciolo (see here), so, too, can

you wind up on the wrong via Poerio. There is one named for Carlo

Poerio (1802-67) and another for Alessandro Poerio (1802-1848). They

were brothers, both intimately connected with the Risorgimento,

the political movement to unify Italy. Interestingly, their father,

Giuseppe Poerio (1775-1843) was a supporter of the Neapolitan Republic

of 1799, for which he was sentenced to life in prison. A family of trouble-makers,

clearly.

On

the slopes of the Nisida crater are the ruins of what is thought

to be the villa of Brutus. In the background are the town

of Bagnoli, then Cape Posillipo, then Mt. Vesuvius in the distance.

|

In

1849, Carlo Poerio was sentenced by the Bourbon court of Naples to 24

years at hard labor for his part in the political turmoil in Naples

of the previous year. He was sent to—here is the connection—Nisida.

He and other prisoners were confined in such miserable conditions that

William Gladstone, after a visit to the prison in 1851, felt compelled

to write his two Letters to the Earl of Aberdeen on the State Prosecutions

of the Neapolitan Government. In these letters, Gladstone coined

the now famous description of the Kingdom of Two Sicilies as "the negation

of God erected into a system of Government." Indignation throughout

Europe was partially responsible for Poerio's release in 1858. He was

exiled but returned to Italy in 1861. He died that year in Florence.

[For more on the Gladstone "Letters...," click

here.] In

1849, Carlo Poerio was sentenced by the Bourbon court of Naples to 24

years at hard labor for his part in the political turmoil in Naples

of the previous year. He was sent to—here is the connection—Nisida.

He and other prisoners were confined in such miserable conditions that

William Gladstone, after a visit to the prison in 1851, felt compelled

to write his two Letters to the Earl of Aberdeen on the State Prosecutions

of the Neapolitan Government. In these letters, Gladstone coined

the now famous description of the Kingdom of Two Sicilies as "the negation

of God erected into a system of Government." Indignation throughout

Europe was partially responsible for Poerio's release in 1858. He was

exiled but returned to Italy in 1861. He died that year in Florence.

[For more on the Gladstone "Letters...," click

here.]

Swiss

in Naples

In

the 1949 thriller, The Third Man, Orson Welles' character, Harry

Lime, delivers a short monologue on Switzerland: In

the 1949 thriller, The Third Man, Orson Welles' character, Harry

Lime, delivers a short monologue on Switzerland:

| In

Italy for thirty years under the Borgias they had warfare, terror,

murder, bloodshed —but they produced Michelangelo, Leonardo

da Vinci, and the Renaissance. In Switzerland they had brotherly

love, 500 years of democracy and peace, and what did that produce?

The cuckoo clock. |

With all

due respect to Welles (he wrote that part of the script, himself),

the idea that the Swiss are a peaceful race of bankers, yodellers,

and clock makers is wrong. In modern-day Switzerland, every male who

is upright and breathing is in the army until the age of 50. They

all keep their military-issue weapons at home, and, I suspect, rank

high in the world on the firearm-per-square-person index.

True, when

one thinks of Swiss soldiers and Italy, the colourful Swiss guards in

the Vatican in their 16th–century uniforms pop to mind (photo,

left below). Yet, behind today's quaint picture of comic-opera irrelevance

is a very long and violent history of Switzerland as the single greatest

provider of mercenary soldiers in Europe. Between the Battle of Nancy

in 1477 and 1874, when the Swiss constitution forbade the practice,

regiment after regiment of Swiss soldiers fought on battlefields elsewhere

in Europe. These were not individual "hired guns," but entire regular

Swiss regiments contracted out by their respective cantonal governments

to serve abroad in return for large sums of money, a substantial part

of the income in a canton in any given year. In 400 years of mercenary

service, Switzerland hired out some two million soldiers and 70,000

officers.

The contracts

were typically between a canton and a particular monarch, whom the Swiss

were then expected to serve faithfully, no matter what. For that reason,

you always have Swiss Guards on the side of established order and never

on the side of revolution. One famous episode was during the defence

(Aug. 10, 1792) of the Tuileries palace in Paris during the French Revolution.

Louis XVI ordered the Swiss Guard not to fire on the crowd, which, at

the goading of George Danton, stormed the palace and massacred 600 of

them, anyway. The contracts

were typically between a canton and a particular monarch, whom the Swiss

were then expected to serve faithfully, no matter what. For that reason,

you always have Swiss Guards on the side of established order and never

on the side of revolution. One famous episode was during the defence

(Aug. 10, 1792) of the Tuileries palace in Paris during the French Revolution.

Louis XVI ordered the Swiss Guard not to fire on the crowd, which, at

the goading of George Danton, stormed the palace and massacred 600 of

them, anyway.

The Swiss

were very active in Naples from the beginning of the Bourbon rule in

the 1730s right up until the final defence of the Kingdom of Two Sicilies

at the siege of Gaeta in 1860. Their first contract with Naples was

in 1731 with Charles III of Bourbon and

by the mid-1800s there were four regiments (about 7,500 men) of Swiss

on constant service in the Kingdom of Naples.

The Swiss

were important in the Kingdom of Naples in the turbulent year of 1848,

when calls for reform and revolution swept virtually all of Europe.

In January of that year, there was an uprising in Sicily, and a call

for the restitution of their constitution of 1812. (In that year, the

mainland portion of the Kingdom of Naples was in French hands, under

Murat, while the Bourbon monarchy with their royalist