©

2004 Jeff Matthews & napoli.com

Gaiola

This tiny isle,

Gaiola, is but a few yards from shore, just east of Cape Posillipo. It

is the site of an ancient navigators' shrine to Venus as well as near

the site of the few Roman ruins of "the sorcerer's house"

where the poet Virgil, also renowned as

a magician, is said to have taught. In this picture, it is watched by

a small statue of St. Francis. This tiny isle,

Gaiola, is but a few yards from shore, just east of Cape Posillipo. It

is the site of an ancient navigators' shrine to Venus as well as near

the site of the few Roman ruins of "the sorcerer's house"

where the poet Virgil, also renowned as

a magician, is said to have taught. In this picture, it is watched by

a small statue of St. Francis.

Gaiola

has two small neighbor islets. The modern house on it is abandoned and,

at last notice, the isle and house were up for sale—with no takers!

Over the centuries, Gaiola has developed a reputation of being haunted

and there are many rumors about the misfortunes —including violent

death— that befall those who inhabit it. These rumors, obviously,

were not started by real estate agents.

Greek

Orthodox Church

In 330 a.d. a Christian

convert built a Christian city to replace the old and pagan Rome. His

—Constantine the Great's— faith would soon be proclaimed

the official religion of the Roman Empire. The bad news would be that

he had inadvertently made it possible for that Empire to be divided

in two, sundering its church right along with it. In 330 a.d. a Christian

convert built a Christian city to replace the old and pagan Rome. His

—Constantine the Great's— faith would soon be proclaimed

the official religion of the Roman Empire. The bad news would be that

he had inadvertently made it possible for that Empire to be divided

in two, sundering its church right along with it.

There were

organizational problems among early Christians. Should the bishops of

Rome, Alexandria, Ephesus, Antioch and Constantinople all have equal

authority? Or should Rome dominate, based on its imperial political

status and the special history of the Roman church —that is, its

founding by the apostle Peter? This squabble was joined by divisive

theological ones: debates on the nature of God, Christ and the

Trinity.

When the

Western Roman Empire fell in 476, the Western church bided its time

with organizational matters. The lack of imperial authority actually

led to a strengthening of the Roman church, since it took over a number

of civic functions it might never have had to, if there had remained

in place a true imperial bureaucracy in the West.

On the

other hand, Constantinople viewed itself as the natural continuation

of Empire. The emperor was "High Priest and King," God's emissary on

earth and the head of the Church. He could not owe allegiance to anyone

else, much less a bishop of the Western church. In the years between

500 and 800, Constantinople became by default a Greek State: the

Byzantine Empire. Latin ceased to be the official language of government

and was replaced by Greek, accentuating the religious differences and

accelerating the separation of the Greek and Roman Churches.

The reestablishment

of a Western Empire by Charlemagne in 800 meant that there were two

strong competing Christian empires. In the two centuries that followed,

while having to relinquish Asia Minor and the Middle East to the surge

of Islam, the East remained powerful, spreading to carry Orthodox (meaning

"Right Faith") Christianity to Russia. The Western Empire carried its

faith to the north and to the British Isles. In spite of seven ecumenical

conferences held over the centuries to resolve theological differences,

the two churches finally excommunicated each other in 1054. This was

called the great Schism and effectively destroyed the integrity of the

Christian Church.

At present

the Orthodox Eastern Church has approximately 150 million followers,

and is the second largest Christian denomination in the world. It is

composed of 15 self-governing churches worldwide, such as, among others,

the Russian Orthodox Church, the Cyprus Orthodox Church and the Greek

Orthodox Church.

Greeks

and Naples have always had a special relationship. First, of course,

the city was founded by the Greeks. But even later, when Naples and

Greece, itself, were part of the Roman Empire, Greek remained a widely

spoken language in Naples. When the West fell to the Goths, Naples fell

with it, but was quickly retaken by the Byzantine Empire. Byzantine

power surged and ebbed in Southern Italy in the sixth, seventh and eighth

centuries, but Greek influence in Naples remained strong. Even after

Charlemagne refounded the Western Empire, southern Italy was not part

of it. In spite of the growing hostility between the Eastern and Western

branches of Christianity, there were Eastern Churches and monasteries

all over the south, Naples included. After the Schism, Orthodox rites

were still commonly held in and around Naples, and there was even a

Greek monastery in use here until the Counter-Reformation in the 17th

century. Visitors to the Naples Cathedral will still find a double baptistery

inside, one for Roman Catholic rites and the other for Greek rites.

Also, for reasons obscured by time, a benediction by a Greek Orthodox

priest is considered particularly auspicious by otherwise quite Roman

Catholic Neapolitans. It is, according to popular custom, one of the

ways in which the so-called malocchio, the 'evil eye,' can be

warded off.

The Greek

Orthodox Church in Naples is on Via S. Tommaso Aquino in the downtown

area. It was founded as the "Confraternity of Greeks Resident

in the City of Naples" almost immediately after the fall of Constantinople

in the 15th century by Greek refugees from that event.

In 1518,

a Byzantine prince, Tommaso Assanios Paleologos, paid for the construction

of the chapel. The text of the Greek rites were defined in 1760 by a

decree of the Bourbon Kingdom of Two Sicilies.

The status of the church, as defined by the Bourbons, was accepted by

the new Italian State after the unification of Italy in the 19th century.

The members

of the confraternity vote by secret ballot on how to distribute income

from offerings and the few properties that the Church owns in Naples.

Monies are used for philanthropic and educational purposes, as well

as to pay those who work for the church. Such income has helped to create

an elementary school for Greek children as well as children of mixed

marriages. There is also an auditorium for social gatherings.

The church,

itself, is small and intensely spiritual. The silver icons have an overpowering

presence and are close enough to touch —indeed, they are meant

to be touched. Personally, I first noticed the music. Byzantine chants

are related at some point in a higher dimension to their Gregorian cousins

in the Western church, but a thousand words detailing untempered minor

scales, mysterious quarter-tones and the Eastern passion for the ornamental

quiver in the voice would do as little justice to the music of Byzantium

as my other words have done to the religion. You will have to go hear

and see for yourselves.

Plebiscito,

Piazza; Naples Prefecture; San Francesco di Paola

Piazza Plebiscito

is the largest square in Naples. It is bounded on the east by the Royal

Palace and on the west by the church of San Francesco di Paola (photo,

left) with its impressive colonnades extending to both sides.

In the first years of the 19th century, the King of Naples was Gioacchino

Murat (Napoleon's brother-in-law). He started to build, as a bit

of imperial splendour, a Romanesque forum in the square. When Napoleon

was finally dispatched, the Bourbons were restored to the throne of

Naples. Ferdinand I continued the construction but was so grateful at

having his kingdom back that he made the finished product into

church you see today. He dedicated it to San Francesco di Paola, who

had stayed in a monastary on this site in the 16th century. The

church is reminiscent of the Pantheon in Rome. The façade

is fronted by a portico resting on six columns and two Ionic pillars.

Inside, the church is circular with two side chapels. The dome is 53

metres high. Piazza Plebiscito

is the largest square in Naples. It is bounded on the east by the Royal

Palace and on the west by the church of San Francesco di Paola (photo,

left) with its impressive colonnades extending to both sides.

In the first years of the 19th century, the King of Naples was Gioacchino

Murat (Napoleon's brother-in-law). He started to build, as a bit

of imperial splendour, a Romanesque forum in the square. When Napoleon

was finally dispatched, the Bourbons were restored to the throne of

Naples. Ferdinand I continued the construction but was so grateful at

having his kingdom back that he made the finished product into

church you see today. He dedicated it to San Francesco di Paola, who

had stayed in a monastary on this site in the 16th century. The

church is reminiscent of the Pantheon in Rome. The façade

is fronted by a portico resting on six columns and two Ionic pillars.

Inside, the church is circular with two side chapels. The dome is 53

metres high.

