©

2004 Jeff Matthews & napoli.com

Beverello,

molo (port of Naples)

Directly across

from Maschio Angioino --the gloomy fortress at the port--

is the pier for ferries and hydrofoils. It is named Molo [pier]

Beverello and includes the facility adjacent to it on the east,

the large passenger terminal built in the 1930s (photo). Molo Beverello

handles all of the day traffic to the Sorrentine peninsula, to the islands

of Ischia and Capri, and even car and passenger traffic to Sicily and

Sardinia. It also handles larger vessels on Mediterranean cruises. Directly across

from Maschio Angioino --the gloomy fortress at the port--

is the pier for ferries and hydrofoils. It is named Molo [pier]

Beverello and includes the facility adjacent to it on the east,

the large passenger terminal built in the 1930s (photo). Molo Beverello

handles all of the day traffic to the Sorrentine peninsula, to the islands

of Ischia and Capri, and even car and passenger traffic to Sicily and

Sardinia. It also handles larger vessels on Mediterranean cruises.

Adjacent

to Molo Beverello on the west is another pier, Molo S. Vincenzo.

It is little used, simply because it is too small. The city has announced

that it going to dump 94 million euros into that part of the port --

(who knows, perhaps even directly into the water, if some critics of

the plan are to be believed).

Molo S.

Vincenzo -- for some reason-- I think is what has stopped me from ever

getting out onto the main breakwater of the port of Naples. It is very

long and terminates in a lighthouse and a charming statue of San Gennaro,

the patron saint of Naples. Every time I try to gain access to whatever

secret little passageway will get me out on that breakwater, I run afoul

of some "no entry" sign around Molo S. Vincenzo. Yet, whenever I sail

out through the harbor on the way "to smite the sounding furrows and

sail beyond the baths of all the western star", I see people sitting

out there, fishing! They didn't row out there, either, because I can

see their cars parked nearby. They drove out there on the street (of

sorts) that runs the entire length of the breakwater on the sheltered

side.

Whatever

the case, for 94 million euros I want my own entrance. (No doubt, it

will be like the one I refer to in the entry for November 11 (above).

Anyway,

the found an unexploded WW2 bomb at the bottom of the harbor near the

passenger terminal the other day while they were dredging. About five

feet long and two in diameter, the bomb was a reminder of the days when

the entire port section of the city and other strategic sites such as

the train station were the target of Allied air-raids against the Germans,

who were occupying Naples.

The newspaper

article waxed nostalgic about the possibility of still finding

some legible graffiti on the bomb casing, such as "Hey, Benito --This

one's for you!" Alas, there was no such historic drivel; the bomb was

removed by divers of the SDAI (Servizi difesa antimezzi insidiosi)

-- the bomb squad-- and everything returned to normal.

There is

legitimate concern, however, about the next time. There is almost certain

to be a next time, too, since dredging in the harbor will continue for

the planned renovation of a large section of the passenger piers. Also,

construction of new buildings along the entire port-side road, via Marina,

often entails digging way down into terrain perhaps undisturbed since

1943. The entire area was a target, and the chances of coming across

even more unexploded ordinance are high.

The

port of Naples extends to the east for another mile or so. Once past

the main passenger terminal adjacent to Molo Beverello, the facilities

are almost totally given over to container ships and other freighters.

Like any other area that has undergone a century of rebuilding, decay,

bombardment, more decay and more rebuilding, the entire area along the

main road that runs the length of the port is an unbelievable hodgepodge

of architecture.

The

great boom of construction—called the risanamento—at

the turn of the twentieth century tore down the ancient port facilities

in order to build the main road that leads east out of the city. That

construction eliminated all but the most obvious signs that there was

ever an olden Naples in that area; for example, city builders of 1900

left standing a few remnants of the old Carmine Castle across from Piaza

Mercato.

Later

construction during the 1930s is responsible for a number of large buildings

in the port, including the main passenger terminal. The port—especially

the eastern end—was then heavily bombed in WW II. Newer office

buildings put up over the last 20 years along the long portside road

have now repaired much of that damage—if adding to the eye-jolt

of large glass and steel buildings right next to what is left of the

Church of Santa Maria di Portosalvo, built in 1554. The tiny church

was once the spiritual home to many Neapolitan sailors. Outside the

church is a stone cross, a monument to the retaking of the Kingdom of

Naples by the Bourbons in 1799, which episode ended the short-lived

Neapolitan Republic.

