©

2004 Jeff Matthews & napoli.com

Haunted

houses

Speaking of places in Naples—yesterday's reference

to Gaiola—that are said to be haunted, there are at least two

so-called "haunted houses" in the city, buildings where terrible things

are known to have happened, and, no doubt, other terrible things that

are said to have happened never did but probably will if you get too

close. Speaking of places in Naples—yesterday's reference

to Gaiola—that are said to be haunted, there are at least two

so-called "haunted houses" in the city, buildings where terrible things

are known to have happened, and, no doubt, other terrible things that

are said to have happened never did but probably will if you get too

close.

One is

at via Tasso 615 (photo, left), at the very top of the hill (about

500 feet above sea-level) where that road then swings left out to the

long drive along the Posillipo ridge or turns right for the main road

into the Vomero section of Naples. According to a sign near the high

metal scroll gate, the building is called the Corte dei Leoni ("Court

of the Lions"). The villa is about as set–off as it could be in

an overbuilt city; that is, though one side of the villa is across the

street from the standard markets and cracker-box buildings of the 1950s,

the other side is right at the top of a steep slope with nothing in

the way to obstruct a spectacular view of Vesuvius and the Bay of Naples.

The Corte

dei Leoni is not typical architecture for Naples. It is a three-story,

irregular but roughly rectangular pseudo-Renaissance building. It has

the arched windows with prominent keystones and columns on either side,

and a pale-red brick façade with enough protruding bricks to

give it a softened ashlar effect. Placed high up on the façade

in various places are a few graven symbols. Two that stand out are on

either side of a large window. They appear to be some version or other

of the winged caduceus, the staff carried in Roman mythology by Mercury.

The wings are there, to be sure, but on top of each staff is a stylized

horse's—or dragon's—head. They face inward and "look at"

each other across the arch of the window.

The roof,

in Renaissance fashion, slopes gently down to all sides. As the villa

is actually built on a slope, that part of the building that faces the

sea has an additional story using the extra space provided by the rapid

change in elevation from the front of the property to the back. There

is dark or stained glass in most of the windows. On the seaward side,

there is a remarkable spiral stairway that winds the height of the building;

it is on the inside, but encased in glass and very visible from the

outside. The entire property is protected from the street by a high

iron fence webbed with ivy, such that it is impossible to look into

the grounds. There is a stone plaque embedded in the façade that

reads 1922 in Roman numerals, but the stone is weathered enough to look

much older than that. On the sea-side there is also a balcony. The whole

effect is Renaissance, yes, but so foreboding that if Juliet, herself,

were to walk out on that balcony and call down to me, "What satisfaction

canst thou have tonight?" I would leave.

The only

other information provided by a small notice board near the gate is

that the premises are available for wedding receptions, banquets—that

sort of thing. I don't think they get many takers, because everyone

in Naples "knows" it is haunted. I have been unable to trace the source

of the superstition. The one terrible thing that has happened there

in my memory was just a few years ago. A woman was walking by the house

early on a Sunday morning. Except for her, the street was apparently

deserted, for there were no eye–witnesses. The scene, itself,

provided the details: there is a large tree on the grounds and, as she

walked by, a high branch hanging over the fence and above the street

chose that moment to snap and fall, striking the woman in the head and

killing her. That sent "I-told-you-so" headlines shivvering across the

newspapers for a few day.

The other

"haunted" building is the Palazzo of the Prince of Sansevero located

at Piazza San Domenico Maggiore. (You can read about that building

by clicking here and about the

Prince of Sansevero, renowned as a sorcerer, by clicking here.)

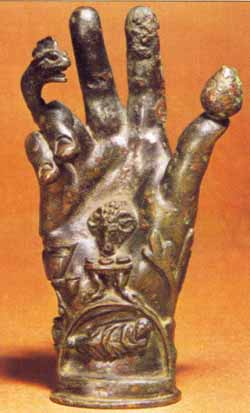

Gestures,

hand (3); luck (good & bad) (2)

I

once spilled wine on a woman seated next to me at a dinner in Naples.

I apologized—and she laughed and thanked me! I later found out

that spilling wine on people is said to bring good fortune. I subsequently

went on a major campaign to spill as much wine as possible on as many

beautiful women as possible, all the while wondering why I was never

really “getting lucky”. It turns out that the good luck

accrues to the spill-EE, not the spill-ER. Tricky business, this luck

stuff. I

once spilled wine on a woman seated next to me at a dinner in Naples.

I apologized—and she laughed and thanked me! I later found out

that spilling wine on people is said to bring good fortune. I subsequently

went on a major campaign to spill as much wine as possible on as many

beautiful women as possible, all the while wondering why I was never

really “getting lucky”. It turns out that the good luck

accrues to the spill-EE, not the spill-ER. Tricky business, this luck

stuff.

Predicting

your fortune from wine—or oenomancy, as it is known to

real winos—has a long history. Even way back in the caves, you

know, you spilled a little vino on your loin cloth and, hey, don't worry

about it— "spilling wine brings good luck," they would say. Maybe

a little symbolism in there: grapes, liquid, harvest, fertility. Besides,

homo sapiens fermantatis had good reason to spill wine. He was

drunk. I don't understand it, but I respect it. I mean, if you can paint

those beautiful bison on limestone walls at Lascaux, you were obviously

assembled correctly.

In Naples,

there is also a well–known gesture to keep bad luck away: the

sign of the "corna"—the horns, made with the extended index

and little finger and waggling that sign towards the ground (as if you

were rooting for the U. of Texas upside–down). This will ward

off the Evil Eye. Also, touching the hump of a male hunchback is good

luck. Now, if you tell me all that, I may not agree with what you say,

but until the going gets rough I'll defend your right to say it. It

has just that plausible mixture of the Primeval and the Light vs Dark—what

my fruit vendor has termed "the Manichaean dichotomy, the Antinomial

on the brink of the abyss." (This could be what has been wrong with

his nectarines, lately, too). But it might be true. And as Pascal wagered

(roughly, but really): "Gee, you never can tell, so you might as well

believe." Is that gutsy, or what? Thus Spake Zaramilquetoast.

