© 2004 Jeff Matthews & napoli.comAround

Naples in English

|

| The finding has been of particular interest, as orangutans have long been thought to be loners, leaving little possibility for creating culture. Yet researchers found that at one site all orangutans gave a Bronx cheer before going to sleep… |

The

part about the “Bronx cheer” drew my attention. I, for one,

say “hear! hear!” to our orangutan cousins, the “oran

utan” of the Asian jungles, in their strivings towards our own

more advanced cultural habits. To that end, I offer this information.

The

part about the “Bronx cheer” drew my attention. I, for one,

say “hear! hear!” to our orangutan cousins, the “oran

utan” of the Asian jungles, in their strivings towards our own

more advanced cultural habits. To that end, I offer this information.

Neapolitans, like everyone else, commonly lament that things are not as good as they used to be. For one thing, water. In the old days, drinking water in Naples was a cold and pure experience, as refreshing as falling into a snowbank in Heaven. Second, bread. Convoys of panisti (breadsteaders?) still make weekend forages to the outlying areas, looking for El Doughrado, the village fabled to bake bread the old-fashioned way—in a brick oven fired by wood. Third, the topic of this brief attempt at interspecies cultural aid and the final bit of damning evidence that things ain't what they used to be: they say that there is no one left who can sound a 'pernacchio' good and true.

The pernacchio . This unvoiced trill or buzz made by protruding the tongue between the lips and forcibly expelling air—possibly using the palm or back of the hand as an aid to increase back–pressure and, hence, amplification, is a common acoustic token (hereafter referred to as a 'sound') of disapproval, contempt, derision, disapprobation, odium, dislike, dissent, disdain, scorn or contumely. In some parts of the United States it is called 'a Bronx cheer'. The general English term, however, is 'raspberry' and it is one of the few examples of so-called Cockney Rhyming Slang to find its way into common use throughout the English speaking world. The complete phrase is 'raspberry tart,' a rhyme with the common English term, now considered vulgar, for the sound produced by flatulence and which the 'raspberry' is said to be in imitation of. It has also given us the slang verb 'to razz,' meaning 'to make fun of'.

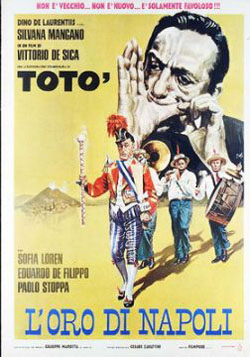

The proper Italian term is 'pernacchi-a,' from the Latin vernacula (servant or slave), thus, a sound that presumably only a lowly person would make. The pernacchia is said to have enjoyed its Golden Age in the early 20th century in Naples. Indeed, in Neapolitan, the prevalent term is 'pernacchi-o,' the -o suffix indicating masculine grammatical gender. It is a common misconception, perpetuated by misguided lexicographers that the masculine form is simply a dialect variation and the two forms are interchangeable. The following passage [my translation] from a delightful book of tales entitled L'Oro di Napoli (The Gold of Naples) by Giuseppe Marotta will show that this is not the case:

| The 'pernacchio' is not the 'pernacchia'. The former can be strong or weak, long or short, massive or frail, aquiline or snub; but it is always masculine, always constructive and diligent, always on the job. The latter is soft and indolent; puffy, white and reclining like a harem concubine on a carpet. Suffice it to say that don Pasquale resorted to the feminine version of the gesture only for trivial matters; for example, in answer to a summons to pay his rent or bills, or when a client would point out to him that the handle on one of the riding crops which don Pasquale handcrafted had not been turned quite properly, and don Pasquale simply hadn't the energy to answer with a curt, "There's nothing more I can do with it. |

In another passage, the author describes the varieties of pernacchio that only the dedicated Neapolitan raspberry virtuoso is capable of producing:

| Their infinite range, their register and modulations. Don Pasquale Esposito had them all! The violent quake of the 'breast pernacchio,' renting the air and hurling itself out over land and sea; but he also had the subtle nuances of the 'head pernacchio,' which one could describe the way one does the song of a nightingale...There was a three-note theme... and then go on for two more pages; furthermore, he had both an affirmative and negative pernacchio, a tragic and a comic one; with only his lips he could send forth an inward and lyrical, remote, dense sound, freeing his pent-up emotions like a torrent; he could declare with his pernacchio, and he could allude; he could sum up, and he could go into minute detail; he had nouns and adjectives; his was the pernacchio of genius. |

(The film version of L'Oro di Napoli presents the above paragraph in a scene that is now part and parcel of Neapolitan popular culture. The great actor/playwright, Eduardo De Filippo, demonstrates the "infinite range, register and modulations" of the true pernacchio for his neighborhood friends. It is said that you know nothing about the pernacchio until you have seen that film! "...In the film poster, above, Eduardo demonstrates the classic hand position for the best rendering of the pernacchio)

The pernacchio

is an archetypal expression of contempt at being beaten up by the world,

and in Naples a person's measure of worth is the ability to hurl it

even in the face of the Ultimate Indignity. Again, L'Oro di Napoli:

| It is worth commenting upon the final moments of Don Pasquale. Thinking that it would be difficult to feel the pulse or heartbeat through all the fat, the doctor held a small mirror up to the mouth of the dying man. Don Pasquale's breath fogged the glass with strange and vague marks, small puffed circles crossed by lines and mysterious markings. They weren't accidental signs; they were symbols, a message, parts of a puzzle. The faithful in attendance—those who believed in signs and could decipher them—knew what they were witnessing: Don Pasquale, always a person of few words, and now burdened by impending death, was availing himself of his last breath to blow one last formidable, supreme pernacchio at this life, which was now abandoning him. |

In spite of the perception that the real pernacchio is dead or dying, the word is out that a champion has come forth, a pretender to the long vacant throne of don Pasquale Esposito in the examples cited above. He is known simply as the Pernacchione --the Great Phantom Raspberry Blower. Residents of the area of Naples called Port' Alba speak of him in whispered awe, the way peasants used to talk of King Arthur or Robin Hood—or the way we used to recite The Highwayman around a campfire: "And still of a winter's night, they say, when the wind is in the trees/ And the moon is a ghostly galleon tossed upon stormy seas…"

He is said

to appear whenever the downtrodden and oppressed are in need of venting

their displeasure. Maybe you've been in the world's longest queue at

the post-office for two hours, ulcerating and grumbling at the overpaid

slow-motion dolts up there behind the counter who are the source of

all your torment, when suddenly it is upon you—Pzzzzzzztttttt!

a great rip-roaring engine of vengeance, a sibilant and clarion wail

of outrage sounding and resounding off the high vaulted marble arches

of bureaucratic arrogance! A Pzzzzzzztttttt! as heroic and homeric

as the laughter that bursts the bonds of Tyranny—and you turn

and he has gone, without even waiting for a thank-you, without even

leaving a silver bullet. But he'll be back. Once more there is hope.

He's everywhere. He's everywhere.

Bagnoli; risanamento (4); urbanology (2)

"(Whatever Bagnoli may become, today it is still blighted by the relics of its industrial past.)"

