©

2004 Jeff Matthews & napoli.com

Galleria

Umberto

The first architectural results

of the industrial revolution sprang up in Britain in the middle of the

19th century: Joseph Paxton's Crystal Palace in 1851, for example, and

The Oxford Museum (1859) by Deane and Woodward. By using iron, these

architects sought to reconcile the split in the Victorian personality,

which viewed such industrial material as the substance of engines to

power modern society with, perhaps, but hardly the stuff of Architecture

with a capital A -- the discipline of designing museums, hotels, universities

and other such places for the genteel to gather. The first architectural results

of the industrial revolution sprang up in Britain in the middle of the

19th century: Joseph Paxton's Crystal Palace in 1851, for example, and

The Oxford Museum (1859) by Deane and Woodward. By using iron, these

architects sought to reconcile the split in the Victorian personality,

which viewed such industrial material as the substance of engines to

power modern society with, perhaps, but hardly the stuff of Architecture

with a capital A -- the discipline of designing museums, hotels, universities

and other such places for the genteel to gather.

Such

use of glass and iron, however, was to revolutionize architecture and

eventually lead to the first steel-framed skyscrapers of the Chicago

architects before the century was out. High vaulted glass and iron domes,

governed by their own new architectural aesthetics, characterized a

number of structures built in Europe in the last decades of the nineteenth

century. The most prominent example in Naples is the Galleria Umberto

I (photo), across from San Carlo Theater.

It was inaugurated in 1890, and named for Umberto I, who was king of

Italy from 1878 until 1900 when he died at the hands of an assassin. Such

use of glass and iron, however, was to revolutionize architecture and

eventually lead to the first steel-framed skyscrapers of the Chicago

architects before the century was out. High vaulted glass and iron domes,

governed by their own new architectural aesthetics, characterized a

number of structures built in Europe in the last decades of the nineteenth

century. The most prominent example in Naples is the Galleria Umberto

I (photo), across from San Carlo Theater.

It was inaugurated in 1890, and named for Umberto I, who was king of

Italy from 1878 until 1900 when he died at the hands of an assassin.

The

idea behind the Risanamento ('resanitizing')

of Naples in the 1880s and 90s was to clear large sections of the city

that for centuries had been nests of squalid overcrowding and disease;

then rational construction could take place. The wide boulevard known

as Corso Umberto (or the Rettifilo,

the 'straight line') running from Piazza della Borsa all

the way to the main train station at Piazza Garibaldi was one result

of this effort. The Galleria Umberto was another. The

idea behind the Risanamento ('resanitizing')

of Naples in the 1880s and 90s was to clear large sections of the city

that for centuries had been nests of squalid overcrowding and disease;

then rational construction could take place. The wide boulevard known

as Corso Umberto (or the Rettifilo,

the 'straight line') running from Piazza della Borsa all

the way to the main train station at Piazza Garibaldi was one result

of this effort. The Galleria Umberto was another.

There was

a need to renew the area across from San Carlo known as Santa Brigida,

and four designs were submitted. One by Emanuele Rocco was chosen. His

plan left in place a number of historic buildings that others would

have torn down, yet presented a high and spacious cross-shaped mall,

a truly cathedralesque affair surmounted by a great glass dome braced

by 16 metal ribs. Of the four glass-vaulted wings, one fronts on via

Toledo (via Roma), still the main downtown thoroughfare, and another

opens onto the San Carlo Theater, framed like a splendid proscenium

by the portals of the gallery. The Galleria Umberto was based

on the design of the gallery in Milan completed in 1865; yet, it was

a more aesthetic fusion of the industrial glass and metal of the upper

part and the masonry below, which, itself, is a spectacular collage

of Renaissance and Baroque ornamentation, tapering off to clean smoothness

of marble at the ground concourse.

The

Gallery was built to stimulate commerce and to be a symbol of a city

reborn. It still contains numerous cafès, businesses, book and

record shops, and fashionable stores. Once it held theatres and restaurants

as well, and was, indeed, the sitting room of bourgeois Naples. Its

fate has come to be somewhat of a metaphor of Naples, meaning that there

are good times and bad, periods of splendour as well as decay. Among

its many ups and downs is even the fact that it was the target of aerial

bombardment by a dirigible in the First World War! The

Gallery was built to stimulate commerce and to be a symbol of a city

reborn. It still contains numerous cafès, businesses, book and

record shops, and fashionable stores. Once it held theatres and restaurants

as well, and was, indeed, the sitting room of bourgeois Naples. Its

fate has come to be somewhat of a metaphor of Naples, meaning that there

are good times and bad, periods of splendour as well as decay. Among

its many ups and downs is even the fact that it was the target of aerial

bombardment by a dirigible in the First World War!