But the

one thing that tells me just how lucky I am and am ever going to remain

if I keep living on my street is this: If you step in dog-poop, Neapolitans

will tell you, "Don't worry. It brings good luck." That's right—Stepping…in…feces…brings…

good… luck! (I know this is delicate, so you may wish to go

read something about the history of the Khmer Rouge.)

I've heard

of Easy Street, the Street of Dreams, and The Street Where You Live,

but if this morsel of folk wisdom is true, then in terms of the ability

to confer happiness, all of these thoroughfares are squalid back-alleys

and blighted dead-ends compared to My Street. If stepping in the Sirius

Stuff is lucky, then My Street is an eight–lane toll–free

Expressway to human felicity.

The Voo–doo

Doo–doo Institute for Demographic Studies has shown that residents

of My Street have a higher income, live three–and–one–half

years longer than the national average, and are very noisy. Research,

however, has not shed any light on the origins of the belief that any

of this has to do with you know what. Sceptics, of course, claim that

attributing good fortune to conditions over which one has no control

is understandable, a kind of safety valve for the psyche, a de-stressing

little smile in the face of the great Existential Maw which sooner or

later devours us all. This, of course, is ludicrous and maybe even wrong.

It's the doggie-doo that does it.

Some time

ago, the City Parenting Persons put a Curb Your Dog sand-box down at

the corner on My Street. Man's Best Friend, of course, wouldn't go near

it. Nosiree, Spot. You stop leaving little patties of good luck—those

pulchritudinous tugboat-sized fortune cookies—in the right places

and pretty soon you're getting kicked around and blamed for broken

legs and missed lottery numbers. No way. I may be a damned dog, but

I ain't that dumb.

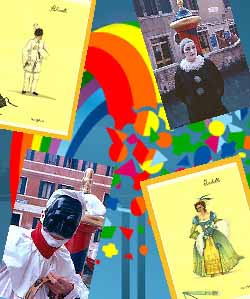

Carnevale

(1)

Today

is Mardi Gras. I was made aware of that yesterday when I noticed a couple

of very young children parading around in pirate costumes in the middle

of Piazza Plebiscito yesterday. It is

strange that in a city that has taken to foreign celebrations such as

Halloween, they don't go in much for a traditional Catholic holiday,

here. (There are, however, smaller towns near Naples that have traditional

festivities for carnevale, such as Avellino and Capua.) Today

is Mardi Gras. I was made aware of that yesterday when I noticed a couple

of very young children parading around in pirate costumes in the middle

of Piazza Plebiscito yesterday. It is

strange that in a city that has taken to foreign celebrations such as

Halloween, they don't go in much for a traditional Catholic holiday,

here. (There are, however, smaller towns near Naples that have traditional

festivities for carnevale, such as Avellino and Capua.)

The only

two cities in Italy with extravagant Rio–or New Orleans–like

activities for carnevale are Viareggio—on the western coast

of Italy as you move up the Ligurian coast past Livorno (quaintly known

in English as "Leghorn") on the way to Genoa—and, of course, Venice.

The only festival of that nature in Naples, I think, is the Festival

of Piedigrotta on Sept. 8 and 9. I say is, though used to be would be

more like it. I don't recall ever seeing anything more than a perfunctory

fireworks display, a far cry from the mile-long parade of floats, bands

and outlandish bedizenment wending its way along the seaside public

gardens to the Church of Piedigrotta years—decades—ago.

The city keeps promising to revive it. Who knows. So, today, there were

a few city-sponsored festivities around town, but nothing much.

My single

experience with the Carnival of Venice (besides listening to Rafael

Mendez' splendid trumpet solo on the piece of the same name!) was a

number of years ago. It was freezing and there was much too much over–amplified

music pumped into the crowd by crazed DJs from a local Rock station.

A friend wanted to go and visit the tomb of Igor Stravinsky located

on the cemetery island of San Michele in the lagoon. There, while he

was moping over the tomb of the maestro, I walked around and found a

remarkable inscription on a tomb from 1888, which said, in essence,

this:

| Rest

in Peace, my Little Boy

We

wished for you intensely, my beloved Nina and I. We had no son,

but you were born lifeless, and your dear mother died, as well,

giving birth to you, leaving me with five tender little girls.

|

I remember

being struck by the enormity of it: this poor women had died trying

to make up for her "failures" in producing nothing but girls. Her husband

just had to have a son.

It also

reminded me of when I got married and moved to Naples. A young woman

from a small town near Naples found out I was newly wed and said to

me, "auguri e figli maschi"—"best wishes and male children". She

was sincere, but it was one of those phrases that is well-rehearsed

through practice, the traditional thing to say to newly-weds. Today,

it has an olden ring to it, or at least it embodies the values of small

southern towns, one of which values is (or was) the large family—preferably

with a lot of strong male hands for farming. Having said that, it seems

to me that whenever I pass through one of those places, I see an awful

lot of women out working in the fields, or balancing heavy bundles on

their heads as they walk along the roadside, or leading animals to pasture,

so I'm not sure what all those strong male hands actually do. Maybe

they're for wielding the traditional lupara—shotgun—though,

again, I imagine women can be pretty good at that, too.

Young,

Lamont (2)

Lamont

Young's "castle" is going to be restored. It is a quaint piece of Victorian

Gothic architecture set on the cliff of Pizzofalcone, the original

cliff of Naples that overlooks the Castel dell'Ovo and the small harbor of Santa Lucia.

When it was built in the early years of the 20th–century, it really

did overlook all that; however, subsequent construction along the seaside

road over the course of the rest of the century has led to the pitiful

sight of a "castle" from which there is with no view at all except of

the splendid backs of the 4–and–5–star hotels now

directly in front of—and considerably higher than—the

cliff. Lamont

Young's "castle" is going to be restored. It is a quaint piece of Victorian

Gothic architecture set on the cliff of Pizzofalcone, the original

cliff of Naples that overlooks the Castel dell'Ovo and the small harbor of Santa Lucia.