The

president of Italy was in Naples yesterday to attend the opening of

a new section of La Città della Scienza (The City of Science),

a large area—about 4 square miles—in Bagnoli, devoted to

the development of a combination hands-on science museum and exposition

grounds.

The

president of Italy was in Naples yesterday to attend the opening of

a new section of La Città della Scienza (The City of Science),

a large area—about 4 square miles—in Bagnoli, devoted to

the development of a combination hands-on science museum and exposition

grounds.

The Gulf of Naples really has two bays. In the east, the Bay of Naples, itself, includes—at the extreme end—Sorrento; then, the towns along the slopes of Vesuvius, the city of Naples, proper, and the areas known as Mergellina and Posillipo. Rounding Cape Posillipo, you come to the other bay: the Bay of Pozzuoli. It is very historic and includes the small isle of Nisida, the town of Bagnoli, the fabled Flegrean Fields , Pozzuoli (with Lake Averno, the entrance to Hell in The Divine Comedy) and Baia, the site of the Roman imperial port. The bay—and the Gulf of Naples—ends at Cape Miseno, directly across from the islands of Nisida and Ischia.

At the beginning of the 1900s, the eastern end of the Bay Pozzuoli—precisely, the town of Bagnoli and the area running out to Nisida—went through years of extended industrial development. A steel mill was built there as part of the mammoth development of the whole Neapolitan area, a project lasting decades and known as the Risanamento of Naples. The alternative plan—the one that was not chosen—involved a quite different approach, architect Lamont Young’s plan that would have turned Bagnoli into a pseudo-Victorian imitation of a British seaside resort.

As

a result of the extreme industrialization of Bagnoli, the area simply

turned into an overbuilt blight of grime, noise, traffic and all those

things that one would rather not associate with what is, by common observation,

one of the most scenic bays in the Mediterranean. Things changed in

the 1990s: they closed the steel mill and started a gradual conversion

to a post-industrial local economy more based on tourism. The City of

Science has been open since November 2001 and is the cornerstone, so

to speak, of the whole plan. It fronts the sea with a beach and small

port for recreational craft. Eventually, the rejuvenation of the area

should "ripple" along the seaside past Bagnoli and Pozzuoli to Baia

at the other end. It is an ambitious plan, and one hopes for the best.

As

a result of the extreme industrialization of Bagnoli, the area simply

turned into an overbuilt blight of grime, noise, traffic and all those

things that one would rather not associate with what is, by common observation,

one of the most scenic bays in the Mediterranean. Things changed in

the 1990s: they closed the steel mill and started a gradual conversion

to a post-industrial local economy more based on tourism. The City of

Science has been open since November 2001 and is the cornerstone, so

to speak, of the whole plan. It fronts the sea with a beach and small

port for recreational craft. Eventually, the rejuvenation of the area

should "ripple" along the seaside past Bagnoli and Pozzuoli to Baia

at the other end. It is an ambitious plan, and one hopes for the best.

Architecture (1), Spanish in Naples

| But if there is an eighth wonder in the world, it must be the dwelling houses of Naples…You go up nine flights of stairs before you get to the “first floor. —Mark Twain, The Innocents Abroad |

Indeed, as one strolls almost anywhere in Naples—through the old historic center of town or out along the road known as the Riviera di Chiaia—the large buildings are still obvious, even in an age when skyscraper technology seems to drawf all that has gone before. In most cases, the old apartment houses in the center of town—say, on via dei Tribunali or via San Biagio dei Librai—have a looming, monolithic look to them. They were originally single–family dwellings. By “single,” of course, I mean a single, noble, large family with dozens of servants and a need for lots of room for extravagant parties and somewhere to keep the horses and coaches. I’m sure the gigantic Palazzo of the Emperor of Constantinople did the trick in the 1300s. It takes up an entire block in the heart of the old center; it is an Angevin structure from the 1300s. Today—at ground level—there is a long row of small shops and stalls, and the upper floors house dozens of families.

The later Spanish buildings are functionally very similar: an entrance large enough for coaches to pass through, an internal courtyard, and around the courtyard a four or five–story array of balconies, corridors and rooms. In many cases in the downtown area, the courtyards now contain shops; the upper floors have long since been subdivided into separate family units. The trick is to keep the old façades and walls—then pop in a spanking new modular kitchen or bathroom. (I have a friend who lives in a perfectly modern apartment in Palazzo Casacalenda at Piazza San Domenico Maggiore. What looks like a closet door in his living room actually opens onto an internal stone spiral staircase from the 1600s leading to the roof of the building.)

When the Spanish broke out of the confines of the original city walls and moved west out to what is now the Riviera di Chiaia, they put up an impressive string of villas along what was then the seafront. (The more recent park, built by the Bourbons and now known as la Villa Comunale (The Public Gardens) now lies between the original villas and the water.) Most of those villa now have similar histories of being turned to uses other than housing dukes and princes.

Palazzo Carafa di Roccella is an interesting example. It sits two blocks back from the Riviera di Chiaia on one of the main shopping streets in that part of town. It is an enormous red building, a block long and four or five stories high, and it has been abandoned and had scaffolding on the façade for as long as I can remember—sort of a permanent suggestion that they might be getting ready to do something with it some day. It has been through various incarnations since it was built in the 1600s, including a period in the early 20th century of total abandonment and one in the 1960s when it almost fell prey to the land developers’ wrecking ball (in which case, that part of town would now have even more of those unsightly cement cracker boxes they built to house the “economic miracle” of 40 years ago in Naples.) Now, however—apparently, while I wasn’t looking—the construction cranes have almost finished their job, the paint is almost dry, “some day” is here, and the plan is for this old, old building to house a new museum of modern art.

[ See

here for a separate entry on the "Spanish Quarter" of Naples.]

Art, modern (2)

An exorcism,

of sorts, will take place at Piazza Plebiscito today when local poet

Salvatore di Natale will parade around near the bronze skulls installed

in the pavement (see here) and mutter

incantations to rid the city of the Evil Eye caused by the presence

of said crania. The poet’s name translates as Savior of Christmas,

which seems potent enough to me, but for this occasion he has redubbed

himself Mussasà Abdel Natal.

I, myself, have seen (photo, left)

the three old Fiat 500s parked, painted and installed as art in the

new subway station on via S. Rosa, so I sympathize with this letter-to-the-editor

in il Mattino. The gentleman says that he had finally evolved

a satisfactory intellectual interpretation of the artistic display of

old shoes in one of the new stations when he noticed the other morning

that someone had added a beat-up old hat and jacket to the exhibit.

Is this, he asks, an addition by the artist, perhaps something we might

call “Process Art”? Or is it crass and sarcastic vandalism?

Or—one more possibility—is it perhaps a simple act of charity

by some artistically illiterate, but good-hearted, person who has mistaken

the exhibit for a collection point for the needy?

I, myself, have seen (photo, left)

the three old Fiat 500s parked, painted and installed as art in the

new subway station on via S. Rosa, so I sympathize with this letter-to-the-editor

in il Mattino. The gentleman says that he had finally evolved

a satisfactory intellectual interpretation of the artistic display of

old shoes in one of the new stations when he noticed the other morning

that someone had added a beat-up old hat and jacket to the exhibit.

Is this, he asks, an addition by the artist, perhaps something we might

call “Process Art”? Or is it crass and sarcastic vandalism?