On the north side

of the square is the Naples Prefecture (photo, right). It is on the

site of the old Convent of the Holy Spirit built in the early 1300s.

The clearing away of the monastery was part of the general campaign

by the French during the Napoleonic decade under Murat in Naples (1806-1815)

to, one, supress monastic orders and, two, rebuild the space in front

of the Royal Palace. This building was started in 1810, suspended when

the Bourbons returned to the throne of Naples in 1815, and then continued,

following the original plans. It is a "twin" of Palazzo Salerno,

the building facing it from directly across the square. That building

houses the Regional Military Command and, in spite of the identical

appearance, is older; it was built in 1775 by the Bourbons to house

a batallion of military cadets. Palazzo Salerno, however, was

then redone to look like the newer one in the photo as part of

the French and then Bourbon plan to rebuild the square. Actually, the

Prefecture is better known to most because it is adjacent to the Gambrinus

cafe, a favorite haunt of poets and musicians during the late 1800s

and early 1900s and, today, a favorite tourist attraction. On the north side

of the square is the Naples Prefecture (photo, right). It is on the

site of the old Convent of the Holy Spirit built in the early 1300s.

The clearing away of the monastery was part of the general campaign

by the French during the Napoleonic decade under Murat in Naples (1806-1815)

to, one, supress monastic orders and, two, rebuild the space in front

of the Royal Palace. This building was started in 1810, suspended when

the Bourbons returned to the throne of Naples in 1815, and then continued,

following the original plans. It is a "twin" of Palazzo Salerno,

the building facing it from directly across the square. That building

houses the Regional Military Command and, in spite of the identical

appearance, is older; it was built in 1775 by the Bourbons to house

a batallion of military cadets. Palazzo Salerno, however, was

then redone to look like the newer one in the photo as part of

the French and then Bourbon plan to rebuild the square. Actually, the

Prefecture is better known to most because it is adjacent to the Gambrinus

cafe, a favorite haunt of poets and musicians during the late 1800s

and early 1900s and, today, a favorite tourist attraction.

Until

quite recently, the square had been allowed to fall victim to an urban

decay of sorts; i.e. it had turned into one gigantic parking lot. As

part of the general plan to make the city more enjoyable for residents

and visitors alike, Piazza Plebiscito was cleared and restored by the

city government in the early 1990s. It is now one of the big tourist

attractions in the city, a good place to stroll and get your bearings.

The square hosts various celebrations during the year, from rock concerts

to annual New Year's Eve festivities. It is also the site of periodic

displays of "installation art". The name

of the square honors the 1860 plebiscite that ratified the unification

of Italy.

Mortella,

la (1); William Walton

Set foot in La Mortella, the gardens of the late

English composer, William Walton, located on the island of Ischia in

the Bay of Naples, and you will know what Francis Bacon meant

when he said: "God Almighty first planted a garden. And, indeed, it

is the purest of human pleasures." Set foot in La Mortella, the gardens of the late

English composer, William Walton, located on the island of Ischia in

the Bay of Naples, and you will know what Francis Bacon meant

when he said: "God Almighty first planted a garden. And, indeed, it

is the purest of human pleasures."

The composer

and his wife, Susana, settled on Ischia in the early 1950s. There, one

of the great musical spirits of our age set about to continue his life's

work. His wife set about her own life's work, as she says, of building

"a garden for an artist." It was to be a place of serenity, something

to offset the turmoil within the composer, a place that would invite

him to look not just out at the garden, but within himself. That is

a tall order, indeed, when you start with a rocky, waterless gully covered

with a bit of evergreen holm oak and some dying chestnut trees.

The transformation

from scrubby rock quarry to enchanting blend of rock garden and tropical

rain forest was planned by the distinguished landscape architect, Russell

Page, and begun in 1956. His designs evolved through 1983, but the work

is still going on under the "green fingers" of Lady Walton, for whom

"…gardens reflect our dreams and aspirations… they are our

fantasies." In that spirit, over the years, La Mortella, has

been magically transformed — but, delightfully, not tamed. You

will not find the obedient and trimmed vegetation of, say, a Japanese

garden. La Mortella looks more like a forest ruled over by a

totally benevolent but mischievous goddess who simply can't be bothered

to pick up after herself!

Of course,

the art of true helter-skelter is to plan it carefully. Thus, the paths

curve at all the right places, and the terraces offer evershifting perspectives;

when viewed from where Walton, himself, must have paused from his work

to look out, fountains are arched by trees, and this puzzle of vegetation

suddenly solves itself and fits together.

At La

Mortella you find everything from the extravagant pot-bellied Chorisia

speciosa tree from Argentina (where they, appropriately, call it

"the drunkard") to purple-pink geraniums from Madeira; ferns from the

Canary islands and dwarf rosemary from the gardens of the University

of Jerusalem; honey-suckles from South Africa, the soft green-yellow

petals of California tulip trees, water lilies, jasmine, orchids, bright

green Thalia and —as you ascend—even the lotus, set off

meditatively alone in its own pond at the highest point of La Mortella.

Water has been brought in, not just to nourish the gardens, but to provide

for the Alhambra-like presence of fountains and pools, the sounds of

which remind us that even here in the presence of the composed music

of man, nature has its own music.

All that,

however, is just half the story. La Mortella exists as part of

the William Walton Foundation, dedicated in 1989 as a centre of the

performing arts, a place for young composers and artists to study and

perform, with "special reference" to the music of William Walton. (The

composer passed away in 1983.) Here you will find not only the Waltons'

home, but rehearsal rooms, as well. Each year, auditions are held to

select participants in a master class, a month-long session of rehearsals

culminating in performances open to the public.

At La

Mortella there is also a museum, where you can browse among

memorabilia from Walton's life as a composer, as well as watch a film

on his life and work. And there is a tea-shop, where you can sit and

simply look out over the gardens—and if that is all you do, it's

still reason enough to go.

Spanish

Quarter

The main

shopping thoroughfare in modern Naples is via Roma, a

name thatmany Neapolitans reject in favor of the original name, via

Toledo, named for Don Pedro di Toledo, the Spanish viceroy of Naples

from 1532 to 1553. He was one of the most notable in a long line of

representatives of the Spanish throne who ruled Naples

between 1500 and 1700. Don Pedro is the viceroy who began the great

Spanish reshaping of Naples, changes that extended into every aspect

of life in the city, from the building of new living quarters to the

enlarging of port facilities and shoring up of city fortifications.

The Spanish renovation of Naples was precisely that—a renewal,

one that cast Medieval and Renaissance Naples in a modern sixteenth-century

mold, which would then carry the city directly into the age of the Baroque.

Via Toledo

begun in the late 1530s, was the centerpiece of one of the most

impressive projects undertaken by Don Pedro: the construction of an

entirely new popular quarter of the city, today called, simply,

The Spanish Quarter—or, by many Neapolitans, the Casbah(!),

thus recalling the Moorish influence in the history of the builders.

The main street, via Toledo (bounding the Spanish Quarter at the bottom

of the above map) was laid out to lead north from what is now the

square in front of the Royal Palace.

In the 1530s there was not yet a Royal Palace, but the square itself

was adjacent to the large complex that included the Maschio

Angioino and the living quarters of the Viceroy; thus, it was a

logical place to start a new main road. Via Toledo ran along the line

of an earlier city wall and was actually intended to supplant that fortification,

literally breaking the confines of the medieval city and extending it

up the slope of the hill of San Martino,

a natural barrier. Via Toledo then continued on to Largo Mercatello,

later, under the Bourbons, to be known as Foro Carolina, and

today as Piazza Dante.

The Spanish

Quarter thus starts at the beginning of via Toledo and consists

of dozens of symmetrical square blocks, with the east-west streets

running up the slope of San Martino. There are about a dozen of these

streets between the Palace and the section of Naples called Montesanto.

They lead up the slope from via Toledo and are then crossed by

a number of secondary parallel streets, each one at a progressively

higher level on the slope. The effect is of a chessboard of perfect

little squares built on the side of a hill. A great number of stairways

are built into the east-west streets to help the pedestrian climb the

slope.