When it was built in the early years of the 20th–century, it really

did overlook all that; however, subsequent construction along the seaside

road over the course of the rest of the century has led to the pitiful

sight of a "castle" from which there is with no view at all except of

the splendid backs of the 4–and–5–star hotels now

directly in front of—and considerably higher than—the

cliff.

The castle

was one of three or four such buildings put up by Young along the same

unusual lines, highly criticized at the time as being not in keeping

with the traditions of Neapolitan architecture. One of Young's other

castle-like Victorian Gothic structures in another part of town even

features an artificial crack (photo) high up on one of the towers, meant

to simulate great age or, perhaps, a lightning strike. All of these

buildings would be at home on the covers of gloomy novels about moors,

fog and frail heroines.

The buildings

are, however, charming, and the one on Pizzofalcone is now going to

get one–and–a–half–million euros to undo the

damage down by arson a few years ago; in addition, part of the grounds

will be converted to a museum/exposition room that will inform visitors

about this fascinating Neapolitan with the very English name. Here they

will learn about Young's plan for the total rebuilding of the city (including

the construction of an underground train line!) in the 1890s (a plan

that lost out to the Risanamento—the gutting of large sections

of the city).

[See

here for more on the life and work of Lamont Young.]

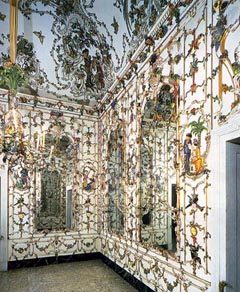

Portici

| This

ornate porcellan drawing room was designed by Giuseppe and Stefano

Gricci and Luigi Restile. It was completed in 1757 within the Royal

Palace at Portici. It was transferred to the National Galleries

at Capodimonte in 1866. There is a separate item on Capodimonte

here. |

I

remember sailin across the Bay of Naples many years ago and noticing

a broad swath of green on the south slope of Vesuvius. This wooded area

spread inland almost from the sea to a spot a good distance up the slope

and was separated at the midpoint by a building so large that some of

the details of the architecture stood out even to an observer out at

sea. The greenery lay isolated in the midst of what is now the most

densely populated area in western Europe, surrounded on both sides by

chaotic urban sprawl. I

remember sailin across the Bay of Naples many years ago and noticing

a broad swath of green on the south slope of Vesuvius. This wooded area

spread inland almost from the sea to a spot a good distance up the slope

and was separated at the midpoint by a building so large that some of

the details of the architecture stood out even to an observer out at

sea. The greenery lay isolated in the midst of what is now the most

densely populated area in western Europe, surrounded on both sides by

chaotic urban sprawl.

Subsequently

I learned that the property was the old Bourbon Royal Palace and grounds

at Portici, built in the 1730s and 40s at the behest of Charles III, recently arrived from Spain to run the

newly independent Kingdom of Naples. It is one of four Bourbon Palaces,

all from roughly the same period. The other three are the Royal

Palace in downtown Naples, the Palace on the Capodimonte

hill, and the great Palace in Caserta, the so-called "Versailles of

Italy". In the course of more than two centuries, the Palace at Portici

has served, obviously, as a royal residence, but also as an archaeological

museum for artefacts from nearby Pompei and Herculaneum. Also, in 1839,

it had the distinction of being one terminus of Italy's first railway,

a track that started in town and wended its way out to Portici largely

for the purposes of making it easier for the royal family to "get away

from it all".

For most

of the 20th–century, the premises housed the Agricultural Department

of the University of Naples, which accounts for the abundance of the

greenery I noticed from a distance. There is a wide variety of vegetation

on the grounds, much of it from elsewhere in the world, all neatly labelled

and available for study. The Palace, itself, is remarkable. I was there

in the 1980s when they tore up some of the flooring to inspect the integrity

of the large tree-trunks that served as beams that cross-braced the

entire building and held the floors in place. After two centuries, they

were still solid and very little of the structure had to be reinforced.

(Given the denuded look of the area after centuries of chopping down

trees, I found it hard to believe—and I still find it hard to

believe—that those tree trunks originally came from around here,

but that's what they tell me.)

There is

now a plan to move the Agricultural Department out of the Palace to

another facility nearby and to convert the Palace to a museum focusing

on the archaeological and geological features of the area, which are

considerable: Pompei, Herculaneum, and Mt. Vesuvius. The university

will still have access to some of the building for classes and, of course,

will continue to use the large garden—a forest, really. The 20

million euros allocated for the restoration will go into removing the

signs of decades of use by the university, including chemical traces

from laboratories; then, the trappings and furnishings of the original

18th–century building will be restored. The project is expected

to take three years.

Troisi,

Massimo

I

suppose it is futile—but understandable—to speculate how

the career might have turned out of one who died much too young. The

Neapolitan papers this week spent some time doing that, true, but, generally,

just paid heartfelt tribute to Massimo Troisi, from San Giorgio (near

Naples), who died in 1994 but who, this week, would have turned 50. I

suppose it is futile—but understandable—to speculate how

the career might have turned out of one who died much too young. The

Neapolitan papers this week spent some time doing that, true, but, generally,

just paid heartfelt tribute to Massimo Troisi, from San Giorgio (near

Naples), who died in 1994 but who, this week, would have turned 50.

Troisi

made his first film, in 1981, Ricominciamo da tre (a pun on the

expression Ricominciamo da zero—Let's Begin at Zero (the

beginning)—thus, Let's Start at Three, and his last film, shortly

before his death, Il Postino (The Postman—probably his

best-known film abroad). Perhaps only Roberto Benigni, among recent

Italian comics, strikes you the same way Troisi does—as having

that quality of comic genius worthy of mentioning in the same breath

as the great Totò. (Benigni and Troisi appear in one film

together, in 1984: Non ci resta che piangere (There's nothing

left to do but cry) where they are transported in time back to the 1400s

and even meet Leonardo da Vinci and give him some pointers.)