Or—one more possibility—is it perhaps a simple act of charity

by some artistically illiterate, but good-hearted, person who has mistaken

the exhibit for a collection point for the needy?

Scugnizzo (1)

The

Neapolitan word scugnizzo is normally rendered in English as

“street urchin,” although that term—and others such

as “ragamuffin”—is too archaically cute to be much

help in understanding how these children of the street have typically

lived—and still live—in Naples. They are always poor, go

to school when they have to, and hustle through the rest of their young

lives by hook or crook; that is, with small jobs such as running errands,

washing windshields at stoplights, and, inevitably in some cases, by

descent into the seamy underworld of petty-crime. They scrape by. Indeed,

scugnizzo apparently comes from medieval vernacular Latin, “cugnare,”

meaning “to scrape”.

The

Neapolitan word scugnizzo is normally rendered in English as

“street urchin,” although that term—and others such

as “ragamuffin”—is too archaically cute to be much

help in understanding how these children of the street have typically

lived—and still live—in Naples. They are always poor, go

to school when they have to, and hustle through the rest of their young

lives by hook or crook; that is, with small jobs such as running errands,

washing windshields at stoplights, and, inevitably in some cases, by

descent into the seamy underworld of petty-crime. They scrape by. Indeed,

scugnizzo apparently comes from medieval vernacular Latin, “cugnare,”

meaning “to scrape”.

Neapolitan lore and literature is full of scugnizzi (the plural). Any collection of late 19th–century photography of Naples has the obligatory shot or two of the bare–foot kid hitching a free ride on the back of the horse–drawn trolley or thumbing his nose at the well–to–do. There is also a well–known 1931 play, “The Last Scugnizzo” by Raffaele Viviani (photo shows Nino D'Angelo starring in a recent version of that play) and the 1946 Oscar–winning bit of Italian neo–Realism entitled “Sciuscià” directed by Vittorio De Sica. That title, itself, was a neologism in Neapolitan dialect from the local pronunciation of “shoe shine,” as in the post-war phrase, “Hey, Joe, you want sciuscià?” Also, the Neapolitan maker of films of social involvement, Nanny Loy, turned out his Scugnizzi in 1989; that film is the basis for the musical of the same name by Mattone and Vaime currently playing to enthusiastic audiences in Naples. It has a mostly amateur cast of young street–wise Neapolitans who know what they are singing and dancing about. The piece is set against the backdrop of the jail for juvenile offenders—still in operation—on the small isle of Nisida off the shores of Bagnoli in the Gulf of Naples.

The irony is that while the president of Italy, Carlo Azelio Ciampi, was in Naples the other day enjoying a production of the musical, a 13–year–old boy, characterized in at least some newspaper accounts as a scugnizzo was shot to death while trying to steal a motor-scooter. He and his 17–year–old accomplice pulled up on their own scooter alongside a young man driving alone on his. “Give us your bike!” one of them shouted. The potential victim, it turns out, was an off–duty policeman in street garb, and he was armed. By his account, the two both wore hoods. He turned to make a run for it, and they followed him. This time, the one on the back of the scooter pointed a pistol at him and the driver yelled, “Shoot! Shoot!” At that point, the young cop pulled out his own pistol and—again, by his account—fired one “downward warning shot” in their direction. Whatever the case, the bullet struck the 13–year–old driver in the face and passed through to wound the accomplice on the rear seat. The young driver died shortly thereafter, and his accomplice was taken to a hospital. He will recover. The pistol he had pointed at the cop was found at the scene. It was a plastic toy.

The mother

of the child is screaming (through lawyers) that her son was murdered

by a trigger-happy cop. The policeman—only 20–years–old,

himself—claims he was afraid for his life and fired only to warn

his assailants. Investigations are now going on into whether he may

be charged with, as the law puts it, “culpable use of excessive

force in self-defence”. I have no idea how that will turn out,

nor do I know anything about the boy that died. I do think, however,

that musicals about poverty lend an air of illusory delight to a condition

that will not be sung and danced away.

Presepe (2), Christmas (6), San Gregorio Armeno (3)

The holiday season was officially over a couple of days ago with the coming of la befana. The shops on the main thoroughfare for buying one's holiday decorations, via San Gregorio Armeno, are closing down, although some of them stay open most of the year to handle general tourist trade.

One such shop displays the most unlikely cast of characters ever intended for a "presepe" (nativity scene) in Naples. It is a display of figures dubbed, collectively, "The Shepherds of the Clean Hands" --"clean hands" (photo) being the name of the great anti-crime campaign started in Italy in the early 1990s. Depending on mood of the shopkeeper, figures can be identified as anyone from the mayor of Naples to the Prime Minister of Italy to the various magistrates involved in the struggle—or just generally famous and infamous characters. This year, Osama Bin Laden was twice present—once sitting on an elephant! He is directly next to a more traditional rendering—that of a beheading—originally meant to be the execution of John the Baptist. The sign, however, tells us that this is the head of "Bossi," an extremely unpopular (in southern Italy) politician from the north. Busts at the very front of the display this year included Mussolini, the playwright Eduardo de Filippo, and the great Neapolitan comic, Totò.

There is

no particular ideological ax being ground in any of this. It is in keeping

with the whole hodge-podge nature of the entire street, where, in the

midst of items such as the Star of Bethlehem and The Three Wise Men,

which might focus your devotion to the spirit of the season (once you

get them home), there are also boxes of white plastic skulls (from the

Fontanella tradition— see

here for a relevant entry), horrible recordings of “Here Comes

Santa Claus” and paper mache mannequins of Laurel and Hardy.

Architecture (2)

| The

worst place to put a building like this. |

Like most people who know nothing of what they spout off about, I know what I like, and of all the chunks of so-called architecture I don't like in Naples, the Jolly Hotel downtown (photo, above) is at the top of my list. This grotesque people-box looks as if some brain-dead band of miscreants first built a tawdry one–story hick motel and then decided to pancake fifteen of them straight up. They even put a neon sign on top. “Jolly,” it says. Only Italians know that the “Jolly” is the Joker in a deck of cards. Visitors from elsewhere no doubt think that this the place to come to get your jollies. If I had real power, I would contact the aliens who wasted so much valuable time mutilating cattle in the Rockies and kidnapping FBI agents for The X-Files and get them to abduct the architects of this monstrosity and hurt them real good, and then zap that baby straight into the center of the sun.

While they're

at it, the aliens can take the bottom station of the Chiaia cable–car

at Piazza Amedeo. That used to be a quaint turn–of–the–century

cable–car station, a sweet little number that cradled you while

you waited and let you forget about traffic jams and such. Then, they

tore it down and put up a concrete and steel–girder station. At

least they tried to put one up, because when the people in the adjacent

apartment house saw the Quonset Hut from Hell inching up next door,

they sued the city to stop construction. They won their case, but in

its infinite delay the law didn't stop the building until the steel

beams were inches from the windows in the apartment building. For well

over year, tenants couldn’t leave their windows open without feeling

that this skeleton with a corrugated tin hat was leering in at them.