Near the church, but across

the main road and within the port itself, at water's edge, is the only

other obvious bit of earlier Naples. It is the old quarantine station

(photo), the Immacolatella, finished in the 1740s. It was built

to the plans of D.A. Vaccaro, the proment painter, scultpor, and architect

whose works are scattered throughout Naples, including the beautiful

majolica-tile courtyard of the Church of Santa Chiara. The Immacolatella

is so-called from the sculpture of the Immaculate Virgin above the facade. Near the church, but across

the main road and within the port itself, at water's edge, is the only

other obvious bit of earlier Naples. It is the old quarantine station

(photo), the Immacolatella, finished in the 1740s. It was built

to the plans of D.A. Vaccaro, the proment painter, scultpor, and architect

whose works are scattered throughout Naples, including the beautiful

majolica-tile courtyard of the Church of Santa Chiara. The Immacolatella

is so-called from the sculpture of the Immaculate Virgin above the facade.

Extensive expansion and modernization of the entire port of Naples will

continue throughout 2004.

University

(2)

I

went out to the new University campus at Monte Sant'Angelo the other

day. It is exactly that: a campus on the US model, a city unto itself

in an area way out in what used to be acres of greenery

on the periphery of Naples in Fuorigrotta in back of the S. Paolo soccer

stadium. I

went out to the new University campus at Monte Sant'Angelo the other

day. It is exactly that: a campus on the US model, a city unto itself

in an area way out in what used to be acres of greenery

on the periphery of Naples in Fuorigrotta in back of the S. Paolo soccer

stadium.

It looks

to be about half-finished and has a futuristic look about it -- lots

of glass and steel, with tubular passages from building to building.

Thus far, the campus houses the departments of physics, chemistry,

biology and computer science -- you know, all the "hard stuff". The

humanities are still back in the middle of

town in converted 14th-century monasteries, no doubt a more

appropriate setting for studying the metaphors of Dante and Boccaccio.

Eventually, however, even students of languages and literature will

move out to the new site. A subway station directly beneath the campus

will link to the main line into the center of town. It's an ambitious

project.

Black market

There

is a bit of unpleasantry going on down at via San Gregorio Armeno, the street in the historic

center of Naples known for the shops that make and sell the wherewithal

for your yearly Christmas presepe, the manger display. There

is a bit of unpleasantry going on down at via San Gregorio Armeno, the street in the historic

center of Naples known for the shops that make and sell the wherewithal

for your yearly Christmas presepe, the manger display.

Legitimate

shops line both sides of the narrow street for the entire block between

via S. Biagio dei Librai and via Tribunali. They are licensed to be

open and do business. They are getting extreme competition from the

many "abusivi" ("those who abuse the law") in the area, itinerant

street vendors selling their own Christmas decorations.

It is no

secret that Naples is a hotbed of blackmarketeering and just plain street-hustling,

people out trying to make a buck. In some cases, these unlicensed vendors

are not so itinerant -- no opening of the jacket to reveal rows of tiny

angels and stars pinned to the lining -- ("Pssst. Hey, buddy -- wanna

buy some tinsel?") They use quickly deployable tables and shelves to

display boxloads of goods right on the open street just feet from legitimate

shops trying to do business. The shopkeepers have complained, and the

police have been moving in to chase off the "abusivi," who have,

in turn, reacted violently by overturning rubbish bins and setting fire

to the contents. Who knows if the situation will settle down in the

coming weeks?

furbone,

motorcycles (2)

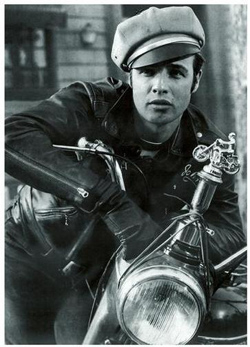

All

I really remember about the great 1953 film, The Wild One, starring

Marlon Brando (photo), was that it was very loud with the sound of motorcycles.