Troisi

already generates the same type of "Do you remember that episode…?"–stories

that characterize conversations about all great comics. (Do you remember

that scene of Laurel and Hardy moving the piano up the long flight of

steps? Of course you do.) There are scores of those about Totò

and, by now, a lot of them about Troisi. Yes, I remember that scene

where Troisi plays the wrong Mary (!), not the mother of Jesus,

but another Mary in "a city of Galilee named Nazareth" whose daily routine

gets interrupted by an inept Herald Angel who keeps barging onto the

stage with "Hearken! Mary…the Lord is with thee…thou shalt

conceive…" Troisi spends the skit trying to convince the angel

that he has come to the wrong house and the wrong Mary. Joseph's wife

is over on the next street. There is not the least sense of irreverence

in the performance, either, and I am sure the Pope thinks it's a riot!

Troisi's

language was that of Naples, with virtually no attempt to modify his

difficult native dialect to a more standard Italian for the benefit

of those who might have difficulty understanding him—audiences

in northern Italy, for example. With Totò, Troisi is a living

language lesson and one more reason why almost all Italians now like

to think they speak a little Neapolitan.

Ischia

A

Donkey Serenade

Being a Recounting of Marvelous and Intrepid Adventures on Remotest

Ischia.

We all have shreds of strangeness scattered through

our lives, giving a special dreamlike quality to the most fortunate

of our memories. One of mine was discovering Antonio Gaudi, the magical

Catalonian architect, whose cathedral stands in Barcelona—a psychedelic

stalagmite of parabolas, saddle-like curves and weird geometries from

another dimension dripping down like wet sand through the fingers of

a playful giant. We all have shreds of strangeness scattered through

our lives, giving a special dreamlike quality to the most fortunate

of our memories. One of mine was discovering Antonio Gaudi, the magical

Catalonian architect, whose cathedral stands in Barcelona—a psychedelic

stalagmite of parabolas, saddle-like curves and weird geometries from

another dimension dripping down like wet sand through the fingers of

a playful giant.

I added

another tatter a few weeks ago on Ischia. I had just finished ploughing

through an imposing German tome on the island. It was full of footnotes

and umlauts. In fact, you are almost reading about the late Stone Age,

the Bronze Age, Pithecusa (the original Greek name for the island) and

how the Greeks found in Ischia's Mt. Epomeo another Olympus, another

safe hiding place for their Gods. Then came the Romans, the Paleochristians,

the Aragonese and the Saracens. So, be glad I found Viola, a lovely

brown donkey mare, who took me up the slopes of Epomeo, where the spirit

of Gaudi dwells.

After making

the long storm-tossed crossing from Neapolis and quelling a native uprising

at my hotel, I betook me to the quaint outpost of Fontana, the most

convenient "base camp" from whence to begin the climb up the 800-meter

high mountain. It was then that I saw Viola—beautiful brown eyes,

long lashes, even longer ears, and a mane stroked by, alas, who knows

how many coarse hands. She was standing in the main square in Fontana,

reluctantly looking for passengers. She looked like Rocinante hoping

against hope that Don Quixote had wandered away and would never come

back.

"Oh, a

donkey," I exclaimed, a veritable Julian Huxley finally seeing his way

through to some great biological truth.

"You are,

indeed, most perceptive, bwana-sahib," croaked the wizened Chargé

du Donkeé. He genuflected in the traditional fashion of his ancestors,

touching first his forehead, then his heart, then my wallet. "She will

take you right to the top for a mere trifle."

"Hmmm,

that's not even a pittance a pound. Not bad. But, am I not too stout—all

solid muscle, of course—but a bit too hefty for this delicate

steed?"

"Not to

worry, O wise one, for it is written that this is the life they are

born to."

Viola,

naturally, had heard this Bible-thumping, fundamentalist interpretation

of Genesis 1:26 many times before and she was not amused. But, with

that floppy-lipped snort that donkeys emit when they dream of their

great stallion cousins flashing like Pegasus free and unshod across

Arabian dunes, she acquiesced. I climbed aboard and we went straight

up, first on a paved road and then the last two-hundred yards or so

along a precise trail, partially hewn out of the rock, but mostly just

plain worn down by the methodical sculpting of countless plodding hooves.

The summit

of Epomeo is a castle carved out of rock. There is no building; all

the chambers in the one-time home to an order of Franciscan monks are

in the rock. Again, Gaudi's giant friend must have poked his fingers

into the lava when it was still warm and pliant, yet firm enough to

hold impressions which an age later would become the chapel, dining

hall and cells for the monastery of San Nicola.

If you

go when there is a mist blowing up the slopes, the jagged rock that

forms a watchtower on the summit tears at the stream of whiteness swirling

by. It sticks up like a cockeyed crown on a ghostly head calling you

into a fairy-tale, and if you are in the fanciful mood that accepts

fairy-tales, then that will be your "strange" moment, the one you remember.

That and

the sunrise, because sadly for the monks but happily for you, this mountain

retreat is now an inn. You can ride or walk up in the evening and stay

in one of the cells. (It's not as bleak as it sounds; each cell

has a balcony with a breathtaking view, the beds are clean, and when

you run out of gruel, you can go to the restaurant). From the watchtower

and various points around the summit, there is a stunning view straight

out over the island and the gulf to Vesuvius and the Sorrentine Peninsula.

Here, it is pardonable to believe in the illusory astronomy that the

Earth is the center of all things, as the sun paces the passage of eternity,

slowly shifting, sunrise by sunrise, inexorably along the rim

of the mountains and back again. On Ischia, "to watch the dawn from

Epomeo" is a metaphor of splendour—to be up there in monastic

stillness watching the sun perform its timeless rites and to feel that

you are the first ever to behold the transformation of night into day.