(The law was finally translated into action. The steel girders are gone

and residents can now glance out and have an unobstructed view of what

is left of the station.) If the station had been finished as designed,

it was surely destined to wind up like its sibling, the cable–car

station of the Montesanto line in the Vomero section of town. This thing

looks like what you get when you sneak up on the Führerbunker

and spray it with shaving cream. The aliens can have that one, too.

On the other hand, I like the castle at the port of Naples (photo, left). It's good

solid fourteenth–century monolithic fortress architecture. It

has what every twelve–year–old boy could ask for in a building:

crenels, merlons, battlements, arrow loopholes, bastions, casemates,

turrets, and a moat. A moat, for Pete's sake! One that used to have

crocodiles in it! (I realize that story is not true, but I enjoy repeating

it.) Sadly, cars now park where crocodiles used to prowl, but that is

not the fault of the fortress. I also like the Galleria Umberto across from the San

Carlo opera house. It's an 1890 hybrid of a shopping mall and a

cathedral, a glass and girder dome sheltering four vast naves below.

Its construction was a boon to that part of town and it is still a kind

of sitting–room for the city; you wander in, have a coffee, check

out the shops, and if you go on Saturday or Sunday mornings, maybe even

wind up as an extra in a film, since the Galleria is the place where

local directors rightfully figure they can find at least a few suitably

strange characters such as yourselves.

On the other hand, I like the castle at the port of Naples (photo, left). It's good

solid fourteenth–century monolithic fortress architecture. It

has what every twelve–year–old boy could ask for in a building:

crenels, merlons, battlements, arrow loopholes, bastions, casemates,

turrets, and a moat. A moat, for Pete's sake! One that used to have

crocodiles in it! (I realize that story is not true, but I enjoy repeating

it.) Sadly, cars now park where crocodiles used to prowl, but that is

not the fault of the fortress. I also like the Galleria Umberto across from the San

Carlo opera house. It's an 1890 hybrid of a shopping mall and a

cathedral, a glass and girder dome sheltering four vast naves below.

Its construction was a boon to that part of town and it is still a kind

of sitting–room for the city; you wander in, have a coffee, check

out the shops, and if you go on Saturday or Sunday mornings, maybe even

wind up as an extra in a film, since the Galleria is the place where

local directors rightfully figure they can find at least a few suitably

strange characters such as yourselves.

Now that

I am being opinionated and Philistine about architecture, here is some

more—and I know the hard time I am going to get on this. I like

the architecture of Fascism in Naples. Now, it is no secret that from

the Great Pyramid of Cheops to Louis XIV's Palace at Versailles, big

governments build big. Nor does it take any profound symbol–crunching

to understand architecture as extension of the tyrant's ego. Yet, in

our own century, this kind of fervor has produced such ugliness that

the results would be funny if they didn't remind us of the grim realities

that accompanied them. I'm thinking primarily of the architectural corn

that Hitler planted in Germany in the 1930s, replete with over–sized

statues of Siegfried. Almost as bad were the grim mastodons of Socialist

Realism in the Soviet Union—a succession of joyless, clumsy and

intimidating buildings put there, no doubt, to remind you to shut up.

The Italian examples of

totalitarian architecture—at least the ones I have seen in Naples—don't

strike me that way at all. Yes, they are big, but they are big and shining

and optimistic. The great white passenger terminal at the port of Naples

(photo, left) , finished in 1939, looks, itself, like some magnificent

vessel about to set sail. The main post–office at Piazza Matteotti

is the best example, however. It could be a set from the science–fiction

film of the 1930s, Things to Come. (The post-office was, in fact,

completed in 1936, also known—as the friendly inscription on the

side reminds us—as "Year XIV of the Fascist Era". That inscription

was recently restored such that it is completely and un–selfconsciously

legible.) The great smooth black and white marble façade is lined

with row after row of rectangular windows, so symmetrical and unmoving

that the building itself looks entranced. At first glance, it might

all be one giant tribute to the static perfection of the right-angle—in

short, a big box. Yet, that is deceptive, for the smooth façade

curves into the entrance, producing two pseudo–columns almost

as tall as the building, itself, and the entire considerable length

of the building is actually a gigantic curve. Thus, instead of flatness,

we have some three–dimensional geometry of straight lines and

curves. Surely, this is what a space station should look like.

The post–office

is, indeed, art–deco, that "futuristic" style from the 1930s,

the clean, simple forms of which kept cropping up at exhibitions and

World's Fairs of that decade, telling us what the world would look like

fifty years down the road. One 1930–ish prediction missing from

the main post–office, I suppose, is a transparent people–moving

tube, high above ground, leading away from the building, perhaps in

the direction of the spaceport or the planetary weather control station.

And in place of the personal electric helicopters zipping about in front,

there is a real live 2003–ish traffic jam. But just as with the

fortress down at the harbor, that's not the fault of the building.

Frederick II

A

statue of Frederick II is the second in a row of eight along the façade

of the Royal Palace in Naples; they show the dynasties which ruled The

Kingdom of Sicily (later known as the Kingdom of Two Sicilies or, simply,

the Kingdom of Naples) from the Normans

in the 11th century to the unification of Italy eight-hundred years

later. They are all the same size, but if they were hewn to scale in

terms of historical importance, none would be larger than Frederick.

It would be very hard to fit this last great medieval emperor, this

scholar, diplomat and warrior into that tiny niche.

A

statue of Frederick II is the second in a row of eight along the façade

of the Royal Palace in Naples; they show the dynasties which ruled The

Kingdom of Sicily (later known as the Kingdom of Two Sicilies or, simply,

the Kingdom of Naples) from the Normans

in the 11th century to the unification of Italy eight-hundred years

later. They are all the same size, but if they were hewn to scale in

terms of historical importance, none would be larger than Frederick.

It would be very hard to fit this last great medieval emperor, this

scholar, diplomat and warrior into that tiny niche.

Knighthood and chivalry; popes and princes; kings, castles and Crusades; valor and skullduggery—all these things tumble together in our hazy modern perception of what the Middle Ages were all about. The Middle Ages are, indeed, confusing, but Frederick II provides an excellent focal point if we wish to understand not only the Middle Ages, but the essential point that some of the great issues which caused conflict then—religion, power, monolithic states versus cultural diversity—have not yet been resolved.

Centuries of struggle between the Church and the State in Europe came to a head in the 1200s. On the one hand, politically, Europe had been reformed by Charlemagne a few centuries after the fall of the Roman Empire with the view that The Empire, a vast monolithic state, should continue. In spite of Charlemagne's failure to forge a lasting empire, that idea took hold. It was, in hindsight, a rather futile endeavor in light of the emergence of separate 'national' identities in Europe—the French, the Germans, the Spanish and the Italians; yet, the idea remained that they could be joined through the single overarching person of the emperor. A strong contender among European royal houses of that age to provide just such a strong emperor was the German house of Hohenstaufen, the house of Frederick II.