That may have had a certain quaint charm in the early 50s, but not in

2002 and not in Naples. All

I really remember about the great 1953 film, The Wild One, starring

Marlon Brando (photo), was that it was very loud with the sound of motorcycles.

That may have had a certain quaint charm in the early 50s, but not in

2002 and not in Naples.

The other

night, I was third or fourth in line in my car, waiting to turn left

at the light change when a homegrown version of the Black Rebels Motorcycle

Club went screaming by -- about 15 punks on bikes, not one helmet among

them, weaving in and out of traffic and making obscene gestures at all

of us poor saps in cars as they sped right through the intersection

and red-light. No doubt they were on their nefarious way to harass some

cleancut cafe waitress on her way home to Pop. They

all made it through totally unscathed. These are the "furboni" (Big

Clever Ones), those who always get away with everything, and I

thought, "C'mon -- just once. Maybe not under a train, but... some

justice, some moral equivalent of a train." I have only

seen that "just once"—well, just once, in Naples.

I'm stopped

in my little minimobile at a railway crossing. The red warning lights

are flashing and the barrier has just come down in front of me; I am

first in line on my side of the tracks. I resign myself to wasting another

two or three minutes of the paltry few thousand remaining to me. I examine

the barrier on my side. It is a good barrier—imposing, straight

and true, a you-shall-not-pass kind of barrier, if ever there was one.

Casually I glance over at the other side and notice the other barrier.

It is not straight. It has a big peaked bump in the middle—it

looks like the universal symbol at camp grounds which means "You May

Put Your Tent Here." At some time that thing played Guillotine opposite

some poor car's Marie Antionette. This, in itself, makes me smile. This

is not the sense of justice I mentioned a second ago; this is justice's

evil step-sibling, which the Germans so delightfully call Schadenfreude

-- joy at the misfortune of others

Two young

thugs on a motorcycle now roll up to that barrier, having adroitly and

with utter disdain for the laws of Nature, Nature's God, and the Italian

traffic code, zigged and zagged their way around a dozen other vehicles

to get to the front. (It wouldn't be so bad, except that they both have

that perpetual "Don't you wish you were as cool as we are?" smirk frozen

on their totally moronic ratty little punk faces.) They don't ask --

rather, they tell-- the keeper of the barrier that they are going through

anyway, and he glumly glances down the tracks, hoping that the train

isn't close enough to ruin his fatality-free safety record (at least

for the current week). Now, on their side of the tracks they pass rather

nicely under that hump. The driver lowers his head, which isn't too

big, anyway, and he doesn't really have to tilt the bike too much. Moron

number two just slumps down and hangs on.

On my side,

however, things aren't so easy. "My" barrier has no hump and is not

about to let a couple of human snakes like this slither under, no questions

asked. This becomes clear to the "furbone" driver, who now has

to slide out of the saddle to support himself, his machine and passenger

with one leg while he tilts his bike low enough to shimmy under. He

is having difficulty and has put together a combination of stutter-stepping,

shuffling and kick-boxing -- like an alien auditioning for Saturday

Night Fever. He is not amused and is visibly irritated at

the fact that his audience --me included --is watching him lose his

cool. In fact, his cool is about to turn to small puddles, since there

is a train approaching.

In the

meantime, "furbone" number two, the passenger, in an attempt to help,

actually stands up from the passenger seat as the bike lists low to

the ground. Both his feet are on the ground (where his knuckles usually

drag), and this, of course, takes some weight off the bike, enabling

the driver to wriggle under. He does so. Then he straightens up in the

saddle, gives a satisfied ego-vrooom! on the controls and roars

off. Not until he turns his head— twenty yards down the road—to

have a nice collective laugh with his friend at the expense of all of

us still waiting for the train to pass, does he realize that his co-moron

is still standing inside the barrier, knees still bent, arms outstretched,

looking like a water-skier waiting to get up.

The skier

scurries under the barrier to get out of the way of the train. His ride

turns around and comes back to get him, and they both have to put up

with a chorus of hooting, honking and laughing -- derision much more

painful to them, I can well imagine, than being flattened by a million

tons of metal. They had been caught being uncool. The train didn't get

them. It wasn't real justice -- but it was close enough.

