©

2004 Jeff Matthews & napoli.com

Language/s

(3)

Here’s

another bit of off–the–cuff anthropology. It is related

to the entry here and my perception that there is less of

a difference between “insider” and “outsider”

in Naples than in many other places. Perhaps it relates also to the

local ability—or lack thereof—to learn foreign languages. Here’s

another bit of off–the–cuff anthropology. It is related

to the entry here and my perception that there is less of

a difference between “insider” and “outsider”

in Naples than in many other places. Perhaps it relates also to the

local ability—or lack thereof—to learn foreign languages.

Anyone

who teaches English as a foreign language abroad (as I do) comes away

with the feeling that some cultures are better at it than others. A

cursory stroll down almost any street or into any store in northern

Europe will leave you with the impression that everyone—say, in

the Netherlands—speaks English. Movies and TV are routinely in

the original language and subtitled in Dutch, and local children will

no doubt hear thousands of hours of English before they get a chance

to study it formally in school. They are primed for French and German

in much the same way. It is a polyglot culture.

In Naples—and

in Italy, in general—everything is dubbed into Italian. Young

people seem to approach the study of another language the way they do

Latin in school—as a dead language, totally unconnected to their

daily lives. They almost never experience English directly. Admittedly,

the onslaught of American popular music has modified that somewhat,

so that a sentence such as “How ya gonna do it if ya really

don’t wanna dance?” is part of the same local perception

of the English language mosaic as, “Little we see in Nature

that is ours;/We have given our hearts away, a sordid boon!” It’s

all English. It’s in the same ballpark. (That can cause a few

problems at exam time. EBL—English as a Ballpark Language? Maybe.)

So, my

sharp and highly intelligent students in Naples don’t really care

that indirect questions follow normal subject-object word order and

not that of direct WH-questions. They say, “Do you know where

is the station?” and are quite amused at my insistence on “Do

you know where the station is?” And I can see “What difference

does it make? You understand me, right?” running through their

minds. Maybe that is related to the fact that Naples is a "survivor

culture". They are a flexible, hospitable and outgoing people—and

totally undemanding of you when it comes to your own ability

to speak their language. They will gratefully accept any kind of Italian

from you and thank you for it and sincerely compliment you on it. You

become an “insider” almost by declaration. You say in your

worst Italian, “Hey, I want to belong” and their answer

is “Fine. No problem.”

You communicate

anyway, even without proper verb conjugations, and those little niceties

of language fall by the wayside as the difference between insider and

outsider gets more and more muddled. You communicate, and it is almost

like being present at one of those mighty births of creole language

that linguists tell us occur when cultures and languages blend. Thus—here’s

the point (you knew there had to be one in here, somewhere!)—Neapolitans

are as willing to accept their own mistakes in other languages as they

are to accept your mistakes in theirs.

Yes, there

are cultures in the world that are so xenophobic that they reject any

attempt on your part to speak their language, much less take out membership

in that culture. If that is one end of the spectrum, there certainly

must exist cultures at the other end—the place where all the “flexible,

hospitable, outgoing and undemanding” xenophiles gather and get

along.

Anacapri

Looking

from the town of Capri towards Montesolaro and Anacapri. Looking

from the town of Capri towards Montesolaro and Anacapri.

My friend,

Bill, keeps encouraging me to read Graham Greene because that author

is so depressing, cynical, and writes so well. Thus, almost at random,

I found this from Greene's This Gun for Hire.

| He

had been made by hatred; it had constructed him into this thin

smoky murderous figure in the rain, haunted and ugly. His mother

had borne him when his father was in gaol, and six years later

when his father was hanged for another crime, she had cut her

own throat with a kitchen knife; afterwards there had been the

home. He had never felt the least tenderness for anyone; he had

been made in this image and he had his own odd pride in the result;

he didn't want to be unmade. |

Is there

a special reason why the person who wrote that passage—almost

a caricature of Evil—chose to live in Anacapri, or why he called

attention to the fact that he regarded the town not only as a place

to have a house, but a home, or why he was especially proud of the honorary

citizenship bestowed upon him by that community?

The passage

cited has at least a little to do with Greene's perception of the presence

of evil in the world. It's everywhere. The world, after all, is a seedy

and decaying pit with absolutely no guarantee that good will win out,

for there is no assurance that good persons in the world can be counted

on to do good. It may go even further than that: there may be no good

persons to speak of! Or, at least, if there are, they are helpless in

the face of the irresistible nature of evil. It is stronger than we

are. What, however, does that have to do with Capri, and, specifically,

Anacapri?

Perhaps

it is best to think of the Isle of Capri precisely the way it looks

as you approach it from the sea—as two different places. And for

those of you who don't know, those of you who have blindly accepted

the arrogant cartographic hoodwink that 'Capri' is Capri, well, that's

not so. The island is, in fact, two different places: one low and one

high—Capri and Anacapri. According to a good source of mine, a

young woman from Anacapri, this physical configuration of the island

corresponds perfectly to the differences between the residents of the

two towns, Capri and Anacapri, in that the Anacapresi are morally and

spiritually superior to the inhabitants of the town of Capri. After

all, she claims, monks don't go down into mineshafts to meditate, they

go to the tops of mountains. And since she is morally superior, she

wouldn't lie about that, either.

Look at

the infamous piazzetta, the town square of Capri. Here you find prodigal

ne'er–do–wells wallowing in cafes and bars, smoking and

lounging on the steps of a church (!), aimlessly wandering around, drinking

too much and buzzing too much in that nervous stirred-up fashion of

swarming insects trying desperately not to notice that the façade

they are clinging to is cracking. These are, you must admit, at least

potentially "smoky murderous figures" (see above). (For you democrats

out there, we are not presuming guilt, here, merely presuming evil—an

entirely different matter.) These are your jet-setters, the 'lovely

people', people out for a 'good time' ('good', of course, not in the

proper theological sense of 'morally correct' but in the perverted modern

sense of 'that which produces ephemeral physical pleasure and a nice

suntan'). Here is where you can well imagine a character in one of Graham

Greene's novels sitting and brooding about having been 'made by hatred'

or being 'haunted and ugly' and not 'feeling the least tenderness for

anyone'.

On the

other hand, high up the hill, past the protective bulwark of the hermitage

of S. Maria Cetrella perched on the cliff, and, thus, well above Man's

Fallen State, iniquity gasps like a carp out of water. There lies Anacapri,

where there is only one real square, to speak of, and that is in front

of the Church of Santa Sofia. There is no brooding or sulking here,

either. (It is illegal ever since the town fathers erected that 'No

Brooding or Sulking' sign that dominates the square). It is here that

we truly realize for the first time why 'Anacapri' and 'good' rhyme

(at least they do in Lepcha, a minor dialect of the Sino-Tibetan family

of languages, but perhaps I digress).

Not only

that, but the square of Santa Sofia is only a few minutes from the chair–lift

to the top of Monte Solaro. If and when the Evil–alarm went

off, Graham Greene was just a moment away from salvation, from transcending,

moving ever upward like Dante after Beatrice, or Goethe after the royalties

on Faust, for Evil, especially southern Mediterranean Evil, has been

shown not to be particularly viable above 250 metres, unless there is

a lot more annual rainfall than one normally finds on the slopes above

Anacapri (see "smoky murderous figure in the rain", above). All in all,

then, perhaps it is only in Anacapri that Graham Greene may have been

somewhat less convinced of the all–pervasiveness of Evil. And

that's not so bad, is it?

Cimarosa,

Domenico (1749-1801)

Cimarosa was the most highly regarded

Italian composer of his day (this, just in case you have been tricked

by the film Amadeus into thinking that this honor belongs to

a Viennese court composer by the name of Salieri). Cimarosa was the most highly regarded

Italian composer of his day (this, just in case you have been tricked

by the film Amadeus into thinking that this honor belongs to

a Viennese court composer by the name of Salieri).

