The mayor of Naples was shown on the screen, her eyes closed, holding up double-barrelled crossed fingers just for luck. Here it came!---"Valencia!" Boo-hiss. Disappointed mayor. Charges of favoritism. We wuz robbed. Crossed fingers swiftly converted to another hand gesture that I would not think of describing to your genteel sensitivities. The regatta, had it happened, would have meant the construction of a new, world-class boat harbor in Bagnoli. The entire area was--and remains--scheduled for rejuvenation anyway, and work has already started on that ambitious project. The ugly steel mill--an incredible piece of industrial blight--is being torn down. A new fair grounds, Science City, is already open. The regatta and boat harbor would have been a major shot in the arm, true, but work shall continue--without or without the boat race. Books about Naples

Occasionally, I get on the internet just to see what is out there in used book shops, not because I am necessarily going to buy, but I might. I have found a couple of good volumes that way about, for example, the American reaction to Garibaldi's invasion of the Kingdom of Naples, and Antonio Pace's great book, Benjamin Franklin and Italy. So, just for fun, I looked a bit today. There is nothing like a used–book store, even if it's only in cyberspace. Right off the bat, I see something I want: H.M.S. " Hannibal " at Palermo & Naples, During the Italian Revolution, 1859–1861. With Notices of Garibaldi, Francis II., & Victor Emanuel, by Admiral Rodney Mundy. London : "John Murray. 1st edition, 1863. 8vo.365pp. Frontispiece engraving & map. Some pencil annotation throughout. Inner hinges very slightly strained. Top & bottom of spine, edges & corners rubbed, original cloth lightly marked, else very good copy." Unfortunately, the price is US$233.35. I don't want it that bad. Sometimes the National Library in Naples has these things in the original English as well as an Italian translation. I'll check that one. Maybe I am setting my sights too high. Ah, $1.39! That's more like it. Let's see: Devil's Daughter, by Catherine Coulter. "New York, NY, U.S.A. 1985. Mass Market Paperback. Good. Spine lines/edge rubs/clean Tight Pgs. Book Description: Golden-haired hellion Arabella goes adventuring to Naples, Italy to solve the mystery of her father's missing ships and cargoes. But soon she discovers that the man behind the thievery is an enemy from her father's past. A man she shouldn't love, but can't resist..". Well, I'm sure it's a fine book, but I had to go to the OED just to find out what a "hellion" is—a troublesome or mischievous person. No.

As

a sheer curiosity piquer, here's one by the great Polish science-fiction

wroter, Stanislaw Lem: The Chain of Chance. London: Mandarin

Paperbacks, 1990. Softcover. Very Good. 5" x 7 3/4". Remainder stripe

on bottom of book. "...In Italy, a number of people have died mysteriously.

They tend to be foreign, male, middle-aged and to have some connection

with Naples. But there the resemblances end and even Interpol have

bemusedly closed their files. However, a former astronaut turned

private detective agrees to duplicate the exact itinerary of one

of the victims in an attempt to decipher the links in an increasingly

mystifying chain of coincidence.." 179pp." Three dollars. Mark that

one. That's a keeper, especially since "... foreign, male, middle-aged..."

reminds me of someone I know. Here's one that is actually intriguing: A woman, a man, and two kingdoms: the story of Madame d'Epinay and the Abbot Galiani, by Francis Steegmuller. Madame d'Epinay was Rousseau's patron. She set him up in a gloriously free and bucolic country estate where he could feel like a noble savage. ("Garçon, a bit more curare on my spear-point, please.") Ferdinando Galiani (1728-1787) was one of the great minds of the Neapolitan Enlightenment and the author of some important works in economics. He was also the ambassador of the Kingdom of Naples in France in the 1760s. It is entirely possible that he and madame d'Epinay had something going, but I don't know. I don't even know if I want to know. Oh, no. Here's a mistake. Even worse--it's bald-faced baloney (that's disgusting!): Marriage Italian Style, by Arnold Hano. "...Basis for spicy 1964 Sophia Loren film... whore's efforts to get longtime lover and womanizer to marry her and stay true..." That, of course, is totally wrong. The "basis for Sophia Loren's spicy 1964...etc." was the stage-play Filomena Marturano by Eduardo de Filippo. How about The Bay of Noon, by Shirley Hazard. "... NY: Picador, 2003. Trade Paperback. Near Fine/No Jacket. Reprint. 8vo - over 7¾" - 9¾" tall. 181 pp. A young Englishwoman working in Naples, Jenny comes to Italy fleeing a history that threatened to undo her. Binding tight, text clean...". I think I know that woman. Tight binding, clean text. That's her. Here it is! This is the one I want. One of the classics in its genre: Illustrated Excursions in Italy, by Edward Lear: "London: S. & I. Bentley, Wilson & Fley for Thomas M'Lean, 1846. 2 volumes, folio. (14 1/2 x 10 5/8 inches). Half-titles, 2pp. publisher's advertisments at back of vol.II. Titles with wood-engraved vignettes, 55 fine tinted lithographic views by Lear, printed by Hullmandel & Walton, 2 lithographic maps, hand-coloured in outline, 2 leaves engraved sheet music at back of vol.I, 53 wood-engraved vignettes after Lear and R. Branston. (Some spotting). Original green cloth, blocked in gilt and blind. Modern green cloth box, green morocco lettering piece. A fine complete set of Lear's magisterial record of his travels through Italy. The first volume covers Lear's tours through the Abruzzi region, 'or three Northern provinces of the kingdom of Naples' (p.1). He made three excursions between July 1843 and October 1844, recording in both words and pictures the most memorable and pictureque of the scenes he encountered. In the preface he notes that object of the work was 'the illustration of a part of Italy which.. has hitherto attracted but little attention. With the exception of [two other works].. I am not aware of any published account of the Abruzzi provinces in English; and the drawings with which the following pages are illustrated are, I believe, the first hitherto given of a part of Central Italy as romantic as it is unfrequented' (preface). The second volume, with much briefer text than the first, includes views 'of places in the States of the Church - most of them within easy reach of visitors to Rome; yet, with the exception of Isola Farnese, Castel Fusano, and Caprarola, ..seldom seen by Tourists' (Preface). Lear notes in both volumes that the drawings 'are Lithographed by my own hand from my sketches'. And it is only $ 9,500. Here—to make that redundantly transparent—nine–thousand five–hundred dollars. I think

I'll go back and check on Jenny of the tight binding and clean text.

To

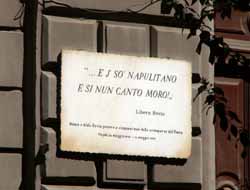

pursue his passion for dialect poetry and theater, he took odd jobs

at newspapers and then went to work in the export office of the National

Museum. He then became director of "Canzonetta," a small publishing

concern dedicated to the music of Naples. To

pursue his passion for dialect poetry and theater, he took odd jobs

at newspapers and then went to work in the export office of the National

Museum. He then became director of "Canzonetta," a small publishing

concern dedicated to the music of Naples.Oh, Don Libero—it's you! You know I have to write you up for that." "Two lire and fifty cents." "Fine," says Bovio, handing the cop a five-lire note. "Five? I can't change that." Bovio looks up at his coach-driver and says, "Get down here and take a leak. Help the officer out." Camorra, the

In

May of 1868, the journal ran an article by G.W. Appleton entitled

"The Camorra of Naples." The first paragraph was:

There follow long descriptions of the origin of the camorra, descriptions of involvement in smuggling and general leech-like attachment to all affairs public and private—what amounts to a shadow state, really. The

article is glowingly in the past tense: "…The existence until

within a few years…This society was known as the camorra…should

so long have been permitted to exist…etc." Written as it was,

not long after the unification of Italy in 1860, the article is

glowingly optimistic. It closes with this:

That, from the Ministry of "Hope springs eternal…". I can't

help wondering if this "G.W. Appleton" is, indeed, George Webb Appleton

(1845-1909), the British fiction writer. He would have been 23-years

old when he wrote the article. A good age for optimism. Cervantes in Naples Miguel de Cervantes Saarvedra (1547-1614) fled Spain in 1568 to avoid the ghastly punishment of having his hand amputated for wounding someone in a fight. He fled to Rome and a job as a domestic servant, a post he left in 1570 for the life of a common soldier. In 1571 he went aboard the Marquesa, a ship in the Holy Roman fleet and sailed from Messina to engage the Turks at the great Battle of Lepanto, one of the most important naval engagements in the history of Europe. By all accounts, Cervantes fought well; he spent the next few years in the Neapolitan vice–realm in the garrisons in Palermo and Naples. He sailed from Naples in 1575 to return to Spain and was captured by Berber pirates and held for ransom. He lived through years of hell in prison in Algiers, failing in four attempts to escape, finally being ransomed and freed in 1580. Picasso's

Don Quixote With the publication of Don Quixote, Cervantes achieved the success that had eluded him for so long. In terms of posterity, thus, he had made it, but his contemporaries were not so sure. In 1608 he was passed over for inclusion in a group of Spanish poets invited to go to Naples with the new viceroy, the Conde de Lemos. Journey to Parnassus (cited above) was the result of that snub. Cervantes had been denied the pleasure of returning to Italy, to Naples, the land of his exuberant youth, so he invited himself. That is, the long poem is written under a pseudonym, and it invites "Miguel de Cervantes" to Parnassus (Naples), the mythological home of poets and musicians. It is a somewhat tedious critique of other poets, and it is not widely read. The

place of Cervantes is now secure in the history of our literature.