These days,

you can still—and should still—marvel at the

architecture, its deceptive orderliness as it moves and shifts like

Proteus from one detail to the next. Yet, the Galleria also lets you

become for a moment the center of an equally fascinating bit of flesh-and-blood

architecture: a true human kaleidoscope swirls around you, on the way

to the opera, to work, to a rendezvous. Perhaps they are well-dressed,

perhaps dishevelled; the weird as well as the mundane, the casual and

the poised. From the perfectly nondescript to those who look like extras

in some bizarre film, they all have their own reasons for being drawn

to what is still a most remarkable structure.

d'Angri, Palazzo

The Palazzo Doria d’Angri was finished in the late

1700s by Carlo Vanvitelli, who finished the work begun by his father,

Luigi Vanvitelli. Marcantonio Doria had

commissioned the building. The building faces out onto Largo dello

Spirito Santo and is bounded on either side by via Toledo

and via Monteoliveto. Decorative work was done by many of the

same artists who worked on the great Royal Palace in Caserta. The original

owners of the building, the Doria family, assembled a vast art collection,

including works by Caravaggio. These works, in addition to numerous

porcelain pieces, clocks, carpets, etc. have been lost over the years

through auction. The Palazzo Doria d’Angri was finished in the late

1700s by Carlo Vanvitelli, who finished the work begun by his father,

Luigi Vanvitelli. Marcantonio Doria had

commissioned the building. The building faces out onto Largo dello

Spirito Santo and is bounded on either side by via Toledo

and via Monteoliveto. Decorative work was done by many of the

same artists who worked on the great Royal Palace in Caserta. The original

owners of the building, the Doria family, assembled a vast art collection,

including works by Caravaggio. These works, in addition to numerous

porcelain pieces, clocks, carpets, etc. have been lost over the years

through auction.

In more

recent times, the building and the square in front, renamed Piazza

September 7, are well known because on that date in 1860, Giuseppe

Garibaldi, after his triumphant campaign from Sicily to Naples, stepped

out onto the balcony of the Palazzo d’Angri and proclaimed

the annexation of the Kingdom of Two Sicilies (The Kingdom of Naples)

to the Kingdom of Italy, thus ending a thousand years of separate history

of southern Italy and forming the modern nation of Italy. (See The Bourbons, part 3, for more about that period

in the history of Naples.)

Herman,

volcanoes (4)

[Photo

by Herman Chanowitz; restoration by

Tana A. Churan-Davis.]

I can't

believe that Herman was holding out on me, or maybe I just didn't pay

sufficient attention when he told me of some "snapshots" he took during

WW2. I can't

believe that Herman was holding out on me, or maybe I just didn't pay

sufficient attention when he told me of some "snapshots" he took during

WW2.

Herman

is an American who has lived in Naples for many years with his Sicilian

wife. He was part of the WW2 invasion force in Salerno that fought its

way up the center of Italy, pushing the Germans back from Monte Cassino

and making its way up into Germany.

For his

efforts during the war and for all the time he has contributed as an

ambassador of good will in coordinating visits by young members of the

NATO community in Naples to various towns in the area that were directly

involved in wartime hostilities, Herman was recently made an honorary

citizen of the little town of San Pietro, not far from Cassino.

"Anyway,"

said Herman, "I have some snapshots I took in WW2."

"Oh." (Vague interest on my part.)

"I have a couple of Vesuvius."

"So do I, Herman."

"Are yours erupting?"

"As in the 1944 eruption?"

"Yup. Took'em from a Piper Club while we were flying over the eruption."

"You…were…flying…over…the…eruption…"

It took

Herman only 25 years to tell me that. It turns out that he has photos

from the North African theater all the way to the Nazi death camps.

I feel guilty about not wanting to see yet more photos of those horrors,

but I suppose I will have a look sooner or later. In the meantime, I

settled for a nice 8x10 glossy of the 1944 eruption of Mt. Vesuvius.

It has the classic dense column of smoke billowing thousands of feet

above the mountain. I am sure there are other photos like it, but this

one is mine.

Yiddish

(2), pizza (2)

The

last few months have seen the growth of some good give–away morning

newspapers in Naples. One of them is City Napoli. It has three

pages of international news, a couple of pages of features and human

interest, a page or two on Naples news, a sports page and, of course,

a lot of advertising, which pays for the enterprise. The

last few months have seen the growth of some good give–away morning

newspapers in Naples. One of them is City Napoli. It has three

pages of international news, a couple of pages of features and human

interest, a page or two on Naples news, a sports page and, of course,

a lot of advertising, which pays for the enterprise.

This morning

there is a human interest story on the front page for a change. There

is a photo, taken in Portland, Oregon of a young man and woman—"street

people"— sitting on their bags on the sidewalk. One of them is

holding up a sign that says: "Pizza Schmizza paid me to hold this sign

instead of asking for money". The caption above the photo says: "The

Homeless. New frontiers in advertising". The paragraph below says, simply,

that the kids are paid only in pizza and soft-drinks, and that this

seems to be a new record in aggressive advertising. Reading between

the lines, they mean, I think, "a new low in advertising".

The reason

it was on the front page of a Neapolitan paper, no doubt, has to do

with the pizza. Neapolitans are always concerned that the rest of the

world is doing something wrong, clumsy, and unorthodox—with an

outright potential for true evil—with the real Neapolitan product.

My wife's comment upon eating a Taco Pizza in Honolulu pretty much sums

it up: "This is pretty good, but they should call it something else.

It's not pizza."

I ran into

a young Japanese cook in Naples a few weeks ago. He didn't speak a word

of Italian, but his sponsors in Kagoshima, Japan, had sent him to Naples

with an interpreter (!) to learn how to make real pizza and bring home

the bacon (not an authentic topping, by the way) to Japan where

he will strut his stuff in a genuine Neapolitan pizza place in Kagoshima.

That city and Naples have one of these strange "sister city" deals going.