On the other hand was the Church of Rome. It had come into its own, on the worldly plane, in 756, when Charlemagne's father, Pepin III, rendered unto Christ a lot of what had belonged to Caesar: land. That gift—a large part of central Italy—was the beginning of the Papal States, a church-state ruled by the Pope King. Over the next few centuries, a papal vision took form, a vision of Europe as a single theocracy with earthly princes subject to the princes of the Church, or, in the words of Pope Gregory VII, pope from 1073 to 1085: "The Holy See has absolute power over all spiritual things: why should it not also rule temporal affairs? God reigns in the heavens; His vicar should reign over all the earth." Clearly these two points of view on how Europe should be ruled were destined not to get along very well. And, indeed, they did not.

Frederick II of Hohenstaufen was born near Ancona in the Papal States in 1194. He was the grandchild of emperor Frederick I and beneficiary of the marriage of his own royal family into that of the Norman rulers of the Kingdom of Sicily (a kingdom, remember, that included the southern Italian mainland). Frederick was crowned King of Sicily as a young child, and he spent much of his childhood in the south. His mother appointed Pope Innocent III guardian of the child, a fact that may have fooled the Pope into thinking that here, some day, at last would be an emperor the Church might get along with.

Frederick was crowned Holy Roman emperor at age 26 and set about continuing the Church/State struggle that his grandfather had waged years earlier. His task was to unite the north of Europe, the lands of the German princes, with the south, the Kingdom of Sicily. Standing in the way was the Church, the Papal States, aided by some central and northern Italian city-states that had become independent of imperial authority and liked it that way. These, in essence, were the battle lines: the so-called "Ghibellines" (from the German place name "Waiblingen"), in favor of a strong emperor vs. the "Guelphs" (from "Welf," the name of a Saxon royal family, who supported Papal authority.

Frederick had his own son installed as King of the lands of Germany, setting the stage for eventual unification of north and south. He then set about solidifying his own rule in the Kingdom of Sicily. He built a chain of castles and border fortifications, built a naval as well as a merchant fleet, and created a civil service for which candidates were trained at the very first European state university, which he founded in Naples in 1224.

Bound by oath to undertake a Crusade, Frederick finally did so, and, amazingly, through a series of complex negotiations—as opposed to the usual bloodshed—obtained Jerusalem, Bethlehem and Nazareth from the sultan al-Kamil of Egypt. Considering the bloody Crusades of the previous century and the enmity between Christianity and Islam of that period, the fact the Frederick II of Hohenstaufen wound up—peacefully!—being crowned king of Jerusalem in the Holy Sepulcher in 1229 must rank high in the annals of diplomacy. Remembering his background, perhaps it is not surprising. Frederick had been raised in Sicily within living memory of Norman rule, that last great period of tolerance in European history, a time that saw Greeks, Italians and Arabs all forge their respective cultures—including religions—into a single state that worked. Frederick, himself, was fluent in Greek, French, Latin, vernacular Latin (which became Italian) and Arabic. (In his spare time, Frederick also wrote a treatise on falconry, considered one of the first European examples of natural history, based, as it was, on Frederick's own observations of the creatures in the wild.)

The emperor's behavior in Jerusalem gave the Pope something to ponder, for Frederick had issued a proclamation comparing himself to Christ, recalling his earlier remarks, supposedly in jest, that Moses, Christ and Mohammed had been impostors! (There is actually an extant document entitled Three Great Imposters; there are, to be sure, other possibilities as to the author of that document, but Frederick is a plausible choice.) Papal troops invaded Sicily shortly thereafter; after all, it surely could not have been very comforting to a Pope to realize that there was now a powerful emperor with a Messianic complex on the loose. Frederick nevertheless managed to return to Italy, defend his kingdom, and smooth things over with the Papacy.

In 1231 Frederick came up with a new constitution for the Kingdom of Sicily. It was the first time since the rule of the Byzantine emperor Justinian in the 6th century that the administrative laws of a European state had been codified. The constitution was revolutionary, anticipating the central authority and enlightened absolutism of a later age.

Frederick's troubles in the north were growing, however. He was unable to thwart the resistance by northern Italian city-states and the princes of Germany to imperial rule. Also, Pope Gregory IX, fearful of eventual encirclement by an earthly empire, excommunicated Frederick in 1239. Frederick countered by invading the Papal States in 1240, threatening to take Rome, itself. He did not carry out his threat, however; he settled for taking 100 clerics prisoner, thereby reinforcing his reputation not only as an oppressor of the Church, but perhaps as the Anti-Christ, himself.

In 1245 the Pope declared the Emperor to be deposed. The effectiveness of such a declaration clearly depends on (1) ability to enforce, and (2) willingness to comply, neither of which elements were in great abundance. At the time of his death in 1250 Frederick was still in a strong position, but within 25 years, his heirs had fallen victim to the same struggle with the Papacy that had taken up his own life. The last Hohenstaufen pretender, Conradin, was executed in Naples by the Angevin rulers who had replaced Frederick.

Frederick

was entombed in the cathedral of Palermo (photo, left), surrounded by

symbols of Roman Catholic, Greek Orthodox and Arab respect, eulogies

to an emperor as well as appropriate tributes to the peculiarly southern

fusion of cultures that had shaped him. Almost immediately the belief

took hold that he would return some day to restore the Empire. Even

Frederick II was not that much larger than life, but the Messianic overtones

of such an idea help us understand just what it meant to command true

awe in the Middle Ages.

Frederick

was entombed in the cathedral of Palermo (photo, left), surrounded by

symbols of Roman Catholic, Greek Orthodox and Arab respect, eulogies

to an emperor as well as appropriate tributes to the peculiarly southern

fusion of cultures that had shaped him. Almost immediately the belief

took hold that he would return some day to restore the Empire. Even

Frederick II was not that much larger than life, but the Messianic overtones

of such an idea help us understand just what it meant to command true

awe in the Middle Ages.

So, who won the battle? Not Frederick, clearly. But not the Church, either. By encouraging anti-Imperial sentiment, the Church unwittingly helped foster the new European consciousness of "nationality". Within half a century of Frederick's death, France was so strong that the French king had the Pope taken hostage, and eventually forced the removal of the Papacy from Rome to Avignon. When the Papacy returned to Rome almost a century later, Italy and the times would be fertile soil for the new ideas of the Renaissance, an unprecedented wave of creativity that the Church itself would promote—and which had been foreshadowed by Frederick's wide-ranging abilities.

Anthropolgy, Neapolitan culture (1),

I’m

reading a fascinating book entitled The View from Nebo. How Archaeology

is rewriting the Bible and reshaping the Middle East, by Amy Dockser

Marcus (Little, Brown and Company. 2000. Boston.) Strangely enough,

I am reminded of Naples. The section that draws my attention is a chapter

on the relationship of modern Jordan to the ancient Ammonites, a people

contemporary of the Israelites at the time of the destruction of Jerusalem

by the Babylonians in the sixth century b.c. The salient point for the

author is that modern Jordanians, for various reasons, fail to realize

how connected they are historically to a people—the Ammonites—who

were true “survivors,” true builders of what archaeologist

Oystein LaBianca has termed “indigenous survivor structures”.