He is a byword, whereas those who got that invitation are forgotten.

Cervantes is even secure against the jibe of his great contemporary,

Lope de Vega (1562-1625), who was apparently stupid enough to say

that "no one would so stupid as to praise Don Quixote." Christ Church  When

the King Ferdinand and Queen Caroline were forced to flee the city

of Naples--first by the revolution of 1799 and then by the forces

of Bonaparte in 1805--they managed to hole up and survive quite nicely

on the island of Sicily, well protected by the British fleet. Yet,

in spite of this monarchy-saving help from the English, the Bourbons

were intransigent when it came to allowing members of the Church of

England the luxury of a bit of land on which to build a church. Indeed,

the only non-Roman Catholic church in Naples was the Greek

Orthodox church, the presence of which goes back to the mid-1400s. When

the King Ferdinand and Queen Caroline were forced to flee the city

of Naples--first by the revolution of 1799 and then by the forces

of Bonaparte in 1805--they managed to hole up and survive quite nicely

on the island of Sicily, well protected by the British fleet. Yet,

in spite of this monarchy-saving help from the English, the Bourbons

were intransigent when it came to allowing members of the Church of

England the luxury of a bit of land on which to build a church. Indeed,

the only non-Roman Catholic church in Naples was the Greek

Orthodox church, the presence of which goes back to the mid-1400s.

The Bourbons, thus, denied all requests from the Anglican community in Naples for permission to build a church, both before those conflicts, as well as afterwards, when the monarchy was restored by the Conference of Vienna in 1815. For many years, the British community held church services on the premises of the British legation, housed in Palazzo Calabritto at the beginning of the Riviera di Chiaia. That

all changed in 1860 when Giuseppe Garibladi, after the conquest

of the Kingdom of Naples by forces under his command, granted the

request and gave them the land, near Piazza San Pasquale, one block

from the Riviera di Chiaia and the Villa Comunale, the large public

gardens. The gift was--in the words of Garibaldi inscribed on a

plaque [the one in the photo, below, is not the original] on the

premises of Christ Church in Naples:

After some bureaucratic quibbling over the fact that there was already a cavalry barracks on the land, the deed was finally ratified by the Italian government on August 10, 1861. The church was to be all English: the architectural firm was Thos. Smith of Hertford and London; the stone was from Malta; and all the furniture came from England. The mosaic behind the altar, however, was by Saviati of Venice. The foundation stone was laid on December 15, 1862 and the completed church was consercrated on March 11, 1865 by the Right Reverend Dr. Sanford, first Bishop of Gibraltar. Christ Church has continued ever since--except for a break of three years during WWII--to serve the needs of the considerable English community in Naples as well as the less permanent, but sizeable, contingent of British forces from the NATO community in Naples. It also serves the American Episcopalian community. As an interesting sidelight, Garibaldi had earlier visited Britain to raise money for his campaign to invade the Kingdom of Naples. In Coventry, he is said to have planted and dedicated three oak trees with the words, "May they be struck down by lightning if ever my country declares war on this country." The story says that when Mussolini declared war on Britain some 80 years later, one of the oaks was struck. [I

have drawn some of this information from an article by Pamela

Payne that appeared in The Lion Magazine in September, 1992.

She, in turn, credited a booklet by Miss Winifred F. Allen.]

Churches—small, old, closed

Composers, other  Elsewhere

in these entries I have dealt with some prominent names in the world

of Naples and music, primarily composers from the 18th and 19th centuries

(see entries for Bellini, Cimarosa, Donizetti,

Paisiello, Pergolesi, Rossini,

and A. Scarlatti. Also see the entry,

Comic opera and Mozart). For the sake

of completeness, I should add a few more names of those who formed

what is generally called the "Neapolitan School" in the 1700s. Some

of them (in chronological order of date of birth) are: Elsewhere

in these entries I have dealt with some prominent names in the world

of Naples and music, primarily composers from the 18th and 19th centuries

(see entries for Bellini, Cimarosa, Donizetti,

Paisiello, Pergolesi, Rossini,

and A. Scarlatti. Also see the entry,

Comic opera and Mozart). For the sake

of completeness, I should add a few more names of those who formed

what is generally called the "Neapolitan School" in the 1700s. Some

of them (in chronological order of date of birth) are:Francesco

Durante 1684–1755 Francesco Durante's father was employed by the S. Onofrio conservatory, so Francesco came to his musical training at the same institution quite naturally. He then studied in Rome but returned to Naples to lead the S. Onofrio conservatory. By 1728 he was the head of another conservatory in Naples, the Neapolitan Conservatorio dei Poveri di Gesù Cristo. He served there for 10 years, resigned and then headed the Neapolitan Conservatorio di S. Maria di Loreto. (All of these various conservatories were fused into a single institution by the French when Murat ruled Naples in the early 1800s.) Durante was primarily known as a composer of sacred music and was at mid-century the most respected teacher of music in Naples. Pergolesi and Paiseiello were among his illustrious students. Anyone named Leonardo Vinci must have needed a real sense of humor. Presumably, this brought young Leo into the then new discipline of the Neapolitan Comic Opera after an education at the Conservatorio dei Poveri di Gesù Cristo. His first work was a comic opera called Lo cecato fauzo (fauzo is Neapolitan for "false"—here it is good to remember that most of these delightful works were, in fact, written in Neapolitan and not in Italian). The Blind Faker might be an appropriate translation, but I have never seen an English translation. (I have never seen the original opera, either.) It opened at the Teatro dei Fiorentini in Naples in 1719. Although his name has been historically overshadowed in the comic opera by Pergolesi and, later, Cimarosa and Paisiello, at the time—the 1720s—Vinci ruled the world of comic opera in Naples. Interestingly, his Li zite’ngalera [Old Maids in Prison] (!), from 1722, is the earliest surviving score of a Neapolitan comic opera, composed and performed well before Pergolesi's La Serva Padrona, the work that is now viewed historically as having started the great popularity of the Neapolitan musical commedia throughout Italy and elsewhere. Vinci also composed serious opera for theaters elsewhere in Italy and, indeed, was one of the musicians (besides Sarro, A. Scarlatti, and, later, Piccinni–see, below) to have a hand at writing music for Metastasio's Didone abbandonata, the work that brought literary merit back into Italian opera after decades of doggerel. Vinci died relatively young and, according to some sources, may have been poisoned as the result of an illicit love affair. [Note to myself: try to find the raw, unexpurgated version of Old Maids in Prison !] Leonardo Leo was a student at the one Neapolitan conservatory not yet mentioned in this entry, the Conservatorio S. Maria della Pietà dei Turchini and the only one that still survives as a functioning church. (See music conservatory for details of the religious origins of the Naples conservatories.) He was a successful composer and church organist by his early 20s and then turned to writing comic opera, as well. When A. Scarlatti died in 1725, Leo replaced him as the first organist of the viceregal chapel. He composed serious works for theaters in Italy as well as for the court of Spain. In Naples, in 1739, he became the head of the conservatory where he, himself, had studied. He is remembered as a teacher and an innovator, concerning himself with reforming church music as well as the orchestra of the royal opera. Somewhere, Mozart is supposed to have remarked that he wanted to compose comic opera as good as that of Niccolò Piccinni "even though I am only a German." Indeed, between 1760—the year of Piccini's first great success, the comic opera La Cecchina ossia La buona figliola (Cecchina or the Good Daughter)—and the coming of the generation of composers such as Cimarosa in the 1780s, no Italian composer was held in higher esteem throughout Europe than Piccinni. La Cecchina was the most popular work of its kind for years in Italy. The libretto is by Goldoni and is an adaptation of Pamela, or Virtue Rewarded by Samuel Richardson. Verdi, himself, said that La Cecchina was "the first true comic opera". The work belongs to the larmoyant school—"tear-jerker"—popular in the mid-1700s (and ever since?)—a young, delicate, orphaned heroine against the fates. Musically, Verdi held it in such high esteem because it was more than just a rollicking thigh-slapper; it showed Piccinni's flair for the minor, plaintif song set, uncharacteristically, in a comic piece, not unlike, say, Donizetti's later "Una furtiva lacrima" in L'elisir d'amore. There is even a virtuoso bit of angry soprano, a stylistic precursor, some say, to Mozart's "Queen of the Night" in The Magic Flute. Piccinni was a prolific composer of symphonies, sacred music, chamber music, and opera (some estimates claim he wrote as many as 300 operas). His prolificness extended to biology, as well; he had seven children and was so concerned for their wellfare and security that he accepted a well–paying appointment at the court of France in 1776. He represented one–half of the debate raging in Paris between the Italian style of music and the influential school of Gluck. Thus, it was the "Piccinnists" versus the "Gluckists," although Piccinni and Gluck, themselves, apparently never encouraged feuding between their respective claques. Piccinni returned to Naples in 1791 when the drivers of the French Revolution cut off his stipend. In Naples, he was thought to harbor revolutionary badthink and was placed under house arrest for four years. At the end of his life, he returned to France, where he died in 1800. The music conservatory in Bari, Italy—his birthplace—is named for him. Piccinni's