Magna Grecia

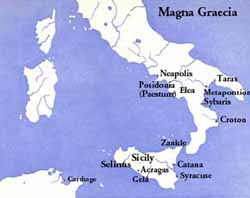

| The

map shows the extensive network of Greek cities in southern

Italy during the age of Magna Grecia. The first settlement was

on the island of Ischia. That settlement then moved across to

the mainland and founded Cuma. (More in the map

section.) |

Shortly

after the year 800 b.c.—and lasting for about three-hundred

years—the peoples of the Aegean peninsula and archipelago, collectively

"Hellenes"—"Greeks"—but individually Chalcidians, Euboeans,

Messenians, Achaeans, Spartans, Ionians and Peloponnesians, spread

to the west and colonized portions of Sicily and the southern Italian

peninsula. Those settlements made up what was known as Magna Grecia

—Greater Greece— and within its borders there arose great

centers of Hellenic culture. In what would one day be "Italy," towns

such as Cuma, Naples, Paestum, Siracuse, Taranto, Metaponte and Croton

became marketplaces for the science and philosophy of Archimedes,

Pythagoras and Plato, ideas which survived the demise of Magna

Grecia, itself, and so influenced its Latin conquerors that today

most Europeans and descendants of Europeans regard themselves as inheritors

of a wondrous hybrid culture called "Greco-Roman". Shortly

after the year 800 b.c.—and lasting for about three-hundred

years—the peoples of the Aegean peninsula and archipelago, collectively

"Hellenes"—"Greeks"—but individually Chalcidians, Euboeans,

Messenians, Achaeans, Spartans, Ionians and Peloponnesians, spread

to the west and colonized portions of Sicily and the southern Italian

peninsula. Those settlements made up what was known as Magna Grecia

—Greater Greece— and within its borders there arose great

centers of Hellenic culture. In what would one day be "Italy," towns

such as Cuma, Naples, Paestum, Siracuse, Taranto, Metaponte and Croton

became marketplaces for the science and philosophy of Archimedes,

Pythagoras and Plato, ideas which survived the demise of Magna

Grecia, itself, and so influenced its Latin conquerors that today

most Europeans and descendants of Europeans regard themselves as inheritors

of a wondrous hybrid culture called "Greco-Roman". Driven

by the need for trade and the desire to set up relations with the Etruscans

of the central and northern Italian peninsula, Euboeans founded the

first colony of Magna Grecia, Pithecussae, on what is now called the

island of "Ischia" in c. 750 b.c. Shortly thereafter, they moved to

the mainland and founded Cuma. They were

followed by the Chalcidians at Zancle (modern "Messina") on Sicily;

then, also on Sicily, the Corinthians founded Siracuse, which would

develop into one of the great cities in the ancient Greek world. Back

on the mainland, along the bottom of the boot, the Aecheans founded

Metapotum and Croton, and the Spartans settled at Tarantum. Within a

century of the first colony at Ischia, the Greeks had established themselves

as a powerful trading bloc in southern Italy and were already being

jealously watched by the Carthaginians and Phoenicians. Naples, itself—somewhat

late in the scheme of Magna Grecia— was founded as "Parthenope"

in the 6th century b.c. It was a second-generation colony, in that it

was settled by the Euboeans of Cuma just to the north, people who by

now no doubt thought of themselves simply as "Cuman"'. They rebuilt

somewhat inland a few years later and called it New City, Neapolis—Naples.

The last important Greek colony to be founded in Italy was Acgragas

(modern Agrigento) in 580 b.c.