"Neptune"

fountain

I have difficulty believing that they are going to move

"Neptune" again. I was down there today looking at it, and in my non-expert

opinion of where fountains belong and how they fit in and why they should

not be disassembled, moved and put back together every few years, it

looks fine. True, they pinched off one traffic lane a bit in order to

install the fountain, but they opened up the pedestrian area around

the immediate area, and have put in benches and a tourist information

bulletin board. The fountain is now on via Medina, adjacent to Piazza

Municipio. I have difficulty believing that they are going to move

"Neptune" again. I was down there today looking at it, and in my non-expert

opinion of where fountains belong and how they fit in and why they should

not be disassembled, moved and put back together every few years, it

looks fine. True, they pinched off one traffic lane a bit in order to

install the fountain, but they opened up the pedestrian area around

the immediate area, and have put in benches and a tourist information

bulletin board. The fountain is now on via Medina, adjacent to Piazza

Municipio.

There are

very few pieces of sculpture that have traveled as much as this one.

This fountain started out down by the Arsenal --at the port-- when it

was built in the 1500s. It was built on the order of Enrico de Guzman,

the Spanish viceroy at the time and was situated so that it faced his

residence. The design is by Giovanni da Nola; Neptune (the centerpiece)

and the two satyrs are by Pietro Bernini.

In 1629,

it was moved up to Largo Palazzo, now called Piazza Plebiscito on the order of the viceroy, Alvarez

de Toledo. Then, in 1634, it was moved down to the sea at Santa Lucia

after being touched up by Cosima Fanzago. There, it was in such danger

of being exposed to artillery fire that it was moved up to via Medina,

more or less where it is today. In 1647 it was repaired after being

damaged in the uprisings of that year; bits and pieces taken away

as souvenirs to Spain by the viceroy also had to be redone. In 1659,

it was moved again, this time to Calata San Marco, about two

blocks from its current location. In 1700 it was moved back to via Medina

to be nearer to the main road leading down to the port. At that time,

sea horses and tritons were added to the statue. In 1898 it was moved

to Piazza Borsa (the Stock Exchange) and, thus, was located at

the beginning of Corso Umberto, the broad boulevard leading to the main train station.

That square is currently the site of construction for the new Naples

Metro underground train line, so in 2001 the statue was moved back to

via Medina where it was in 1640.

The statue's

current location is described as "temporary," and it is to be returned

to Piazza Borsa when they finish the metro station in that square.

I hope they leave it where it is.

Carnevale

(2)

I

see in the papers that 55.000 people have showed up in Venice

for the beginning of carnevale, a celebration that will run through

next Tuesday, Mardi Gras. I

see in the papers that 55.000 people have showed up in Venice

for the beginning of carnevale, a celebration that will run through

next Tuesday, Mardi Gras.

How can

this be?—I ask myself. Did I not identify last Tuesday, Febraury

18, as Mardi Gras on the basis of seeing two young children parading

around in pirate costumes? Indeed. There must be some mistake. Perhaps

I was thinking in a different calendar. The Coptic Christian calendar,

perhaps? That might be a way out, I think. I don't know, however, that

there are many Copts in Naples. On the other hand, I do often walk by

a small private club called the "Circolo Mare Rosso" (The Red

Sea Club). Beneath that inscription is the equivalent name, written

in a very strange alphabet that seems to be full of pitchforks and dyslexic

versions of the letter J. Yes! That must be Coptic, the end-stage of

ancient Egyptian, and now the liturgical language of a strong minority

of Christians in Egypt, an overwhelmingly Moslem nation. I have somehow—just

by walking by the place—picked up on their early celebration of

the week before the beginning of Lent. I rush down to check it out.

Oops. The sign proves to be in the Amharic language, written in what

is called Ethiopian script, a derivation of the old Arabic alphabet.

It really looks nothing like the Coptic script, I have to admit.

Hmmm. Maybe

I was thinking in the Neapolitan Revolutionary calendar, from way back

in 1799 when Neapolitan revolutionaries redid the entire calendar

after the fashion of Revolutionary France: January was called "Rainy".

I think February was called "Foggy". I am not sure of that one, but

the potential for confusion with the Seven Dwarfs is obvious and certainly

could have been no source of strength to the Republic. Besides, they

were anti-clerical, so I don't suppose reactionary Christian holidays

were even recognized in the calendar. That, too, is out.

It can't

be the Greek Orthodox calendar, because I don't know anything about

that one, except that it uses the Julian Calendar instead of the

Gregorian Calendar to calculate Easter, and, after dividing the vernal

equinox by pi, they are bound to be a week or two off, just like me.

I may just have to step up and forthrightly take responsibility for

myself and blame my miscalculation all on those little Revolutionary

Orthodox Coptic kids running around Piazza Plebiscito last week.

[In spite

of all that, the Greek Orthodox faith has an interesting history in

Naples. Click here.]

Mercato,

Piazza (1); City walls;

Carmine church and castle; Porta Capuana

If by "city

walls" you mean the ancient Greek or Roman ones that surrounded Neapolis,

there is nothing left of those above ground in modern Naples. There

are, however, some fragments that have been excavated and left open

for viewing; the most prominent one is the section of the Greek wall

visible at Piazza Bellini. The rest has

disappeared under—in some cases—natural catastrophe, such

as mudslides (a prominent one occurred in the sixth century), or was

simply torn down or built over in the typically palimpsest approach

to urban planning that has characterized Naples in its long history.

The medieval

walls are a different story. Starting with the Angevins in the 14th–century

and continuing well into the Spanish and even Bourbon periods in Naples,

the protective wall around Naples was constantly under some phase of

construction and renewal. It is in the late 19th– and early 20th–century,

during the great Risanamento—the

urban renewal—of the city, that that changed. Massive portions

of the medieval walls were torn down; yet, some were left standing as

historical markers, and segments of the wall were simply incorporated

into modern buildings.