I’m

reading a fascinating book entitled The View from Nebo. How Archaeology

is rewriting the Bible and reshaping the Middle East, by Amy Dockser

Marcus (Little, Brown and Company. 2000. Boston.) Strangely enough,

I am reminded of Naples. The section that draws my attention is a chapter

on the relationship of modern Jordan to the ancient Ammonites, a people

contemporary of the Israelites at the time of the destruction of Jerusalem

by the Babylonians in the sixth century b.c. The salient point for the

author is that modern Jordanians, for various reasons, fail to realize

how connected they are historically to a people—the Ammonites—who

were true “survivors,” true builders of what archaeologist

Oystein LaBianca has termed “indigenous survivor structures”.

Far from

disappearing from history, the Ammonites used such “survivor structures”

as developing a strong sense of family and tribalism, decentralizing

the administration of food and water supplies, keeping a very low profile

in the face of overwhelming force (so low, in fact, that they apparently

had a network of “cave villages” beneath the very ground

that Nebuchadnezzar’s armies were occupying. Interestingly, also,

is that one of the “strategies” was the development of a

“culture of hospitality that created a network of sharing favors

and information…” The key phrase in the chapter is:

| …the Ammonites had survived for so long because they had been open to outside cultural influences and trade with their neighbors, always finding a way to adapt these things to their own circumstances. |

Much of that applies to Naples; it is quite clearly a “survivor culture”. I think that is a positive term. “Resilient” and “adaptive” would be others. “Sponge culture”—which I have heard—has negative overtones I don’t like, implying a parasite culture, one that takes but never gives. I have heard “chameleon culture,” as well. I don’t like that one, either, perhaps because of the implication of deceit and lack of originality. None of that is true of Naples. What is true is that Naples is the oldest continuously inhabited center of large population in Europe. You can trace the steps these people have taken from the Greeks to the Romans; then through the independent duchies to the Normans, French, Spanish and on into modern-day Italy. At each step of the way, they have reinvented themselves through strategies very similar to those mentioned above: adapting outside influences to their own circumstances; bending but not breaking in the face of power; reliance on friends and family; and hospitality.

This makes me wonder if there is less of a clash—or, at least, if there are more flexible boundaries—between “insider and “outsider” in Naples. We all know that there are things that “mark” us as outsiders in another culture. Language is certainly one of them. Again in the Bible, the Gileadites distinguished their own soldiers from the Ephraimites on the basis of the pronunciation of the word “shibboleth”. Those who could not pronounce the “sh” correctly were the enemy and paid the price. If you don’t speak the language—one huge shibboleth—you will not fit in. It comes as a surprise to many, however, that even when they do speak the language, and even if they “say” all the other general cultural shibboleths properly, they still don’t fit in. They can never “unmark” themselves. Naples is not one of those cultures. Perhaps it has cultural markers that are less rigid—or, at least, more forgiving. It’s almost as if Neapolitans change their own pronunciation of “shibboleth” to fit yours. Thus, any perception that I may have of not “fitting in” may be just that—my own perception, the result of the quirk-ridden cultural and personal baggage that I carry around with me. (Admittedly, I am embarrassed to walk into my morning coffee-bar and ask, “Say, fellows, do I fit in?”)

It certainly

seems less incongruous to me now than once upon a time to walk out of

a 17th-century Spanish monastery and a concert of Neapolitan Baroque

music and directly into the MacDonald’s across the street where

American jazz or home–grown Neapolitan rap music is coming through

the in–house speakers. There are two possibilities: none of it

fits, or it all fits. Maybe I do, too—more than I think.

Language/s (2), "baloney"

(Sorry.

You'll have to read the entry to find out what this photo is all about.)

(Sorry.

You'll have to read the entry to find out what this photo is all about.)

From the Department of Fanciful but Pretty Good Etymology. I see that even the OED (Oxford English Dictionary) is hazy about the word “baloney,” in the sense of “humbug” or ”rubbish”:

Commonly regarded as from Bologna (sausage) but the connection remains conjectural.

I had a Neapolitan—or, at least, southern Italian—explanation all worked out, and it wasn’t bad. It wasn’t true, but it wasn’t bad. It is well-known (according to a local TV station, and why would they lie?) that immigrants to the US from these parts would commonly smuggle forbidden sausage past customs inspectors by hollowing out large blocks of cheese and stashing the meat in there. Thus, assuming that “baloney” is a cute diminutive from “Bologna” (probably) and if a certain kind of Bologna sausage is a smuggled item, then “baloney” becomes a synonym for “that which is false”. Unfortunately, that well-constructed syllogism is almost certainly low-grade bockwurst, if not downright baloney, since southern Italian immigrants were smuggling a totally different kind of meat, and I don’t think you could take in cheese, either.

A better explanation is that in the city of Bologna, there used to be a medieval market that traded in phoney gold, such that there is a common doggerel proverb in Italian that says:

“L’oro

di Bologna/si fa nero per la vergogna”

“Gold from Bologna turns black from shame.”

There is even a common Italian verb, sbolognare—which contains the name of the city—meaning “to get rid of something,” with the implication that the object is, if not worthless, at least not useful. That expression is probably connected with the trade in fool’s gold. Though there is no Italian expression that uses the name “Bologna,” itself, as a synonym for “worthless,” that meaning might have developed as an Italian-Americanism within the immigrant community.

The sausage in question is mortadella, a concoction of pork, donkey and wild boar—a mystery meat minced by medieval monks. The mortadella from Bologna was so highly prized that even today in Italy the name of the city is a synonym for the meat. You walk in and buy Bologna. Thus—let’s see how this is doing, so far—Bologna, fool’s gold, mortadella, immigrants—ergo, mortadella (baloney) is a metaphor for that which is not authentic. Also—if you have seen the 1971 film with Sophia Loren, La Mortadella—she tries to walk past the customs station in New York with one very large piece of Bologna, only to be told that “you can’t bring salami into the country”. (In the photo, above, Sophia is the one in the lower right.)

“It’s not salami. It’s mortadella,” she says.

The rest of the film revolves around the almost theologically fine distinction between minced pig, donkey, and boar, and minced whatever-else goes into “real” sausage. Thus, there is that aspect, as well: mortadella/Bologna/baloney as second-rate meat.

I hope

I get a nice letter from the OED. And I challenge them to say “mystery

meat minced by medieval monks” really fast. Five times.

Buffalo Bill

For no

reason that I can determine, il Mattino, the largest Neapolitan

daily ran a photo the other day with a simple caption and no story.

The photo showed a well-tended grave site. The caption read:

| The legend of Buffalo Bill is still alive. After more than a century the myth holds on. Every year, millions of persons visit Colorado and the tomb of Colonel William Cody and his wife. |

End of

story. The paper missed the chance to tell its readers about Buffalo

Bill’s visit to Naples in 1890.

European fascination for the American

West was never more in evidence than in the late 1800s. Cody—after

a lifetime of hunting, scouting and soldiering— took his enormously

successful Wild West show on two tours of Europe. In 1887 he and his

troupe went to Britain where they played to enthusiastic crowds—indeed,

to an enthusiastic Queen Victoria, herself, who liked the show so much

that she went back to see it a second time. Everyone was eager to see

the fabled buffalo hunter and Indian fighter, the sharp–shooting

Annie Oakley and bands of real Sioux warriors and, maybe—as did

the Prince of Wales—even ride on the fabled Deadwood Stage!