Cimarosa

was born in Aversa near Naples and was admitted to the Conservatorio

di S. Maria di Loreto in 1761 where he made rapid progress

as a violinist, keyboard player, singer and, above all, a composer.

He left the conservatory in 1771. He first gained a broader reputation

by his contributions to the opera buffa, the unique Neapolitan

music form that had become the rage of Europe ever since Pergolesi's

La Serva Padrona decades earlier. Cimarosa's early works such

as Le stravaganze del conte, Le magie di Merlina e Zoroastro,

Il ritorno di Don Calandrino, Le donne rivali, and Il

pittore parigino belong to the rather large body of light-hearted

and neglected music from the 18th century, much of which has simply

been historically overrun by works in the same vein by Mozart

and Rossini, as well as by the changing tastes in music

when all of art was swept into the great age of Romanticism.

In

1785 Cimarosa was appointed second organist of the Neapolitan

royal chapel and also held an appointment at the Ospedaletto conservatory

in Venice. In 1787 Cimarosa accepted the position of maestro di

cappella at the St. Petersburg court of Catherine II. On

the way to Russia, Cimarosa made the acquaintance of the Grand

Duke Leopold of Tuscany, who later, as emperor (1790-92) would be

helpful to him during his stay in Vienna. He also met Caroline, the

Vienna-born wife of King Ferdinand of Naples—a woman who would

loom large in his own future in another few years.

Cimarosa

stayed in St. Petersburg until 1791. He was one of a long line of Italian

composers employed by the Czarina. He returned to Vienna where he was

appointed Kapellmeister by Leopold II. He wrote a number of comic operas

there, most notable of which was Il matrimonio segreto, based

on The Clandestine Marriage, a farce by Colman and Garrick from

1766. It was enormously successful and is, today, still one of the very

few Neapolitan comic operas in the standard repertoire of opera companies

in the world. It usually runs in Naples every two or three years.

He returned

to Naples in 1796 and became the first organist of the royal chapel.

He immediately became embroiled in the politics of the day, that is,

the republican fervor sweeping Europe in the wake of the French Revolution

of 1789. When the Neapolitan Republic was declared in 1799 and the royal

family fled from Naples to Sicily, Cimarosa lent his skills to

the cause of the new Republic and composed a patriotic hymn that became

the "national anthem" of the Republic.

When the

Republic fell and the Bourbons returned to power in Naples, Cimarosa

tried to make things right by composing some music for his old acquaintance,

Queen Caroline, and her husband, King Ferdinand. Both king and queen,

however, were hell-bent on revenge, and Cimarosa was one of the one-thousand

"Republicans" put on trail for treason. He spent four months in prison

and was spared execution probably by the intervention of his friends,

Cardinal Ruffo and Lady Hamilton, and

by his own plea at his trial that we was merely a composer. Yes, he

had composed that Republican hymn, but he had also written music in

honor of the royal family. That's what composers do: you pay them, they

compose music. Whatever the reason, the "hanging judges" of the Bourbon

tribunal let him go with exile. Cimarosa moved to Venice where he died

in 1801. Despite rumors that Queen Caroline of Naples had him poisoned,

he most likely died of natural causes.

[Other

items related to the Neapolitan Republic are:

The Bourbons in Naples (1)

Eleonora Fonseca Pimentel ]

Though

now overshadowed, Cimarosa enjoyed vast renown during his lifetime.

His 60 stage works were performed in all the major European capitals.

He was praised by the likes of Goethe and Stendahl. His music was vigorous,

yet elegant and delicate—of the kind that is today termed "Mozartean"—particularly

the orchestral passages in, say, Il matrimonio segreto. Ironically,

that work was premiered in Vienna in 1792, the same year that Mozart

died there. It is, perhaps, an understandable quirk of history that

relegates fine artists such as Cimarosa to obscurity in comparison to

their larger-than-life contemporaries; in this case, that would be Haydn,

Mozart and Beethoven. Tough competition, indeed.

[See,

also: The Naples Conservatory and Mozart

and The Neapolitan Comic Opera.]

Albergo

dei Poveri (Royal Poorhouse)

When Naples is viewed from a certain height, one of

the most visible structures in the city is the gigantic Hospice for

the Poor on via Forio. As they say, you can’t miss it. It is 300

yards long and five stories high (17th-century stories, meaning about

as high as 7 or 8 modern ones). Decayed façade, windows gone,

upper floors and much of the roof fallen in, it’s a shell—a

dead mastodon that has simply not yet fallen over. I have passed it

a thousand times and thought, “Either do something with it or

knock it down”. When Naples is viewed from a certain height, one of

the most visible structures in the city is the gigantic Hospice for

the Poor on via Forio. As they say, you can’t miss it. It is 300

yards long and five stories high (17th-century stories, meaning about

as high as 7 or 8 modern ones). Decayed façade, windows gone,

upper floors and much of the roof fallen in, it’s a shell—a

dead mastodon that has simply not yet fallen over. I have passed it

a thousand times and thought, “Either do something with it or

knock it down”.

About six

months ago, they restored the façade around the main entrance

to the building, so it seems they have taken the first option. I finally

got into the building yesterday on a guided tour and, indeed, there

is considerable clean-up going on of rubble and the accumulated junk

of decades of neglect, a job that has to be done before real restoration

of the building can take place.

The Hospice

for the Poor was ordered built in 1751 by Charles III, the first Bourbon

King of the Kingdom of Naples. It was designed and started by Ferdinando

Fuga and then continued by Luigi Vanvitelli, the great architect of

the Bourbon Royal Palace in Caserta (the so-called “Versailles

of Italy”). The idea, in those days, of constructing a mammoth

poor house along via Foria, one of the principle entrances to the city

of the eighteenth century, was in keeping with promoting the image of

Charles III as an enlightened monarch and the image of his kingdom as

one of compassion. It was also in keeping with a wave of such “social

construction” throughout Italy in that century in the form of

poor houses, hospitals and communal granaries. (Indeed, in Naples, there

was even a grotesquely efficient paupers’ graveyard with a numbered

communal plot for each day of the year.)

The original

plan for the Hospice was to have one long façade fronting five

internal courtyards, the central one of which would house a high-domed

gigantic church that was to be the inner hub of the entire building;

from that hub, passage ways were to radiate out to dormitories, dining

halls, workshops, and gardens. It was actually envisioned as a sort

of self-sufficient small village. The intentions of Charles III were

never fulfilled. The anti-clericalism of French rule between 1806 and

1814 in Naples put an end to the central church, and two of the five

courtyards were eliminated, thus giving the present configuration of

one central courtyard and one on each side. Thus, by 1820 the plan to

build a poor house bigger than most royal palaces had become much less

ambitious.

That part

of the building that had been finished, however—and it was impressive—

remained in use through WW2, and in its long history the Hospice has

housed everything from trade schools to hospitals to the back-up archives

for the city of Naples. After WW2 they even put in a football field

in a courtyard to keep the local kids out of trouble. Also, there are

currently some 85 families living in the building, housed in flats around

the courtyard behind the east third of the façade. They are,

by now, the grandchildren of the needy families that were situated there

after WW2. Thus, even in its unfinished state, it has served the city.

Real neglect

began after WW2, and the last 50 years have been a disaster. Also, the

building suffered considerable damage in the earthquake of 1980; yet,

the consensus is that it is still structurally sound. In 2002 the main

entrance and adjacent rooms were restored as part of a "teaching project"

to help build a cadre of masons, builders and artisans trained in historical

restoration. The restored section is open and houses exhibitions of

one sort or another. In February 2003 plans will be approved to restore

the entire building by 2006. They call for a restoration to the "unfinished"

state of the early 1800s. That is, no attempt, for example, will be

made to build the mammoth church that was originally planned for the

main courtyard of the building. The various rooms will then be available

for various functions and possibly even private enterprises that do

not "offend" the history of the building. No MacDonald’s on the

premises, one may assume.