reputation was eclipsed—as was the entire genre of the Neapolitan

comic opera—by the subsequent shift in cultural tastes in

Europe—the outbreak of Romanticism—so perhaps this is

a good place to stop. I could have mentioned Francesco Provenzale

(1624-1704), the first Neapolitan composer of opera, very few of

whose works survive, but a great influence on the next generation;

or Niccolò Porpora (1687–1768), primarily known as

a teacher—indeed, one of Haydn's teachers and the voice teacher

of Farinelli, the great castrato. Or Niccolò Jommelli, (1714-74),

the greatest symphonic innovator of his day, whose ability to use

and even invent orchestral resources to carry text was praised by

Metastasio. Or the strange case of Johann Adolf Hasse

(1699–1783), the Austrian who came to Naples to study with

A. Scarlatti and became, I think, the only foreigner in the "Neapolitan

School" and one of Metastasio's important collaborators. The fact

that I have crammed all of these fine musicians into a single entry

as "Other Composers," is, I am aware, an injustice. It was a convenience

for me to do so and certainly reflects only upon my own limited

tastes. So, I invite you to go find a CD of Piccinni's La Cecchina,

which I have just done, and have a listen—which I have also

just done. It's fine. (I couldn't find Old Maids in Prison.)

Ferdinand IV (a sidelight) I enjoy

browsing in old journals. I mean old journals—the kind

that let you read about persons before they grow up to be "history."

Here is something I found in an issue of The North American Review

from January 1816, only the second year of existence of that distinguished

publication. It is a kind of character sketch of Ferdinand IV of

Naples (who would shortly become Ferdinand I of the Kingdom of Two

Sicilies) right after he had been restored to his throne after Napoleon's

defeat and the subsequent Restoration mandated by the Congress of

Vienna. The item appears to be a reprint from The Journal,

although I haven't yet managed to figure out which journal—probably

a British publication of the day. The writer pretty much confirms

other contemporary and subsequent descriptions of the king as being

affable and stupid. A lunkhead. That view is much kinder than some,

such as this sentence from a much later (1911) description of Ferdinand

in the Encyclopedia Brittanica: "...Ferdinand died on the

4th of January 1825. Few sovereigns have left behind so odious a

memory. His whole career is one long record of perjury, vengeance

and meanness, unredeemed by a single generous act..."

There

is other material on Ferdinand in the log entries in vol. 1 for

The Bourbons (1) and Eleonora

Fonseca Pimentel. Fersen (villa)—on Capri

Gambrinus (Caffè )

For such a city, Naples was tardy—the late 1700s—in coming to the idea that one could actually set up little coffee bars along the by–ways and maybe serve some sweets and pastries in the process. Such places were common in the rest of Italy in the late 1600s. Yet, the Neapolitans made up for lost time; by the mid–1800s there was scarcely a short stretch of street in Naples without a little coffee bar of some sort. That tradition continues to this day. Some are holes in the wall, and some are opulent. Indeed, calling the Caffè Gambrinus a coffee bar is like calling St. Peter's Cathedral a church; you're right, but the crime of paucity of description borders on a capital offence. The Caffè Gambrinus is on the ground floor of the large building that houses the Naples Prefecture at Piazza Plebiscito. One entrance is on that large square, itself; the main entrance is on Piazza Trieste e Trento (still known to many as Piazza San Ferdinando, named for the church on that square). Gambrinus is a few yards away from the Royal Palace, the San Carlo opera house, and the Galleria Umberto. It is at the beginning of two of the most famous streets in Naples: via Toledo (also known as via Roma) and via Chiaia, the main street that joined the downtown area of 1900 to the western part of the city. Gambrinus, thus, was the crossroads where music, art, and politics came together in the late 1800s to sit together and have a coffee and maybe a brandy or two. In other words, a watering-hole for intellectuals. Gambrinus was born as, simply, il Gran Caffè on its current premises in the 1860s. By the 1890s, with the great rebuilding of Naples, the risanamento, in full swing, it turned into the Caffè Gambrinus, using the name of the "patron saint of beer," that name deriving—according to one plausible etymology—from Jan Primus (John I), a 13th–century Burgundy prince. Thus, Gambrinus, like other establishments of its kind was and remains a place where you do more than just drink coffee. The premises consist of a main bar and pastry section plus six adjoining rooms, all of which are showcases of fin de siècle fashion, that 1890s wave of sophistication and world-weariness. The rooms are all vaulted and display in white bas relief various scenes from mythology. The walls are lined with thin, classical columns and reliefs of statuary, and there is ample use of large mirrors to increase light and the illusion of space. The mirrors alternate with equally large paintings of outdoor Neapolitan life of the day, not precise tromp l'oeil, but at least creating the pleasant sensation that you are looking out at the bay of Naples, a coast-line, fishermen, fashionably overdressed women strolling along the street, and even one of the ultimate in 1890s decadence—a woman smoking a cigarette! Neapolitan decadence of the 1890s is round and plump, not to be confused with the gaunt English decadence of the same period; all the women in these paintings, especially the smiling peasants, have 40 pounds on anything Aubrey Beardsley ever came up with. Gambrinus was closed in 1938 under the flimsy pretext that the noise was keeping the prefect and his wife—who lived in the same building upstairs—awake at night. In reality, all those artists, politicians, and writers had created their own little hotbed of discussion, the noise from which was keeping Fascist government officials awake on the eve of WW2. The establishment reopened in the 1950s.  This magnificent fountain is also known as the "Immacolatella".

Both names derive from two of the locations that have been home to

the fountain during its many travels. (Being moved is a risk you take

if you are a fountain in Naples. Click

here for another example.) The fountain was sculpted in the early

1600s and is the work of Michelangelo Naccherino (1559-1622) and Pietro

Bernini (1562-1629). It was first located near the Royal Palace near

a statue of "The Giant," recovered from the ruins of Cuma. In 1815

the fountain was moved to the port of Naples to be in front of the

Immacolatella, the old quarantine

station. It was then moved near the Carmine church at Piazza Mercato;

then to the gardens on the square of San Pasquale a Chiaia;

then finally, in 1905, when the new seaside road was finished during

the "risanamento" of Naples

the fountain was moved to its present location (see photo) at the

pituresque curve beween via Partenope and via Nazario Sauro not far

from the Castel dell'Ovo. This magnificent fountain is also known as the "Immacolatella".