Many

of the cities of Magna Grecia that have since drifted into obscurity

are as old as Athens, itself, and—if history had been different—might

have spawned Golden Ages of their own that we would be reading about

in history books today. That was not to be, however, for a number of

reasons. One of them was that although the atmosphere in Magna Grecia

is said to have been somewhat freer than in Greece, politically it suffered

from the same fragmentation as the homeland. The settlements of Greater

Greece were independent and autonomous, and, like the city-states of

Greece, they spent much of their time fighting each other. Between warring

among themselves and fighting to subdue the native populations of Sicily

and the southern Italian mainland, it is no wonder that Magna Grecia

never managed to present a united front against those who, in historical

hindsight, were or would become their true enemies—Carthage and,

of course, Rome. Many

of the cities of Magna Grecia that have since drifted into obscurity

are as old as Athens, itself, and—if history had been different—might

have spawned Golden Ages of their own that we would be reading about

in history books today. That was not to be, however, for a number of

reasons. One of them was that although the atmosphere in Magna Grecia

is said to have been somewhat freer than in Greece, politically it suffered

from the same fragmentation as the homeland. The settlements of Greater

Greece were independent and autonomous, and, like the city-states of

Greece, they spent much of their time fighting each other. Between warring

among themselves and fighting to subdue the native populations of Sicily

and the southern Italian mainland, it is no wonder that Magna Grecia

never managed to present a united front against those who, in historical

hindsight, were or would become their true enemies—Carthage and,

of course, Rome.

In the

4th century b.c., with Alexander the Great looking to the east to conquer

the civilized world of his day, the Persian Empire, the settlements

of Magna Grecia were, more or less, on their own. Sicily had become

the most powerful city-state of Magna Grecia by that time, and its ruler,

Dionysius, tried to establish a single Empire of Magna Grecia starting

in 400 b.c. It was, in a way, quite like Phillip of Macedonia's (Alexander's

father) plan to unify Greece, itself. A united southern Italy might

have been a forerunner of, or maybe —if we play the 'what-if'

game of history— a substitute for the Roman Empire, itself. Alas

for Dionysius and his less capable successors, they couldn't fend off

the Carthaginians or the increasingly belligerent native tribes of Italy.

When one of these tribes, the Romans, took Taranto in 272, b.c. Greek

history in Italy was overwhelmed by the onrush of Roman history. Magna

Grecia was at an end.

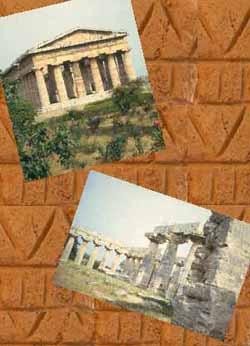

In Naples

you are in Magna Grecia. The Archaeological Museum is, appropriately, at what

was once the northwest corner of the original wall of the city, 2,500

years ago. A few blocks away you can still find part of that wall, and

you can walk the grid of the original streets. They're covered with centuries

of other stone and decades of asphalt, but they're down there. Also,

on the isle of Megaride, the site of the so-called Castel

dell'Ovo, you are on the site of the original city of Parthenope.

A little further afield, the ruins of Cuma

and Paestum can give you insight into what happens to

cities when people don't live in them for a few thousand years. And,

as a final note to what is left of Greater Greece in our immediate area,

there are the ruins, discovered in this century a bit south of Paestum,

of the city of Elia (modern Velia). It was the home of Parmenides and

Zeno and was founded in the 5th century b.c. by refugees from the Persian

invasions of eastern Greece of that epoch. Take the autostrada for Reggio

Calabria, exit at Battipaglia and head towards Omegliano Scalo. Ask

for the "scavi di Velia". In nearby Ascea, there is even a hotel

called Magna Grecia! Is nothing sacred?

Greeks

in Naples

Considering

the Greek history of Naples, it isn't surprising that one should find

considerable amounts of Greek masonry beneath the city and in the outlying

areas. It is, however, the little bits and pieces of "mental masonry"

--less tangible fragments of Greekness in the history and customs of

Naples-- that fascinate the most. One such item, for example, is the

simple fact that after the fall of the Roman Empire, under Justinian's

brief unification of the eastern and western empires, Greek was again

the language of Naples. A thousand years after it first reached these

shores, Greek was for a brief time once again the language of official

commerce, politics and religion. Considering

the Greek history of Naples, it isn't surprising that one should find

considerable amounts of Greek masonry beneath the city and in the outlying

areas. It is, however, the little bits and pieces of "mental masonry"

--less tangible fragments of Greekness in the history and customs of

Naples-- that fascinate the most. One such item, for example, is the

simple fact that after the fall of the Roman Empire, under Justinian's

brief unification of the eastern and western empires, Greek was again

the language of Naples. A thousand years after it first reached these

shores, Greek was for a brief time once again the language of official

commerce, politics and religion.