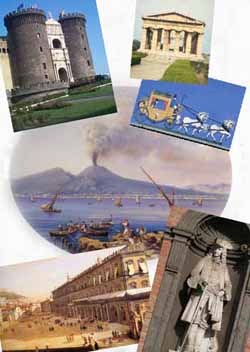

Grand

Tour

I

was chugging down Via Caracciolo the other day on my four 14-year-old

cylinders. The 18th-century Royal Gardens—now a public park—were

on my left, and coming up on the right was the Castel dell'Ovo,

built on the site of the original Greek settlement of Naples, later

also the site of the last prison of the last emperor of Rome. I was

sort of enjoying the 'history' of it all, when I noticed a gigantic

tour bus in the rear-view mirror, about ready to blast by me. They were

in a hurry—definitely not on a Grand Tour. I

was chugging down Via Caracciolo the other day on my four 14-year-old

cylinders. The 18th-century Royal Gardens—now a public park—were

on my left, and coming up on the right was the Castel dell'Ovo,

built on the site of the original Greek settlement of Naples, later

also the site of the last prison of the last emperor of Rome. I was

sort of enjoying the 'history' of it all, when I noticed a gigantic

tour bus in the rear-view mirror, about ready to blast by me. They were

in a hurry—definitely not on a Grand Tour.

If you

define 'grand' as 'extravagant' or 'leisurely' or 'relaxing', then whatever

else traveling is these days —fast, convenient, cheap— one

thing it is not is 'grand'. I say this in spite of being totally

seduced by the idea of sub-orbiting from Europe to Japan in two-and-a-half

hours aboard a hypersonic ram-jet spaceplane. But it will still take

me forever to fight my way through traffic from my house to the hypersonic

ram-jet airport, and once aboard, I will be force-fed hypersonic ram-jet

spaceplane food, and at my destination be corralled into a holding pen

waiting for one surly bureaucrat to rummage through my underwear while

another compares my passport photo to Interpol mugshots. Good, you get

there, but 'grand' it ain't.

'Grand',

as in The Grand Tour, means going back to the eighteenth and early nineteenth

century and taking a few months off to travel around Europe and complete

your education on lots of daddy's money. You traveled by ship, train

(from the early 1800's onward) and horse-drawn barouche or dormeuse.

You didn't wear bowling-shirt and tennis shoes, either. You packed burnouses,

cloaks, frocks, spencers, waistcoats and a nice selection of cravats

and collars —after all, you would be dressing for dinner, a leisurely

affair with educated conversation before, during and after, enlivened,

of course, by your own sparkling wit.

The Grand

Tour was the last act in the eighteenth-century English and northern

European gentleman's coming of age. You had just spent your entire formative

years studying things like alea iacta est ("The die is cast").

You had totally ignored, of course, the glorious daredevilry of Caesar's

words as he crossed the Rubicon, and had concentrated, instead, on what

the correct Latin would have been had Julius wanted to say something

like, 'The die would have been cast,' or, maybe, 'Might have been cast,'

or, even 'Hey, what happened to the other die?'

Now you

were off to do some cultural empire building of your own: around the

Continent —Paris, Vienna and then the grand finale of the Grand

Tour, south to Italy—across the Alps and down into sun, music,

art, romance, hurtling back to the dark intrigues of Renaissance Italy,

then back further to the glories of Imperial Rome, to the beginnings

of Christianity and then the ancient Greek outposts of the southern

peninsula. For well over a century, young northern gentlemen swarmed

through Italy so they could get what a thousand books could not give

them, so they could personally explore millennia of history upon which

their civilization was built, so they could tread where Michelangelo,

Dante, Augustus, Virgil, Peter, and even Ulysses had trod.

Byron,

Shelly, Goethe, Mozart, Stendahl… and on and on—they all

came to Italy, and most of them came to Naples, the southernmost point

on the standard Grand Tour. In the 18th century, visitors to Naples

found a city rebuilt by Charles III of Bourbon: royal palaces, broad

streets, the finest opera house in the world —a city entirely

to suit the opulent tastes of the monarch and then of his Habsburg daughter-in-law

who would run the kingdom (while her milksop husband 'ruled') until

well into the19th century.

Visitors

thus enjoyed the splendor of the modern absolute monarchy. It was here

that Stendahl, at the reopening of the San Carlo Theater said that he

felt as if he had been "…transported to the palace of some oriental

emperor…my eyes were dazzled, my soul enraptured. There is nothing

in the whole of Europe to compare with it." It was here, too, that even

the sombre Goethe—who complained that his "German temperament

and determination to study" kept him from amusing himself—relaxed

enough to write:

| I

can't begin to tell you of the glory of a night by full moon when

we strolled through the streets and squares to the endless promenade

of the Chiaia, and then walked up and down the seashore. I was

quite overwhelmed by a feeling of infinite space. To be able to

dream like this is certainly worth the trouble it took to get

here. |

Perhaps

he begrudged the natives their easygoing approach to life more than

a little when he observed that in Naples "…as long as the queen

is pregnant and the king is off hunting, all is right with the world."

But, primarily,

they got the past they had come for. Naples is where classical Greece

first came ashore beyond the Aegean; even the mysterious Etruscans and

Samnites had been in Naples; Hannibal had laid siege to it, and Spartacus

had led his revolt on the nearby slopes; here Brutus plotted the assassination

of Julius Caeser; here the last emperor of the Western Empire was exiled;

nearby was the mythological descent into the Underworld, and Virgil

wrote the Aeneid here—indeed, the poet is buried in Naples, and

his tomb is a shrine now as it was during the age of the Grand Tour.

Visitors were fortunate enough, too, to get in on the first massive

modern excavations of Pompeii and Herculaneum. They could climb famed

Vesuvius, the eruption of which had killed Pliny the Elder and destroyed

Pompei, an event which moved Grand Tourist Shelly, 1,800 years later,

to pen in his Ode to Naples:

I

stood within the city disinterred;

And heard the autumn leaves like light footfalls

Of spirits passing through the streets;

and heard The mountain's slumberous voice at intervals

Thrill through those roofless halls.

The oracular thunder penetrating shook

The listening soul in my suspended blood.

I felt that Earth out of her deep heart spoke… |

So, as

the bus went by me I frantically signaled to the tourists trapped within.

I made what I was sure were universal gestures for "18th century royal

gardens" and "…the last prison of the last emperor of Rome". Stop,

I said, beckoning them to tarry a while and partake of genteel discourse—in

short, to 'get grand'. It was too late. They were gone, on their way

back to the airport.

Immigration

(2), Neapolitan culture (4),

extracomunitari, urbanology (3)

In Italian,

the term extracomunitari refers to those persons from outside

the European community. Technically, that includes Canadians, citizens

of the USA, Australians, and Martians—and it is true that citizens

of those countries and planets stand in the extracomunitari queue

in airports. Yet, in general terms, everyone in Naples knows what extracomunitari

really means. It refers to Asians, Africans and people from the Balkans

who wash up on southern Italian shores in search of a new life. Very

often, they really do wash up on the shores, having been abandoned by

heartless refugee smugglers who think nothing of dropping a pregnant

woman into the sea, 100 yards from shore, and speeding off to pick up

another boatload of people who will do anything to get into Europe.

These people

who have deserted their homes, families, friends, and native language

in Albania or Morocco, or wherever, generally find Naples to be a city

with a good heart. (I have never (!) heard a racial slur against

these people. You know—“Hey, why don’t all these black

people go back where they came from.” I have heard: “Are

you nuts? We haven’t got any jobs for ourselves! But if you want

to slog it out on the streets, more power to you.”)