The Spanish

built a number of villas and residences on the spacious sites fronting

the new via Toledo. Many of these buildings are still standing and recognizable

even through centuries of overlaid architecture. The Spanish expansion

also included the area on the other side of via Toledo and running

north towards Piazza Dante. Thus, one finds the Church of

San Giacomo degli Spagnoli on the east side of via Toledo on

what is now Piazza Municipio. The entire

area of the Spanish Quarter in the first few years of its existence

was, indeed, a "Spanish Quarter," for it was in these houses that many

of the 6,000 Spanish soldiers quartered in Naples in the mid-sixteenth

century found accommodations before moving into a central barracks in

the 1650s.

The area

behind the main street still contains some Baroque churches from the

late 1500s and early 1600s. The most famous of these is the Church of

Santa Maria della Concezione a Montecalvario, from the year 1589.

This church was also the site of an orphanage sponsored by the congregation

and which was in operation until the end of the 1800s. The church was

rebuilt in the 1720s and has a central space with side chapels and a

dome.

The residences

in the Spanish Quarter are four and five stories high, quite an accomplishment

for 1600. (Even as late as the 1870s, Mark Twain commented on the “tall

buildings of Naples”.) The blocks were an enormous departure from

the winding clutter of medieval cities and are, perhaps, the first example

of modern urban planning in Europe. "Urban planning" should, realistically,

not be understood here in the benevolent twentieth-century sense of

providing the poor with a decent place to live, however. [For a separate

item on urban planning in Naples at the beginning of the 20th century,

click here.] An age of absolute monarchy

was concerned less with such things than it was with its own physical

security.

Here, one

does well to recall Lewis Mumford’s remark that the clearing

away of the small winding medieval streets of Paris by Napoleon III

in the mid-nineteenth century did away with the last physical

barrier which protected the common citizen from the power of the absolute

state. Such was the case in Naples: a long rebellious nest of medieval

clutter into which the King’s soldiers ventured at considerable

risk was made somewhat more manageable by the introduction of broad

straight roads that were easy to patrol. The centuries have by-passed

that concept somewhat, for it is now the Spanish Quarter, itself, that

has acquired a foreboding reputation as a section of Naples where a

stranger does not enter without some concern.

[See

her for another item on Spanish buildings in Naples.]

Noodles

I don't know that

this is the world's greatest pasta shop, but I like it. Pasta comes

as spaghetti, macaroni, fettuccini, tagliatelle,

penne, rigate, vermicelli, capellini, anelli,

spirali, fusilli, maltagliatti, et noodle cetera

—and those are just some of the common, generic Italian noodles

in the present tense. Neapolitan conjugations include—but are

not limited to (as pasta-loving legal fleagles like to say) —ziti

and paccheri.) They come in red, green, white, and even the off-brown

of (ugh!) whole-wheat health-food pasta. Also, they are stubby, skinny,

straight, wavy, cork-screwy, and shaped like a torus, also known as

an "anchor ring" (or "donut" to non-mathematicians). Attempts to create

a stable double-torus noodle have thus far been unsuccessful. (See Dente,

Al. "Getting a Handle on a Trivial Tubular Neighborhood" in the Journal

of Pasta and Topology.) I think this shop has all of them. I don't know that

this is the world's greatest pasta shop, but I like it. Pasta comes

as spaghetti, macaroni, fettuccini, tagliatelle,

penne, rigate, vermicelli, capellini, anelli,

spirali, fusilli, maltagliatti, et noodle cetera

—and those are just some of the common, generic Italian noodles

in the present tense. Neapolitan conjugations include—but are

not limited to (as pasta-loving legal fleagles like to say) —ziti

and paccheri.) They come in red, green, white, and even the off-brown

of (ugh!) whole-wheat health-food pasta. Also, they are stubby, skinny,

straight, wavy, cork-screwy, and shaped like a torus, also known as

an "anchor ring" (or "donut" to non-mathematicians). Attempts to create

a stable double-torus noodle have thus far been unsuccessful. (See Dente,

Al. "Getting a Handle on a Trivial Tubular Neighborhood" in the Journal

of Pasta and Topology.) I think this shop has all of them.

If all

that is just "noodles" to you, then maybe you don't deserve this information.

But if you are familar with the bizarre very-pre-surrealist works of

Giuseppe Arcimboldi (1527 -1593), who specialized in painting human

figures out of edibles, you will be pleased to know that his spirit

is alive and well in Naples. Mr. Noodle Head (photo) and other similar

renditions of the human head are to be found in a fascinating pasta

shop on via Benedetto Croce, a few yards after entering the old

city from the direction of Santa Chiara (approximately,where #6 is on

the map of the historic center.)

Christianity,

early; San Pietro ad Aram

Paleo—Greek

for "ancient"— means different things in different contexts.

When used in the term "paleo-Christian" in this part of Italy, it generally

refers to Christian relics and sites dating back to well before the

year 1000. Naples has a number of these to offer, though, as is the

case with many ancient things, they have been covered over by the handiwork

of later centuries.

To begin

with, the catacombs of San

Gennaro, on the way up to Capodimonte, are the most extensive and

interesting examples of early Christian cemeteries to be found in Italy

south of Rome. Also, a number of churches in Naples that now seem 'merely'

medieval have their origins in the middle of the first millennium well

before the beginning of the great age of church building. For example,

the church and vast monastic complex known as San

Gregorio Armeno located on the street of the same name goes back

to the eighth century when refugees from the iconoclast controversies

shaking Byzantine Christendom in the east fled to Italy, in this case

bringing with them to Naples the remains of their patron, Gregory of

Armenia.

(The photo, left, shows the entrance to San

Michele Arcangelo a Morfisa, a small Byzantine

church that housed the Basilian monastic order. It is now incorporated

into the massive church of San Domenico

Maggiore, but was built centuries earlier.)

Another relic of early Christianity is hidden within the Church of San

Paolo Maggiore on via dei Tribunali, one of the three original east-west

thoroughfares of the Greek city of Neapolis. The modern church stands

above a spectacular stairway, and, in the form you see today, was built

at the end of the sixteenth century. However, it was erected on the

ruins of a preexisting eighth-century church built to celebrate a Neapolitan

sea victory over Saracen invaders. That church, by the way, was built

on the site of --and even incorporated part of the structure of—a

Greek temple dedicated to Castor and Pollux. Also, the Church of Santa

Maria Donnaregina on vico Donnaregina is on the site of an ancient

monastic complex dating back to the eighth century.

The best-known

example of a paleo-Christian church in Naples, of course, is

in the Duomo, the cathedral of Naples,

itself. Incorporated in the cathedral is the Santa Restituta basilica,

which used to be a church in its own right, built in the 6th century.

Its present three aisles divided by 27 antique columns are what is left

of the original church after the main body of the massive cathedral

was built around it, so to speak, in the 13th century. They say that

Santa Restituta was a young African woman, who, because she was a Christian,

was abandoned to the sea on a boat set ablaze. The fire, however, died

out and she was miraculously able to put ashore on the island of Ischia.

In the eighth century her remains were brought to the church in Naples,

which then took her name.

Still

on via Duomo and not far from the Cathedral is the church of

San Giorgio Maggiore. Its proximity to the Duomo may account for the

neglect that this house of worship has suffered over the centuries.

San Giorgio Maggiore is one of the oldest churches in the city; indeed,

it is truly “paleo-,” one of those churches built in the

early centuries of Christianity in Italy and that disappeared or were

covered over by newer buildings in the great age of cathedral building

after the turn of the millennium. Still

on via Duomo and not far from the Cathedral is the church of

San Giorgio Maggiore. Its proximity to the Duomo may account for the

neglect that this house of worship has suffered over the centuries.