The most obvious historical marker is the part of wall

and the pillars at what used to be the south-east corner of the city

wall across from Piazza Mercato and the Church of the Carmine

(see below). There is not much left of this castle, and the ruins

you see here are often referred to simply as "part of the old wall down

by the port". In reality, this is what remains of the Castello del

Carmine, now on the main road that runs east along the industrial

port of Naples. It was built by the Angevin ruler, Charles III

of Durazzo, in the 1380s. It was a true fortress and at the center of

battles during the Angevin and subsequent Aragonese

period. It was expanded, as well, under the Spanish in the 1560s. It

was also one of the strongholds of conspirators during Masaniello's

revolt, which led to a very short-lived (5 days!) first "Neapolitan

Republic" in 1647. It played a strategic role, as well, in later military

campaigns, namely the Neapolitan revolution of 1799 and the Bourbon

resistance to the army of Garibaldi in 1860. The pillars seen in the photo

are all that remain of the Carmine Gate, one of the main entrances into

the city along the south wall in the late Middle Ages. The structure

was demolished in the early 20th century to make room for road expansion

along the port. The most obvious historical marker is the part of wall

and the pillars at what used to be the south-east corner of the city

wall across from Piazza Mercato and the Church of the Carmine

(see below). There is not much left of this castle, and the ruins

you see here are often referred to simply as "part of the old wall down

by the port". In reality, this is what remains of the Castello del

Carmine, now on the main road that runs east along the industrial

port of Naples. It was built by the Angevin ruler, Charles III

of Durazzo, in the 1380s. It was a true fortress and at the center of

battles during the Angevin and subsequent Aragonese

period. It was expanded, as well, under the Spanish in the 1560s. It

was also one of the strongholds of conspirators during Masaniello's

revolt, which led to a very short-lived (5 days!) first "Neapolitan

Republic" in 1647. It played a strategic role, as well, in later military

campaigns, namely the Neapolitan revolution of 1799 and the Bourbon

resistance to the army of Garibaldi in 1860. The pillars seen in the photo

are all that remain of the Carmine Gate, one of the main entrances into

the city along the south wall in the late Middle Ages. The structure

was demolished in the early 20th century to make room for road expansion

along the port.

Directly across the street is Church of Santa Maria

del Carmine (photo, left) at one end of Piazza Mercato (Market

Square), one of the most historic sites in Naples. The church itself

was founded in the 12th century by Carmelite monks driven from the Holy

Land in the Crusades. The historic name of Piazza Mercato is

Piazza Moricino. It was the site in 1268 of the execution of

Corradino, the last Hohenstaufen pretender to the throne of the kingdom

of Naple, at the hands of Charles I of Anjou, thus beginning the important

Angevin reign of the kingdom. In 1647 the square was also the site of

battles between rebels and royal troops during Masaniello's Revolt,

and in 1799 the scene of the mass execution of leaders of the Neapolitan

Republic. Directly across the street is Church of Santa Maria

del Carmine (photo, left) at one end of Piazza Mercato (Market

Square), one of the most historic sites in Naples. The church itself

was founded in the 12th century by Carmelite monks driven from the Holy

Land in the Crusades. The historic name of Piazza Mercato is

Piazza Moricino. It was the site in 1268 of the execution of

Corradino, the last Hohenstaufen pretender to the throne of the kingdom

of Naple, at the hands of Charles I of Anjou, thus beginning the important

Angevin reign of the kingdom. In 1647 the square was also the site of

battles between rebels and royal troops during Masaniello's Revolt,

and in 1799 the scene of the mass execution of leaders of the Neapolitan

Republic.

If

you walk north into the city from that point along what used to be the

line of the eastern wall of the medieval city, you will probably get

lost, but—after some judicious zigging and zagging—you will

eventually come to Porta Capuana and Castel Capuano (photo,

right) takes its name from the fact that it was at the point in the

city walls where the road led out to the city of Capua. The castle is

at the end of via dei Tribunali and today houses the Naples Hall of

Justice. It was built in the twelfth century by William I, the son of

Roger the Norman, the first monarch of the Kingdom

of Naples. It was expanded by the Holy Roman Emperor, Frederick

II of Swabia and became one of his royal palaces. Under the Spanish

viceroyship of Don Pedro de Toledo in the sixteenth century, it became

the Hall of Justice, the basements of which served as a prison. Over

the entrance to the castle you still see the crest of the Emperor Charles

V, who visited Naples in 1535. The castle has undergone many restorations,

one as recent as 1860, and thus no longer retains a great deal of its

original appearance.

Porta Capuana (photo, left), in spite of the name, is not the ancient

gateway to the decumanus maximus, the main east-west road that

once led out of Roman Naples to Capua. When the city was extended eastwards,

the construction of the new Aragonese city

walls meant relocating the original gate, which had been closer

to the castle. The present gate was built in 1484. It is still there and

you can drive or walk through and around it.

The most

interesting examples of how the medieval walls have simply been incorporated

into more modern buildings occur if you keep moving along that same

line of the eastern wall to the point where it turned left to run along

the northern side of medieval Naples, along what is now via Foria. At

that corner is an enormous building now housing municipal office space

but with the inscription Caserma [barracks] Garibaldi

still prominent on the façade. That ex-barracks was the medieval

monastery of San Giovanni a Carbonara, which, itself, was built using

the corner formed by the meeting of the eastern and northern walls of

the city as two sides of the monastery and then building the rest behind

that barrier.

As

you walk west along via Foria, keeping an eye on the dense row of buildings

that now stand where the wall used to be, the most obvious thing is

that modern office and apartment buildings are not only much higher

than the original wall, but that—in the case of one high school—

as high as the original height of the Greek city, itself. The city sloped

dramatically upwards in that direction. Piazza Cavour and the Archaeological Museum (down at the far end of the

wall before it turned to form another corner and run back towards the

sea) are below the highest point in the city, where the Greeks put their

acropolis. That height is no longer evident because of the modern buildings

in front of the ancient cliff. However, many of the buildings along

via Foria have used part of the medieval wall at their base. Why waste

a good 100 feet of solid wall? Put in a few windows and doors,

and you've got yourself the first few floors of one side of a building.