Many of

the immigrants wind up in the grey world of peddling wares of one sort

or the other on the streets, either on Via Toledo or Corso

Umberto, two of the main drags in town. They lug their goods to

and fro in those huge zippered duffel bags of the kind that scuba divers

use. They generally set up right on the sidewalk: first a tarp—or

maybe just large piece of cardboard—on the ground, and then they

unload the leather handbags and belts, assorted trinkets, even small

African musical instruments and carved animals. Some of those may even

have been carved in Africa, though maybe they were done at “home”

in Torre del Greco, a town near Naples right on the slopes of Vesuvius.

Many of the African extracomunitari live there, sharing flats—nothing

unusual in what is, anyway, the most densely populated area in Europe.

Usually,

they are left alone, even by the police. Yet, there is such a thing

as “vendor overload” on any given street, I suppose, and

if they are set up right in front of your store on the sidewalk and

selling tax-free contraband handbags and draining customers away from

your shop that sells the real taxed deal—well, then, you are going

to call the cops and let the chips fall where they may.

That’s

what happened yesterday on via Roma. The police move in on street

vendors with all due lack of deliberate speed. The point is not to arrest

25 poor bastards and confiscate their stuff; the point is to roust them,

send them packing and give the merchants of the area a breather. The

extracomunitari peddlers have a nose for trouble and the minute

the roust starts up at the end of via Roma, the grapevine is

electrically fast; within seconds they are gone—right down to

the end of the street they have packed up and left in no time flat.

Yesterday,

a young Senegalese by the name of Djouf was a bit slow in gathering

up his stuff. He got the word —“Cops!”— but

he stuck around a second or two longer than the others, just to make

sure that he hadn’t left any of his wares behind on the sidewalk.

That’s when the police moved in on him, as the law provides, to

“check his papers”. And that’s when the street people

moved in on the cops. A crowd of residents of the popular Spanish Quarter

quickly surrounded the “Forces of Order” (as the Italian

euphemism has it) and demanded Djouf’s release. Push came to shove,

but the long and short of it is that the police backed down. Djouf not

only got released but was carried away on the shoulders of the crowd,

like in Hollywood where Robin Hood gets sprung from the clutches of

the king’s men by the villagers. It is certainly not that simple.

The police chief’s view in the papers today was, “Fine.

You tell us what you want us to do. You called us, remember?”

Taxis,

petty theft (2)

I

have a normal and healthy paranoia when it comes to taxis. I know that

the driver is going in circles and even weirder geometries just to run

up the fare on me. He recognizes me as a stranger in a strange land

and is taking me to the cleaners even though that establishment is nowhere

near my house. So, in an unwonted eruption of fairness, I inform you

that the other day a Naples cab driver got his picture in the papers.

He found a bag with twelve-thousand euros (a tad more than $12,000)

in the back of his cab, did a bit of sleuthing in his passenger-log

for the day and figured out who it might have been. He was right. One

phone call and the lucky passenger got his money back. The consensus

of opinion at the local coffee bar is that if the sum had been ten times

that amount, then it could only have belonged to a plutocrat swine who

would have deserved to lose the money. This is solid trickle-down economics

that we tamper with only at great peril. On the other hand, twelve grand

is a lot of money, but it’s not a fortune. I offered the view

that “maybe it was a guy just like you or me”. The bar-owner

smiled and said, “Do you walk around with that kind of money in

your pocket? If so, step into the back room. I have a black-jack I would

like you to meet.” The jury hung and we declared a mistrial. I

have a normal and healthy paranoia when it comes to taxis. I know that

the driver is going in circles and even weirder geometries just to run

up the fare on me. He recognizes me as a stranger in a strange land

and is taking me to the cleaners even though that establishment is nowhere

near my house. So, in an unwonted eruption of fairness, I inform you

that the other day a Naples cab driver got his picture in the papers.

He found a bag with twelve-thousand euros (a tad more than $12,000)

in the back of his cab, did a bit of sleuthing in his passenger-log

for the day and figured out who it might have been. He was right. One

phone call and the lucky passenger got his money back. The consensus

of opinion at the local coffee bar is that if the sum had been ten times

that amount, then it could only have belonged to a plutocrat swine who

would have deserved to lose the money. This is solid trickle-down economics

that we tamper with only at great peril. On the other hand, twelve grand

is a lot of money, but it’s not a fortune. I offered the view

that “maybe it was a guy just like you or me”. The bar-owner

smiled and said, “Do you walk around with that kind of money in

your pocket? If so, step into the back room. I have a black-jack I would

like you to meet.” The jury hung and we declared a mistrial.

The seamier

side of human nature—and this one restores my faith—has

to do with the small local Church of San Giuseppe a Chiaia (photo) just

across from the Villa Comunale, the large public gardens that

extend along the seaside from Mergellina to Piazza Vittoria.

One of the priests noticed that the same gentleman came in early every

morning to pray. He always sat in the same pew near a small collection

box, a simple affair secured with a locked, hinged top with a slot in

the top where you can drop in a few coins if the spirit so moves you.

The priest also noticed that the collection box—far from being

coinful unto overflowing from the generosity of the previous day’s

faithful—was empty most of the time. Sleuthing, again, came into

play, the inductive chain proceeding thusly: (1) box full of coins;

(2) man comes in; (3) man goes out; (4) box empty. Eleemosynary, Watson!

An undercover cop—posing as I’m not sure what…a confessional?—caught

the scoundrel extracting coins back out of the box through the slot

using a wooden stick with a piece of chewing gum on the end of it. “But

I was just ‘doing alms’—as our Lord and Saviour bade

us,” he said. This radical approach to New Testament hermeneutics

did not wash with the judge. The blackguard got 3 months. He has promised

to reform—or at least change churches. Maybe he will apply for

a job as a cabbie.

Streets

(1)

Lovely

Rita, a dear friend who used to live in Naples, has just written. She

says:

| Last

weekend we were in San Francisco and we drove the kids down Lombard

Street which claims it is the crookedest street in the world.

I remember a street in Naples that was kind of hidden that was

at least equally as crooked. I believe it ended up at Mergellina…what

can you tell me about this very old street? |

I'm

not sure. She has described a number of streets in that area. She might

be talking about Rampe S. Antonio (photo), a road that makes

seven 180–degrees turns to navigate down the hillside from above

the Church of Piedigrotta and comes out a couple of blocks

from the small Mergellina harbor. It's not a major thoroughfare,

so maybe that doesn't count in the "world's crookedest street" contest.

Off hand, however, I can think of a few busy roads in the city that

make two or three "180s" with a few right–angle turns thrown in

over the length of half a mile or so. I'm

not sure. She has described a number of streets in that area. She might

be talking about Rampe S. Antonio (photo), a road that makes

seven 180–degrees turns to navigate down the hillside from above

the Church of Piedigrotta and comes out a couple of blocks

from the small Mergellina harbor. It's not a major thoroughfare,

so maybe that doesn't count in the "world's crookedest street" contest.

Off hand, however, I can think of a few busy roads in the city that

make two or three "180s" with a few right–angle turns thrown in

over the length of half a mile or so.

That is

what happens when a city is spread from sea level to about 600 feet,

as is Naples; roads have to be either very crooked or very steep and

maybe even both. For pedestrians there are also four heavily–used

cable–cars in Naples. (They are also termed “funicular railways,”

as in "Funiculì–Funiculà,”

though that song was written about the long–gone cable–car

on Vesuvius). And only brave sherpa Tenzing Norkay would feel much like

singing on the way up the many stairways that web the hillside.