San Giorgio Maggiore is one of the oldest churches in the city; indeed,

it is truly “paleo-,” one of those churches built in the

early centuries of Christianity in Italy and that disappeared or were

covered over by newer buildings in the great age of cathedral building

after the turn of the millennium.

You enter

the church from a small square on the north side of the building, take

a few steps and, at first, get the impression that you are in just another

17th–century Neapolitan church. Yet, when you turn, you see that

your few steps have taken you through a primitive apse of unadorned

masonry (photo), the small columns and vaulted dome of which are obviously

much older than the rest of the building. Indeed, they are—by

a thousand years. The original San Giorgio Maggiore is from about the

year 600 a.d. and all that is left of it is that tiny bit that is so

easy to overlook as you go inside.

The present

large church is from the 1600s when the decision was made to raze the

older building, incorporating a small token of it into the newer church.

Then, much of that newer building was subsequently demolished during

the urban renewal of Naples in the late 1800s when via Duomo—the

major road outside the church—was widened.

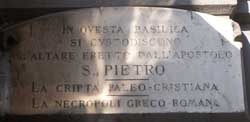

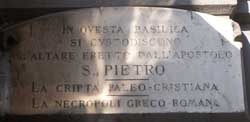

One

of the most fascinating examples of early Christianity in Naples is,

however, one which for some reason doesn't get a lot of press or tourist

attention. Yet, if what tradition says about this church is true, then

it is most certainly the site of the earliest instance of Christian

worship in Naples—or, for that matter, one of the earliest

anywhere. Hidden away off of Corso Umberto near Piazza Garibaldi

is the Church of San Pietro ad Aram. "Pietro," of course, refers

to the apostle Peter, the "rock" upon whom Christ said He would found

His church. "Aram" is the biblical name for parts of Mesopotamia and

Syria. The word is still found today in reference to the Aramaic language

of that region. Neapolitan tradition (and the plaque on the outside

of the church [photo]) says that Peter left Antioch on his way to Rome

nine years after the death of Christ. He stopped in Naples and held

a worship service on a rudimentary make-shift altar. Twenty centuries

later, beneath the countless changes wrought during all those fleeting

human ages that we flatter with such names as Medieval, Renaissance,

Baroque, etc., that altar—again, according to tradition—is

still there. One

of the most fascinating examples of early Christianity in Naples is,

however, one which for some reason doesn't get a lot of press or tourist

attention. Yet, if what tradition says about this church is true, then

it is most certainly the site of the earliest instance of Christian

worship in Naples—or, for that matter, one of the earliest

anywhere. Hidden away off of Corso Umberto near Piazza Garibaldi

is the Church of San Pietro ad Aram. "Pietro," of course, refers

to the apostle Peter, the "rock" upon whom Christ said He would found

His church. "Aram" is the biblical name for parts of Mesopotamia and

Syria. The word is still found today in reference to the Aramaic language

of that region. Neapolitan tradition (and the plaque on the outside

of the church [photo]) says that Peter left Antioch on his way to Rome

nine years after the death of Christ. He stopped in Naples and held

a worship service on a rudimentary make-shift altar. Twenty centuries

later, beneath the countless changes wrought during all those fleeting

human ages that we flatter with such names as Medieval, Renaissance,

Baroque, etc., that altar—again, according to tradition—is

still there.

Is it true?

I haven't the slightest idea, but 2,000 years doesn't seem like such

a long time to me any more. After all, I can reach over and touch bits

and pieces of stone walls and buildings near my house that were put

in place 500 years before that. Traditions, however, do have other functions

than simply being true; they serve as a means to bring religious and

social values into focus, and they help us appreciate our past and evaluate

what we believe. In those terms, true or not, the tradition surrounding

San Pietro ad Aram is a worthy one.

Croce,

Benedetto (2)

Villa Tritone in Sorrento

When

I heard the story the first time, it seemed too good to be true. Someone

mentioned to me Raleigh Trevelyan's book Rome'44, The Battle for

the Eternal City, in which —according to my second-hand source—there

is mention of a daring commando raid up a seaside cliff in Sorrento

to save the anti-regime historian and philosopher, Benedetto Croce, from the clutches of the nefarious

Germans in WW2. Said Nazis were going to take Croce hostage and

force him to eulogize the philosopher of the regime, Giovanni Gentile,

who had just been assassinated. The raid was carried out by a paramilitary

force that included the son of Axel Munthe, a long-time Capri resident,

author, and builder of the mansion that bears his name on the island. When

I heard the story the first time, it seemed too good to be true. Someone

mentioned to me Raleigh Trevelyan's book Rome'44, The Battle for

the Eternal City, in which —according to my second-hand source—there

is mention of a daring commando raid up a seaside cliff in Sorrento

to save the anti-regime historian and philosopher, Benedetto Croce, from the clutches of the nefarious

Germans in WW2. Said Nazis were going to take Croce hostage and

force him to eulogize the philosopher of the regime, Giovanni Gentile,

who had just been assassinated. The raid was carried out by a paramilitary

force that included the son of Axel Munthe, a long-time Capri resident,

author, and builder of the mansion that bears his name on the island.

As with

most second-hand tellings of third-hand readings from those who know

someone who read the book, the story was a mish-mash, and without having

consulted Trevelyan's book, I am quite willing to give him the benefit

of the doubt that that is not quite what he said.

The most

obvious mess is the connection to Gentile. The relationship between

Croce and Gentile is (1) beyond the scope of this brief entry and (2)

beyond my own poor powers of historical deconstruction. I do know that

they founded a journal together in the 1920s but then went their separate

ways when Gentile drafted the "Declaration of Fascist Intellectuals".

Croce was an anti-Fascist and spent most of the 1930s and WW2 being

hounded by regime goons. As far as this episode is concerned, Gentile

was murdered in 1944 and Croce's flight from Sorrento took place in

September of 1943. So, that part of it is out, but the real story isn't

half-bad, either.

Crose deals

with the episode in question in a small volume that I have finally had

a chance to consult. It is entitled Quando l'Italia era tagiata in

due: estratti di un diario (When Italy was cut in two: Extracts

from a Diary) and contains daily entries from July 1943 through June

1944. The book (published by Laterza in Bari in 1948) is strangely out

of print but was recently reprinted as a photographic copy in a limited

edition by Mario Pane, the owner of Villa Tritone in Sorrento, the cliff-top

mansion where Croce was living when the episode occurred. Croce had

left his residence, the Palazzo Filomarino

della Rocca in the historic center of town, and gone to Sorrento

to get away from the Allied air-raids of Naples. He moved into the Villa

Tritone, a splendid building set on a cliff in Sorento, overlooking

the sea (see photo, above). He was—as he had been in Naples—watched

by the authorities, but house arrest in the Villa Tritone does

beat a bare-bones prison cell.

He originally

published these diary excerpts in his Quaderni della Critica

in 1946 and 1947 "to correct misconceptions already starting to appear"

in the popular press about what had happened in Italy during that period

when "only the south" was in the hands of a true Italian government;

that is, the Germans were still in control in the north and had even

founded their puppet Italian Fascist Republic of Salò.

In his

entry for August 5, 1943, Croce sadly notes the "horrible destruction"

of the venerable Church of Santa Chiara,

directly across the street from his home. On September 3, he notes the

Anglo-American invasion of Calabria from Sicily.

On September

8, Croce mentions the official surrender of Italy to the Allied Forces

in the south. [At that point, the new Italian head-of-state Pietro Badoglio

went on the radio to tell the citizenry that "the battle continues"—against

the Germans and Italian Fascists. Italy was thus plunged into a civil

war.] The Germans, of course, did not simply pick up and move north;

they fought a very bitter campaign back up the boot of Italy. Three

days after the armistice of September 8, the Germans entered and occupied

Naples, which Croce mentions in his diary for that day. Croce mentions

on September 12 the spectacular rescue of Mussolini from his prison

on Gran Sasso in the mountains of the Abruzzi by a glider-borne team

of German commandos under Otto Skorzeny.