Both names derive from two of the locations that have been home to

the fountain during its many travels. (Being moved is a risk you take

if you are a fountain in Naples. Click

here for another example.) The fountain was sculpted in the early

1600s and is the work of Michelangelo Naccherino (1559-1622) and Pietro

Bernini (1562-1629). It was first located near the Royal Palace near

a statue of "The Giant," recovered from the ruins of Cuma. In 1815

the fountain was moved to the port of Naples to be in front of the

Immacolatella, the old quarantine

station. It was then moved near the Carmine church at Piazza Mercato;

then to the gardens on the square of San Pasquale a Chiaia;

then finally, in 1905, when the new seaside road was finished during

the "risanamento" of Naples

the fountain was moved to its present location (see photo) at the

pituresque curve beween via Partenope and via Nazario Sauro not far

from the Castel dell'Ovo.

Amid the three rounded arches and above and on the sides of the fountain, besides the main basin adorned with marine life, the work is decorated with caryatids holding a cornucopia, as well as with the coats of arms of the city and of the Spanish vice-realm. The

Bernini involved with this fountain is, by the way, not the

Bernini of the great colonnade of St. Peter's in Rome. That would

be Giovanni Lorenzo Bernini (1598-1680). This Bernini--Pietro--was

his father. Gladstone's pamphlet on Naples

I came across a review of Gladstone's pamphlet in an 1851 issue of Littell’s Living Age, a New York journal that specialized in reprinting material from foreign journals. The reprint, in this case, is from The Spectator, a prominent journal of British liberalism. The

review is in the "Through the eyes of..." section of Around

Naples in English. Click here to

read that review. hand gestures (books) and Andrea de Jorio

One such volume, for example, is Comme te l'aggia dicere? (Neapolitan

dialect for "How can I explain this to you?"). The secondary title

is in Italian: Ovvero l'arte gestuale a Napoli (Or the Art

of the Gesture in Naples). It is by Bruno Paura and Marina Sorge

(1999. ed. Intra Moenia, Naples). It has 138 pages, with emotion

and message listed alphabetically—"scorn," "approval," "you

must be crazy!" etc.—all accompanied by photographs or drawings.

Comme te l'aggia dicere? has replaced older volumes, now

out of print, and will itself be replaced in a few years when someone

else comes out with a new one. Even foreign language guide-books

to Naples now generally contain a few pages of pictures and explanations

of gestures. (Even if your reading extends, alas, only to t-shirts,

you can get those, too: silk-screened front and back with Neapolitan

hand gestures plus explanatory captions.)

Installation Art '04

The

work bears an amazing resemblance to Serra's earlier "Torqued Ellipses,"

done in 1996, separate curved plates of towering steel, which, to

the untrained maximalist eye--with a bit of imagination--might be

fit together into a spiral. Leopardi, Giacomo (1798-1837)

There are few child prodigies in literature. Presumably, meaningful reflections on the human condition come from having a few years under your belt--time to love, struggle, wander and let those experiences set for a while, a process less necessary to early greatness in music and mathematics. Thus, we are amazed at Rimbaud and Mary Shelley writing fine literature at the age even of 19 or 20. Leopardi is in that unusual group. By the age of 16, he was a Latin and Greek scholar; and by 18 he had written lasting poetry. His natural precociousness was no doubt helped along by being a recluse for the first 20 years of his life, holing up in his father's vast library, teaching himself the classics as well as modern European languages. He suffered both from poor eye-sight (that got worse as he grew older) and by a deformity of the spine, a lifelong source of pain, physical as well as social.

If by melancholy we mean something like wistfulness, a longing for a happier past or even an unachievable ideal state, then much of Leopard's poetry is not even that. It is simply bleak. He writes of his own loneliness and of nature as a "betrayer" and "a brutal force." He writes of the "infinite vanity of everything." So if his friendship with the Ranieris made him as happy as he could ever be, maybe all we are saying is that he liked the Neapolitan sherbet and sweets, or that he got a kick out of trying to guess lottery numbers, or went to San Carlo (to fill in his total lack of musical culture), or "worshipped from afar" Paolina Ranieri. (She apparently--as a term of endearment, one hopes--referred to him as "il mio gobbetto"--my little hunchback.) Not much, but at least it is something.

Because of the quality--or even lack--of translations, Leopardi is not as well known in the English-speaking as he should be. Translators of poetry, of course, run the risk, as they say, of "losing poetry in the translation" and, at the other extreme, of "gaining poetry"--of writing a beautiful poem that is too original to really be called a translation. I know that Ezra Pound, Robert Lowell, and Robert Bly have translated some of Leopardi into English. My favorite English translation is of a poem written at the graveside of a woman. Her image has been cut into the tombstone. Leopardi says to the image: "Tal

fosti: or qui sotterra Ezra Pound's translation of these first few lines is: "Such

wast thou, That strikes me as perfect.  I live

near a street in Naples that will never change its name. This is remarkable,

since the roller–coaster of historical and social change plays

games with Neapolitan urban nomenclature like you wouldn't believe.

Via Roma used to be Via Toledo (or maybe it's the other way round);

Via Gramsci used to be Via Helena; even the street I live on—named

for Victor Emanuel II, the first king of united Italy—was originally

named for Queen Maria Theresa of Naples in 1850 when the street was

built. I live

near a street in Naples that will never change its name. This is remarkable,

since the roller–coaster of historical and social change plays

games with Neapolitan urban nomenclature like you wouldn't believe.

Via Roma used to be Via Toledo (or maybe it's the other way round);

Via Gramsci used to be Via Helena; even the street I live on—named

for Victor Emanuel II, the first king of united Italy—was originally

named for Queen Maria Theresa of Naples in 1850 when the street was

built.

The lucky, namechangeless thoroughfare I speak of is Via Maria Cristina di Savoia. She was born in 1812 and died in 1836, a tragically brief life. She was from the royal house of Savoy, the dynasty that eventually came to rule united Italy later in the century. Maria Christina was exceptionally devout and would have entered a convent but for family pressure to marry her off in one of those arranged cross–dynastic affairs that European royal houses used to think were so advantageous. In 1832 she was forced into a marriage with King Ferdinand II of Naples, obviously as a means to cement relationships between the northerners (Savoy) and southerners (Bourbon). Her husband was King "Bomba," (bomb), so–called for his suppression of revolutionaries in Sicily in 1848. He was the next–to–last king of Naples. Their son, Francis, would be the last king. She died two weeks after giving birth to him. Her husband's second wife was Maria Theresa, the original eponym of my street. In

her brief life in Naples, Maria Christina was totally devoted to

benevolent works, actively promoting expansion of crafts, small

industry, and institutions to provide for the poor. She was also

responsible for mitigating her husband's tendency to hand out death

sentences. She quickly became the focus of admiration—even

adulation—of the people. She was easily the most beloved queen

in the long history of the Kingdom of Naples. In short, she was

a saint. Not metaphorically, either. At her death, a cult sprang

up around her and her episodes of intercession (to use the Roman

Catholic terminology). The process to canonize Maria Christina began

in 1859 and she was beatified in 1872. I think she is the only queen

(or king) of Naples to be so honored. She rests in the Church of

Santa Chiara. Metastasio in Naples

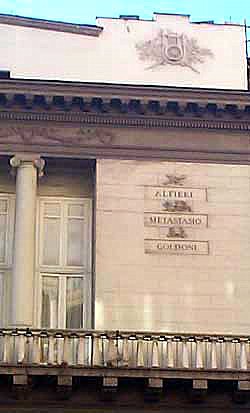

When the first operas started to play on Italian stages in the early 1600s, they were monuments to the admonition of Vincenzo Galilei (1520-1591--he is the father of the astronomer, Galileo) to other Florentine poets and musicians of the day not to let music get in the way of the story. "Singing should be just barely distinguishable from speaking," he said. However, such was the melodic and harmonic eloquence of such giants as Monteverdi and then the Neapolitan, Alessandro Scarlatti, that a century later the pendulum had swung completely to the other extreme. By 1700, Italian opera was about to expire from overwrought melody with banal and plotless doggerel hanging off the music almost as an afterthought. As a child, Metastasio was "discovered" by two literary patrons. The boy, from a modest family, was taken with wandering the streets of Rome and improvising poetry for passers-by, a feat so impressive that the patrons convinced Trapassi's father to give them custody of the child so that he might have an education worthy of his talent. Renamed "Metastasio" (a Greek form of his real name), the boy stayed in Rome for a few years, studying the classics--and producing at the age of 12 (!) a translation of the Iliad into Italian octave stanzas He continued his poetry improvisations so intensively that his health suffered. His guardians took him to Naples in 1718, where it was understood he would study law and put poetry aside, at least for a while. Metastasio's

name with those of Goldoni and Alfieri on the facade of San Carlo

Metastasio

took the time to study music in Naples, and was genuinely concerned

about the compatibility of music and text. He left Naples

in 1728 and eventually wound up in Vienna, but from his early works

in Naples, his destiny was sealed, and the legal profession lost,

no doubt, a learned professor of law or whatever else might have

been down that road for Metastasio. By the end of his life, not

only had his texts been set to music by some 400 different European

composers, but they were widely read for their literary value. Morse, Samuel

That is one more reason to dislike Samuel Morse. First, the code. I had to listen to Morse code for six hours a day for months while I was in the army. I wound up having very bad dreams in which giant succubus mosquitos danced on my ear drums taunting me with their incessant beeping and whining. Second, Morse was a Copperhead defender of slavery. Three, this thing about pizza. Sam.