The original

Greek (and then Roman) city was laid out on a neat grid of symmetrical

blocks. (Pythagoras, himself, would whack a stone surveyor’s tripod

across your brow if you tried to sneak in even one little dogleg.) There

were no crooked roads. After centuries of wandering around in

the Dark Ages, however, people had simply reinvented crookedness on

their own. Then, in the sixteenth century, the Spanish straightened

a lot of that out. Ironically, the Baroque—known for complexity

and ornateness—oversaw the construction of broad, straight roads

in Naples for the first time in 1500 years. The famous Spanish Quarter

in Naples was built during that period. (I include a quote from the

entry for July 5 about the Spanish Quarter)—

| Here,

one does well to recall Lewis Mumford’s remark that

the clearing away of the small winding medieval streets of Paris

by Napoleon III in the mid-nineteenth century did away with the

last physical barrier which protected the common citizen from

the power of the absolute state. Such was the case in Naples —

a long rebellious nest of medieval clutter into which the King’s

soldiers ventured at considerable risk was made more manageable

by the introduction of broad straight roads that were easy to

patrol. |

If my friend is looking for steep streets, I think via Kagoshima takes the

prize in Naples, though others come close. That's the name, tooóKagoshima.

That Japanese city and Naples have paired off in one of these "sister

city" affairs. Presumably, in Kagoshima there is a street named after

Naples. I took a carpenter's level over to via Kagoshima the other day

just to check my little car's complaint that the street has a 45Ėdegree

grade, at least in part. The tiny air bubble went way over to one side. I

don't think I got an exact readout of 45 degrees, but I remember thinking

that if I used that carpenter's level to make tables like that, I could

sell them to people who just wanted to sit at one end and have all their

food roll down to them.

We don't

worry too much about crooked and steep; it's "holeyness" we are concerned

with. We had a sink-hole a few years ago up on the Vomero hill, above

the main part of Naples, that opened and swallowed a filling section.

Folklore already insists that the filling station has never been found.

It has become a Texaco Flying Dutchman, doomed to sail the netherworld

of Naples forever.

Circus—

There

is cause for rejoicing under the big–top today. At the same Moira

Orfei circus, a Siberian camel named “Tibet” gave birth

the day before yesterday to a bouncing baby girl, named “Magic”

(after the “Magic World” amusement park where the circus

is running). The calf is healthy and as snow white as her mother. Mother

picked a good day for the event; the circus was taking its one day in

the week off; this gave jugglers, clowns, and acrobats a chance to pace

worriedly and pretend they know something about dromedary obstetrics.

By the way, There

is cause for rejoicing under the big–top today. At the same Moira

Orfei circus, a Siberian camel named “Tibet” gave birth

the day before yesterday to a bouncing baby girl, named “Magic”

(after the “Magic World” amusement park where the circus

is running). The calf is healthy and as snow white as her mother. Mother

picked a good day for the event; the circus was taking its one day in

the week off; this gave jugglers, clowns, and acrobats a chance to pace

worriedly and pretend they know something about dromedary obstetrics.

By the way,

| Middle

English dromedarie <Old French dromedaire <Latin

dromas < Greek dromas, a runner <dramein,

to run < Indo.European base *drem–, *dreb–,

to run, whence Sanskrit drámati [he] runs, TRAMP.) |

[Don’t

you get the feeling that etymologists are just having a good time with

you sometimes?]

Anyway,

the father, Pippo, is also doing well and is strutting his hump around

the tent.

Like many,

I have mixed feelings about animals in zoos and circuses. I went to

the Naples zoo once many years ago and vowed never to go back. They

had a beautiful Siberian tiger in a very confined space, and the animal

had obviously gone “stir crazy”. I wanted somehow to release

it and let it run out and go down fighting—after it polished off

a band of obnoxious teenaged moron who were taunting their chimpanzee

first-cousins in a nearby cage by throwing debris through the bars.

Emigration,

immigration (3)

Emigration

occupies a good deal of space in the collective psyche of southern Italy.

Everyone seems to have a brother, cousin or uncle who has gone away

to find work and never come back. Indeed, even though the great waves

of emigration from southern Italy of the early 20th century are well

behind us, great cites around the world still have sections of town

called “Little Italy”. By now, they are inhabited by the

grandchildren and great-grandchildren of those who left southern Italy

in such numbers that their villages of origin in the mountains of Calabria,

Puglia and Campania are, to this day, ghost towns. In Naples, today,

if you are pulled over for a traffic violation, you might be lucky enough

to have the traffic cop look at your non-Italian name, ask you where

you’re from, smile and say, “Hey, my relatives lives in

California! Say, you know, you really shouldn’t be speeding like

that on the sidewalk outside a major hospital. Well, run along. Just

be careful.” Emigration

occupies a good deal of space in the collective psyche of southern Italy.

Everyone seems to have a brother, cousin or uncle who has gone away

to find work and never come back. Indeed, even though the great waves

of emigration from southern Italy of the early 20th century are well

behind us, great cites around the world still have sections of town

called “Little Italy”. By now, they are inhabited by the

grandchildren and great-grandchildren of those who left southern Italy

in such numbers that their villages of origin in the mountains of Calabria,

Puglia and Campania are, to this day, ghost towns. In Naples, today,

if you are pulled over for a traffic violation, you might be lucky enough

to have the traffic cop look at your non-Italian name, ask you where

you’re from, smile and say, “Hey, my relatives lives in

California! Say, you know, you really shouldn’t be speeding like

that on the sidewalk outside a major hospital. Well, run along. Just

be careful.”

It is difficult

to leave home, and, for whatever reason, it is very difficult for Neapolitans.

The 1925 tear-jerker evergreen of the emigrant Neapolitan song is “Lacreme

napulitane”. It is in the form of a letter from America, written

home by a son to “dear mother” in Naples. It is a lament

of how difficult it is to be far from home, away from the sound of the

zampogna, (the Neapolitan bagpipes, traditional at Christmas),

and away from the “sky of Naples”. The refrain starts with

the cry, “How many tears America has cost us” and ends with

“How bitter is this bread”.

Today,

generations after emigration took southern Italians over the seas, there

has arisen a different kind of “emigration,” one within

Italy, itself. It strikes non-Italians as strange, but Neapolitans or

Sicilians who moves to Milano for a job—as so many of them have

done since the Italian “economic miracle” of the 1950s and

60s, will often say that they have “emigrated,” using the

exact same terminology they would if they had moved to New York or Frankfurt.

After all, Milan can be just as cold, foggy and foreign as those other

places—and you can barely understand the language and, Gods knows,

you sure can’t eat the food up there!

One difference

between the overseas emigration of many years ago and the newer emigration

within Italy is that many of the “new emigrants” try to

make it home as often as every weekend. Depending on exactly what northern

industrial money-machine they work at and where they live in the south,

this can mean a four or five–hundred–mile train ride, once

a week. The routine is rough: get off work on Friday afternoon, rush

down to the station, catch the overnight train (nicknamed the “Fog

Express), get off nine or ten hours later, catch up on sleep on Saturday,

spend Saturday evening and some of Sunday with the family, pile back

on the northbound train Sunday evening, get into their northern destination

early Monday and rush to work without really having slept on the train.

Sleeping

berths and express trains generally cost more than the average worker

will be able to spend every week; even the bare-bones second-class seat

runs 60 euros for a return ticket. Two-hundred and fifty dollars a months

is too steep for some, and the word among the “commuter emigrants”

at the station is that if you jump in the last car and stand in the

corridor all night, the conductor is a pretty good guy and may just

not notice that you have no ticket—after all, he knows you’re

just trying to get home to see your kids.

A few manage

to grind out the miles like this, week in and week out. Very few manage

to last, year in and year out. The turnover is enormous; that is, every

month, 35 out of 100 southern workers in northern Italy will quit, to

be replaced by other commuters, who presumably will last a while and

then, in turn, call it quits themselves.