Through

all of this, Croce's notes betray no great concern for his personal

safety. He ploughed ahead with his considerable intellectual output,

working on, say, the poetry of Dante at virtually the same time as the

Allies were blowing the bridge at Seiano, a few miles further in on

the Sorrentine peninsula. On September 13, Croce writes for the first

time that he has received anonymous notes threatening himself and his

family, also living at Villa Tritone. On the next day, he reports

that there is confusion in Sorrento—no German troops, no Anglo-American

forces, but a lot of die-hard Fascists roaming the streets. His advisors

tell him that he has to leave immediately. Germans—who can still

come over the hills from Salerno—or home-grown Fascists in Sorrento

might like nothing better than to take him hostage and use him for propaganda

purposes. Croce writes, "I said that there were practical and moral

reasons why I couldn't leave. I didn't want a flight on my part to incite

panic among the populace." On the other hand, he notes with distaste

the uses to which his name might be put by a regime that he has detested

for so many years.

Then, suddenly,

the next day's entry, September 15, is written on Capri. Croce recounts

the events of the previous evening, when a floating mine was found in

the waters below the Villa. Forces intent on taking him and his family

hostage may be setting the stage. The retreating Germans really may

come to take him, the way they have already taken other prominent Italian

civilians in Salerno as they retreated. He has to go—now.

Croce relents and agrees to be taken to Capri—firmly in Allied

hands—in a motorboat that has come from that island. He leaves

at nine in the evening with three of his daughters as well as with a

police commissioner from Capri and an English officer, both of whom

have come from the island to rescue him. Croce leaves his wife and one

daughter behind to gather up the few things they will need later. He

reports the next day that the boat sent back to Sorrento from Capri

to pick up his wife and daughter has turned back because of the rumor

that the Germans have already invaded the villa and taken the rest of

his family. That rumor turns out to be false and on September 17, the

same boat, with the same police commissioner, this time accompanied

by a "Major Munthe (the son of Axel Munthe)" returns successfully and

picks up his wife and daughter.

The next

day, he is questioned by an English officer for names of "dangerous

persons and Fascists" left in Sorrento. He says he is not about to start

doing what he has refused to do for so many years—collaborate.

Through the whole episode, Croce is deeply saddened—and it comes

through even in his low-key prose—that his nation is cut in two

and he clearly does not want to fuel the fires of acrimony and vendetta

by naming names.

Later in

the week, he writes, the Italian Fascist and German radio stations state

that "Croce and others, who have tried the patience of the regime, will

be severely punished." At that, the Allies broadcast the news that Croce

is safe on Capri. So, there was no great derring-do or cliff-climbing—unnecessary

since Villa Tritone has its own stairs down to a private boat

landing—but nevertheless, it's a very human drama.

San

Ferdinando (church)

The everchanging nomenclature of Neapolitan streets

and squares now calls it Piazza Trieste e Trento, but the square

at the Royal Palace end of via Roma

used to be Piazza San Ferdinando, a name that still defines that

entire area of the city. The area takes its name from the Church of San

Ferdinando, adjacent to the Galleria Umberto

and directly in front of the large fountain in the center of the square.

It is often the first church that visitors to Naples see when they walk

up past the San Carlo opera to have a look at Piazza

Plebiscito. The everchanging nomenclature of Neapolitan streets

and squares now calls it Piazza Trieste e Trento, but the square

at the Royal Palace end of via Roma

used to be Piazza San Ferdinando, a name that still defines that

entire area of the city. The area takes its name from the Church of San

Ferdinando, adjacent to the Galleria Umberto

and directly in front of the large fountain in the center of the square.

It is often the first church that visitors to Naples see when they walk

up past the San Carlo opera to have a look at Piazza

Plebiscito.

The plans

for the church were drawn up in 1622 by the Society of Jesus (the Jesuits), and the church was

opened in 1665 after some years of interrupted construction. It was

originally dedicated to St. Francis Xavier (San Francesco Saverio, in

Italian) friend of St. Ignatius Loyola and one of the members of the

first company of Jesuits. The interior of the church still displays

numerous works of art depicting the life and missionary activities of

St. Francis Xavier, including a —by today's ecumenical

standards—"politically incorrect" painting of The Triumph

of Religion over Heresy through St. Ignatius, St. Francis Xavier, St.Francis

Borgia and the three Japanese martyrs, while Mohammed is cast down with

the Koran. Some prominent works have gone missing over the centuries,

including a painting by Salvator Rosa, or have been moved to other premises

(such as a painting by Luca Giordano that is now at the Capodimonte

Museum). The church was rededicated to San Ferdinando when the Jesuits

were expelled from Naples in 1767. The façade of the church has

recently undergone restoration.

Madre

del Buon Consiglio

Perched on the hillside leading up to the Capodimonte

Palace and very visible from various quarters of Naples is the church,

Madre del Buon Consiglio. Interestingly, it is not nearly

as old as it looks. It was built in the years between 1920 and 1960

in imitation of St. Peter's in the Vatican. It houses a number of works

of art rescued from closed, damaged, or abandoned houses of worship

in the city. There is also a path leading down to the catacombs

of Naples. Legend has already attached itself to the church: the earthquake

of 1980 toppled the head of the statue of the Madonna from the top of

the church to the ground, where it crashed and lay inexplicably undamaged. Perched on the hillside leading up to the Capodimonte

Palace and very visible from various quarters of Naples is the church,

Madre del Buon Consiglio. Interestingly, it is not nearly

as old as it looks. It was built in the years between 1920 and 1960

in imitation of St. Peter's in the Vatican. It houses a number of works

of art rescued from closed, damaged, or abandoned houses of worship

in the city. There is also a path leading down to the catacombs

of Naples. Legend has already attached itself to the church: the earthquake

of 1980 toppled the head of the statue of the Madonna from the top of

the church to the ground, where it crashed and lay inexplicably undamaged.

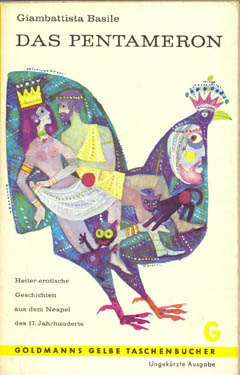

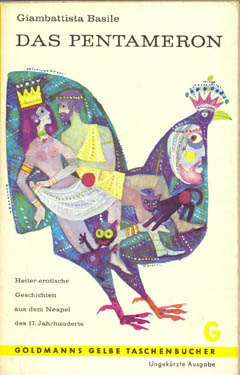

Basile,

Giambattista (1575-1632) and The Tale of Tales

European

nation states are now so well grounded in their respective national

languages that we often overlook what a vibrant history many non-standard

languages —"dialects"— have. Perhaps the recent (1976)

granting of linguistic autonomy in Spain to three minority languages

—Galician, Catalonian, and Basque— is a sign of some

sort of backlash in Europe against overbearing language hegemony,

or, at least, a recognition of the importance of smaller languages

in the lives of people. It is, at least, an excellent example of

how to defuse an issue often touted as potentially explosive—the

rights of linguistic minorities. European

nation states are now so well grounded in their respective national

languages that we often overlook what a vibrant history many non-standard

languages —"dialects"— have. Perhaps the recent (1976)

granting of linguistic autonomy in Spain to three minority languages

—Galician, Catalonian, and Basque— is a sign of some

sort of backlash in Europe against overbearing language hegemony,

or, at least, a recognition of the importance of smaller languages

in the lives of people. It is, at least, an excellent example of

how to defuse an issue often touted as potentially explosive—the

rights of linguistic minorities.

The

language of Naples—officially, of course—is Italian.

It's what newscasters speak, it's the language of the print media

and it's what kids learn in school. It is the national language

of Italy because of its glorious literary tradition going back to

the language of Dante and Boccaccio in 1300. It is the official

language of Naples because southern Italy was made part of the rest

of Italy by a series of wars in the 19th century, generally called

"The Wars of Unification" in history books. The spoken language

of most of the people in Naples, however, is the Neapolitan

dialect, that southern brand of Latin vernacular with as long a

history as the northern Tuscan vernacular upon which the national

language is based.