Three words: dah-dit-dah-dah dah-dah-dah dit-dit-dah

I don't remember the exclamation mark.

The ads

caught my notice because I heard a dog speaking Neapolitan dialect

on TV! He is usually in the company of a beautiful young woman, where

he dispenses a world-weary running commentary (in Neapolitan, of course)

on the futile efforts of young men to make friends with said babe,

his mistress. These problems, he advises, can be resolved only by

buying the new Italian Telecom cell-phone that gives you two numbers,

call-waiting, color TV, broad-band access to the Interpol server,

and blood transfusions. So far, young Neo (as dog lovers call them)

is into his eighth or ninth ad. In one of them, he even has Sophia

Loren as a co-star. The dirty dog.  In

response to a query I have had as to whether there is such a

thing as "outlaw music" in southern Italy, the answer is 'yes,'

but it does seem strange that I should have to order a CD of

such music from a record company in Germany—but that seems

to be the case. In

response to a query I have had as to whether there is such a

thing as "outlaw music" in southern Italy, the answer is 'yes,'

but it does seem strange that I should have to order a CD of

such music from a record company in Germany—but that seems

to be the case.I checked around the city of Naples today for a CD called Il Canto di Malavita – La Musica della Mafia. It is listed in catalogues as being available from Pias Recordings in Hamburg. None of the Neapolitan stores I tried had it, though it might be available "under the table" somewhere in town. A website entitled www.malavita.com says, "The mere existence of these Mafia songs and the fact that they can be bought freely at markets throughout Calabria has led to heated and somewhat polemic debates in Italy. Critics have stated that they think it improper to sing the praises of those who live outside the rule of law and that to do so is to glorify their way of life." So, if I want to go prowl the flea-markets and music shops in Calabria, I might find it. "Bought freely" is an interesting oxymoron. First, a few comments about the Italian terminology. Malavita is the general Italian term for the criminal underworld, from unaffiliated street punks to "organized crime"—"the mob". Technically—though foreign usage does not respect this distinction (the title of that CD was supplied by the German company)—mafia refers only to Sicily; the Neapolitan branch of the same activity is called la camorra; south of Naples and down through the rough hills of Calabria to the end of the "boot" of Italy, the term is 'ndrangheta. The CD in question is, thus, music about Calabrian outlaws, the 'ndrangheta. The term "outlaw music," itself, invites confusion because it is not clear if one is talking about music by outlaws or music about outlaws. I am not sure if Robin Hood or, more recently, Jesse James, ever composed music about themselves, but I suspect they did not. Certainly, in English literature the most romantic manifestation of the outlaw ballad was by Alfred Noyes (1880-1959), who toed the narrow line of the law enough to attend Exeter College in Oxford and for a while serve as Professor of Modern English Literature at Princeton University. He wrote The Highwayman, a portion of which—long slid down between the sofa cushions in my head—now resurfaces as

The

wind was a torrent of darkness among the gusty trees, The

moon was a ghostly galleon tossed upon cloudy seas, The

road was a ribbon of moonlight, over the purple moor, And

the highwayman came riding, up to the old inn-door.

I

check and see that I have fused the last two lines into one;

there should be an extra "... And the highwayman came riding-riding-riding."

(Not bad, though, for ageing synapses!) I had, of course,

totally forgotten the most dramatic and Robin-Hoody part at

the end:

With

the white road smoking behind him and his rapier brandished

high! Blood-red

were his spurs i' the golden noon; wine-red was his velvet coat, When

they shot him down on the highway,

Down like a dog on the highway, And

he lay in his blood on the highway, with a bunch of lace at

his throat.

The

southern Italian music on the CD mentioned above is, however,

authentically Calabrian. The pieces range from historical ballads

about the origins of the 'ndrangheta to songs praising

omertà—the code of silence. There is no

doubt that they glorify life outside of the law. The CD sold

well in Germany and France. Part of the criticism by Italian

critics who have reviewed the CD is that foreigners are too

willing to accept the self-serving descriptions of the music

by the people who recorded it originally.

If these people ever were Robin Hoods, say the

Italian critics, those days are long gone. Today, they kill

judges, kidnap, sell drugs, run prostitution rings, shake down

the middle-class, and rake off great wads of money from public

works boondoggles. They do not steal from the rich and give

to the poor. They steal from everybody and keep it.

Cicco

Scarpello—known by his stage name, Fred Scotti—was

one of the performers of this outlaw music of Calabria. One

evening in April, 1971, he was shot to death in the street.

He had apparently been trying to seduce the woman of one of

those criminals he liked to sing about. With or without lace

at his throat, he was indeed shot down like a dog on the highway.

Find your own message.

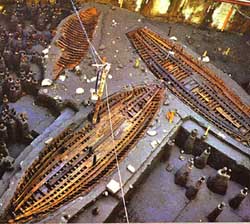

The palimpsest nature of urban Naples has been made even more evident by the recent discovery (January 2004) of the ancient port of Roman Naples. They have always known it was down there somewhere. It turned out to be just about where reconstructions of the city as it was during the first century a.d. had presumed it to be—right beneath what is now Piazza Municipio, adjacent to the Angevin Fortress, the Maschio Angioino, 100 yards or so in from the modern coastline and way down beneath the manmade landfill and rubble of 2000 years of history and the natural accumulation of 2000 years of mudslides and other geology. Construction for the Piazza Municipio station of the new underground train line had already unearthed more recent items, bits of structures that were plowed under in the 1890s to rebuild the square; then they found the old (meaning 400 years) outer walls of the nearby fortress. Now, beneath all that, archaeologists have brought to light a 30–foot Roman vessel and abundant pottery, sure signs that this was the Roman port. The expectation had been that they would find something sooner or later as the subway builders continued to dig and move east along the line of the old Roman (and Greek) wall. The next station down the line at Piazza Nicola Amore, still under construction, has now yielded the remains of an impressive imperial villa. Obviously,

there is much left to be uncovered. This leaves archaeologists

ecstatic; people who have to get to and from work, however,

have mixed feelings. They are already impatent with subway construction

that is months behind schedule. Workers doing the actual building

of the new train line are also uncertain about this turn of

events; whenever history and the needs of the modern city come

into conflict—as they do quite often in Naples—those

who dig and build generally have to stand aside and lean on

the their shovels until the archaeologists get finished mumbling

and cataloguing. In the case of a 30-foot wooden boat that has

to be delicately excavated, at least some workers may be sent

home—laid off—for a while.