Northern

League, the

I

see that they put on Verdi’s The Battle of Legnano at San

Carlo the other night for the first time in 142 years. He wrote it in

1849. If it was, indeed, performed in 1861 in Naples, I suspect it must

have been some sort of revolutionary musical salute to the then recent

defeat of the Bourbons and the incorporation of the Kingdom of Naples

into the Kingdom of Italy. (I am not driven by my scholarly demons to

the point of actually finding a concert program from the other night

to see if I have guessed correctly.) That battle, by the way, took place

in May of 1176 between the Lombard League and the forces of emperor

Frederick Barbarossa. Legnano is just a short hop up the A8 autostrada

from Milano (see map 19, coordinate B6 in the fabled 1995 edition of

the Italian Auto Club book, On the Road with ACI.) If you get

confused and wind up in Legnago, then you are way over to the east near

Verona and are hopelessly lost. There is no evidence that this is what

happened to Frederick Barbarossa, but he did lose the battle. And no

one ever wrote an opera about Legnago—though, for the sake of

completeness, I should point out that in 1879 Giosuè Carducci

wrote a poem entitled Song of Legnano, in which he shows no sign

of being confused at all. I

see that they put on Verdi’s The Battle of Legnano at San

Carlo the other night for the first time in 142 years. He wrote it in

1849. If it was, indeed, performed in 1861 in Naples, I suspect it must

have been some sort of revolutionary musical salute to the then recent

defeat of the Bourbons and the incorporation of the Kingdom of Naples

into the Kingdom of Italy. (I am not driven by my scholarly demons to

the point of actually finding a concert program from the other night

to see if I have guessed correctly.) That battle, by the way, took place

in May of 1176 between the Lombard League and the forces of emperor

Frederick Barbarossa. Legnano is just a short hop up the A8 autostrada

from Milano (see map 19, coordinate B6 in the fabled 1995 edition of

the Italian Auto Club book, On the Road with ACI.) If you get

confused and wind up in Legnago, then you are way over to the east near

Verona and are hopelessly lost. There is no evidence that this is what

happened to Frederick Barbarossa, but he did lose the battle. And no

one ever wrote an opera about Legnago—though, for the sake of

completeness, I should point out that in 1879 Giosuè Carducci

wrote a poem entitled Song of Legnano, in which he shows no sign

of being confused at all.

In any

event, the modern Northern League (anti-Federalists who have recently

pulled in their horns a bit on calling themselves “secessionists”*)

call their “nation” Padania (from the Latin adjective for

the Padus river, the Po, in modern Italian) and every year have a party

congress in Legnano to reminisce about the good old days when central

government (Imperial authority) got their cavalry kicked by the locals.

Barbarossa’s grandson, Frederick II, however, soon strode upon

the scene and put Imperial matters right.

(There

is a separate entry about Frederick II.)

(*Not

too long ago, a young flight attendant for Alitalia got herself in trouble—just

as the plane was about to land in Milano—by welcoming passengers

to “the capital of Padania”.)

Cell-phones

(1)

It

used to be that when you saw someone talking to himself on the street,

that was really what he was doing—talking to himself or perhaps

to the Mother Ship. He was just some poor soul “from Aversa,”

as they used to say around here, Aversa (north of Naples) being the

site of the now defunct hospital for the criminally insane. It

used to be that when you saw someone talking to himself on the street,

that was really what he was doing—talking to himself or perhaps

to the Mother Ship. He was just some poor soul “from Aversa,”

as they used to say around here, Aversa (north of Naples) being the

site of the now defunct hospital for the criminally insane.

No more.

The hands-off cellular phone has arrived. Yes, it is still possible

that the man on the corner is channelling the disembodied voice of Artax,

Crown Prince of Atlantis (if he has a voice with a body running

around inside his head, then he is having real problems—you may

wish to stand on a different corner), but, probably, he really is

talking to someone. With that, the world's worst worst (sic) nightmare

has come true. The simply 'worst' nightmare, you will recall, is teenagers

plus telephones. You know, hours and hours of adolescent drivel clogging

the coaxials and keeping the rest of us from getting on with our own

hours and hours of adult drivel. Now, get ready for Son of Worst, to

wit: teenagers plus hands–off cell phones plus motor scooters

in Neapolitan traffic!

Something

had to happen to accommodate people like that kid on the scooter who

turned in front of me yesterday. He had—illegally—two passengers

on the back, was turning left at a busy three–way unmarked crossing

(well, 'unmarked' except for the large sign that said: "Go for it!"),

and was steering through it all with one hand only, since the other

was holding a cell phone, thus permitting him at least the potential

luxury of yakking his way into oblivion. He was also trying to smoke

a cigarette using an auxiliary tentacle that very cool teenagers miraculously

sprout for just such occasions.

I have

nothing against cell phones. I am very impressed by the self-importance

of all those global village peacocks strutting around with their electronic

status toys—into restaurants, movies, churches, shops, bars, funerals,

public restrooms and concerts. Orchestra conductors just love to hear

one ring during the closing pianissimo of, say, Tschaikovsky's sixth

symphony, and when they go off at just the right moment, they can even

heighten the fulfilment of passion (—although some experts now

speculate that that might actually come more from the concussion you

get when you bolt up to answer the phone and whack your skull on the

tin roof of a Fiat 500). And now with the “call waiting”

function, you don't even need two phones to wheel and deal; with one

cell phone, you can always have "Geneva on the other line". The possibilities

are endless.

Anyway,

for that very lucky scooterman in front of me (yes, he made it through

—they always do), the main body of the hands-off voice-activated

cell phone is mounted below the handlebars and is connected by a cable

to earphones and microphone worn by the driver. The smiling young woman

in the ad for the device is, tsk-tsk, not wearing a helmet (nor were

any of the three persons on that motorscooter I missed), but the earphones

can, indeed, be mounted into a regulation noggin guard. At that point,

the ad assures, your incoming call will be totally audible, since it

is virtually sealed off from the distractions of environmental noise.

Such distractions would presumably include not only the dulcet roar

of general traffic, but the sirens of those annoying ambulances trying

to pass you, and the screams of your illegally mounted passengers as

they bounce off your scooter and are dragged with one foot in the stirrup

for a few days or until you decide to get off the damned phone.

You can,

we are assured, keep both hands on the handlebars while you talk. When

your phone rings, your "hello" or "pronto" will activate your microphone

and off you talk. The only drawback, it says in small small small print,

is that in order to dial out, you really should pull over since you

need to punch in the number manually, and you really wouldn't want to

steer with just one hand, would you? Would you?!

One moment.

I have to put you on hold. I have a call from Artax coming in.

Caves

(& tunnels & holes in the ground); streets (2)

(Honeycombing

(undermining?) the hill upon which much of Naples sits are hundreds

of caves such as the one seen in the photo, taken along the Corso Vittorio

Emanuele.)

Some

time ago I went to a restaurant at the tiny Piazzetta Leone a Mergellina,

just a block from the small Mergellina harbor. Inside, I asked for the men’s

room and followed directions the way one does—right in there,

around there, back through there. I wound up in a cave—a real

cave. It must have extended 50 yards back from the main restaurant;

it was quite high and all dug out of the hill that separates Mergellina

from Fuorigrotta. The cave was nicely fitted out with the necessary

wherewithal to keep a restaurant going: refrigerators, air-conditioning

units, storage racks, etc. And the men’s room, of course. There

were no bats—at least none that I noticed. Some

time ago I went to a restaurant at the tiny Piazzetta Leone a Mergellina,

just a block from the small Mergellina harbor. Inside, I asked for the men’s

room and followed directions the way one does—right in there,

around there, back through there. I wound up in a cave—a real

cave. It must have extended 50 yards back from the main restaurant;

it was quite high and all dug out of the hill that separates Mergellina

from Fuorigrotta. The cave was nicely fitted out with the necessary

wherewithal to keep a restaurant going: refrigerators, air-conditioning

units, storage racks, etc. And the men’s room, of course. There

were no bats—at least none that I noticed.