[For

a

separate item on the Neapolitan language]

In the

group of southern Italian literary figures since the Middle Ages who

have expressed themselves in their native, southern language, one of

the most important is Giambattista Basile, the author of Il Pentamerone

or Li Cunto de li Cunti (The Tale of Tales), known in English

as, simply, The Pentameron. It is the first published collection

of European fairy tales. It is a frame-story like Chaucer's Canterbury

Tales and Boccaccio's Decameron; that is, the telling of

tales is presented within the framework of a group of people passing

the time by sharing stories. Basile's Pentamerone tells fifty

tales over five nights, all of them in Neapolitan. The most famous of

the tales is Zezolla, also known as "The Cat Cinderella,"

apparently the first published version of the famous fairy-tale, better

known to English-language readers in a translation of the later French

version by Perault.

Basile

was born in Naples and lived and wrote there. He also traveled to and

wrote in Venice and Mantua, but always returned to Naples, where he

was the court poet for various families of the nobility, including that

of Stigliano Carafa. By 1620 he was among the most respected Neapolitan

writers, known for both madrigals and odes in Italian as well as poetry

in Neapolitan.

A

German-language edition of The Pentameron

It is, however,

for The Pentameron that he is remembered. It is a valuable source

for those who today study such things as comparative folk-tales in an

attempt to pin down themes that crop up almost universally across cultures.

At the time of Basile's death in 1632, no such lofty ambitions engaged

most people, least of all Basile's sister, who put the collection of

fairy tales on the back shelf somewhere while she tried to get her brother's

other works in Italian some posthumous attention. Fortunately, that

back shelf was on the premises of a local book-shop, the proprietor

of which had a great love for literature in the vernacular; within a

couple of years, the first few Neapolitan tales were published and by

1644 a complete version was published. It is, however,

for The Pentameron that he is remembered. It is a valuable source

for those who today study such things as comparative folk-tales in an

attempt to pin down themes that crop up almost universally across cultures.

At the time of Basile's death in 1632, no such lofty ambitions engaged

most people, least of all Basile's sister, who put the collection of

fairy tales on the back shelf somewhere while she tried to get her brother's

other works in Italian some posthumous attention. Fortunately, that

back shelf was on the premises of a local book-shop, the proprietor

of which had a great love for literature in the vernacular; within a

couple of years, the first few Neapolitan tales were published and by

1644 a complete version was published.

The

Pentameron was relatively late in finding a broader audience through

translation, almost certainly because of the linguistic difficulties

of the original version. Translators often worked from fragmentary French

versions done in the 1700s. Complete versions in German and English

did not appear until the early 1800s. Interestingly, a complete translation

with scholarly notes in Italian (the original Neapolitan is hopelessly

foreign to those in northern Italy) did not appear until 1920s when

Benedetto Croce turned his attention to it. "The Cat Cinderella" tale

in The Pentameron has gained more recent acclaim through the

efforts of Neapolitan musicologist, Roberto De Simone, whose staged

version of the tale has appeared throughout Europe in various languages.

One might

ask, Why would a poet who wrote odes and madrigals in Italian be fascinated

enough by dialect fairy-tales to devote so much of his life to collecting

them and writing them down? Not that everything needs to be explained,

but at least one version says that Basile was more than a little uncomfortable

with the opulence of the Baroque. He worked at the noble courts of Naples

in the early 1600s —a time and place when the rich were very rich

and the poor very poor. He had the reputation of being a modest

person who went out of his way to be honest and to avoid displays of

whatever wealth he possessed. Maybe, too, he was just fascinated by

tales in which simplicity is a virtue, ones in which good is rewarded

and evil punished. Or, maybe, he just liked a good story, like the rest

of us:

| There

was in that land an enchanted Prince so attracted by Nella's beauty

that he married her in secret. And in order that they might

see one another without arousing the suspicion of her wicked mother,

the Prince crafted a crystal passage from the royal palace directly

to Nella's abode, although it was many miles distant. Then he

gave her a magic powder saying, "Whenever you wish to see me,

throw a little of this powder into the fire, and I will come to

you instantly through this passage, as quick as a bird, along

the crystal road to gaze upon this face of silver.

—from

"The Three Sisters" in The Pentameron by Giambattista

Basile

|

That's

hard to beat.

Odessa

(ship)

This ship docked at the port of Naples

had become somewhat of a landmark, but it was becoming rustier and less

seaworthy with each passing month and year that it sat there. The Odessa

was built in 1970-74 in Newcastle, UK. She was 136 meters long, did

19 knots and carried 550 passengers and 265 crew. The Odessa

was once the proud flagship of the Soviet cruise fleet, and, indeed,

I remember it coming into Naples on a number of occasions in the 1980s.

At the time, Soviet tourists were an oddity in Naples. One time I went

down to the port to meet Viktor, a trombone-player friend of mine on

tour with the then Leningrad (now, St. Petersburg) Philharmonic. He

walked up smiling and wearing a watch on each wrist. He had been waylaid

by a dockside vendor, but he seemed content—and I'm sure the vendor

was. (I heard later that both watches gave up the ghost halfway through

the second movement of Shostakovitch's 5th symphony later that evening.)

Anyway, Viktor had arrived on the good ship Odessa. This ship docked at the port of Naples

had become somewhat of a landmark, but it was becoming rustier and less

seaworthy with each passing month and year that it sat there. The Odessa

was built in 1970-74 in Newcastle, UK. She was 136 meters long, did

19 knots and carried 550 passengers and 265 crew. The Odessa

was once the proud flagship of the Soviet cruise fleet, and, indeed,

I remember it coming into Naples on a number of occasions in the 1980s.

At the time, Soviet tourists were an oddity in Naples. One time I went

down to the port to meet Viktor, a trombone-player friend of mine on

tour with the then Leningrad (now, St. Petersburg) Philharmonic. He

walked up smiling and wearing a watch on each wrist. He had been waylaid

by a dockside vendor, but he seemed content—and I'm sure the vendor

was. (I heard later that both watches gave up the ghost halfway through

the second movement of Shostakovitch's 5th symphony later that evening.)

Anyway, Viktor had arrived on the good ship Odessa.

Then, time

passed, and suddenly—or so it seemed—the Odessa was

just there all the time in the port. A few weeks ago, I ferried

out of the port on my way to Sorrento, looked over at the usual place

and she was gone. As it turned out, the ship had stayed for seven years;

I had just lost track of the time.

When the

Soviet Union broke up, 200 ships were taken over by the Black Sea Shipping

Company (BLASCO) operating out of the port of Odessa in the Ukraine.

By the spring of 1995, Blasco owed 300 million dollars to its creditors

and was so far in debt that 24 of the company's ships were seized in

ports around the world. At the demand of a German creditor, the Odessa

was "arrested" (the term used in Admiralty law) on a cruise at Capri.

There were 360 passengers on board at the time. They disembarked in

Naples, and the ship was forbidden to set sail. (In such cases, port

authorities carrying out the "arrest," physically board the ship and

place a lock and chain around the wheel and post a warrant.)

The war

of attrition between the creditors and the skeleton crew left on board,

commanded by Captain Vladimir Lobanov, began. The Captain retained a

sense of humor throughout the affair, at one point telling reporters

that the crew was doing much better "now that all the rats have starved

to death". Most of the crew left, but the nine crew members who stayed

had a claim against the vessel and decided to tough it out in the hopes

of some day not having to return home totally penniless from the ordeal.

As in the cases of some of the Odessa's sister ships in

ports around the world, the plight of the crew attracted the sympathy

and solidarity of port workers, who took them food. In 1999, one of

the crew died in his cabin of a heart attack.

I now read

that the Odessa was auctioned off in April of 2002 for 1,250,000

euros, 500,000 euros of which was designated for the eight surviving

crew members. I read that the Odessa is again in its home port

on the Black Sea undergoing refitting for another try at the cruise

game.