The San Gennaro Gate (photo, left), of course, is in that section of

wall and is not only still open, but is still a main pedestrian path

in and out of the old city. As

you walk west along via Foria, keeping an eye on the dense row of buildings

that now stand where the wall used to be, the most obvious thing is

that modern office and apartment buildings are not only much higher

than the original wall, but that—in the case of one high school—

as high as the original height of the Greek city, itself. The city sloped

dramatically upwards in that direction. Piazza Cavour and the Archaeological Museum (down at the far end of the

wall before it turned to form another corner and run back towards the

sea) are below the highest point in the city, where the Greeks put their

acropolis. That height is no longer evident because of the modern buildings

in front of the ancient cliff. However, many of the buildings along

via Foria have used part of the medieval wall at their base. Why waste

a good 100 feet of solid wall? Put in a few windows and doors,

and you've got yourself the first few floors of one side of a building.

The San Gennaro Gate (photo, left), of course, is in that section of

wall and is not only still open, but is still a main pedestrian path

in and out of the old city.

The medieval

western wall of the city—which, itself, followed the line of the

ancient Roman wall— was simply knocked down by the Spanish in

the 1500s when they decided to expand the city beyond the ancient confines

and move up the hill towards the Sant' Elmo Fortress. The long straight

road, via Toledo, laid by the Spanish in that period is well outside

the ancient city. The Spanish moved Port'Alba, originally one of the

main gates in the medieval western wall of the city, a few hundred yards

to the west (where it remains today), such that it opened onto the new

Spanish section of the city. By that time, the old west wall no longer

served any defensive purpose and much of it went the way of all old

walls in Naples—torn down, ploughed under, built over, and, in

some cases, reincarnated as parts of newer buildings.

Airports—

Yes,

this photo really was taken at Capodichino airport in Naples shortly

after the Germans left the city in 1943. Photo courtesy of Herman Chanowitz.

|

I remember

when Naples Capodichino airport looked like an airfield in documentaries

about WW2 —maybe even WW1: windsocks on the runway and strange

little people in goggles and flying scarves running around mowing the

airstrip and hand-cranking Fokker triplanes. Well, maybe not all that,

but there were no newfangled accordion tubes that snuggled up to the

side of the planes for easy on–and–offloading of contented

passengers. There were no contented passengers. There were no

busses, either; you walked out onto the tarmac to your plane. Sometimes

they got your bags out there before you left; sometimes they didn't.

Indeed, it was a throwback to those glorious early days of aviation.

They still spelled it "aeroplane," as I recall.

Since the

reinvention of mass tourism in the Bay of Naples, that has changed.

The sign now says "Naples International Airport" and the place deserves

the appellation. The passenger terminal was more than simply expanded;

it was rebuilt. It is new, spacious, and comfortable with all the bars,

shops and other creature comforts that one expects while one waits.

There is also ample parking, one of the few places in Naples to enjoy

that comfort so necessary to 21st–century creatures.

The

problem now is that no amount of expansion of the facilities (photo)

can handle the projected traffic. The paper this morning writes of the

grand plan to open up the military airport in nearby Grazzanise (about

35 miles from Naples near Capua) to passenger traffic. It was tried

once, out of necessity, some 15 years ago when the Capodichino airport

was partially closed for modifications. The plan, if it goes forward—and

that depends on complicated negotiations between the Italian air force

and various civilian agencies that have an interest in air traffic in

and out of Naples—is to route charter tourist traffic through

the new facility as early as this summer. Since much tourist traffic

is directed not to the city of Naples, itself, but to other areas of

the Bay such as Sorrento and the islands of Ischia and Capri, and since

the Grazzanise airport is near the A-1 autostada that runs into the

city, the plan might entail nothing more inconvenient than a slightly

longer bus ride for passengers, no matter what their destination. The

problem now is that no amount of expansion of the facilities (photo)

can handle the projected traffic. The paper this morning writes of the

grand plan to open up the military airport in nearby Grazzanise (about

35 miles from Naples near Capua) to passenger traffic. It was tried

once, out of necessity, some 15 years ago when the Capodichino airport

was partially closed for modifications. The plan, if it goes forward—and

that depends on complicated negotiations between the Italian air force

and various civilian agencies that have an interest in air traffic in

and out of Naples—is to route charter tourist traffic through

the new facility as early as this summer. Since much tourist traffic

is directed not to the city of Naples, itself, but to other areas of

the Bay such as Sorrento and the islands of Ischia and Capri, and since

the Grazzanise airport is near the A-1 autostada that runs into the

city, the plan might entail nothing more inconvenient than a slightly

longer bus ride for passengers, no matter what their destination.

Me, I have

a Fokker to crank.

Pizza

(1)

Sign

claims to mark the home of the first Margherita Pizza

I once

had a "Taco Pizza" in Honolulu. If pizza were human language, a discussion

would now follow on Grimm's Law, how pizza changes over time, creolization

of pizza, dialects of pizza, and very, very irregular verbs. Fortunately,

it's just pizza. The greatest recent innovation in pizza in Naples,

recently, is the cyber-pizza. Yes, you can actually walk into a pizzeria

down at Santa Lucia and have a pizza con funghi (mushrooms) while

you check your email and browse. I once

had a "Taco Pizza" in Honolulu. If pizza were human language, a discussion

would now follow on Grimm's Law, how pizza changes over time, creolization

of pizza, dialects of pizza, and very, very irregular verbs. Fortunately,

it's just pizza. The greatest recent innovation in pizza in Naples,

recently, is the cyber-pizza. Yes, you can actually walk into a pizzeria

down at Santa Lucia and have a pizza con funghi (mushrooms) while

you check your email and browse.

Speaking

of which, I did come across this:

| Lévi-Strauss

explores the semiotic properties of culinary practices as a model

for social ideology [to] express complex transformations of social

category systems. His remarks about attitudes to mushrooms suggest

the importance of historical experience for the retention of symbolic

associations between edible forms and cosmological concepts.

"Culinary

Semiotics" in Encyclopedic Dictionary of Semiotics. 1986.

|

I immediately

think when I read this that this Lévi-Strauss is one pretty "sharp

cookie" (I am, as you see, no slouch at food symbolism, myself). I mean,

besides inventing Blue Jeans and composing the Blue Danube Waltz, he

still has time to "get his licks in" (touché!) in the food column

of his local encyclopedia of semiotics. His insight about mushrooms,

alone, is worth its weight in—well, mushrooms.