There is also a street named "via Kagoshima" in Naples (see here). There may very well be young Neapolitan

cooks running around Kagoshima at this very moment with their interpreters,

learning how to make sushi and fugu, the infamous poisonous

puffer or blowfish of the family Tetraodontidae, class Osteichthyes,

and order Tetraodontiformes, the body of which contains a toxin

1250 times more powerful than cyanide, one serving of which costs $200,

and even a slightly imperfect preparation of which will kill you in

no time flat. There are no Japanese restaurants in Naples, and that

reassures me.

What the

paper didn't explain—and what the proprietor of my local morning

coffee bar wanted to know—was the name of the restaurant, "Pizza

Schmizza".

"Maybe

it's Neapolitan Yiddish," I said.

That didn't

do any good, since not even Neapolitan Jews speak or know anything about

Yiddish (see here).

"OK, then

it's a Yiddish example of what is called—depending on the context—

'echo-word reduplication,' 'linguistic doubling,' 'rhyming reduplication'

and, at linguistics department beer-parties, 'phonesthemic doubling'.

Some examples in English are drinky-winky, harum-scarum, helter-skelter,

higgledy-piggledy, and in so-called Cockney Rhyming Slang, 'loaf' for

'head' (since 'loaf of bread' rhymes with 'head'). Yiddish uses the

sound 'schm—' as the PSDA (Phonesthemic Secret Double Agent)

for humorous effect."

"Oh."

"So how about some coffee," I said.

"Coffee-schmoffee. How about you should pay me for yesterday morning

already."

Sant'Eligio

The French Gothic church of Sant’Eligio was built

during the reign of Charles of Anjou by the same congregation that built

the nearby Sant’Eligio hospital in 1270. It is the first church

built in Naples by the Angevin French. Little remains of the original

structure. The arched passageway that opens onto Piazza Mercato

(Market Square) is through the original façade of the church

and has since been incorporated into the structure of the ancient hospital. The French Gothic church of Sant’Eligio was built

during the reign of Charles of Anjou by the same congregation that built

the nearby Sant’Eligio hospital in 1270. It is the first church

built in Naples by the Angevin French. Little remains of the original

structure. The arched passageway that opens onto Piazza Mercato

(Market Square) is through the original façade of the church

and has since been incorporated into the structure of the ancient hospital.

Many of

the lines of the original structure came to light only in the course

of restoration after the bombardments of the WWII.

Much of the painted ornamentation adorning the church only goes back

to the great urban renewal of Naples in the last years of the 19th century.

Sant’Eligio and a number other Gothic structures in the area were

restored in this fashion.

It is interesting

to me how—in the long history of a city such as Naples—the

center of town shifts over the centuries. The Church of Sant'Eligio,

at one time, opened onto the most important part of the city, Piazza

Mercato (see here and here).

Here is where crowds gathered, where revolutions started, and where

public executions were held. It is, today, anonymous and totally ignored,

having been cut off from the rest of the city by the contructions of

the risanamento, the urban renewal

of Naples in the late 19th century. It is also adjacent to the entry

to the industrial port of Naples and, as such, was heavily bombed in

WW2. It is a mile removed from where the great cruise liners disgorge

tourists and money into the new center of town, Piazza Municipio.

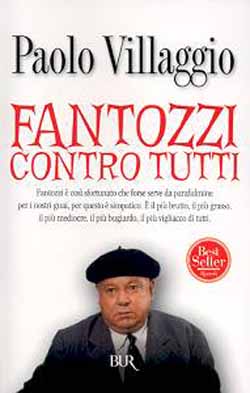

Petty

theft (1)

Getting

mugged is funny only in the movies. The best scene along those lines

in Italian cinema is probably from the 1988 film Fantozzi va in pensione

(Fantozzi Retires) with Paolo Villaggio. Villaggio (b. 1938) is a Genovese

actor/comic who has created the character of Ugo Fantozzi, a good-natured,

bumbling, and thoroughly mediocre bureaucrat who can do nothing right

and whom everyone takes advantage of. Villaggio brought Fantozzi to

life in a 1975 film; through the year 2000, ten films appeared. Some

critics have called the character the most original comic "mask" in

Italian cinema since Totò. Physically, Villaggio recalls

the American comic, Lou Costello, and the character of Fantozzi has

become a metaphor in modern Italy of the inept and put-upon Everyman

much in the same way as "Walter Mitty" or, more recently, "Dilbert,"

in the United States. Getting

mugged is funny only in the movies. The best scene along those lines

in Italian cinema is probably from the 1988 film Fantozzi va in pensione

(Fantozzi Retires) with Paolo Villaggio. Villaggio (b. 1938) is a Genovese

actor/comic who has created the character of Ugo Fantozzi, a good-natured,

bumbling, and thoroughly mediocre bureaucrat who can do nothing right

and whom everyone takes advantage of. Villaggio brought Fantozzi to

life in a 1975 film; through the year 2000, ten films appeared. Some

critics have called the character the most original comic "mask" in

Italian cinema since Totò. Physically, Villaggio recalls

the American comic, Lou Costello, and the character of Fantozzi has

become a metaphor in modern Italy of the inept and put-upon Everyman

much in the same way as "Walter Mitty" or, more recently, "Dilbert,"

in the United States.