As it turns

out, the restaurant is only a few yards from the 700–meter Roman tunnel (popularly called “The

Neapolitan Crypt”) connecting Naples with the area beyond that

mountain, specifically, the area of Fuorigrotta, the important Roman

city of Pozzuoli, and the Imperial

port of Baia. It was built by Lucius Cocceius Aucto, one of the

great architects in the age of Augustus Caesar. He also built the other

tunnel—the “Seiano Grotto”—

two miles up from Mergellina, which burrowed beneath the Posillipo

hill for half a mile. He built another tunnel at Baia, itself, to join

the port facilities to Lake Averno. A busy man, Cocceius. Roman tunnels,

of course, no longer carry traffic, though the Fuorigrotta one was used

much later than one might think. It was actually kept up and expanded

by the Spanish and then the Bourbons in the 1700s. Coach traffic passed

through it well into the 1800s.

In 1925

and 1882-5 two modern tunnels, the “Quattro Giornate”

and the “Laziale”, respectively, were built to join

Mergellina with the north. They flank the “Neapolitan Crypt”

on either side and are heavily used today. The older one, the "Laziale,"

is so called from the adjective for "Lazio," the region where Rome is,

and the tunnel essentially has the same function as the old Seiano one—to

get traffic out of Naples and up the coast towards Rome. Back in the

main part of Naples, there is now also the Galleria della Vittoria,

built in 1927–8; this tunnel joins the center of Naples to the

areas of Chiaia and Mergellina by running from the main port beneath

Monte Echia (or Pizzofalcone), the cliff that overlooks

Santa Lucia and the Castel dell’Ovo

(the “Egg Castle”).

Most recently—opened

about 20 years ago—are the two major tunnels in the city (each

about 1 km long) that form part of the “Tangenziale”,

the road that links Naples with the main Italian autostrada network.

One passes directly beneath the Capodimonte hill and the other beneath

Vomero. There is a third tunnel as the road moves out of the main city

into the area known as the Campi Flegrei.

Tunnels

are just the start when you talk about “underground Naples”.

Sixty percent of the city, they say, “rests on nothing”.

Besides ancient tunnels, aqueducts, cisterns, and catacombs, there

are more than two-hundred (!) quarried sites in Naples—man-made

caves. They have been dug out of the hills of the city in the course

of the centuries, going back to the Greeks, who quarried the stone to

build the original city. Expansion of the city and of the city walls

continued to about the time of the fall of the Roman Empire in the 5th

century. Extensive rebuilding and expansion picked up eight centuries

later under the Angevin rule in Naples and continued well into the 1700s.

The ex-quarries

may be just a few cubic meters in volume, maybe serving as someone’s

garage or storage shed today, or they can be truly mammoth. For example,

the Spanish dug into the hill in the Chaia section of town to build

the Palazzo Cellemare in the 1560s. That man–made cavern

has found various uses through the centuries and, today, has been expanded

even further and converted into an underground seven-screen cinema.

Even larger is the space now occupied by the Augusteo cinema. The entrance

is at the bottom station of the main cable-car on via Toledo, downtown.

It covers an underground area of more than two square miles, and served

as an air–raid shelter in WW2, holding 15,000 persons. Speaking

of cable-cars, there are four of them in Naples, each with its own tunnel

to get from sea-level up to the Vomero and Posillipo sections of town

at around 500 feet; some of the time they run under open sky, but most

of the time they pass right beneath people’s homes.

Also, the

Bourbons dug out an enormous cave beneath the Palace of Capodimonte

in the 1700s. Later, the same dynasty in the 1800s built a large underground

passageway from the Royal Palace downtown along the port and under Monte

Echia to the then new barracks at Chaia. It is said to have been for

the dual purpose of moving troops into the palace area and/or moving

the royal family out in case of trouble.

There are

two older underground railway lines beneath Naples, with one new one

under construction. That makes three separate railways beneath the city

with a total number of 15 underground stations plus more on the way.

Some of the stations are very deep. The deepest and most difficult ones

to build were the ones on the Posillipo hill. It took almost 20 years

to finish them. I almost forgot: there is another underground train

line coming in from the new university and the San Paolo football stadium

in Fuorigrotta. That’s another major tunnel and four or five stations.

I have

barely scratched the surface. (You knew that one was coming.)

There is also some archaeological excavation in downtown Naples. Much

of the historic center of the city actually rests 40 feet above the

original Greco-Roman city, which was covered by a great mudslide in

the sixth century. The excavations to open the Roman market beneath

San Lorenzo took 25 years.

Not surprisingly,

in the course of the centuries, some mythology has attached itself to

the gigantic caves and tunnels of Naples. The average person in southern

Italy during the so-called “Dark Ages”—centuries before

the Renaissance—knew little about his Roman forebears and absolutely

nothing about the ancient Greeks. Who could have hollowed out all the

hillsides to produce the caves? In one example, the Roman poet Virgil was held in such high esteem in the Middle

Ages that he was reputed to have conjured the “Neapolitan Crypt”

into existence a thousand years earlier by his magical powers. Or—another

possibility—perhaps it was the Cimmerians (as in “Cimmerian

darkness”), the mythological race that Homer places near Hades

in an abode of “eternal gloom”. The Greek historian, Strabo,

as well as Roman writers such as Cicero and Pliny the Elder, place this

race of giants near Cuma, near Naples,

and tell of them carving their dwellings out of the hills in order to

hide from the light.

Finally,

in spite of engineers’ claims that much modern construction actually

reinforces the ground we live on, people around here get worried whenever

it rains a lot—as it has this week. Cave–ins are not frequent,

I suppose, but in the back of one’s mind , there is always that

metaphor about the straw that breaks the camel’s back.

Music

(3)

It

was such a good idea. I heard a beautiful baritone voice coming from

around the corner. It was slow and melancholy, but somehow I knew

it was a street vendor pitching his wares. I asked a gentleman near

me what the man was singing, and he didn’t know. I walked around

the corner, and then I saw and heard the band. It was a New Orleans-type

street band playing a slow march, and the marchers that I saw were women

dressed in 19th–century outfits. They wore high pink hats and

long dresses that brushed the ground as they walked. Many of them carried

folded parasols with them that they tapped on the ground as they walked,

as if using a cane or keeping time to the music. I thought, “A

singing street vendor with a New Orleans marching band right here in

Naples! I can’t wait to write about this.” It

was such a good idea. I heard a beautiful baritone voice coming from

around the corner. It was slow and melancholy, but somehow I knew

it was a street vendor pitching his wares. I asked a gentleman near

me what the man was singing, and he didn’t know. I walked around

the corner, and then I saw and heard the band. It was a New Orleans-type

street band playing a slow march, and the marchers that I saw were women

dressed in 19th–century outfits. They wore high pink hats and

long dresses that brushed the ground as they walked. Many of them carried

folded parasols with them that they tapped on the ground as they walked,

as if using a cane or keeping time to the music. I thought, “A

singing street vendor with a New Orleans marching band right here in

Naples! I can’t wait to write about this.”

Unfortunately,

it was a brief dream I had yesterday morning just before I woke up.

I am very upset—even saddened—by this, and I will not be

consoled at all by any load of ontological dingo's kidneys that says

maybe it was all real and what I am doing now is a dream. Save your

breath.

There are,

however, marching bands in Naples. They are parish bands and are usually

made up of not more than four or five members. They parade on the name-day

of the local patron saint. They may have a trumpet, trombone, saxophone

and bass drum, with someone holding the parish banner marching in front.

They parade in the neighborhood around the church; usually there is

someone in the ensemble whose job it is to “pass the plate”

and solicit contributions for the parish.