Mushrooms.

Think. You are putting on your pizza something that is not animal, vegetable

or mineral. They are alive, yes, but so was the thing that burst out

of that guy's chest in Alien. Mushrooms are mycetes, fungi, and

"they are classified as something else!" (That's just they way my dictionary

puts it, too—italics, exclamation mark and all. It even has 'jitter'

lines around the phrase, like those old horror-movie posters, to make

you think that the words, themselves, are slowly moving towards you,

stalking you—but why talk about celery at a time like this? The

dictionary then adds: "Believe us, you don't want to know any more.")

Mushrooms

live in the dark, reproduce by spores and are spitting images (yuk!)

of those things that toads sit on, and if you, with a brain the size

of a bowling ball, can't tell the difference, what makes you think toads

can? Furthermore, some languages, such as Italian and German, use the

same word for "mushroom" as they do for whatever that gunk is that grows

between your toes in the condition known as "athlete's foot". Think

about that "symbolic association between edible forms and cosmological

concepts" the next time you order pizza con funghi. Or, as we

food–semiotics say: "How do you like them apples?!"

I know

a Neapolitan woman who, for ideological reasons, refuses to eat any

other pizza but the "Margherita". It seems that that pizza was named

in the last century in Naples for the first queen of united Italy, Margherita

of Savoy (1851-1926), wife of Umberto I. When the royal family was in

Naples, they stayed, of course, at the ex-Bourbon Royal Palace. (Why

waste a good palace just because it belonged to a previous dynasty?)

A few blocks away from the palace, just off of Via Toledo (also known

as via Roma) is a ristorante cum pizzeria named Brandi

(photo above), one of the most historical of such establishments in

Naples. Among the many items of interest on the walls, next to all the

pictures of the rich, fat and famous who have eaten there, is the story

of how their chef concocted the first pizza Margherita for Her Royal

Highness and took it over to the palace, himself. (What was he going

to say—"We don't deliver." ?) The colors of the makings—green

(basil), white (mozzarella) and red (tomato)—stood for the national

colors of the new nation. (Right, whenever the flag was paraded by,

every pizza in Naples rose. It was the yeast they could do.) The socio-political

ramifications are, indeed, getting deeper and deeper here. Why, for

example, does one even put "Basil" on a pizza? After all, he was a Greek

prelate who lived from 330 to 379 a.d. and who was the Bishop of Caesarea.

Or mozzarella?

Something which comes from the udder of a buffalo?! Now, except for

that admittedly touching film about buffaloes that dance with wolves,

or whatever, what are the other associations you have for "buffalo"?

See what I mean?—"Buffalo Gals," "buffalo breath" and "buffalo

chips". I am too young to remember exactly–or even approximately–what

"Buffalo Gals" were (except that they apparently liked to "dance by

the light of the moon") but I do have, modestly, a passing familiarity

with the breath and the chips, and I say, "No, thank you."

And tomato?

Now that you have worked yourselves into a semiotic feeding frenzy,

you are no doubt asking yourselves why the archaic slang of detective

fiction refers to a beautiful woman as a "swell tomato", as in "Geez,

boss, dat sure wuz some swell tomato you wuz wit'," when it should be

clear even to those with marginal IQ's that the adjectival participle

of "swell" is "swollen". Ergo: "Geez, boss, dat sure wuz some swollen

tomato you wuz wit'." I did, however, see a "tomato" once with a "pair

of gazoombas that would stop your heart". The only reference I have

been able to find to "gazoomba" is in my English-Quechua dictionary.

It is an ancient Incan word for "mushroom".

Coppola,

Villaggio

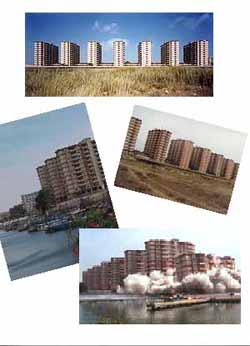

And

then there were five. I am talking about the infamous "Towers" along

the Flegrean coast, a long stretch of potentially beautiful beach at

Castel Volturno, just up the coast from Naples. Officially, the towers

were known as the Villaggio Coppola, built by the Fontana Blu Corporation,

owned by the Coppola bothers. And

then there were five. I am talking about the infamous "Towers" along

the Flegrean coast, a long stretch of potentially beautiful beach at

Castel Volturno, just up the coast from Naples. Officially, the towers

were known as the Villaggio Coppola, built by the Fontana Blu Corporation,

owned by the Coppola bothers.

The entire

complex included eight 15-story apartment houses (the "Towers"), adjacent

hotels, restaurants, a small boat harbor—an entire small city

and, collectively, one of the ugliest examples of illegal, "wildcat"

construction in Italy. Having said that, it is worth noting that they

were built largely to house members of the US military. That particular

need is no longer served since the US Navy now has its own satellite

city in nearby Gricignano—built on property owned by the Coppolas.

(Perhaps there is a book waiting to be written about the relationship

of the US government to the Brothers Coppola.) The towers, they say,

were an example of what you could get away with a few decades ago with

large envelopes of cash. ("Oh, what's that over there?" you would say,

pointing into the distance. Then, while the building commissioner was

distracted and staring off into space for two or three years, you—with

no building permit—put up your "ecomonsters," as the press calls

them.)

Over the

years, I have driven up past that stretch of coastline and have grown

accustomed to glancing over and seeing that row of ugly monolithic dominoes

on the beach—"Pukehenge," we used to call it. The were horribly

visible from a distance and perhaps even from low orbit. Yesterday,

I looked over and did a happy double-take. There was one missing. They

had blown it to smithereens while I wasn't looking. Today the newspaper

reports that at 3 pm another explosion will devour two more of them.

That will leave five, and they are scheduled for demolition in April.

It's almost worth the drive to watch.

|