In the

scene in question, Fantozzi is picking up his first pension check at

the post-office. Outside, of course, the hit-and-run petty thieves on

motorbikes are waiting, except that in this comic version they are all

waiting in an orderly line, each having taken one of those proper customer-service

numbers from a dispenser at the entrance to the thief staging area.

When Fantozzi gets his money and heads for the exit, the thief overseer

calls out to his charges, "OK, number 32 has left the window. Who has

32?" Two punks obediently raise their hands, and they are then

the ones who roar by and rip Fantozzi's pay envelope from his hand as

he leaves the post-office. If you don't find that funny, maybe you had

to be there—or maybe you have been mugged, yourself.

There was

certainly nothing funny about it in Naples the other day for Hari Ahuwalia,

a gentleman from India in town to sign a "sister city" pact between

his city of Calcutta and Naples. In 1992 Mr. Ahuwalia was on the first

Indian expedition to Mt. Everest. Also, he was wounded more recently

in an India/Pakistan border clash, as a result of which he is confined

to a wheel-chair. He was sitting outside of the Villa Pignatelli

on the Riviera di Chiaia, a popular tourist attraction in the

city these days. He was, perhaps foolishly, wearing a Rolex watch. He

was assaulted by two young thieves who took his watch and sped off.

The city was not pleased.

It is true

that he got his watch back, but not—as one paper reported—because

the thieves "repented". That lends an undeserved Robin Hood flavor to

the episode. What apparently happened was that bad "good guys"—very

tough plainclothes cops—went into the Spanish Quarter of Naples,

where they know many of these petty thieves hole up and threatened to

sit on the place forever. They can micro-harass an entire neighborhood

to death—confiscate motorbikes, ticket people for not wearing

safety helmets, for not having their "papers" in order, for littering,

for jaywalking, etc. The next day, the cops got the phone call they

were waiting for: the watch is in a bag at such-and-such a corner. The

retrieved it, and an agent flew to the Milan airport to return it to

Mr. Ahuwalia just as he was about to leave for home.

Filangieri

Museum

Many things are not what they used to be, but the building housing

the Filangieri Civic Museum, on via Duomo, is not even where

it used to be! It was built between 1464 and 1490 by Tuscan artisans

at the behest of the wealthy Neapolitan merchant, Angelo Como, a favorite

at the Aragonese court. The building is, thus, in the style of the Florentine

Renaissance and is known as Palazzo Como. It was sold in 1587 and was

incorporated into an adjacent monastery. Many things are not what they used to be, but the building housing

the Filangieri Civic Museum, on via Duomo, is not even where

it used to be! It was built between 1464 and 1490 by Tuscan artisans

at the behest of the wealthy Neapolitan merchant, Angelo Como, a favorite

at the Aragonese court. The building is, thus, in the style of the Florentine

Renaissance and is known as Palazzo Como. It was sold in 1587 and was

incorporated into an adjacent monastery.

In 1881-82,

because of the demolition and construction going on during the

urban renewal of Naples (called, in Italian,

the ‘Risanamento’ —literally, ‘restoring to

health’), it was necessary to dismantle the entire building stone

by stone and move it back some 20 meters so that via Duomo could be

widened. Since that date, the building has housed the museum donated

by Gaetano Filangieri, prince of Satriano (not to be confused with his

homonymous grandfather—see here.)

Though

parts of the collection were destroyed in aerial bombardments in WW

II, the museum still displays an impressive assortment of arms, porcelain

and period costumes. Additionally, there is the recent addition of a

large table-top scale wooden model of the city of Naples as it existed

during the Spanish viceroyship.

At this

writing, the museum is closed for repairs as well as the construction

going on for the via Duomo station of the new Naples Metropolitana.

Many of the museums exhibits are temporarily on display in the Maschio Angioino.

Vergil

(2)

Across the street from the Mergellina train station is an

historical park known as The Tomb of Virgil,

the traditional last resting place of this immortal Roman poet, who

spent much of his life in the city of Naples. Legend says that

the poet—also renowned as a sorcerer—called

the tunnel into existence by his powers. (It may also have been Lucius

Cocceus Auctus, the great Roman engineer who built the nearby Seiano

Grotto and many of the fortifications of the Roman

Imperial Port in Baia.) Across the street from the Mergellina train station is an

historical park known as The Tomb of Virgil,

the traditional last resting place of this immortal Roman poet, who

spent much of his life in the city of Naples. Legend says that

the poet—also renowned as a sorcerer—called

the tunnel into existence by his powers. (It may also have been Lucius

Cocceus Auctus, the great Roman engineer who built the nearby Seiano

Grotto and many of the fortifications of the Roman

Imperial Port in Baia.)

Also, whether

or not the author of The Aeneid is actually buried here, another,

much more recent, poet is: the most famous of all Italian Romantics,

Giacomo Leopardi, who died in Naples in 1837. From within the park,

itself, you have a view of the entrance to a tunnel built by the Romans

in the second century B.C. to connect Naples and Pozzuoli.

This is

the tunnel, or ‘grotta,’ referred to in the name of this

area of the city, Piedigrotta—"at

the foot of the grotto". This tunnel was used on and off until well

into the 19th century before being superseded by the two modern tunnels

used by the traffic of today.