Such directness occurs late and rather suddenly in Italian literature. Edoardo Scarfoglio was from Paganica in Abruzzo but lived and worked in Naples much of his life. He was among those Italian writers who started to write short fiction (the novella) in the late 1800s and then longer fiction, novels, a form ignored before then by Italian authors, largely bound, as they were (until Manzoni), to classical literary forms. Scarfoglio was successful early in life; he was in his 20s when he could be said to have "made it" as a writer of short, realist fiction, particularly with the publication of The Trial of Phryne in 1884. For whatever reason—perhaps because journalism was the natural vehicle for everyday language—he gave up "literature" and dedicated the rest of his life to journalism. He married the most prominent Italian woman writer of the day, Matilde Serao. Together they founded a number of newspapers, among which was Il Mattino, still the largest Neapolitan daily. Together, they moved Naples out of the backwaters and into the mainstream of Italian journalism; they provided space for some of Italy's fine talent of the day by serializing such writers as D'Annunzio. Scarfoglio's narrative skills are best seen in the novella, mentioned above: The Trial of Phryne. It is a retelling—set in small-town Italy of the late nineteenth century—of the trial of Phryne, a Greek courtesan from the fourth century, b.c. She was on trial for blasphemy. Her life was at stake and ultimately saved by her lawyer's appeal to the Greek concept that the Good, True, and Beautiful were inseparable and that such a Beautiful defendant must, therefore, be Good and True. She bared her breasts to the jury and was roundly and firmly acquitted. Sociologists use this episode to speak of such things as the rhetoric of silence in women's judicial supplication and rhetoric as a "craft of logos," where technique determines outcome, emerging as an indeterminate act outside Western definitions of rhetorical process. The rest of us think of it in terms of, "Listen, sweetheart—smile, look beautiful, and keep your mouth shut." Scarfoglio's Phryne is a young village beauty by the name of Mariantonia, guilty of poisoning her mother–in-law. Italians who have not read Scarfoglio know the episode anyway from the film version, one part of Alessandro Blasetti's 1952 episodic film, Altri Tempi (Other Times), starring Vittorio De Sica as the lawyer and Gina Lollobrigida as Phryne/Mariantonia. In his appeal to the court, De Sica says, "Does not the law of our land state that the mentally handicapped be acquitted? Why then should such a physically endowed creature as this magnificent woman beside me not be acquitted, too?" As

a writer and literary critic Scarfoglio advocated the liberation

of Italian literature from French influence. As an editorialist,

he supported such things as Italian expansionism in Africa and

the Aegean in the 1890s. Indeed, one finds this reference to

him in a lengthy article on "The Italians in Africa" in a copy

of The Fortnightly Review from October, 1896:

That was written by an Englishman during the heydey of British imperialism. Clearly, what was sauce for the English goose was not meant for the swarthy Italian gander. Scarfoglio

had insatiable wanderlust, at one point lamenting his life as

a "hack journalist" and claiming that had been born to "hunt

elephants on the banks of the Omo and sail amidst the fissures

of the polar ice-pack." Aboard his vessel, Claretta,

he sailed at least to the eastern shores of Greece and coastal

Turkey. From his ship, he wrote Letters to Lydia, passionate

prose disclosing his affair with the actress Lydia Gautier.

He separated from his wife, Matilde Serao, in 1902 and died

in 1917.

Scarpetta did not come from a theatrical family but was on the stage by the age of four. He worked almost exclusively at the San Carlino theater in Naples, where he created a character that became his stage alter-ego (say, in the same way that the Tramp was synonymous with Charlie Chaplin): Felice Sciosciammocca, a typical, good-natured Neapolitan, just trying to get by. The name "Sciosciammocca" translates from Neapolitan to "breath in mouth"—thus, with "Felice" (Happy) you get something like open-mouthed, wide-eyed and perhaps a bit scatter-brained. The character was a break with the traditional portrayal of the Neapolitan streetwise Everyman and, as an implied stereotype, draws immediate comparison to the well-known, historical Neapolitan "mask" of Pulcinella. Scarpetta's character, however, has none of the barbed wisdom of Pulcinella—nor was it meant to. One story says that Scarpetta, as a child, was terrified by an on-stage appearance of Pulcinella. Scarpetta's grandson, Mario, has commented that the figure of Sciosciammocca, at the time, seemed to be more of what Naples was about (or trying to be about) than did the darker character of Pulcinella. Naples was no longer the capital of an old-line absolutist kingdom. It had recently been taken up into united Italy; it had strivings away from treachery and intrigue, and towards the cosmopolitan and urbane. There was nothing of Pulcinella's cryptic mocking behind Sciosciammocca's "mask" --no psychology. He wore no mask. He was the light, modern, nineteenth-century Neapolitan male, with not even a trace of the tragic Chaplinesque clown—in a way, almost a throwforward to, say, something like Jack Lemmon's character in Some Like it Hot. Scarpetta

dedicated much of his early activity to translating into Neapolitan

the standard Parisian farce comedy of the day, such as Hennequin,

Meylhac, Labiche and Feydeau. His own original comedies comprise

some 50 works, the best-known of which is probably Miseria

e Nobiltà (Misery and Nobility) from the year 1888.

The work is well known, too, as a 1954 film featuring the great

Totò as Felice Sciosciammocca; the film also features

the young Sophia Loren. The plot, roughly, involves poverty-stricken

Felice and his friend, don Pasquale, masquerading as aristocratic

relatives of a young woman in order to get her parents approval

for a marriage to a young prince. The ploy works, of course,

and Felice and don Pasquale are rewarded. They splurge on a

feast, and the last scene in the film has Felice, don Pasquale,

and the rest of the famished family scrambling onto the kitchen

table to shove food into their mouths (photo, above). It is

this type of nonsensical slapstick that irked Scarpetta's intellectual

critics at the turn of the century. They wanted social commentary.

Scarpetta just wanted to make people laugh. He wrote his last

work in 1909 and passed away in 1925.  Along with his great predecessor,

Luca Giordano, Solimena is the

best-known painter of the Neapolitan Baroque.The easiest

painting by Solimena to find in Naples is in the Church of Gesù

Nuovo (located in the square of the

same name), but you might actually miss it if you go into

the church for the reason that you should go into a church.

That is to say, you have to go in and turn your back on the

faithful and look directly above the entrance to see the massive

and spectacular The Expulsion of Heliodorus from the Temple.

Even a graphic dunce such as myself (anti-references available

upon request!) notices Solimena's signature charateristics--light

and color, from the white charger in the middle to the splashes

of the bright blue robes. I don't know why artsy types of the

day didn't like it; perhaps it was too "busy" (it is indeed

jammed) or perhaps not sombre enough. Indeed, descriptions of

Solimena's works abound in vocabulary such as "golden light,"

"lovely harmonies of colour," "brilliant luminosity," "vibrant,

atmospheric light," etc. Along with his great predecessor,

Luca Giordano, Solimena is the

best-known painter of the Neapolitan Baroque.The easiest

painting by Solimena to find in Naples is in the Church of Gesù

Nuovo (located in the square of the

same name), but you might actually miss it if you go into

the church for the reason that you should go into a church.

That is to say, you have to go in and turn your back on the

faithful and look directly above the entrance to see the massive

and spectacular The Expulsion of Heliodorus from the Temple.

Even a graphic dunce such as myself (anti-references available

upon request!) notices Solimena's signature charateristics--light

and color, from the white charger in the middle to the splashes

of the bright blue robes. I don't know why artsy types of the

day didn't like it; perhaps it was too "busy" (it is indeed

jammed) or perhaps not sombre enough. Indeed, descriptions of

Solimena's works abound in vocabulary such as "golden light,"

"lovely harmonies of colour," "brilliant luminosity," "vibrant,

atmospheric light," etc. Other of his works in Naples include The Massacre of the Giustiniani at Chios, in the Capodimonte museum; The Trinity, the Madonna and St Dominic, in the sacristy of San Domenico Maggiore; and various frescoes in the churches of San Paolo Maggiore and San Domenico Maggiore. His self-portrait (shown above) is in the Museum of San Martino. He is responsible, as well, for the frescoes on the ceiling of the royal bedroom in the Royal Palace, put there to celebrate the marriage of Charles III (the first Bourbon king of the then newly independent Kingdom) Maria Amalia of Saxony in 1737. Solimena had a long and very successful career and was, at the height of his powers, one of the most sought-after painters in the Europe of his day.