Castles,

old

(This

ruin is high above the town of Pimonte at the beginning of the Sorrentine

peninsula.) (This

ruin is high above the town of Pimonte at the beginning of the Sorrentine

peninsula.)

Just another

old castle? Well, yes and no. Yes, the area around Naples—like

much of Europe—is dotted with ruins of medieval castles,

some of which have been fixed up for you to see, but most of which are

in various states of disrepair. The latter are the kind you are likely

to dismiss as "just another castle" as you whiz by them on modern highways. No,

on the other hand, if you realize that at the time they were built,

these castles served specific purposes and were manifestations of long

and complicated historical processes: the fall of Rome, the struggle

between Byzantium and the West for control of Italy, the birth of the

Holy Roman Empire, the beginnings of feudalism, etc.

Thus, stepping

back and taking a closer look at some of these structures near Naples—those

restored as well as those in ruins—gives some insight into

a period often glossed over as the "Middle Ages." The gloss covers chivalry,

chicanery, knights, codpieces, maidens and castles, but often skips

the events that have shaped modern Europe.

There are

a number of such castles as you drive east out of Naples on the autostrada

approaching the Sorrentine peninsula and again on the peninsular road

itself. First, on the left as you approach the Salerno-Sorrento junction

is the castle of Lettere. The castle and the town of Lettere are perched

at 400 meters on the western slope of the Lattari mountain range, the

backbone of the Sorrentine peninsula that then joins the main Apennine

range further east. The turrets and ramparts of the old castle are still

quite discernible from the road. It is not exactly a falling-down ruin;

i.e. at least the outer shell is still intact. However, the castle cannot

be entered easily—or entirely safely, for that matter.

The interior is overgrown and pretty much in shambles. It looks restorable,

however, and they talk about that all the time, since it is, at

least potentially, a tourist attraction. It was built in the 9th

century on the site of an older Roman fort on that strategic height,

a fortress that at times hosted no less than Roman dictator Sulla as

well as later emperors. (There has been scaffolding on the outer walls

for a number of months, so maybe a restored castle is in the offing.)

| This

print by 18th-century artist, J.L. Phillipe Coignet, shows Vesuvius

as seen from the ruins of the old Castellammare ("Castle on the

sea"). |

Moving

out onto the peninsula, you pass through two tunnels and then down the

road onto the coast. On that road is a fine and solid, new-looking

castle on your right as you drive out. It is in such good shape—clearly

lived in—that it belies its age. This is the castle of

Castellammare di Stabia; that is, the castle that the city of

Castellammare ("Castle on the Sea") was named for. It is at the base

of the ridge below Monte Faito. The modern town below the castle sits

on Greek, Etruscan, Samnite and Roman ruins, the Romans being the ones

who gave the name Stabia to the site. The castle has been rebuilt

many times over the centuries, the last time in 1956 to make it habitable.

It is first mentioned in the 1000s as having been built at the behest

of the Duke of Salerno (of which more, below). Also, not visible at

all from the road, but there nonetheless, are a few smaller structures

well up on the hillside, such as the castle of Pino at 500 meters above

sea level. It is accessible from the road that passes over the mountain

from Castellammare to Agerola. And there are other smaller ruins scattered

along the western side of the Lattari range. Moving

out onto the peninsula, you pass through two tunnels and then down the

road onto the coast. On that road is a fine and solid, new-looking

castle on your right as you drive out. It is in such good shape—clearly

lived in—that it belies its age. This is the castle of

Castellammare di Stabia; that is, the castle that the city of

Castellammare ("Castle on the Sea") was named for. It is at the base

of the ridge below Monte Faito. The modern town below the castle sits

on Greek, Etruscan, Samnite and Roman ruins, the Romans being the ones

who gave the name Stabia to the site. The castle has been rebuilt

many times over the centuries, the last time in 1956 to make it habitable.

It is first mentioned in the 1000s as having been built at the behest

of the Duke of Salerno (of which more, below). Also, not visible at

all from the road, but there nonetheless, are a few smaller structures

well up on the hillside, such as the castle of Pino at 500 meters above

sea level. It is accessible from the road that passes over the mountain

from Castellammare to Agerola. And there are other smaller ruins scattered

along the western side of the Lattari range.

Many of

these castles have a common link. In 774 Charlemagne entered Rome, and,

in so doing, took over Lombard holdings in northern Italy and,

as well, established his authority over the new Vatican States of central

Italy. Thus ended the 200-year Lombard kingdom that had ruled

most of Italy since shortly after the fall of the Roman Empire. Then,

in 800 Charlemagne had himself crowned with the very crown of the Lombard

kings, proclaiming the end of one kingdom and the beginning of another,

the Holy Roman Empire.

This description

leaves out an important item, one that is crucial to understanding the

next 1000 years of Italian history: Charlemagne didn't get the job done.

He failed in his Justinian-like quest to reunite Italy. Charlemagne

spent much of the late 700s fighting Saxons and Moors elsewhere, but

in Italy he was content to leave the southern half of the peninsula

still solidly in the hands of the Lombards. Left to its own devices,

southern Italy became the large Lombard Duchy of Benevento. It was not

a monolithic political unit, but the Lombards had always been loose-knit

in Italy, anyway, governing as more of a confederation than a single

state. Starting in the early 800s, then, from south of Rome all the

way down the peninsula, and centering on the town of Benevento, the

Lombards continued to hold sway in the south. Thus began the division

of Italy into north and south, a division that would not be healed until

1860.

The castles

mentioned in this article came into being directly because of events

in the mid-800s. The Duchy of Benevento underwent a civil war in the

830s. The war was ended by a treaty in 839 that established a separate

Duchy of Salerno. This left the Sorrentine peninsula and the area

above the Sarno valley in a volatile state. Three duchies were

now contiguous: the independent Duchy of Naples, the still vast (in

spite of the civil war) Duchy of Benevento, and the new Duchy of Salerno.

They all came together in these mountains. Salerno,

to keep her neighbors honest, started building forts on the western

slopes to keep both Naples and Benevento at bay. Both the castle of

Lettere and the one at Castellammare are from that period, as are the

smaller ones mentioned above.

The castles

did their job until the coming of the Normans in the 11th century. Coming up the boot

from their newly-founded Kingdom of Sicily, they fused Southern Italy

into a single unit, beginning the modern Kingdom of Naples that would

last until 1860. The various castles that had helped cement in place

the fragmentation of the south into smaller units passed into the hands

of feudal landlords—the dukes and barons—who

then ruled their smaller fiefdoms while pledging loyalty to the king

of Naples. Many of the structures were of strategic, military importance

well past the "age of castles". They served into the 16th and even 17th

century and were important in protecting the coastal areas of Naples

from marauding bands of Saracens, Moslem pirates who plagued southern

Italy for many centuries.

Pontano Chapel

The Pontano Chapel is the small grey building at the

western end of Via Tribunali in the historic center of the city (#37

on the map of the historic center). The perfect classic Roman

design is attributed to Giocondo da Verona and was built in 1492 by

Giovanni Pontano to be a family chapel. The Pontano Chapel is the small grey building at the

western end of Via Tribunali in the historic center of the city (#37

on the map of the historic center). The perfect classic Roman

design is attributed to Giocondo da Verona and was built in 1492 by

Giovanni Pontano to be a family chapel.

Pontano

(1426-1503) was the most celebrated Neapolitan humanist of the day,

a friend of the sovereign of Naples, Alphonso the Magnanimous, and,

indeed, tutor of the king's sons. He was important as a diplomat for

the Aragonese in Naples, but his claim upon history is as a poet and

scholar. Pontano is often referred to as the last great poet in the

Latin language. He founded in Naples what was called "The Academy"

—a meeting place for the erudite. The Academy was

influential among men of letters not only in the Kingdom of Naples,

but elsewhere in Italy. Subsequently it became known as the Pontanian

Academy, and its influence lasted well beyond the lifetime of the founder.