Archaeology (3)—

Uncovering

the "Little Venice" near Poggiomarino

Naples

and the adjacent area near Mt. Vesuvius are always the stage for conflict

between antiquity and progress. Which do we need more, new metro stations

so people can move around the city more easily, or those original Greek

walls of the city now buried down there where those shiny new trains

would like to run? You get various answers depending on whom you

ask and how you phrase the question. I remember when they restored the

grimy and weathered stone of the Aragonese Victory Arch over the entrance

to the Angevin Fortress some years ago. The arch looked good when they

finished it, and it managed to keep its new complexion, oh, for a number

of days until it was defaced by eggshell grenades maliciously filled

with red ink. The missiles were tossed not by random vandals, but by

those making a political statement that the city spends too much on

the past and not enough on the present. Naples

and the adjacent area near Mt. Vesuvius are always the stage for conflict

between antiquity and progress. Which do we need more, new metro stations

so people can move around the city more easily, or those original Greek

walls of the city now buried down there where those shiny new trains

would like to run? You get various answers depending on whom you

ask and how you phrase the question. I remember when they restored the

grimy and weathered stone of the Aragonese Victory Arch over the entrance

to the Angevin Fortress some years ago. The arch looked good when they

finished it, and it managed to keep its new complexion, oh, for a number

of days until it was defaced by eggshell grenades maliciously filled

with red ink. The missiles were tossed not by random vandals, but by

those making a political statement that the city spends too much on

the past and not enough on the present.

A similar

conflict is being played out in the town of Poggiomarino, on the Sarno

river, not far from Pompei. The Sarno river is, one reads, the most

polluted river in Europe. That is staggering. What the area needs—besides

a powerful environmental patron demon who kills polluters right on the

spot—is a water purification facility placed at a strategic point

far enough inland so that the populace between that point and Torre

Annunziata on the coast no longer have to live on the banks of a

toilet and such that the water that reaches the Mediterranean Sea is

clean. Poggiomarino was to be the site for such a facility.

Then, in

October 2000, a significant archaeological discovery was made while

construction of the new purification plant, itself, was underway. The

site is already being called "little Venice" by archaeologists (in the

same way, I suppose, as they refer to the prehistoric village in Nola

as a "Bronze Age Pompeii" [see here]—maybe

it helps drum up support). To wit: a 20–acre Bronze Age settlement,

inhabited between 1700 and 700 b.c. Ancient engineers ingeniously drained

a large swamp to their advantage, creating raised artificial islands

of wooden pilings for their homes and using the waters of the Sarno

river to feed a system of canals—which is where the "little Venice"

part comes in. Hundreds of thousands of ceramic shards have been found,

as well as hundreds of items of wood, bronze, glass, amber, iron, and

wrought bone and animal horn.

Such

"pile-dwellings" are more commonly associated with the remains of primeval

villages in the Alps and pre-alpine regions. This one in Poggiomarino

is the only example, thus far discovered, of such a settlement in southern

Italy. Speculation is rampant: Who were they? Why did they leave? Were

they pushed out by the early encroachers of Magna

Grecia? Are these the people who moved a short distance away and

built the settlement that would grow into Roman Pompeii some centuries

later? The site is so significant that there is already talk of a Prehistory

Park in the area. That is very ambitious. In any event, work on the

water purification facility has stopped. It will have to be built elsewhere—but

it certainly has to be built.

Bruni,

Sergio

It

has been a bad year for the Neapolitan Song. In March, Roberto Murolo passed away, and the day before yesterday

it was the turn of Sergio Bruni. He was 82. Services will be held today

in the "artists' church," the Church of San

Ferdinando, across from the Royal Palace. It

has been a bad year for the Neapolitan Song. In March, Roberto Murolo passed away, and the day before yesterday

it was the turn of Sergio Bruni. He was 82. Services will be held today

in the "artists' church," the Church of San

Ferdinando, across from the Royal Palace.

Bruni was

praised in the pages of il Mattino, the Neapolitan daily, by

Roberto De Simone, musicologist and

the authority on anything musical having do with Naples, from opera

to folk and pop music to—in this case—the Neapolitan

Song. De Simone recalls that playwright Eduardo

de Filippo once called Bruni "the voice of Naples," a title that

stuck, as did De Simone's own reference to Bruni as an "aristocrat from

the people". Bruni, in fact, was born poor in Villaricca, a town near

Naples, and started his life in music by learning to play the clarinet

for the town band. Sergio Bruni was a stage name; his real name was

Guglielmo Chianese.

Though

perhaps not the academic anthologist of music that Murolo was, his active

career as a singer spanned more than three decades, starting in the

1950s, and—with Murolo— Bruni enjoyed the reputation of

one of those performers who helped the Neapolitan Song survive the onslaught

of American popular music at mid-century. He was a dedicated opponent

of the napolesi, as he called them (using a non-word instead

of the standard adjective, napoletani to describe the false

quality that he detested), those purveyors of commercial "Neapolitan-ness,"

the hawkers of 'o sole mio. When, some years ago, the Italian

state television network, RAI, pulled the plug on its Festival of Neapolitan

Song, Bruni said that he and his friends popped open four bottles of

champagne to celebrate. And when he read a music maven's complaint in

1975 that the "true" Neapolitan song was dead, he teamed up with noted

Neapolitan poet Salvatore Palomba to write the haunting Carmela,

now a classic and one of the best-loved of all Neapolitan

songs.