Also noticeable in Naples are the many old churches that are closed. Some of them were holes in the wall even when they were built; they certainly could not have served very large congregations. But not all of the closed churches are small ones; there are some very large houses of worship in Naples that are closed—for example, the gigantic church of the Gerolamini in the historic center of the city not far from the cathedral of Naples. Less impressive in size, but still noteworthy is the church of San Giorgio dei Genovesi (photo) on via Medina between the City Hall and the main police station. There is no longer even a sign on the front to indicate the name of the church, although there is a recent sign indicating that the premises are now the site of something called the University Chapel. In any event, I have never seen the building open. The church was built in 1587, which makes it old in the some places in the world but not in Naples; it stands next to a church that was, in fact, built 300 years earlier. For whatever its value has been to the faithful over the centuries, San Giorgio dei Genovesi is at least as interesting in the secular history of the city, since it was built on the site of the very first commercial theater in Naples. When the Spanish moved into Naples in 1500, making the city and all of southern Italy part of the great Spanish Empire, they brought with them their cultural institutions—for example, the large church-run orphanages that trained children in music (the first "conservatories"). Another example—the case, here—theaters: venues where the first troupes of professional actors could present themselves in the art of the comedy. The theater is referred to in documents of the period (the mid-1500s) as, simply, la commedia. (The later church on the same site was then popularly called San Giorgo alla commedia vecchia [old theater]. The theater was the professional home to acting troupes from Spain "playing the provinces," and it provided a stage for the improvised antics of the masked and costumed figures in the then innovative Italian Commedia dell'arte. Such characters included the famous Neapolitan stereotype character, Pulcinella. The

property where the la commedia stood was purchased by members

of the Genoese community in Naples for a new church. Then, in

the first decade of the 1600s, "show business" continued in

a new theater built to replace la

commedia. This was the Teatro dei Fiorentini,

an establishment that continued through the centuries of demolition

and rebuilding in the immediate area and even today still exists

in its more recent incarnation as a cinema and, now, of all

things, a Bingo hall. The other major theater from the same

period in Naples was the theater of San Bartolomeo, built in

1620 and redone in the 1640s in order to accommodate the first

performances of the "new music" from the north—early opera.

San Bartolomeo would then function until it was replaced by

the grand theater of San Carlo in 1737.

The first 20 years of Verdi's very long career as a composer were between 1840-60, a period that corresponded to a period of great social turmoil in the Kingdom of Naples. It is, thus, not surprising that Verdi--one of the great voices for Italian unity--would not get along very well with the absolutist Bourbon kings of Naples. At least a few of Verdi's early operas were presented at San Carlo almost as soon as they were composed: Oberto, conte di S. Bonifacio; and a comic opera entitled Il finto Stanislao. Then, Alzira, a piece set in Peru, actually premiered in Naples in 1845. All of these were uncontroversial as to political content and sailed by the censors in Naples with no problem. All of those works have remained obscure to this day. (Alzira did give Verdi, however, the chance to work with the greatest Neapolitan librettist of the day, Salvatore Cammarano, author of the libretti for a number of Donizetti's operas.Verdi and Cammarano collaborated on three other works: The Battle of Legnano, Luisa Miller, and Il Trovatore.) Luisa Miller premiered in Naples in 1849. To fulfill his contract with San Carlo, Verdi had been planning an opera called Maria de' Ricci, based on a medieval siege of Florence, very much in keeping with his timely preoccupation with freedom and revolution. The censors didn't want any part of any siege of any Florence, so Verdi and Cammarano came up with Luisa Miller, based on Schiller’s play, Kabale und Liebe. It is strange to me that the censors let Nabucco pass at all, even after almost a decade. It was composed in 1840 and played in San Carlo in 1848, the year of great revolutions throughout Europe. The theme of liberty--indeed, even the unofficial national anthym of early Italian unity, Va pensiero sull'ali dorate-- got by the censors. Maybe the far away and long ago setting seemed as innocuous to them as Peru had seemed in Alzira.

Even after Gustavo III had been watered down to Un Ballo in Maschera and the European king had been turned into a 17th-century govenor of Boston (!), the censors still didn't like it; it had to premiere in Rome in 1859. Shortly thereafter, what Neapolitan censors thought or didn't think became moot--along with the rest of the Bourbon Kingom of Naples. Verdi did manage a bit of on-the-spot revenge after the fall of the kingdom. His Battle of Legnano opened the 1861 season in the new Naples of the new Italy. The

traditional, non-Swedish Un Ballo in Maschera played

in 1862, but 2004 will be the first time that the original has

played in Naples. I have a feeling that any number of opera-goers

are going to walk by San Carlo, look up at the posters and say:

"Hmmmm, Gustavo III. Verdi. Gee, I never heard of that

one." * Who knows. Maybe this is a good sign. Riccardo, the

tenor, Count of Warwick and Governor of Boston can take a break

after all these years.

-------------------------

*San

Carlo is taking no chances. The posters tell you in fine print

that Gustavo III is the original version of Un

ballo in maschera, and that the opera was originally meant

to be premiered in Naples.

Viviani was born in Castellemare of a poor family. He appeared at the age of 4 on the stage in Naples, lost his father at 12, and took over the care of his mother and the rest of the family. By the age of 20, he had a solid stage reputation throughout Italy. As a young actor, he also played in Budapest, Paris, Tripoli, and throughout South America. His plays are in the "anti-Pirandello" style; that is, they are less concerned with the pyschology of people than with the lives they lead, in this case the human stories of the common people of Naples. Perhaps his best known work is "L'ultimo scugnizzo" (The Last scugnizzo) (1931), scugnizzo being the underclass Neapolitan street kid, who lives by his wits on the fringes of legality. In this case, the "last scugnizzo" tries to adjust to a more normal adult life, almost makes it, but reverts to his earlier self as a result of a personal tragedy. Viviani was a good musician, as well, and composed songs and incidental music for many of his earlier works. One such well-known melodrama is "via Toldeo di notte," a work from 1918 in which Viviani reprises some of his earlier melodies and even employs American cake-walk and ragtime rhythms to tell the story of the "street people" of via Toledo, the most famous thoroughfare in Naples. It is presented in the form of a succession of songs with little or no linking dialogue and with only a few instruments as accompaniment. Thus, it was a somewhat anomalous form for Italian musical theater of the day. English terminology has used "music drama" to describe such items. Viviani, himself, described it as a "Commedia in un atto (versi, prosa e musica)." The disastrous

Italian defeat at Caporetto in 1917 in WWI led to a reappraisal in

Italy of national values and a subsequent crackdown on such frivolities

as musical theater and vaudeville. This austerity led Viviani to concentrate

more and more on straight drama, a trend that he continued until the

end of life. During the Fascist era, he also had to contend with the

regime's hostility towards theatrical works presented in regional

dialects rather than the national standard language. Viviani persisted

and has been vindicated; all in all, however, he is not as well known

outside of Italy as he deserves to be. Jane House Productions will

present a US premiere of his Via Toledo di Notte at the CUNY

Graduate Center in New York in late 2004. A edition of the complete

theatrical works of Viviani was published by Guida in 1987.

Women's Journals in Naples in the 19th Century

Vittoria Colonna was a literary and artistic journal for women published in Naples in 1846 and 1847 "under the auspices of the Queen Mother". Twenty-one issues appeared. The journal was inspired by and named for the great Renaissance poet, Michelangelo's sketch of whom appears at the top of this entry.

|

Well,

it didn't happen. In late November, all of Naples was glued to the

tube for the announcement--THE announcement--live, direct from Switzerland.

The Swiss were about to make their decision as to the site of their

2007 defense of the America's Cup, a major regatta (also--for you

landlubbers-- known as a boat race).

Well,

it didn't happen. In late November, all of Naples was glued to the

tube for the announcement--THE announcement--live, direct from Switzerland.

The Swiss were about to make their decision as to the site of their

2007 defense of the America's Cup, a major regatta (also--for you

landlubbers-- known as a boat race).  I have a rather eclectic collection

of books about Naples: archaeolgy, history, music— whatever

strikes my fancy, really. It's not a huge collection, but it is

stuffed with many of those tiny and ephemeral pamphlets that come

out all the time about the "Caves of Naples," "The Customs

of Naples," "The This & That of Naples." Maybe a few hard ones,

such as The Major-Minor Shift in the Neapolitan Song as

a Manifestation of the Existentialist Dichotomy in the Popular Psyche,

(OK, I made that one up.) I have a few standard works such as Acton's

The Last Bourbons of Naples, and I am an absolute sucker

for passages about Naples in 19th century works such as

I have a rather eclectic collection

of books about Naples: archaeolgy, history, music— whatever

strikes my fancy, really. It's not a huge collection, but it is

stuffed with many of those tiny and ephemeral pamphlets that come

out all the time about the "Caves of Naples," "The Customs

of Naples," "The This & That of Naples." Maybe a few hard ones,

such as The Major-Minor Shift in the Neapolitan Song as

a Manifestation of the Existentialist Dichotomy in the Popular Psyche,

(OK, I made that one up.) I have a few standard works such as Acton's

The Last Bourbons of Naples, and I am an absolute sucker

for passages about Naples in 19th century works such as  And

here is John Horne Burn's classic, The Gallery, about the

seamy kaleidescope of Neapolitan life at the end of WWII played

out in the famous

And

here is John Horne Burn's classic, The Gallery, about the

seamy kaleidescope of Neapolitan life at the end of WWII played

out in the famous  Together

with

Together

with  I

have no profound sociological insight to offer on the persistence

of organized crime, the camorra (the Neapolitan Mafia) in

Naples, but I offer this from The Galaxy, an Illustrated Magazine

of Entertaining Reading, a journal published in New York from

1866 to 1878 by Sheldon and Company. Among contributors to the very

first issue were heavyweights such as William Dean Howells, Henry

James, Bayard Taylor and Anthony Trollope.