That last

item, religion, has perhaps to do with another piece of Greekness still

left in the city. The long history of the Greek Orthodox Church in Naples and southern Italy,

in general, has begotten the curious tradition of otherwise typical

Roman Catholics calling upon the services of a Greek Orthodox priest

to perform ritual blessings of newly built houses and even to ward off

the "evil eye".

I know,

personally, of two such cases. A friend of mine moved into a new house

and simply called up the priest from the one Greek Orthodox church in

Naples to come over and bless the place. Also, a woman I know was a

librarian at one of the many university libraries in town. Books were

disappearing. Whether that was due to simple mundane larceny or otherworldly

book-fairies was irrelevant. She called the same church and got a young

priest to come over and bless the library. Interestingly, he was aware

of the custom, yet guarded in his willingness to muscle in on Roman

Catholic turf. Nevertheless, he did as requested.

My friend's

house is doing fine, but I never found out if the books were returned

or, at least, stopped disappearing. That, of course, is not the point.

In both cases, my friends simply shrugged off my "But-you're-a-Catholic"

challenge. Everyone knows the Greeks have "something special".

soccer

(1)

Italian

professional soccer is built along the principles of one major league,

the A league; then, a minor league, the B league; then, the very minor

leagues, the C1 and C2 league. Each league has 18 teams; at the end

of each season, the last 4 teams in the A league are "sent down" to

the B league, and the top four in the B league move up. Similarly, the

bottom four in the B league exchange places with the top four in the

C1 league, and so forth with C2. In theory, then, even a small-town

team can win its up from the bottom of the minors through the B league

and into the A league, where it, too, has a shot at the national title.

That seldom happens, but the hope of being just such a "Cinderella"

team keeps soccer in small towns going. Conversely, a big-city, once

high-and-mighty team such as Naples can lose its way down and out of

the A league and into the B league. That happened in the late

1990s to Naples. They struggled back up to the A league for a season

and then went down again to the B league. Italian

professional soccer is built along the principles of one major league,

the A league; then, a minor league, the B league; then, the very minor

leagues, the C1 and C2 league. Each league has 18 teams; at the end

of each season, the last 4 teams in the A league are "sent down" to

the B league, and the top four in the B league move up. Similarly, the

bottom four in the B league exchange places with the top four in the

C1 league, and so forth with C2. In theory, then, even a small-town

team can win its up from the bottom of the minors through the B league

and into the A league, where it, too, has a shot at the national title.

That seldom happens, but the hope of being just such a "Cinderella"

team keeps soccer in small towns going. Conversely, a big-city, once

high-and-mighty team such as Naples can lose its way down and out of

the A league and into the B league. That happened in the late

1990s to Naples. They struggled back up to the A league for a season

and then went down again to the B league.

The salad

days of Neapolitan soccer were in the 1980s and early 90s, a period

in which Argentine superstar, Diego Maradona, led Naples to two national

championships. In those days, streets on a Sunday afternoon after a

homegame were either full of flag-waving, horn-tooting celebrations

of victory or glum fans wandering slowly home, wondering just what had

gone wrong. Fan involvement was intense.

Things

have gone very wrong in the last few years, and any sort of soccer emotion

at all is noticeably absent. There are few victories to speak of, and

no one seems to care about the defeats. Only a few thousand diehard

fans even bothered to show up at the giant San Paolo stadium yesterday

to watch Naples play Lecce. It was just as well --it was 1-1 tie. That

draw added one measly point to Naples' total in the league standings

(a victory counts 3 points) and left them still mired fourth from the

bottom in what is called the "demotion zone". BUT -- it is the demotion

zone of the B league! Naples is at the gates of true soccer obscurity

-- the C league, as minor as you can get in Italian professional soccer.

If Naples

goes down to the C league, it will be the first time that has happened

since the league system was set up in its current form back in the 1920s.