And, of

course, there are still singing street vendors. They no longer work

from hand–or horse–drawn carts; they drive around in those

horrible tricycle motor–buggies, screaming into microphones that

are cranked up, yea, unto feedback. If their income were a direct function

of decibels, they would be driving a Mercedes. I don’t think I

have ever met anyone who can really understand the whole pitch, sung

as it is, in an old dialect handed down from another century with the

words, themselves, distorted from the process of singing. Even my mother–in–law—then

in her 80s—told me once, “That’s the man with potatoes.”

“How

do you know?” I asked. “What’s he saying?”

“I

know from the melody. He’s probably saying something about potatoes.”

Soccer

(3)

Some

of the many books dealing with violence at soccer matches.

The term

“Hooligan” apparently derives from an English music hall

song of the 1890s describing a rowdy Irish family. It may be a variant

spelling of the family name, “Hoolihan” or “Houlihan”.

It is not clear if Mark Twain, in The Gilded Age (published in

1873), was using it in a pejorative sense in a reference in that book

to a fictitious novel he invented called The Hooligans of Hackensack.

In any case, by 1898, the word was used in the British press in its

current, generic meaning of “rowdy”. The word got a good

work-out in the form of “hooliganism” in the Soviet Union

to describe general anti-social, anti-Soviet behavior, such as loafing

on street corners and making snide comments about the next 5-year plan.

The word has been taken up into Italian (from the English use of “football

hooligans”) as a synonym for those roughnecks who show up at soccer

matches just to fight and cause trouble. It is more than a bit

hypocritical of Italians to choose a foreign term; it’s as if

they are saying, “We’re so well-behaved at sporting events

that we haven’t even got a word to describe that kind of behavior;

therefore, we cannot behave like that.” The linguistic determinism

underlying that is dubious. Belay that—it’s wrong, but don’t

get me started on the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis. The term

“Hooligan” apparently derives from an English music hall

song of the 1890s describing a rowdy Irish family. It may be a variant

spelling of the family name, “Hoolihan” or “Houlihan”.

It is not clear if Mark Twain, in The Gilded Age (published in

1873), was using it in a pejorative sense in a reference in that book

to a fictitious novel he invented called The Hooligans of Hackensack.

In any case, by 1898, the word was used in the British press in its

current, generic meaning of “rowdy”. The word got a good

work-out in the form of “hooliganism” in the Soviet Union

to describe general anti-social, anti-Soviet behavior, such as loafing

on street corners and making snide comments about the next 5-year plan.

The word has been taken up into Italian (from the English use of “football

hooligans”) as a synonym for those roughnecks who show up at soccer

matches just to fight and cause trouble. It is more than a bit

hypocritical of Italians to choose a foreign term; it’s as if

they are saying, “We’re so well-behaved at sporting events

that we haven’t even got a word to describe that kind of behavior;

therefore, we cannot behave like that.” The linguistic determinism

underlying that is dubious. Belay that—it’s wrong, but don’t

get me started on the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis.

The violence

is almost always related to the behavior of fans. They show up in masks

so police cameras can’t identify them, carry tire-irons, throw

bombs onto the field, and are so prone to violence in the stands that

police units have to be stationed strategically to keep opposing rooting

sections apart. International soccer events can be particularly egregious,

as if the fans were acting on some bizarre paraphrase of Clausewitz:

“Sports is the continuation of war by other means.” (“Maybe

we can’t invade you anymore, but just wait till I get you out

in the parking lot!”) Anyone who has ever been to a soccer

match in Naples knows that the stadium is always on the verge of boiling

over into violent behavior. Just a few weeks ago, a member of a visiting

team was stabbed by a fan in the parking lot outside the stadium after

the game. True, individual players on the field may fly off the handle

sometimes—maybe push, shove, throw a punch, make obscene gestures

to each other or even to the crowd, but that is generated by the heat

of the moment and is uncommon.

More to

the point, here, is that I don’t know of an episode of collective

hooliganism on the part of a team, itself, directed against the other

team, the fans, or, say, the referees. Maybe it just goes without saying

that adult professional players couldn’t get away with that kind

of behavior on the field. The players would certainly be expelled from

the game, and—if it really were a case of a whole team being involved—the

team could then be banned from the league.

Kids, on

the other hand, can get away with it. There are in Naples, as elsewhere

in the world, junior leagues for the young to hone their skills in a

variety of sports. There is an active youth soccer league in Naples

for 11–and 12–year–olds. The teams bear the names

of local neighborhoods in the area, and the game last week was between

Bagnolese and Virgilio. The game was apparently heading towards a 3-3

tie, when, in the closing minutes, the referee saw what he judged to

be a penalty in the area of the goal. He blew his whistle and awarded

a free kick on goal. These are a gift and almost always score.

Since these

leagues also serve to train the sports officials of the future, the

referee of the game was, himself, only 15. When he called the penalty

in favor of the home team, the members of the other team resorted to

a typical 12–year–old solution: they swarmed over and beat

him up! He had to be rescued by adult bystanders and taken home by his

mother. One adult spectator attributed this new kind of “hooliganism”

to the tendency of the media to dwell on violence in sports rather than

on the game, itself. Kids watch a lot of tv.

Stamps

Those

of us…you…who have ever reused a postage stamp or erased

a cancellation so you could reuse the stamp are criminals and will no

doubt be called to account some day. While you are serving hard time

with your fellow felons, meditate on the humbling thought that you are

a piker, a rank amateur, compared to true masters of philatelic

fraud—three of whom appeared a few years ago in the Vomero section

of Naples. I’ve just noticed that the three gentlemen mentioned

below now have their own website, so I guess they never went to jail. Those

of us…you…who have ever reused a postage stamp or erased

a cancellation so you could reuse the stamp are criminals and will no

doubt be called to account some day. While you are serving hard time

with your fellow felons, meditate on the humbling thought that you are

a piker, a rank amateur, compared to true masters of philatelic

fraud—three of whom appeared a few years ago in the Vomero section

of Naples. I’ve just noticed that the three gentlemen mentioned

below now have their own website, so I guess they never went to jail.

For an

entire year, Pierluca Sabatino, Maurizio De Fazio and Lello Padiglione

drew and lettered by computer, then used on postcards and letters,

more than 200 homemade commemorative stamps. None of the stamps were

counterfeits in the true sense of the word. That is, they were not imitations

of real Italian postage stamps. Each one of the phonies was an original

and often biting satirical comment on the times.

One stamp

showed a young hoodlum slouching against a backdrop of the Bay of Naples;

the stamp commemorated "Two Hundred Years of Organized Crime in Naples".

Another issue showed a tank rolling over a sand dune beneath the inscription,

"Finally a War!" And so on, from the commemorative of "The Week

of Putrid and Muddy Water in Naples" to the "First Exhibition of Stolen

Cars," "World Day of the Streetwalker," "Bulldozing Illegal Construction

at Mergellina," and "Don't Waste Your Life on Drugs—Steal!" each

stamp bore a message and an appropriate picture—and each stamp

was duly cancelled by the post-office and delivered to its destination.

Only once did the post-office notice; that was when the denomination

of the phony stamp didn't cover the cost of postage. The addressee had

to pay postage due.

There was

some discussion in the local media as to whether anyone in the post

office ever really noticed the stamps, or whether postal employees,

indulging their own sense of humor at the affair, just looked the other

way.

The Gang

of Three even went out of their way to get caught, always including

their real return addresses and even "issuing" special commemoratives

that read "Check Your Stamps. This Could Be a Fake!" or "First Strike

of Postal Counterfeiters." Nothing. No reaction at all. Apparently,

they got discouraged at the lack of a real challenge and blew the whistle

on themselves. At least that way, they would get some recognition. Now,

they have a website. I guess it worked.

|