I

have no profound sociological insight to offer on the persistence

of organized crime, the camorra (the Neapolitan Mafia) in

Naples, but I offer this from The Galaxy, an Illustrated Magazine

of Entertaining Reading, a journal published in New York from

1866 to 1878 by Sheldon and Company. Among contributors to the very

first issue were heavyweights such as William Dean Howells, Henry

James, Bayard Taylor and Anthony Trollope.  As

a writer, Cervantes struggled unsuccessfully through much of the

rest of his life. He applied for various jobs, even in Spanish possessions

in the Americas but was turned down for one reason or another. The

bulk of his work was published in the last ten years of his life.

Indeed, he started to write Don Quixote while in debtors'

prison in 1600. The first part was published in 1605.

As

a writer, Cervantes struggled unsuccessfully through much of the

rest of his life. He applied for various jobs, even in Spanish possessions

in the Americas but was turned down for one reason or another. The

bulk of his work was published in the last ten years of his life.

Indeed, he started to write Don Quixote while in debtors'

prison in 1600. The first part was published in 1605.

Approaching

Capri from the port of Naples, the Villa Fersen is a white speck

clinging implausibly, magically to the side of the cliff hundreds

of feet above the sea at the far eastern end of the island. It is

set—certainly because Fersen was looking for seclusion—at

one of the remotest spots on the island. The villa was finished

in July of 1905 and officially named "Villa Lysis" for a disciple

of Socrates mentioned in one of Plato's dialogues. Fersen had many

of the extravagant furnishings brought from Paris, had the phrase

Amori et dolorum sacrum ("Sacred to love and pain") inscribed

over the entrance, and in general cleared the decks for full-scale

debauchery quite in keeping with the climate of the times on Capri

(see the log entry on

Approaching

Capri from the port of Naples, the Villa Fersen is a white speck

clinging implausibly, magically to the side of the cliff hundreds

of feet above the sea at the far eastern end of the island. It is

set—certainly because Fersen was looking for seclusion—at

one of the remotest spots on the island. The villa was finished

in July of 1905 and officially named "Villa Lysis" for a disciple

of Socrates mentioned in one of Plato's dialogues. Fersen had many

of the extravagant furnishings brought from Paris, had the phrase

Amori et dolorum sacrum ("Sacred to love and pain") inscribed

over the entrance, and in general cleared the decks for full-scale

debauchery quite in keeping with the climate of the times on Capri

(see the log entry on  Naples

is a city that prides itself on coffee—nay, believes itself

to be the sole arbiter of what sets a magnificent brew apart from

the swill they serve in the rest of the world. Naples even has its

own, special Neapolitan coffee percolator, a three-piece contraption

that requires three-ring dexterity to turn upside down (or maybe it's

rightside up) at just the right moment during the brewing process.

Naples

is a city that prides itself on coffee—nay, believes itself

to be the sole arbiter of what sets a magnificent brew apart from

the swill they serve in the rest of the world. Naples even has its

own, special Neapolitan coffee percolator, a three-piece contraption

that requires three-ring dexterity to turn upside down (or maybe it's

rightside up) at just the right moment during the brewing process. The

entry on

The

entry on

This year's ritual installation of art in Piazza Plebiscito

features a work entitled "Naples," by the master of massive minimalism,

San Francisco artist Richard Serra (1939-). It is a large spiral

(already called "Contraception of the Gods" by those who view with

some disdain the city's unabashed dedication to this kind of display).

Entering into the giant orange scuplture of curved and bending steel

plates, you spiral in, leaning in and out with the curves of the

walls, to the center, where you can look up and see the clock tower

on the facade of the royal palace (see photo and insert). The individual's

perception as he navigates the deceptive geometry of this small,

tilted space set in the larger space of the square, itself, is what

gives validity to the work, says the artist. Clearly, to be a private

experience--to be at all touched by the suggested metaphor of yourself

in a similarly skewed private life-space set in the space of the

world at large--the wandering in and out is best done slowly and

alone and not as part of a curious herd elbowing their way in and

out--unless, of course, you spend much of your time elbowing your

way through life wondering what it's all about. That, too, is possible.

This year's ritual installation of art in Piazza Plebiscito

features a work entitled "Naples," by the master of massive minimalism,

San Francisco artist Richard Serra (1939-). It is a large spiral

(already called "Contraception of the Gods" by those who view with

some disdain the city's unabashed dedication to this kind of display).

Entering into the giant orange scuplture of curved and bending steel

plates, you spiral in, leaning in and out with the curves of the

walls, to the center, where you can look up and see the clock tower

on the facade of the royal palace (see photo and insert). The individual's

perception as he navigates the deceptive geometry of this small,

tilted space set in the larger space of the square, itself, is what

gives validity to the work, says the artist. Clearly, to be a private

experience--to be at all touched by the suggested metaphor of yourself

in a similarly skewed private life-space set in the space of the

world at large--the wandering in and out is best done slowly and

alone and not as part of a curious herd elbowing their way in and

out--unless, of course, you spend much of your time elbowing your

way through life wondering what it's all about. That, too, is possible.

As the narrow-gauge Circumvesuviana railway wends

its way east along the coast from the city of Naples in the direction

of the Sorrentine peninsula, it passes through a number of small

stations on the slopes of Vesuvius. Two of the stations have

to do with the life of this, Italy's greatest Romantic poet. One

station is named, simply, "Leopardi" and the other "Ginestre"

(the Italian name for the broom plant, the yellow-flowered shrub

that grows abundantly on the slopes, and, as well, the title of

a remarkable poem by Leopardi). If this so-called "poet of melancholy"

ever found any relief at all in his terribly unhappy life, perhaps

it was here, in and near Naples.

As the narrow-gauge Circumvesuviana railway wends

its way east along the coast from the city of Naples in the direction

of the Sorrentine peninsula, it passes through a number of small

stations on the slopes of Vesuvius. Two of the stations have

to do with the life of this, Italy's greatest Romantic poet. One

station is named, simply, "Leopardi" and the other "Ginestre"

(the Italian name for the broom plant, the yellow-flowered shrub

that grows abundantly on the slopes, and, as well, the title of

a remarkable poem by Leopardi). If this so-called "poet of melancholy"

ever found any relief at all in his terribly unhappy life, perhaps

it was here, in and near Naples.  He

spent time in his home town of Recanati in central Italy as well

as in Rome and Florence. Then, in 1833, he moved to Naples to keep

the company of Antonio and Paolina Ranieri, brother and sister,

whom he had met in Rome. He then moved a number of times in Naples.

The cholera epidemic of 1835 caused him to move farther out of the

city, winding up at Villa Ferrigni, now called the Villa delle

Ginestre (photo); it is near the small knoll upon which perches

the monastery of Sant' Alfonso. Vesuvius looms directly above, and

Leopardi's final home is, indeed, near both of the modern train

stations mentioned above, named in his honor. It is here that he

wrote that 1,800 years had passed "...since the peopled places disappeared,

crushed by fiery might, and the peasant busy at his vine...still

lifts his eyes suspiciously to the fatal peak..." (in the prose

translation of George Kay from the Penguin Book of Italian Verse,

published in 1958).

He

spent time in his home town of Recanati in central Italy as well

as in Rome and Florence. Then, in 1833, he moved to Naples to keep

the company of Antonio and Paolina Ranieri, brother and sister,

whom he had met in Rome. He then moved a number of times in Naples.

The cholera epidemic of 1835 caused him to move farther out of the

city, winding up at Villa Ferrigni, now called the Villa delle

Ginestre (photo); it is near the small knoll upon which perches

the monastery of Sant' Alfonso. Vesuvius looms directly above, and

Leopardi's final home is, indeed, near both of the modern train