This morning at the local coffee-bar, cynics were joking about being

in the C league next season, where they might be able to win a game

or two—maybe against that powerhouse team from the island of Ischia.

They can play on the beach where the few remaining fans will be able

to watch in comfort from the roadside.

They certainly

won't need the San Paolo stadium in Fuorigrotta (photo, above).

De

Simone, Roberto

Neapolitan

musicologist Roberto De Simone is a most remarkable person. He was the

artistic director of the San Carlo Theater in the late 1980s and was

appointed director of the Naples Conservatory in 1995. He has spent

his professional life rejuvenating the cultural history of his city.

This includes collecting folk tales and music, and reviving a number

of seldom- or never-performed pieces from the vast repertoire of 18th-century

Neapolitan comic opera— works by Pergolesi

and Jomelli, among others. Neapolitan

musicologist Roberto De Simone is a most remarkable person. He was the

artistic director of the San Carlo Theater in the late 1980s and was

appointed director of the Naples Conservatory in 1995. He has spent

his professional life rejuvenating the cultural history of his city.

This includes collecting folk tales and music, and reviving a number

of seldom- or never-performed pieces from the vast repertoire of 18th-century

Neapolitan comic opera— works by Pergolesi

and Jomelli, among others.

He has

written, among much other work, a requiem in memory of the poet Pier

Paolo Pasolini, a cantata for the 17th-century Neapolitan revolutionary,

Masaniello, and, in 1999, a remarkable

oratorio, "Eleonora," in honor of the

republican heroine of the Neapolitan revolution of 1799. He is currently

reworking his stage version of The Cat Cinderella, based on the

oldest version of that fairy-tale, a dialect tale by Giambattista Basile from the early 1600s. As with

many of his other works, he will take the show on the road in a version

that employs a modified Neapolitan dialect in order to make the work

accessible to a wider audience.

Copyright

(2)

Massimiliano

Amatrice is risking a lawsuit, but the publicity is probably worth it.

He has opened a hole-in-wall, stand-up or take-out fast-food place near

Piazza del Gesù in the heart of downtown Naples. His advertising

logo, displayed prominently over the entrance, is a large red letter

M, clearly meant to remind you of McDonald's. Below the M is the word

Maren's -- an English-looking play on the Neapolitan word for

snack, "marenna", itself a variation of the Italian "merenda". The M

also stands for "mamma"—mother—says the proprietor, a reminder

that he prepares snacks just like mother used to make. Indeed, there

are no fast-food burgers here --just typical and tradtional Neapolitan

fare: small pizzas, enormous sandwiches with ham and mozzarella, rice

balls, etc. Massimiliano

Amatrice is risking a lawsuit, but the publicity is probably worth it.

He has opened a hole-in-wall, stand-up or take-out fast-food place near

Piazza del Gesù in the heart of downtown Naples. His advertising

logo, displayed prominently over the entrance, is a large red letter

M, clearly meant to remind you of McDonald's. Below the M is the word

Maren's -- an English-looking play on the Neapolitan word for

snack, "marenna", itself a variation of the Italian "merenda". The M

also stands for "mamma"—mother—says the proprietor, a reminder

that he prepares snacks just like mother used to make. Indeed, there

are no fast-food burgers here --just typical and tradtional Neapolitan

fare: small pizzas, enormous sandwiches with ham and mozzarella, rice

balls, etc.

The large

letter actually reminds you more of the Metropolitana logo common throughout

Europe and unless McDonald's wants to make a case that they own part

of the alphabet and wants to sue most of the subway lines on the continent,

this may wind up in the same category as the time Warner Bros. threatened

Groucho Marx with a lawsuit over the title of a Marx Brothers film,

A Night in Casablanca, so close on the heels of the Warner Bros.

film, Casablanca. Groucho reminded the studio that he and

his brothers had been brothers for longer than the Warner Bros.

had been brothers, and that he was seriously considering a countersuit

over that. The studio let it drop. Come to think of it, there was a

great 1931 German movie called "M" starring Peter Lorre as a psychopathic

child-molester/murderer. It was directed by Fritz Lang. Can he sue somebody?

|