Belfry, oldest

Adjacent

to that chapel is the church of S. Maria Maggiore della Pietrasanta.

It was built in 533 and is one of the paleo-Christian churches in Naples. Its origins involve

one of the weirdest tales of ancient Naples. In 533, the Virgin Mary

is said to have appeared to Bishop Pomponius of Naples and commanded

him to chase away a swine possessed of the devil that had been frightening

citizens of the area. He did and then built and consecrated this church

on the site of an earlier temple dedicated to Diana. The church was

considered one of the most impressive examples of early Christian architecture.

The relatively modern appearance of the church is due to the reconstruction

of 1653.The remarkable red-brick belfry (photo, right) on the grounds

is the oldest free-standing tower of its kind in Naples. It was part

of the original church complex, though built later (c. 900 a.d.). The

base of the tower (upper photo) incorporates earlier Roman bits and

pieces as contruction material, some of which are said to be part of

the earlier temple.

San

Gennaro (1)

'Ha

fatto il miracolo?' 'Did

he perform the miracle?'

| Statue

of S. Gennaro at the entrance to the port of Naples |

Neapolitans

have asked themselves that question any number of times throughout their

history. A few days after Giuseppe Garibaldi

entered Naples (thus ending the 800-year history of the Kingdom of Two

Sicilies and creating modern Italy in the process), San Gennaro (St.

Januarius), the patron saint of the city, indeed, performed the wonder

right on schedule. Solid remnants of the martyred saint's blood, contained

in a vial in the Cathedral of Naples,

miraculously and mysteriously liquefied on September 19, 1860, and,

thus conferred, according to popular belief, divine benediction on Garibaldi's

victory. Neapolitans

have asked themselves that question any number of times throughout their

history. A few days after Giuseppe Garibaldi

entered Naples (thus ending the 800-year history of the Kingdom of Two

Sicilies and creating modern Italy in the process), San Gennaro (St.

Januarius), the patron saint of the city, indeed, performed the wonder

right on schedule. Solid remnants of the martyred saint's blood, contained

in a vial in the Cathedral of Naples,

miraculously and mysteriously liquefied on September 19, 1860, and,

thus conferred, according to popular belief, divine benediction on Garibaldi's

victory.

On the

other hand, there is a story they tell from the days of the Neapolitan

(or Parthenopean) Republic, the sister Republic of revolutionary

France, and one that lasted a mere five months in 1799. On the first

Sunday in May, the other time when the miracle is said to occur, it

didn't. This provoked the French commander—desperate to win popular

support for his troops occupying the city— into the interesting

move of threatening to kill the Archbishop of Naples if the sign from

Heaven were not forthcoming. A short while later it came forth, thus

lending, at least in the mind of the French general— and notwithstanding

skeptical popular charges of pseudo-divine hanky-panky—

credence to his claim that God was on the side of the Revolution.

(Interestingly, this led to the temporary displacement of Gennaro as

the patron saint of Naples in the hearts of loyalist Neapolitans. There

are a number of paintings showing St. Anthony at the head of the army

of the Holy Faith, the Sanfedisti, as they enter the city

to retake it from revolutionaries in 1799. The illustration on the right

shows "the princes returning to Naples" under the watchful protection

of St. Anthony and not San Gennaro.)

San Gennaro

was the Bishop of Benevento and was beheaded at Pozzuoli in 304 during

Diocletian's persecution of the Christians. They had to chop his head

off, the story goes, because when they had thrown him to the lions once

before, the animals had refused to attack him and had simply crouched

in submission at his feet. His remains were taken to Napoli to be conserved.

The "miracle of San Gennaro," then, refers to the liquification of the

clotted blood of the saint. It is said to happen two times a year at

the Duomo (Cathedral) of Naples and at the Church of San Gennaro

at Solfatara in Pozzuoli, virtually on the spot where he was killed.

September 19 is the anniversary of his martyrdom. It is, thus, the saint's

name-day, as well, and Gennaro is the most common name given

to male babies born in Naples. Besides September 19 and the first Sunday

in May, some sources say the miracle may also occur on December 16,

in commeration of a violent explosion of Vesuvius, which spared the

city in the 1600s.

The granting

or withholding of the miracle by the saint is, in the minds of many

believers, intimately connected with the fortunes of the city--a prediction,

perhaps, of traumatic occurences such as war, pestilence and natural

calamity, or even something not so earthshaking, such as whether or

not Napoli will win the football championship. It might also

be a general notice of solidarity or disapproval from on high, as in

the cases noted above. The official position of the Roman Catholic Church,

which can, if it desires, make a pronouncement, on the validity of claims

of miraculous occurences, is one of neutrality. Of course, in this our

21st-century Age of Skepticism, one expects to find skeptics, even among

otherwise faithful, practicing Roman Catholic Neapolitans. But just

as Christian scriptures remind us that we do "not live by bread alone,"

there are those who would remind us that the same goes for a people

and a city; they couldn't have survived as long as they have without

a little help. If you are out and around on one of the dates when "it"

is supposed to happen, keep an eye on the reactions of those around

you. Notice how even the skeptics cannot conceal their relief upon hearing

that "San Gennaro ha fatto il miracolo!"

[If

you want to read Mark Twain's less benevolent view of the miracle of

San Gennaro, click here.]

|

This ship docked at the port of Naples

had become somewhat of a landmark, but it was becoming rustier and less

seaworthy with each passing month and year that it sat there. The Odessa

was built in 1970-74 in Newcastle, UK. She was 136 meters long, did

19 knots and carried 550 passengers and 265 crew. The Odessa

was once the proud flagship of the Soviet cruise fleet, and, indeed,

I remember it coming into Naples on a number of occasions in the 1980s.

At the time, Soviet tourists were an oddity in Naples. One time I went

down to the port to meet Viktor, a trombone-player friend of mine on

tour with the then Leningrad (now, St. Petersburg) Philharmonic. He

walked up smiling and wearing a watch on each wrist. He had been waylaid

by a dockside vendor, but he seemed content—and I'm sure the vendor

was. (I heard later that both watches gave up the ghost halfway through

the second movement of Shostakovitch's 5th symphony later that evening.)

Anyway, Viktor had arrived on the good ship Odessa.

(This

ruin is high above the town of Pimonte at the beginning of the Sorrentine

peninsula.)

(This

ruin is high above the town of Pimonte at the beginning of the Sorrentine

peninsula.) Moving

out onto the peninsula, you pass through two tunnels and then down the

road onto the coast. On that road is a fine and solid, new-looking

castle on your right as you drive out. It is in such good shape—clearly

lived in—that it belies its age. This is the castle of

Castellammare di Stabia; that is, the castle that the city of

Castellammare ("Castle on the Sea") was named for. It is at the base

of the ridge below Monte Faito. The modern town below the castle sits

on Greek, Etruscan, Samnite and Roman ruins, the Romans being the ones

who gave the name Stabia to the site. The castle has been rebuilt

many times over the centuries, the last time in 1956 to make it habitable.

It is first mentioned in the 1000s as having been built at the behest

of the Duke of Salerno (of which more, below). Also, not visible at

all from the road, but there nonetheless, are a few smaller structures

well up on the hillside, such as the castle of Pino at 500 meters above

sea level. It is accessible from the road that passes over the mountain

from Castellammare to Agerola. And there are other smaller ruins scattered

along the western side of the Lattari range.

The Pontano Chapel is the small grey building at the

western end of Via Tribunali in the historic center of the city (#37

on the map of the historic center). The perfect classic Roman

design is attributed to Giocondo da Verona and was built in 1492 by

Giovanni Pontano to be a family chapel.

The Pontano Chapel is the small grey building at the

western end of Via Tribunali in the historic center of the city (#37

on the map of the historic center). The perfect classic Roman

design is attributed to Giocondo da Verona and was built in 1492 by