In the

1970s he again worked with Palomba in a television production entitled

"Unmask Pulcinella," noted—as the title might imply—for

its lack of sentimentality about Naples, the "land of sun", yes, but

also the land that hundreds of thousands of emigrants had deserted earlier

in the century in order to find a better life. In such work, it is fair

to regard Bruni as a forerunner of more recent singer/songwriters such

as Pino Daniele and others, whose music is often a litany of what has

gone wrong with Naples.

Bruni was

both a Communist and a devout Roman Catholic, one, they say, who would

read the Bible before dinner and Che Guevarra at bedtime. He was an

active participant in the popular uprising against German troops in

the city in 1944, an episode known as "The

Four Days of Naples". His other activities included, for example,

a brief appearance as a hotel musician in Billy Wilder's delightful

1972 film, Avanti .

Serra

di Cassano, Palazzo

The Palazzo Serra di Cassano is up from and behind

Piazza Plebiscito on via Monte di Dio, the road leading

up to the height of Pizzofalcone. It is from the first half of the 1700s

and to this day represents the finest in the tradition of Neapolitan

urban architecture. It was built by Ferdinando Sanfelice, also responsible

for the construction of the nearby Nunziatella,

the military academy in the days of the Bourbons. The Palazzo Serra di Cassano is up from and behind

Piazza Plebiscito on via Monte di Dio, the road leading

up to the height of Pizzofalcone. It is from the first half of the 1700s

and to this day represents the finest in the tradition of Neapolitan

urban architecture. It was built by Ferdinando Sanfelice, also responsible

for the construction of the nearby Nunziatella,

the military academy in the days of the Bourbons.

The building

is vast, originally having entrances on two different streets; the one

that used to open onto via Egiziaca facing the Royal Palace was

closed many years ago, however, in 1799 when the owner closed it to

protest the execution of his son, said to be involved in revolutionary

activities of the day. He said the door would remain closed until the

ideals for which his son died were realized. It is still closed. The

dual portals of the entrance on via Monte di Dio open onto

twin curved stairways (photo) leading up over an octagonal courtyard.

The elegance of the decoration, chandeliers, inlaid marble, etc. make

the Palazzo Serra di Cassano a paragon of regal Bourbon residences.

Today it houses the Italian Institute for Philosophical Studies.

Pazzariello;

Marotta, G. (3)

I have heard that the pazzariello still exists,

but I have never seen one except in a period re-enactment of the Naples

of days gone by. Indeed, in April 1997, RAI, the Italian state radio,

ran a short program called "The Last Pazzariello of Naples" in which

they went to a hospital in the Spanish Quarter and talked to Michele

Lauri, born in 1920, the gentleman purported to be the last of his kind

except, as I say, in re-enactments. (Also see

here.) "Don Michele" said he had plied his trade from the end of

WWII until the late 1980s—50 years of being a pazzariello,

then, eventually, the last one in Naples. For many centuries, before

mass printing and then electronics made it so much easier to spread

the word, there was a profession called "town crier" or some variation

thereof—a person paid to walk around and shout out the news of

the day and also get in a few ads for local merchants. The pazzariello

was that person in Naples. I have heard that the pazzariello still exists,

but I have never seen one except in a period re-enactment of the Naples

of days gone by. Indeed, in April 1997, RAI, the Italian state radio,

ran a short program called "The Last Pazzariello of Naples" in which

they went to a hospital in the Spanish Quarter and talked to Michele

Lauri, born in 1920, the gentleman purported to be the last of his kind

except, as I say, in re-enactments. (Also see

here.) "Don Michele" said he had plied his trade from the end of

WWII until the late 1980s—50 years of being a pazzariello,

then, eventually, the last one in Naples. For many centuries, before

mass printing and then electronics made it so much easier to spread

the word, there was a profession called "town crier" or some variation

thereof—a person paid to walk around and shout out the news of

the day and also get in a few ads for local merchants. The pazzariello

was that person in Naples.

Typically,

he dressed in mock military garb—a homemade uniform with bizarre

medals, epaulets and a diagonal sash across the chest. He wore a fancy

French Bourbon tricorn hat, usually with the points at front and back

instead of on the side and carried a large baton. He looked perhaps

more like a circus ringmaster than a general, but at least it was conspicuous.

The pazzariello (from the Neapolitan verb pazziare—to

joke) was usually accompanied by a small band of at least a flautist

and a bass-drum. He paraded around the streets and announced that a

new shop was opening, or that this or that shop was almost giving away

merchandise, so hurry, hurry, hurry—or that so-and-so had lost

a wedding ring and would the finder please have it in his heart to return

it. He told a few jokes, rhymed a few couplets, and there were also

the obligatory bits of gossip and anti-establishment comments. He and

his small entourage picked up the few coins that people tossed their

way.

If the

pazzariello is familiar at all to those outside of Italy, it

is probably through the 1954 film, L'oro di Napoli (The Gold

of Naples), directed by Vittorio De Sica (1901-74). The film consists

of five episodes (six in the US release) based on those found in the

1947 book of the same name by Giuseppe Marotta (1902-1963). The first

episode in the film (il guappo—the Racketeer) revolves

around the character of a pazzariello, played by the great Totò

(See photo, above). (Don Michele, the real deal, had a bit part in the

film and was a technical advisor.) Totò's performance is uncharacteristically

dark and melancholy and the episode has been called by one critic the

last bit of true "neorealism" to come from De Sica (the director of

The Bicycle Thief and Umberto D) before he started making

more light-hearted fare.