Two years later, they returned to Europe and went to Italy where they were invited to the Vatican to attend the celebration of the tenth anniversary of the coronation of Pope Leo XIII. Also, in Verona, Cody fulfilled his ambition of exhibiting his "Wild West" (he disliked the term "show") in an ancient Roman amphitheater. (In Rome he was unable to fulfil his dream of playing in the Coliseum, itself, as there was too much rubble and stone cluttering the arena; he settled for having himself and his troupe photographed in front of it.)

A high

point of the visit to Rome was a bronco-busting challenge "grudge match"

between Buffalo Bill's cowboys and true working cowhands from the Maremma

region in central Italy, men who spent much of their time working with

the Cajetan breed of horse, the wildest and most unmanageable in Italy.

The Prince of Teano challenged Cody's men to break the Cajetans. Twenty

thousand spectators saw the contest. The Rome correspondent of the New

York Herald wrote:

| The brutes made springs into the air, darted hither and thither in all directions, and bent themselves into all sorts of shapes, but all in vain. In five minutes the cowboys had caught the wild horses with the lasso, saddled, subdued and bestrode them. Then the cowboys rode them around the arena while the dense crowds applauded with delight. |

Depending on who is telling the story, the Maremma cowboys were then only marginally to moderately successful at trying to duplicate that feat on Cody's horses.

Buffalo

Bill opened in Naples on January 26, 1890. (An imaginative local had

counterfeited more than two-thousand tickets—and why am I not

surprised at that?!—producing great confusion at the opening.)

An ad in the Neapolitan newspaper, il Paese, that day announced:

| Buffalo

Bill's Wild West! 100 Indians! 100 Marksmen! Hunters & Cowboys! 200 animals, including wild buffalos! 2 Week Engagement—Daily, 2,30 p.m. Corso Meridionale, at the Rione Vasta. Tickets: 1, 2, 3, 5 lire. |

And so Buffalo Bill let the West run wild in Naples for a while. Bear in mind that no one—not Cody, not his company, and certainly not the people who watched them perform throughout Europe—viewed this as a circus. It was more of a replay, if you will, of current events. In 1890 the Indian Wars that had raged along the American frontier had not even totally subsided. The West may have been 'won,' but the combatants were still very much alive. The Native Americans in Cody's troupe were not stage 'Indians'—they were the real thing, many of the very same Sioux braves who had fought Custer at the battle of the Little Big Horn. Indeed, they were in Cody's troupe only because he got them released into his custody for his tour after they were imprisoned in the wake of the last great Sioux uprising. Back in America, Chief Sitting Bull was still alive and still their leader, (although he would be "shot while trying to escape" from internment later that same year of 1890). (Cody would live until 1917.)

The Neapolitan

papers praised Cody and his band:

| That which may seem to the everyday Neapolitan to be a kind of game, an idle display of skill, is nothing less than a common necessity of everyday life in a country where acrobatic agility, boundless audacity and prowess are conditions for survival. |

The reporter was enthusiastic, yet, in the next breath, melancholy at what apparently was a "faithful reproduction" of the passing of a native race, of the "…red race fleeing from destruction wrought by whites".

Today,

those raised on the "authenticity" of films and television can scarcely

comprehend what a live display of this kind must have meant to Europeans

of the late 19th century. Speaking of a simulated Sioux attack on an

immigrant wagon train, part of the daily show in Naples, the reporter

for il Paese continued:

| No description can convey the effect of an authentic mounted charge by Indians, this folk who here show us a few meagre scenes from a life that until a few years ago was theirs to lead untrammelled. |

Buffalo

Bill Cody had brought a kind of time machine with him. He had opened

a window and given a privileged few a chance to look out and glimpse

something very rare: an authentic reproduction of a way of life played

for them by the very people who had led it. The window would soon close

and the players would become anachronisms and caricatures of themselves.

Then, generations of imitators and made–up distortions of "cowboys

and Indians" would follow. For a fleeting moment, however, the citizens

of Naples and other European cities got a chance to see the real thing.

Confederate flag, Neapolitan culture (2)

If you let your eyes wander along the display of flags mounted over the entrance to one seaside restaurant in particular down at the small port of Mergellina, you can test your vexillological prowess: Let’s see—that one is Brazil; there’s France…hmmm, the Scandinavian ones are confusing, and did you ever notice that Belgium is the same as Germany except on its side, but not quite? Say, they even have the new European flag up and waving. Wait, what’s that? A blue St. Andrew’s cross with white trim, 13 stars arrayed within the bars of the cross, all on a field of red…a Confederate flag.

Well, maybe they just found one and put it up because it’s a nice design. Not quite. It’s up there for the same reason that it is painted on the entrance to a bar not far from the restaurant, a club with the delightfully oblivious–to–American–idiom name of “Southern Bull”. The bull, in this case, is to be understood not as in “What a bunch of…,” but rather as in “raging,” one fine, prime specimen of which species is superimposed, snorting and swollen with pride, on the flag, itself—a raging bull from the south (of Italy, of course). Similarly, if enough fans to constitute a rooting section ever show up again at a Naples home game at the San Paolo soccer stadium, you will see a number of such flags fluttering in the breeze. These will have an interesting variation: the circular logo of the Naples team is positioned at the center of the cross and inscribed—in English!—around the perimeter of that logo is the phrase, “The south shall rise again.”

You don’t

need a degree in cross-cultural anthropology to figure this one out.

As losers in their own war against their own north 140 years ago, Neapolitans

identify with the defeated south in the US Civil War. They watch “Gone

With the Wind,” and they know who the good guys are. Unlike some

places in the southern US today, there is no doubt in Naples as to whether

that flag stays up or comes down. It stays up—and they just ain’t

whistlin’ ‘o sole mio.

Castrati

Well,

Will, we'll worry about your grammar later. First, let me tell you a

few things about unkind cuts, which, in your frenzied groping for superlatives,

you seem to have overlooked. What follows is not for the squeamish,

so gird your loins. Wait, belay my last. Forget your loins. By the time

I'm through, you'll never want to hear the word "loins", again.

Well,

Will, we'll worry about your grammar later. First, let me tell you a

few things about unkind cuts, which, in your frenzied groping for superlatives,

you seem to have overlooked. What follows is not for the squeamish,

so gird your loins. Wait, belay my last. Forget your loins. By the time

I'm through, you'll never want to hear the word "loins", again.

In his short reign (1585-90) as Pontiff, Pope Sixtus V (no kin to Fiftus VI) strengthened the financial policies of the Roman Catholic Church, straightened out its administration, finished St. Peter's Dome and more or less geared up the Church for the Counter-Reformation. He is also known for his no nonsense interpretation of 1 Corinthians, XIV, 34, in which Paul tells us: "Let your women keep silence in church; it is not permitted unto them to speak." The Pope, hard-liner and tone deaf, reckoned that singing was just a funny kind of speaking, anyway, so let's not let them sing, either. This led directly to the wholesale revival of the ancient and hideous practice of castration.