[Click

here for an item about another story in the book, The Gold of

Naples, an episode that was not in the film. Also

here for an episode from both book and film.]

Capri

(1)

| Capri,

looking down down from Monte Solaro to the Villa Tiberius and, in

the background, the tip of the Sorrentine Peninsula. |

Capri

first attracted real and royal attention when Caesar Augustus

dropped by in 29 B.C. He liked it so much that he traded Ischia for

it. Since that time, there has been an unbroken chain of Capri admirers,

from the Longobards to the Normans,

Angevins, Spanish, Austrians, English

and modern Italians. All this attention is understandable. Of the islands

in the Bay of Naples, Capri simply has the most to offer. It is geologically

spectacular, from its two high points, Monte Solaro and Monte

Tiberius, rising like pillars at opposite ends of the island, to

natural wonders such as the Blue Grotto and the twin rocks known as

the faraglioni jutting up from the waters just off the east end

of the island. Capri

first attracted real and royal attention when Caesar Augustus

dropped by in 29 B.C. He liked it so much that he traded Ischia for

it. Since that time, there has been an unbroken chain of Capri admirers,

from the Longobards to the Normans,

Angevins, Spanish, Austrians, English

and modern Italians. All this attention is understandable. Of the islands

in the Bay of Naples, Capri simply has the most to offer. It is geologically

spectacular, from its two high points, Monte Solaro and Monte

Tiberius, rising like pillars at opposite ends of the island, to

natural wonders such as the Blue Grotto and the twin rocks known as

the faraglioni jutting up from the waters just off the east end

of the island.

Nowhere

in the Gulf of Naples or vicinity, not from any of the other islands,

not even from the mountains above nearby Sorrento, will you find a view

equal to that from the vantage points on Capri. (The photo shows the

view across the straits to the tip of the Sorrentine peninsula.) Its

manmade attractions are also hard to beat: an old Saracen

tower on Mt. Barbarossa, the cliffside path named via Krupp,

a hermitage, a monastery, and the most serene chairlift you will find

anywhere, leading from the town of Anacapri up to the top of Monte Solaro. Additionally,

you can hike, hang-glide, scuba-dive, go down in a submarine, shop till

you drop, and then relax with all the other "beautiful people" at an

open-air cafe in one of the most famous squares of its kind in the world.

So, even if, unlike Tiberius, you never get to "relax with equal application

into secret indulgences and immoral pastimes," you can still rely on

having a good time if you follow some simple rules. Nowhere

in the Gulf of Naples or vicinity, not from any of the other islands,

not even from the mountains above nearby Sorrento, will you find a view

equal to that from the vantage points on Capri. (The photo shows the

view across the straits to the tip of the Sorrentine peninsula.) Its

manmade attractions are also hard to beat: an old Saracen

tower on Mt. Barbarossa, the cliffside path named via Krupp,

a hermitage, a monastery, and the most serene chairlift you will find

anywhere, leading from the town of Anacapri up to the top of Monte Solaro. Additionally,

you can hike, hang-glide, scuba-dive, go down in a submarine, shop till

you drop, and then relax with all the other "beautiful people" at an

open-air cafe in one of the most famous squares of its kind in the world.

So, even if, unlike Tiberius, you never get to "relax with equal application

into secret indulgences and immoral pastimes," you can still rely on

having a good time if you follow some simple rules.

First,

pronounce it CAH-pri, not cuh-PRI. This is essential to the enjoyment

of your stay, since this common tourist mispronunciation of the name

of the island sounds just like a local dialect expression meaning, "Please,

I would like to give you some more of my money."

Next,

if you have the time—and if you haven't, maybe you shouldn't

go—enjoy a ferry trip from the main port downtown, at least one-way.

Hydrofoils are great, but so are open-air sea trips. In the warm summer

months, you can also take a marvelous detour by ferry over to Sorrento

and then back to Naples. If you have a choice, go on a week-day, not

a week-end, although in the peak season, there may not be much difference.

Fortunately, since the island is virtually a web of footpaths, you will

be free to take advantage of the fact that most tourists don't really

like to walk. You can find solitude on Capri, even in the high season.

Prepare

an itinerary that says:

(a)

Blue Grotto

(b)

The Villa of Tiberius

(c)

The Villa of Axel Munthe

(d)

Monte Solaro

(e)

Afternoon free for shopping

Then take

a small hammer, which you should always keep with you for such occasions,

and rap yourself soundly in the skull to cure yourself of the notion

that it is possible to do it all in one day. Relax.

Divide

the island, for touring purposes, into two parts, and then decide on

one or the other for your visit. The two parts are Capri and Anacapri.

Capri includes the delightful little main square in the town of Capri,

itself, and everything leading out towards the eastern height of the

island and the villa of Tiberius. It might also include going down the

via Krupp pathway to the north side of the island and the Marina

Piccola (small harbor). Divide

the island, for touring purposes, into two parts, and then decide on

one or the other for your visit. The two parts are Capri and Anacapri.

Capri includes the delightful little main square in the town of Capri,

itself, and everything leading out towards the eastern height of the

island and the villa of Tiberius. It might also include going down the

via Krupp pathway to the north side of the island and the Marina

Piccola (small harbor).