Being a choir master in those days was frustrating. The so-called "white voice" of children was a natural in church; it was surely the same high, pure, innocent voice as that of Heaven's own puffy-cheeked little cherubs and angels. But it still had to be trained, and no sooner did you get a young boy finely tuned and able to sing well, than Nature let him have it with a jolt of testosterone, giving him pimples and otherwise priming him for years of anxiety-filled social gaming, a dubious trade-off every now and then for brief spurts of intense pleasure. More to the case in point, it also sent his voice cracking and plummeting into the octaves below and sent the choirmaster, in his own dogged imitation of Sisyphus, wearily back for another kid, never ever winding up with a well-trained strong adult soprano singer. Women, as we have noted, were out of the question.

There were two ways to get post-pubescent male sopranos. The first was to train the "falsetto" voice, that bit of vocal chord contortionism which puts out that high, breaking voice associated today mainly with certain kinds of folk music, such as the Swiss yodel or American country music. "Falsetto", in Italian, is a diminutive of "false", and that is just how the public felt about it: a false little voice, a scrawny and brittle stand-in for the real thing, completely unacceptable to music-lovers.

Enter a solution which made the purists happy, putting them, uh, on the cutting edge of Baroque vocal technology. It was perversely called "natural falsetto". It was, in fact, the castrato. The eunuch. Beginning in the late 1500's, young boys were routinely mutilated in this fashion to keep their voices from changing, so that they might better "make a joyful noise unto the Lord".

The "white voice" of the subsequent adult male soprano was so remarkable that with the beginnings in the early 1600's of opera and music performed outside the church, the castrato soared to secular prominence. For two-hundred years they were the most sought-after of voices on European stages. They were wondrous: such was the dynamic, abstract quality of their virtuoso soprano and contralto voices, that they were often said to be more instrumental than vocal. They were intensely trained (loners and social outcasts that they were, they had little else to do but practice) and so flexible that they could warble along with the birdlike flights of flutes and clarinets. Today, we might describe such voices as "electronic". (Even their critics described them as heavenly: "The shrill celestial whine of eunuchs" was a favorite castratophobe jibe of the day.) Generally, however, they were popular—so much so that they often moved the public to hysteria. The great Loreto Vittori (1604-1670) used to stoke the folks to such white-hot passion with his singing that they often threw open their garments! Once, while he was singing at a college of Jesuits, a mob stormed the place to hear him and sent the cardinals and nobles fleeing. (No doubt, it was Baroque Teenager doing all this ranting and raiment rending, returning home that evening to hear Baroque Parent lecture on the evils of modern music: "Do you think your mother and I went crazy like that over Palestrina's madrigals? Now there was music!")

Because of the greater lung capacity and physical bulk of males, the castrato soprano voice was also incredibly powerful, much more so than its feminine counterpart. Napoleon had a thirty-voice castrato choir at his coronation in 1804 and they attacked the Tu es Petrus with a fortissimo that drowned out a nearby harp orchestra and three-hundred member choir of "normal" voices.

This illegal but tolerated practice was widespread in Italy, and though people feigned feelings of guilt once in a while, most of the time they just looked the other way. Italian cities accused one another of being hotbeds of evil surgery, but it was Bourbon Naples of the mid-1700's—entrepreneurial even back then—which was the castrato capital of Europe. Its four conservatories and opera house also made it the opera capital of Europe. This combination produced a thriving black market in eunuchs. Hustlers would buy children or find orphans, pay for the operation and music lessons and hope to multiply their investment over the long term if the child grew up to be a big opera star.

It

was changing musical tastes—nineteenth-century romanticism's dedication

to real human passion—rather than moral qualms, which brought

about the decline of the strange, sad figure of the castrato. By the

early decades of the 1800's they were no longer in demand, although

an occasional aberration would turn up, such as Wagner (in 1880!) originally

insisting on a male soprano for the role of Klingsor in Parsifal. In

1903 Pope Pius X finally and officially forbade the "cultivation" of

the white voice. Again, moral qualms apparently played no part; Pius'

edict declared that much contemporary church music of the day was simply

too modern, including such massive orchestral works as Verdi's Requiem.

He wanted a return to the simplicity of the Gregorian chant. With

that, the castrato faded into obscurity, even within the confines of

the Roman Catholic church. The last castrato in the Vatican Chapel was

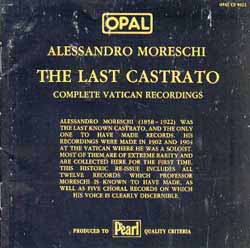

Alessandro Moreschi (1858-1922). There is even a recording* of him (photo,

CD cover), witness to one of the more bizarre sidelights in the history

of music.

It

was changing musical tastes—nineteenth-century romanticism's dedication

to real human passion—rather than moral qualms, which brought

about the decline of the strange, sad figure of the castrato. By the

early decades of the 1800's they were no longer in demand, although

an occasional aberration would turn up, such as Wagner (in 1880!) originally

insisting on a male soprano for the role of Klingsor in Parsifal. In

1903 Pope Pius X finally and officially forbade the "cultivation" of

the white voice. Again, moral qualms apparently played no part; Pius'

edict declared that much contemporary church music of the day was simply

too modern, including such massive orchestral works as Verdi's Requiem.

He wanted a return to the simplicity of the Gregorian chant. With

that, the castrato faded into obscurity, even within the confines of

the Roman Catholic church. The last castrato in the Vatican Chapel was

Alessandro Moreschi (1858-1922). There is even a recording* of him (photo,

CD cover), witness to one of the more bizarre sidelights in the history

of music.

[Interestingly, there are male sopranos that are not eunuchs. They are termed "sopranista" and composers such as Rossini wrote parts for them after the real castrato went out of fashion. Their vocal range is apparently due to some hormonal anomaly. They still perform today; a prominent such performer is Simone Bartolini, an Italian who specializes in the Baroque repertoire.]

*"Moreschi,

The Last Castrato." Pearl Opal CD 9823. Pavilion Records, Wadhurst,

England.

At

9 o' clock this morning all was quiet. An hour earlier, hordes of very

tired people were still driving around, generally wending their way

back home after having stayed up all night to see in the New Year. There

were two large public parties sponsored by the city in Naples last night:

one was in Piazza Plebiscito, the spacious square in front of the royal

palace; the other was in the recently reopened Piazza Dante about a

mile from the first one. The celebration at Piazza Plebiscito was the

one they have every year—fireworks, music, lots of year–end

noise. The festivities at Piazza Dante, however, were billed as the

celebration “for intellectuals,” whatever that is supposed

to mean. Perhaps they stood around and discussed what kind of values

are manifested by blowing off fingers with shoddy, homemade “cherry

bombs”. (In Naples, however, they use the whole orchard.)

At

9 o' clock this morning all was quiet. An hour earlier, hordes of very

tired people were still driving around, generally wending their way

back home after having stayed up all night to see in the New Year. There

were two large public parties sponsored by the city in Naples last night:

one was in Piazza Plebiscito, the spacious square in front of the royal

palace; the other was in the recently reopened Piazza Dante about a

mile from the first one. The celebration at Piazza Plebiscito was the

one they have every year—fireworks, music, lots of year–end

noise. The festivities at Piazza Dante, however, were billed as the

celebration “for intellectuals,” whatever that is supposed

to mean. Perhaps they stood around and discussed what kind of values

are manifested by blowing off fingers with shoddy, homemade “cherry

bombs”. (In Naples, however, they use the whole orchard.)