The Anacapri

side of the tour includes the town of Anacapri, itself (quaint and less

frequented than its famous sister town) and Monte Solaro, accessible

on foot or by chair lift. If you feeling particularly energetic, you

can walk from the main port to Anacapri up the so-called "Phoenician

stairs" (that zig-zag line in the center of the photo, right.) You might

add a third part to your trip: the sea. Take a trip into the Blue Grotto,

or take a trip around the entire island. Also, undersea sightseeing

is available via a small submarine!

No private

vehicles may be taken over to Capri, but there are taxis and buses available

from the port to virtually every part of the island accessible by wheel.

Capri, however, is truly made for walking. When you disembark, avoid

the temptation to follow the crowd over to the cable car that takes

you right up to the main square in the center of the town of Capri.

Take the steps; they start a little bit past the cable-car entrance.

They are moderately strenuous, but provide a first-class view of the

picturesque houses, small gardens and paths that abound on Capri. If

you plan to go to Tiberius' Villa Jovis, the only way is to walk from

the main square, so you may wish to save yourself for that. At the Anacapri

end, treat yourself to the chairlift up and then hike down, taking in

the view and the mountain air.

Frequent

ferry and hydrofoil service is available to Capri from Naples,

from both the main port and the nearby harbor of Mergellina. Additionally,

you can get to Capri from Sorrento. If you are truly crazy, you can

get a helicopter from Capodicchino airport in Naples.

Musical

instruments

Two musical instruments closely associated with Naples

are the typical Christmas instruments, the zampogna

(bagpipe) and the ciaramella (folk oboe). Two musical instruments closely associated with Naples

are the typical Christmas instruments, the zampogna

(bagpipe) and the ciaramella (folk oboe).

Additionally,

there is, of course, the Neapolitan mandolin, a selection of which you

see in the photo on the left. The 18th-century Neapolitan mandolin

is characterized by a pear-shaped resonating chamber, an open

soundhole, and an angled top where the tuning pegs are located. The

most typical feature is the set-up of the strings: four pairs of double

strings, each pair tuned to the same note, allowing for the typical

mandolin sound, the tremolo, when struck by the plectrum. The strings

are generally tuned to g-d-a-e.

The instrument

developed in Naples in the 18th century and by now has a long history

in popular as well as classical music, including a prominent role in

Mozart's Don Giovanni (1787). The introduction of steel strings

in the mid–19th century in Naples gave the instrument a more piercing

sound particularly suited to the virtually non-existent acoustics of

outdoor performances of popular songs.

Among the

percussion instruments widely used in folk and popular music in Naples

is the so-called caccavella (upper-left in photo collage,

above). This term can often be used in a non-musical context to

mean "broken down old wreck"—for example, as applied to a car;

the instrument is also known as the putipu, onomatopoeia for

the "burping" sound the instrument makes when played. The instrument

consists of a membrane stretched across a resonating chamber, like a

drum. Instead of the membrane being stuck, however, a handle is used

to compress air rhythmically within the chamber; the air then spurts

out of the not-quite-hermetic seal that fastens the membrane to the

wooden body of the instrument. The sound is reminiscent of the sound

you get when you cup the palm of your hand into your armpit and snap

the upper arm down—(not that you would ever do such a thing).

Another

percussion instrument is the triccaballacca—a clapper—(bottom

right in photo). It has three percussive mallets mounted on a base,

the outer two of which are hinged at the base and are moved in to strike

the central piece; the rhythmic sound is produced by the clicking of

wood on wood and the simultaneous sound of the small metal disks—called

"jingles"— mounted on the instrument.

Typical

of Neapolitan folk music —and much folk music throughout Europe—is

the hand drum known as the tambourine or, in Neapolitan, tammorra.

It consists of a circular frame with a single drum head stretched

across one side of the instrument. There are generally small metal "jingles",

as with the triccaballacca, mounted around the perimeter of the

instrument, that sound as the tammorra is struck by the knuckles

or the open hand.

[These

photos were taken in the music shop of Giuseppe Miletti (the gentleman

in two of the photos) at Via S. Sebastiano 46.]

Galleria

Principe di Napoli

The Gallery Principe di Napoli, across the street from

the National Archaeological Museum, is

the galleria that nobody thinks of when you say "galleria"

in Naples, that honor being reserved for the grander Galleria

Umberto I. The Gallery Principe di Napoli, across the street from

the National Archaeological Museum, is

the galleria that nobody thinks of when you say "galleria"

in Naples, that honor being reserved for the grander Galleria

Umberto I.

The Principe

di Napoli was started in 1870 and finished in 1883. Architecturally,

it was part of the wave of urban renewal

made possible throughout Europe by the new technology of steel and glass

construction epitomized by such buildings as the Crystal Palace

in London in 1851. With its Parisian passages and Londonesque arcades

the Gallery was built to be a shopping center, or—in more modern

terms a mall.

The gallery

is slightly out of kilter because the adjacent large and untouchable

Church of Santa Maria di Costantinopoli made the construction of a logical

fourth wing impossible. There are, thus, only three entrances: from

the side of the National Museum, the Salita del Museo and the Art Academy

(the point from which this photo was taken). The Gallery was, therefore,

considered to be somewhat of an architectural flop. Neither did it enjoy

the commercial success expected. It remains, however, important as an

architectural precedent in the city, being, of course, later

overshadowed by the Galleria Umberto, built over a decade later.

Today, the Principe di Napoli houses government and private offices.

|